Judge James Wickersham set up Alaska’s first official traveling court in the laundry building in Valdez in 1900.

JUDGE’S LIGHT SHINES ON

While Capt. Michael A. Healy was instrumental in carrying out justice in Alaska waters and villages, Judge James Wickersham finally initiated a more formal traveling judicial system at the turn-of-the-last century.

His system evolved after he sailed to Unalaska in 1900 to preside over the first felony trial on the Aleutian Chain. Recognizing that Unalaska’s small population wouldn’t allow him to summon sufficient jurors, he took more than a dozen people with him to Valdez and set up court in a building housing the town’s laundry. That first trial led to the establishment of an official traveling court.

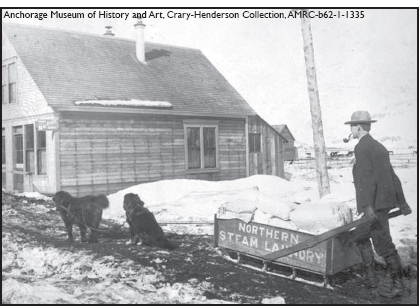

Judge James Wickersham set up Alaska’s first official traveling court in the laundry building in Valdez in 1900.

This photograph shows a man delivering a load of laundry to the Northern Steam Laundry via dog sled.

Born in Patoka, Illinois, Wickersham emigrated west, landing in Washington Territory in 1883 where he became attorney for the city of Tacoma. While in that capacity, he won a $1 million lawsuit concerning Tacoma’s water system. Tacoma acquired both the water and light systems in the settlement and thus started the first municipal light and water utilities in the West.

It was said, jokingly, in the Northwest that Wickersham was sent to Alaska to get him out of Washington politics. If so, Washington tossed a whole hornet’s nest into Alaska, for he was the storm center of more controversies and is credited with having written and made more history than any other of Alaska’s early public figures.

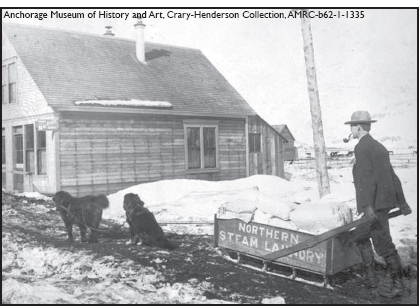

Judge James Wickersham, surrounded by law books, sits at his desk in the Interior.

Wickersham wrote in his book, “Old Yukon,” that those who were active in urging his appointment to a distant post were those attorneys and representatives of certain public utilities against whom he had battled in support of the public interest. However, when he was offered a post as district judge of the newly organized Third Judicial Division of Alaska, he enthusiastically embraced the opportunity to help found “American Courts of Justice in the northern territory.”

Wickersham was called upon to travel to Nome to clear up disputed mining claims during the famous Noyes-McKenzie affair, written about in Rex Beach’s “The Spoilers.” It seems a federal judge and several other men worked a bit of claim jumping through the legal system, so Wickersham faced a slew of unresolved cases when he arrived during the fall of 1901.

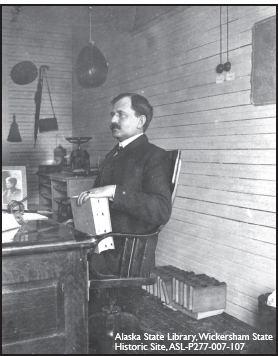

Once gold was discovered on Anvil Creek in Nome in 1898, pictured above, prospectors flocked to the Seward Peninsula in hopes of striking it rich. And when they found the best claims already taken, some made plans to make those claims their own.

It all started following the discovery of gold on Anvil Creek in 1898 by the “Three Lucky Swedes.” When news of the strike hit the Klondikers late the next spring, 8,000 people left Dawson for the coast in a single week. But the prospectors flooding to Nome found all the best claims already staked and were unhappy that foreigners had grabbed the most valuable claims.

In an effort to drive out the Swedes and their friends, a group of prospectors gathered on July 10, 1899, for a public meeting to pass a resolution that the foreigners’ claims were unlawful and that the area of Anvil Creek would be open to claims again.

It’s reported that some accomplices set up large bonfires on the beach to light as soon as the resolution was passed. The fires would signal others stationed on the mountains above the beach that they could take over the Scandinavians’ claims.

But before the men could carry on with their plan, a military troop from St. Michael interrupted the gathering and a Lieutenant Spaulding declared the meeting over.

