Frank Canton found his work cut out for him when he headed to Circle City to serve as the first lawman in Interior Alaska.

LAW AND ORDER

ALASKA’S FIRST LAWMEN

Alaska’s first law officer in the Interior knew a thing or two about the criminal element. Frank Canton, appointed deputy marshal for Circle City in February 1898, had served with distinction as a peace officer in Wyoming and Oklahoma Territory. He’d also escaped from prison while serving time for a litany of offenses.

The sketchy lawman’s reputation as a range detective in Wyoming, notably as a killer who ambushed rustlers, secured his appointment in Alaska because he’d come to the attention of one very influential man, according to Gerald O. Williams in the Alaska State Troopers’ “50 Years of History.”

Frank Canton found his work cut out for him when he headed to Circle City to serve as the first lawman in Interior Alaska.

Portus B. Weare, a leading shareholder of the North American Transportation and Trading Company, which was challenging the monopoly of the Alaska Commercial Company, felt his business needed the protection of a vigorous law enforcement officer. Weare agreed to supplement Canton’s $750 a year salary.

On his way to his new post, weather forced Canton to spend the winter in Rampart in 1898. He tried his hand at prospecting but put his peace officer hat back on in April after passengers onboard a steamboat wintering near Rampart mutinied against their captain. They announced their intention to take the steamboat to Dawson as soon as the waterway opened.

After a two-day hike, Canton reached the vessel and arrested the leaders of the conspiracy. He then convened a meeting of the other passengers, and serving as judge, held a trial and fined the perpetrators $2,000.

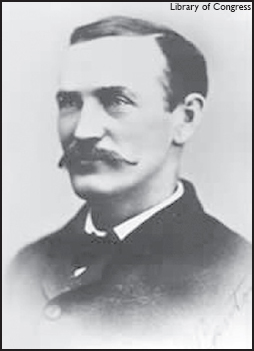

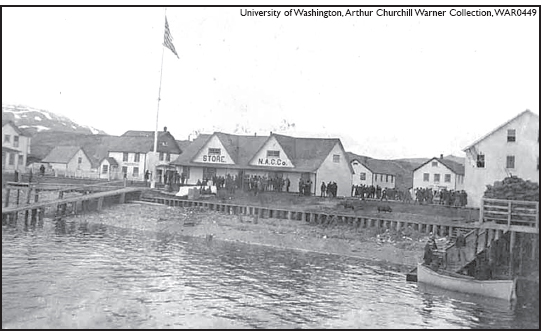

Frank Canton arrived in Circle City, at one time a hub of gold-rush activity, in 1899. At the right, the sternwheeler Yukon is tied up to the bank of the Yukon River.

When one of the takeover leaders attempted to kill him, Canton recognized him as a fugitive from Idaho with a $2,500 bounty on his head. Canton arrested him, and as soon as the ice went out on the Yukon River, he hauled the fellow to Circle City.

By the time he reached his new post, Canton found that most of the miners had moved on to Dawson. Their exodus meant that city coffers were limited, so the lawman had no funds with which to operate. He also found that no one in the community wanted to board federal prisoners for $3 a day, nor act as jailers.

Canton had to borrow money from the Northwest Trading Company to meet the obligations of his office. Shortly thereafter, he wrote to U.S. Marshal James Shoup in Sitka requesting money to meet daily expenses and to construct a jail.

Before he heard back from Shoup, Canton had several more suspects accused of robbery and attempted murder in custody. The small U. S. Army garrison at Circle helped him guard his prisoners while he awaited funds.

To his dismay, the reply he received in March 1899 didn’t include money for running the marshal’s office or any reimbursement for out-of-pocket expenses. Canton wrote an angry letter back to the U.S. marshal.

“I need some money very bad and wish you would send in some funds at once,” he ranted. By that time, Canton had eight prisoners he intended to take to Sitka for trial.

Canton never received funds from Shoup. Instead, he was discharged as a deputy marshal when officials learned he had resigned his Oklahoma position while being audited for fraudulent expense claims. The Justice Department hadn’t been aware that Canton had been appointed a deputy marshal in Alaska until late 1898.

