Murder rocked the gold-mining town of Juneau in 1909.

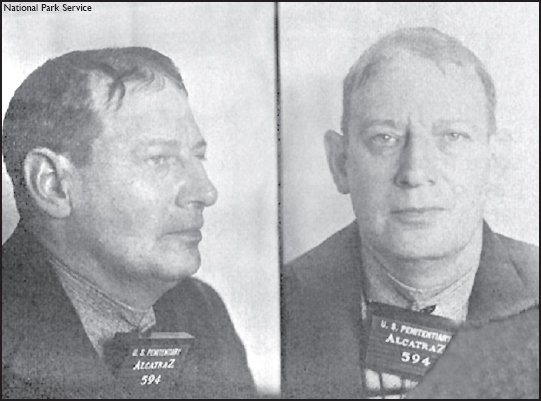

INMATE NO. 594

Before he became well known around the country, one of America’s most famous prison inmates dug gold nuggets out of a mine in Juneau during 1908.

His employment with the gold mine didn’t last long, however. After being dismissed as a troublemaker, he became a bartender and moved in with bar girl Kitty O’Brien on Gastineau Avenue. His relationship with her turned deadly the following year.

Murder rocked the gold-mining town of Juneau in 1909.

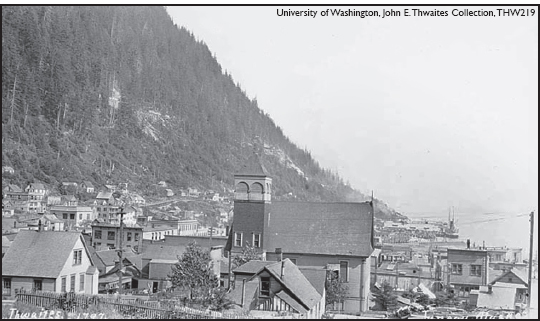

Located on the mainland of Southeast Alaska, Juneau was built at the heart of the Inside Passage along Gastineau Channel. The area was a fish camp for the indigenous Tlingit Indians. In 1880, nearly 20 years before the gold rushes to the Klondike and Nome, Joe Juneau and Richard Harris were led to Gold Creek by Chief Kowee of the Auk Tribe. They found mother lode deposits upstream, staked their mining claims and developed a 160-acre incorporated city they called Harrisburg. Miners later voted to change the name to Juneau, pictured above in 1912.

Thousands of prospectors flooded into the area.The city of Juneau was formed in 1900, and in 1906, the state capital was transferred from Sitka.

The Treadwell and Ready Bullion mines across the channel on Douglas Island became world-scale mines, operating from 1882 to 1917. In 1916, the Alaska-Juneau gold mine was built on the mainland, and it became the largest operation of its kind in the world.

In 1917, a cave-in and flood closed the Treadwell Mine on Douglas. It produced $66 million in gold in its 35 years of operation. Fishing, canneries, transportation and trading services and a sawmill contributed to Juneau’s growth through the early 1900s.

While most records concerning this case have been destroyed over the years, Deputy U.S. Marshall H.L. Faulkner recalled the events, according to Alaska State Troopers’ “50 Years of History.”

On the evening of Jan. 18, 1909, Nels Peterson spotted Faulkner walking home from the courthouse along Fourth Street in downtown Juneau. Peterson called to the marshal and told him he’d heard a gunshot come from a small two-room cabin next to his house and had seen a man run out of the building and down Franklin Street.

Faulkner slowly approached the cabin and then noticed the door ajar. He tried to enter, but soon discovered that a man’s body lay on the floor, blocking the entrance. The dead man, Charles F. Damer, had been shot through the heart.

Several hours later, the authorities identified the bartender, who would later become Inmate No. 594 at an infamous prison in California, as the prime suspect.

Faulkner and a Juneau police officer, James Mulcahey, investigated the murder. They learned that Damer and the suspect both vied for the affections of O’Brien and had had an argument earlier in the morning in one of the South Franklin Street saloons.

Some sources said O’Brien and the bartender were lovers, others suggested that she supported him and he was her pimp. Whatever the case, Faulkner and Mulcahey arrested the bartender later that evening at O’Brien’s cabin. While searching the premises, they found a revolver. Faulkner later recounted that the weapon proved to be “the instrument of the murder.”