That same month, gold was discovered on Nome’s beaches. A judge ruled that the beach could not be staked, so more than 2,000 people camped along 30 miles of beach and mined the sand 24 hours a day with gold pans, rockers and sluice boxes.

But while the disgruntled stampeders were somewhat mollified by the gold in the sands of Nome, others in high political offices made their own plans to appropriate the gold fields staked by the Scandinavians.

When Alexander McKenzie, an influential Republican, arranged to have President William McKinley appoint Alfred N. Noyes as judge of one of the three newly created judicial districts in Alaska, the stage was set to separate hardworking miners from their claims.

Noyes, along with his friend, McKenzie, arrived in Nome in July 1900 to begin their high jinks. That the judge was McKenzie’s henchman would soon become apparent. The two men set up a receivership racket and hired others to jump claims.

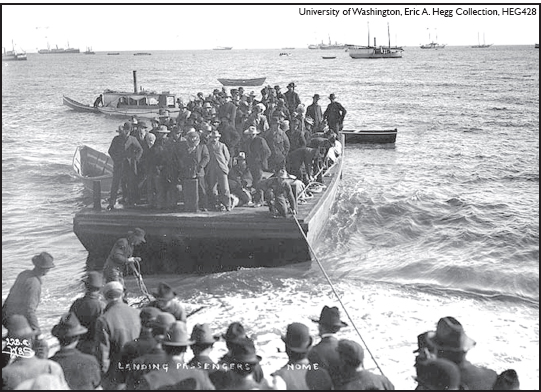

Scows brought eager prospectors from steamships to the beaches of Nome, where shady politicians and lawmen laid in wait to separate them from gold claims.

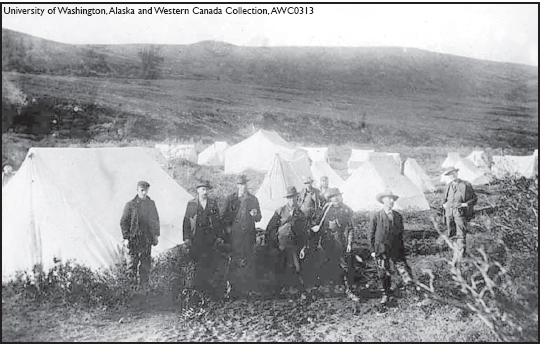

Judge James Wickersham had his work cut out for him when he arrived in Nome to clean up the mess left by Judge Alfred N. Noyes in 1901.

Pictured above is Nome’s City Hall, built in 1904.

One of the first legal proceedings the new judge enacted was to declare a row of the most valuable claims at Anvil Creek to be unlawful. The Scandinavians were not notified that their claims were the subject of a court action until McKenzie’s men showed up and chased them off.

When the legitimate claim owners appeared in court to have disputes settled, Judge Noyes put the claims into receiverships to be administered by McKenzie while the judge supposedly considered the disputes. In this interim, McKenzie hired men to mine the claims and commandeer all assets, including gold already extracted.

Noyes denied the Scandinavians the right to take their cases to a higher court, but a lawyer for legitimate claim owner Charles Lane of the Wild Goose Company finally took his case to the circuit court of appeals in San Francisco and won.

When Judge Noyes said he wasn’t subject to the new court and ignored the ruling, the Scandinavians lost patience. By use of force, the miners took back their claims.

Subsequently, U.S. marshals arrested McKenzie, who was sentenced to one-year imprisonment, and Noyes, who was removed from his position.

Excerpts from Judge Wickersham’s October 1901 diary entries hint at the problems he encountered when he arrived in Nome and how he meted out justice for all.

Oct. 5

“… Civil cases are crowding hard these days and I work in the office and courtroom from 9 a.m. to 10 and 11 p.m. The only way to clean up the business of this country is to push hard and I intend to clean it up before spring.”

Oct. 6

“Went down to see Mrs. Noyes off today – also called at her rooms. She is greatly distressed at the conditions which compel her to leave Nome under a cloud. She could not restrain her tears, and at the beach, when about to go aboard the lighter to go out to the vessel, she all but broke down. Mrs. Frost bears up much better – but it was a distressing ordeal for each of them.

“Six insane men sent out today on the Elihu Thomson, prisoners go later. Working today on opinion in Butler v. Good Enough Mining Co., an important mining case.

“I am satisfied that it will go hard with Judge Noyes, Dist. Atty. Woods, Frost, and possibly (ex-Congressman Thomas J.) Geary. McKenzie got six months on each of two charges, (Dudly) Du Bose six months and the facts against the others seem stronger.”