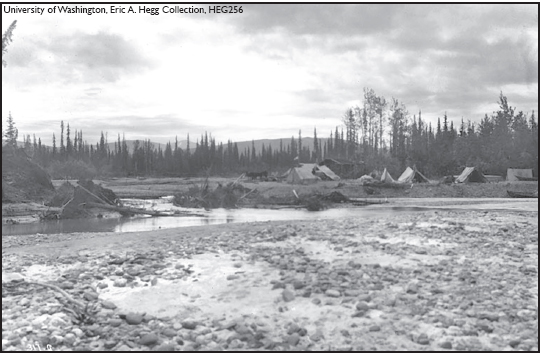

Frank Canton spent his first winter in Alaska near Rampart.

Early lawmen in Alaska had to cover vast amounts of territory. These prospectors are camped near the Koyukuk River in 1899.

Camps popped up along creeks throughout Alaska during the gold-rush era, including at the mouth of Slate Creek, shown here, around the Koyukuk in 1898.

The discharged officer returned to Oklahoma and became deputy marshal for Judge Isaac Parker. In 1907 he became adjutant general of the Oklahoma National Guard, serving until he died in 1927. Following his death, it was revealed that his real name was Joe Horner, a wanted outlaw, murderer and bank robber who started out as a badman in Texas and later changed his name.

Harry Sinclair Drago, who wrote “The Great Range Wars: Violence on the Grasslands,” summed up Canton: “Frank Canton was a merciless, congenital, emotionless killer. For pay, he murdered eight – very likely 10 men.”

Life wasn’t easy for Alaska’s early lawmen, which by the Klondike Gold Rush consisted of one judge, one marshal, 10 deputy marshals and 20 Native officers scattered in Southeast villages. While the lure of gold brought an abundant amount of unsavory characters north during the late 1800s, U.S. marshals didn’t have budgets to pursue, capture or hold evildoers who committed crimes in the territory.

Due to the logistics of covering such a large expanse of land, suspects sometimes roamed at large for months, perhaps years, before being taken into custody.

Once lawmen did capture their quarry, there was also the problem of transporting the prisoners to Sitka for trial. More often than not, the marshals were required to pay the cost of transportation for themselves and their prisoners and then submit invoices for possible reimbursement.

This sad situation didn’t escape the vigilant eye of the editor of the Sitka Alaskan in 1890:

“Under the Organic Act (of 1884) … the judicial officers of this vast territory are a (single) United States judge, a marshal, clerk of court, and United States attorney, all stationed at Sitka; a United States commissioner at Sitka, Juneau, Wrangell and Ounalaska (Unalaska). With this vast army of officers, crime was … to be wiped out in Alaska.”

“But something seems to be lacking,” the editor noted. “A murder is committed at Kodiak. A month or two later a sailing vessel arrives. The murder is reported, and on its return to San Francisco, word is sent to the deputy marshal at Ounalaska, also by sailing vessel, or possibly a revenue cutter or steamer of the Alaska Commercial Company, which makes semi-annual trips.

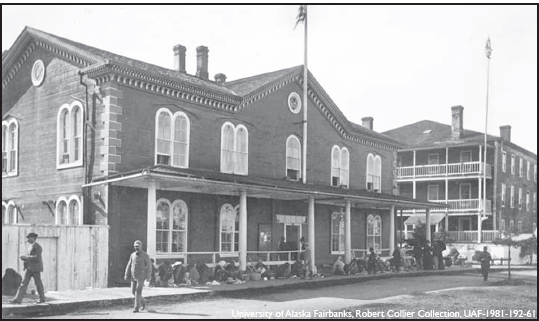

The two-story courthouse in Sitka, shown here in 1890, was the main center for trials in the territory at the turn-of-the-last century.

“He then reports to his chief in Sitka, via San Francisco, and if the vessels are not lost in the course of a year or so, he may get a warrant for the arrest of the malefactor. If he is in haste to arrest him, he will take the first vessel to San Francisco, thence to Kodiak – as this is the shortest and usually the only route between the ports.

“If he is lucky enough to find the man still alive, he will arrest him; and by this time the last vessel for the season having probably sailed, he and his prisoner will wait quietly another six months, when by schooner and steamer by way of San Francisco and Puget Sound, prisoner and marshal may arrive in Sitka to find that in the change of administration, the case (has been) forgotten, and the deputy marshal salted for all his expenses.”

A “floating court” of sorts evolved when justice was meted out from the decks of revenue cutters beginning in the late 1880s.