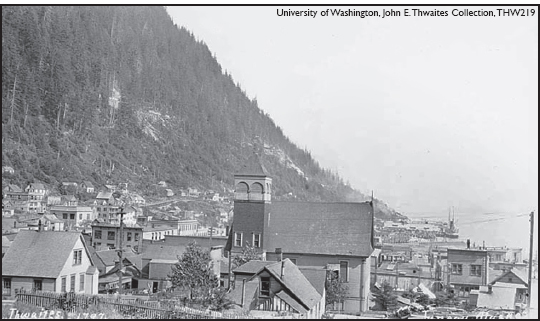

Wrongdoers were tried in the U.S. Courthouse in Juneau, pictured above behind City Hall.

Authorities questioned the bartender and O’Brien about the killing. O’Brien told the officers that Damer had struck her in the face during a quarrel, and she had told the bartender about the attack. The bartender then went looking for Damer, found him, and shot him to death. The bartender’s version of events added that O’Brien had pleaded with him to kill Damer for attacking her.

Justice in Juneau proved swift and sure. A coroner’s jury convened the evening of the murder, and after hearing testimony from the various parties, returned its verdict that Damer met his death at the hands of the bartender and named O’Brien as an accomplice.

Both the bartender and O’Brien were charged with murder and arraigned on Jan. 21. Authorities later dropped the charges against O’Brien, and the bartender pleaded guilty to a charge of second-degree murder. He was sentenced to serve seven years at the federal penitentiary on McNeil Island near Tacoma, Washington.

While the bartender served his seven-year sentence, his mother and sister continued to work in Alaska, spending most of their earnings on attempts to have him pardoned or paroled.

Authorities transferred him to the federal penitentiary at Leavenworth, Kansas, in 1912, due to ceaseless complaints about his threats toward other prisoners and overcrowding in the prison. He kept to himself at the maximum-security facility for hard-case prisoners. Convict Morris Rudensky described him:

“Physically he was a disgrace – tall, thin and as attractive as a barracuda or a herring bone without the herring. He seldom spoke to anyone, including the cons, and vice versa. He was a ferocious misanthrope.”

Just before the bartender’s scheduled release on March 26, 1916, he walked into the Leavenworth mess hall and stabbed to death prison guard Andrew F. Turner in front of 1,200 convicts and prison officials. No one knows why.

“The guard (Turner) took sick of heart trouble. I guess you could call it heart puncture. I never have given them any reason for my doing it, so they won’t have much to work on; only that I killed him, and that won’t do much good. I admit that much,” he later said to Rudensky.

Convicted of Turner’s murder, the bartender was sentenced to hang in April 1920. However, his mother successfully gained an audience with President Woodrow Wilson’s wife. She begged her to convince her ailing husband to spare her son’s life, since he was just beginning to gain a reputation as a lover of canaries and an expert on their diseases.

Elizabeth Bolling Wilson, impressed with the inmate’s pioneer work with birds, convinced her husband to commute the death sentence. The same week as the bartender was scheduled for execution, the president’s order arrived that changed the sentence to solitary confinement for the rest of his life.

The gold-miner-turned-bartender-turned-murderer named Robert Stroud carried on experimenting with canary diseases and ornithology while living in solitary in two adjoining cells.

Over the 30 years he was imprisoned at Leavenworth, he authored two books on canaries and their diseases, having raised nearly 300 birds in his cells, carefully studying their habits and physiology.

He also wrote a manuscript called “Looking Outward” about prison reform that was never published.

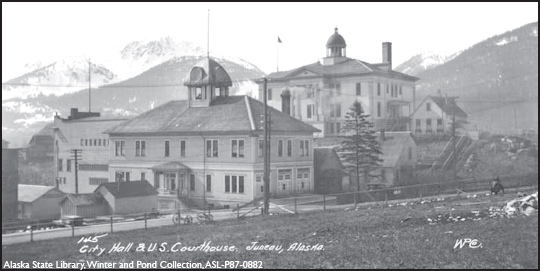

Stroud transferred to Alcatraz in 1942, where he became inmate No. 594 at the new maximum-security federal institution. He spent six years in segregation in D Block and 11 years in the prison hospital. In 1959 he was transferred to the Medical Center for Federal Prisoners in Springfield, Missouri, and was found dead there on Nov. 21, 1963.

After murdering a man in Juneau in 1909, Robert Stroud was sent to McNeil Prison in Washington state, followed by time in Leavenworth Prison in Kansas. In 1942, he was transferred to a cell in Alcatraz, pictured above.

Robert Stroud, shown above in this mugshot, became prisoner No. 594 at Alcatraz maximum-security prison in 1942.

His nickname, “The Birdman of Alcatraz,” came from his life on the rock. And his monumental work, “Stroud’s Book of Bird Diseases,” published in 1942, still is regarded as an authoritative source.