Oct. 29

“Have decided the case of Hemen v. Griffith, Rice, Wild Goose Co. and others, involving another Ophir Creek (mining) case. The attorneys now tell me that the case decided yesterday involved more than half a million dollars. I am pleased to know that mine owners now express a feeling of safety over property rights and do me the honor to say that investments can now be made here with assurance of fair protection.

“Judge Noyes seems never to have rendered even one mining opinion and but one mining case was tried by him in the more than a year that he was here. Yesterday I dismissed all the indictments in the now famous Glacier Creek riot cases.

“Judge Noyes left Nome on August 12, 1901, after signing the most contradictory and extraordinary batch of orders while out on the steamer – drunk, it is said by his enemies – certainly the orders were – and the result was a rising of people who went out to the richest mines on the Glacier Creek masked and armed and drove off all the “jumpers” and warned them to leave the country.

“They were arrested – at least half a dozen men who were supposed to be among the “rioters” were indicted and Griffin and Till Price have been tried. The jury in each case disagreed – so much prejudice exists against the Noyes-Stevens regime that it is impossible to convict these men for a violation of their injunctions or a contempt of their court – they ought not to be severely dealt with because the conditions were such as to drive good citizens to acts of lawlessness.

Three men, two children and a dog stand around “Wickersham Headquarters” sign displayed on the front of Lomen Brothers store in Nome.

“So after the failure to convict the first two I felt justified in dismissing all the remaining indictments and did it! It is to the great advantage of this region to put that blot on the judiciary of America behind us – hide it from sight as soon as possible, and open a brighter and better page in the history of the Nome region. It has fallen to my fortune to close the unfortunate page and open the brighter and better one, and if God gives me the strength of body to do the work, I will not fail to do my best.”

Wickersham’s first official judicial headquarters at the turn of the century was at Eagle, one of the largest settlements on the Yukon River. Here, after building his modest log home, Wickersham began settling mining claim disputes and collecting saloon license fees for the Third Judicial District, which comprised 300,000 square miles.

He then moved when Fairbanks became the center of gold mining. Along with trading post entrepreneur Capt. E.T. Barnette and prospector Felix Pedro, who discovered gold in the region, Wickersham is credited with founding the town and naming it Fairbanks, after Sen. Charles Fairbanks of Indiana. Sen. Fairbanks was elected vice president of the United States on Theodore Roosevelt’s ticket and served from 1905-1909.

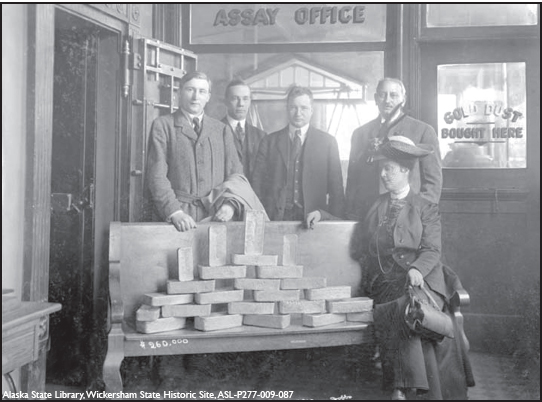

These gold bars, worth $260,000, represent one week’s output of the Pioneering Mining Company in Nome in July 1910.

During Wickersham’s first term of court, more cases were tried than ever before this time in all the other places combined in Interior Alaska. He rented a room in the building that was then Carrol and Parker’s Mill Office and opened the first Equity Court in town while a courthouse was being built at the corner of Second Avenue and Cushman Street. The Federal Building is located on the original site of that pioneer courthouse.

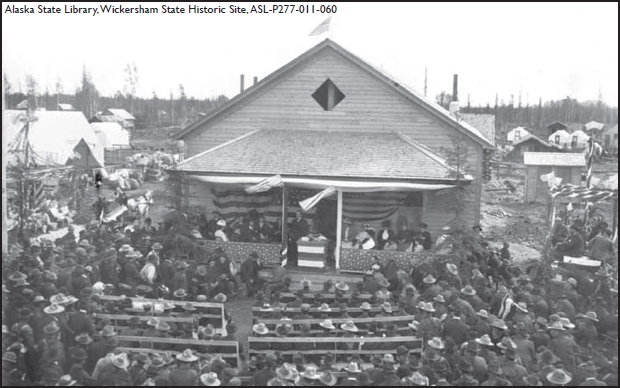

On July 4, 1904, when the courthouse was finished and officially dedicated, Judge Wickersham addressed a mass audience of townspeople and miners who had come in from the creeks for the holiday. In honor of the occasion, he was presented a gold spoon, the handle of which was made of four nuggets and the bowl pounded from a single gold nugget. The nuggets came from some of the original discoveries that started the young camp.