A commander in the U.S. Revenue Marine, precursor to the U.S. Coast Guard, was the first revenue cutter commander to make regular patrols into the harsh arctic waters. Capt. Michael A. Healy was about the only source of law in a lawless land, and he transported criminals onboard the cutter Bear from remote Alaska communities to Sitka for trial.

U.S. Revenue Marine Capt. Michael A. Healy poses with his pet parrot on the quarterdeck of his most famous command, the Revenue Cutter Bear, around 1895.

Healy began his 49-year sea career in 1854 at age 15 when he signed on as a cabin boy aboard the American East Indian clipper Jumna bound for Asia.

The son of a Georgia plantation owner and an African slave from Mali, Healy quickly became an expert seaman. During the Civil War, he requested and was granted a commission as a third lieutenant in the U. S. Revenue Marine from President Abraham Lincoln.

After serving successfully on several cutters in the East, Healy began his lengthy service in Alaska waters in 1875 as the second officer on the cutter Rush. He was given command of the revenue cutter Chandler in 1877. Promoted to captain in March 1883, he then assumed command of the cutter Thomas Corwin in 1884. Finally, in 1886, he became commanding officer of the Bear, taking her into Alaska waters for the first time.

He became a legend enforcing federal law along Alaska’s 20,000-mile coastline. In addition to befriending missionaries and scientists, he rescued whalers, Natives, shipwrecked sailors and destitute miners, according to the U.S. Coast Guard.

The captain often drove himself and his crew beyond the call of duty, as in 1888, when the Alaska whaling fleet was anchored behind the bar at Point Barrow to ride out a southwest gale.

The wind veered to the north, and huge waves broke over the bar. Four ships broke apart and sank, tossing the ships’ crews into the icy waters. Healy and the Bear’s crew saved 160 whalers, Coast Guard records show.

Healy also assisted in serving the humanitarian needs and welfare of Native Alaskans through the introduction of reindeer to Alaska in order to replace the declining whale and seal populations, which were among the Natives’ primary food sources.

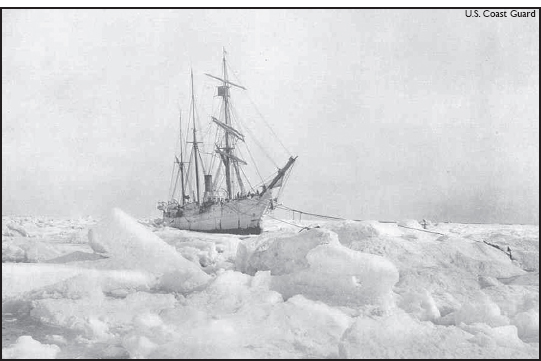

The Bear plied Arctic Ocean waters, often vying for a pathway through icebergs.

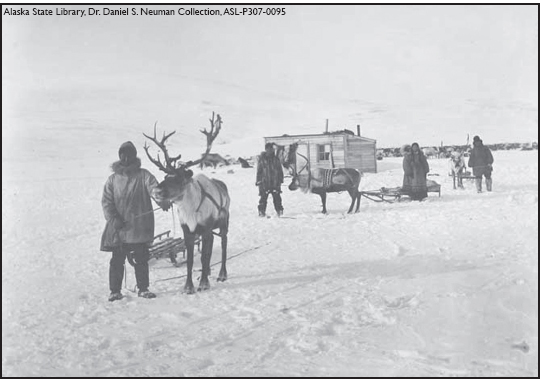

Several Eskimos lead harnessed reindeer at a camp in northern Alaska.

While serving as second-in-command of the Thomas Corwin as it searched for the lost exploration ship Jeanette along the Siberian Coast in 1881, he noticed that the Chukchi people were able to sustain themselves by raising reindeer. In 1890, Healy used that knowledge to work with the Rev. Dr. Sheldon Jackson and famous naturalist John Muir to import reindeer to Alaska.

At his own expense, Healy transported 16 reindeer from the Natives of the Siberian Coast to the Seward Peninsula. In 1892, another 171 reindeer were added to the herd and Teller Reindeer Station was established. More reindeer followed. These selfless acts and humanitarian efforts helped Natives continue their subsistence ways and probably saved many lives.