Judge James Wickersham delivers the Fourth of July address at the dedication of the first courthouse at Fairbanks in 1904.

So many firsts can be attributed to Wickersham that it’s difficult to know where to begin. He started the first floating court in Alaska, the first court ever held in the Aleutians. While serving as judge, he traveled thousands of miles by dogs and sled, on foot and on riverboats.

He also is credited with the first organized attempt to climb Denali, the Native name for Mount McKinley. Wickersham helped finance his 1903 expedition by publishing one issue of The Fairbanks Miner, the first newspaper in Fairbanks and the Tanana Valley. He produced only seven copies on a typewriter, using any decent piece of paper he could find, and sold them for $5 each. He also sold 36 ads at $5 apiece and arranged to have the papers read to audiences who willingly paid $1 admission to hear news of gold discoveries about which they already knew.

In 1915, he brought together all the Native chiefs of Interior Alaska and organized the first Indian Council held in Fairbanks to discuss the effects of the railroad and homesteading on the Native way of life – one of the earliest considerations of Native land claims in Alaska.

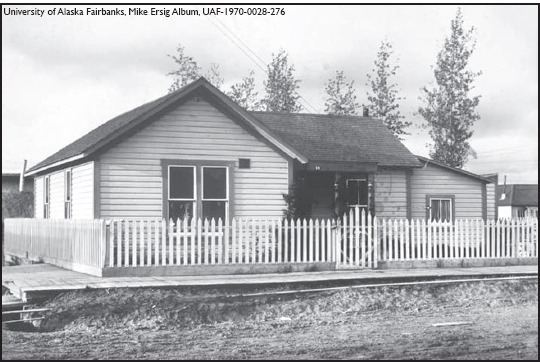

Judge James Wickersham lived in this frame house in Fairbanks during the early 1900s.

Wickersham resigned from the bench in 1907, practiced law in Fairbanks for a short time, and in August 1908, an overwhelming majority elected him as Alaska’s third delegate to Congress. Elected for five successive terms during this turbulent time in Alaska’s history, he was in the thick of struggles between conservationists, who wanted to save the resources from monopolists, and those who wanted to develop Alaska’s resources. Independent by nature, Wickersham ran on nearly every political ticket in the territory. And as one source suggested, “Wickersham could have been elected Jesus Christ, had he sought the office.”

While serving Alaska, Wickersham found the Library of Congress had no Alaska section. He remedied the situation by preparing a bibliography of Alaska literature, amassing 10,380 items in his tremendous undertaking – perhaps the most gigantic historical task ever attempted by a single man. Few things written about Alaska, either as a territory or as a Russian possession, escaped his attention. He collected many of the items for his own personal Alaska library, which later was acquired by the territorial library at Juneau.

Wickersham retired from politics in 1932 and lived in Juneau until his death in 1939. As his obituary aptly read:

“Alaska’s wick burns out, but his light shines on … Alaska will not forget James Wickersham. His place in our history is secure.”

And Evangeline Atwood, author of “Frontier Politics,” said, “… No other man has made as deep and varied imprints on Alaska’s heritage, whether it be in politics, government, commerce, literature, history or philosophy. A federal judge, member of Congress, attorney and explorer, present-day Alaska is deeply in debt to him.”

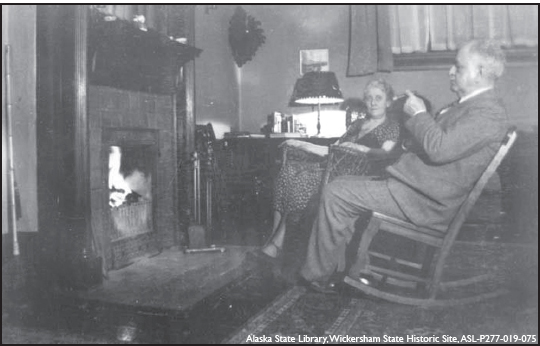

Grace and James Wickersham sit in front of the fireplace inside their home in Juneau, where the judge retired.