Coincidentally, his interpreter in the Arctic was Mary Makrikoff, who years later would become the first Native woman to own her own reindeer herd and be known as “Reindeer Mary” and “Sinrock Mary,” as told in “Aunt Phil’s Trunk: Volume 1.” During the early 1900s, she was the richest Native woman in Alaska, selling reindeer to prospectors, the government and others.

An article that appeared in the New York Sun in the 1890s reported that Healy was a mighty man:

“Captain Mike Healy is a great deal more distinguished person in the waters of the far northwest than any President of the United States … He stands for law and order in many thousands of miles of land and water, and if you should ask, ‘Who is the greatest man in America?’ the instant answer would be: ‘Why, Mike Healy.’”

But at the same time that Healy was being praised in some quarters, he was being denounced for his brutality in others.

Long voyages under harsh conditions often caused tempers to flare onboard vessels. And while captains had to run tight ships because breaches of discipline could mean the loss of the ship and crew, some seamen accused Healy of being downright cruel.

The San Francisco Coast Seamen’s Journal, dated Feb. 21, 1894, listed two incidents involving Healy in a report on “cases of cruelty perpetrated upon American seamen. …”

Pictured here in 1899, Ounalaska – now called Unalaska – was a port of call for the Revenue Cutter Bear.

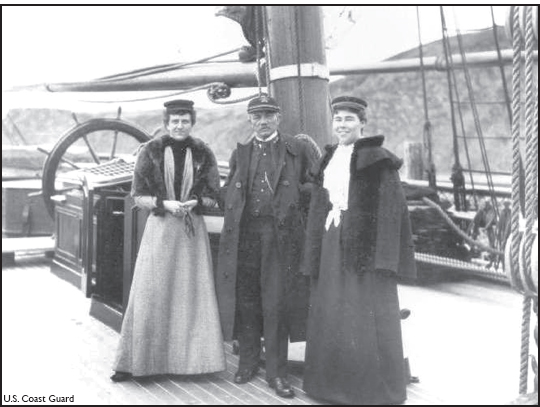

Capt. Michael A. Healy takes a moment to pose with two unidentified women onboard the Revenue Cutter Bear.

“Three seamen, Holben, Daweritz and Frandsen, of the American bark Estrella charged that while discharging coal into the Bear in the harbor of Ounalaska in June 1889, Captain Healy, without provocation, ordered them placed in irons and confined in the forepeak of the Bear. Then they were triced up with their hands behind them and their toes barely touching the deck. The punishment lasted 15 minutes and the pain was most excruciating. They were then tied with their backs to the stanchions and their arms around them for 42 hours. They were then put ashore and made to shift for themselves. The seamen accused both Captain Healy and Captain Avery of the Estrella of drunkenness and gross incapacity; …”

The U.S. Department of the Navy exonerated Healy.

The second report came from the crew of whaling bark Northern Light for an incident on June 8, 1889, involving cruelty from the officers.

“Captain Healy ordered them all in irons. First Lieutenant of the Bear was sent aboard the Northern Light to execute the order. Crew triced up to the skids with arms behind their backs and toes just touching the deck. One man’s hands were lashed with hambroline (small cord), as the irons were too small for his wrists; line cut into the flesh three-eights of an inch. One man fainted from pain and the Bear’s doctor had to bring him to. Men were triced up 15 minutes, suffering untold pain.”

Healy was sidelined for four years following his controversial court-martial conviction for “gross irresponsibility” and “scandalous conduct,” even though “tricing” was a legal means of punishment at the time. But when the 1900 Alaska gold rush called for more cutters, Healy was given command of the cutter McCulloch and went north again. He spent his last two years of service on Alaska waters aboard the cutter Thetis. He retired in 1904 at the mandatory retirement age of 64 and died one year later.

For his service to his country, the Alaska Native people and to their way of life, Healy was honored by Congress, the whaling industry, missionary groups and civic organizations on both the Atlantic and Pacific coasts. He earned the nickname “Hell Roaring Mike” for his forceful leadership and determination to succeed in all missions, whether military or humanitarian, and some say for his actions when under the influence of alcohol.

The 420-foot U.S. Coast Guard Cutter Healy, the largest cutter and polar icebreaker in the Coast Guard fleet, was named in his honor and put into service in November 1999.

Another bigger-than-life member of law enforcement also made his mark on the Great Land – through wise deliberations, politics and perseverance.