11

ALASKA’S FIRST SERIAL KILLER

Between 1912 and 1915, a number of single, unattached men mysteriously disappeared in Southeast Alaska. The few law enforcement officials in the territory were baffled, but a suspect finally emerged in the fall of 1915.

A Petersburg man named Edward Krause, who’d run for the Territorial Legislature as a Socialist Party candidate in 1912, represented himself as a U.S. marshal to officials at the Treadwell Mine in Douglas in mid-September. Krause told the bosses that he had a court summons for a mine worker named James Christie, according to Alaska State Troopers’ “50 Years of History.”

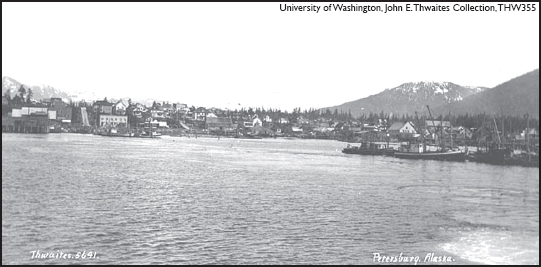

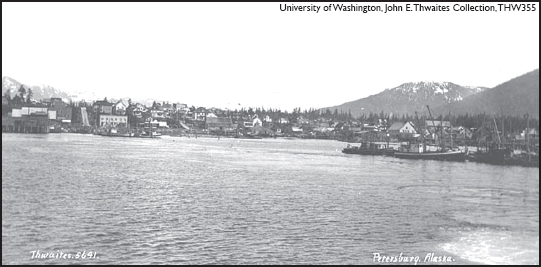

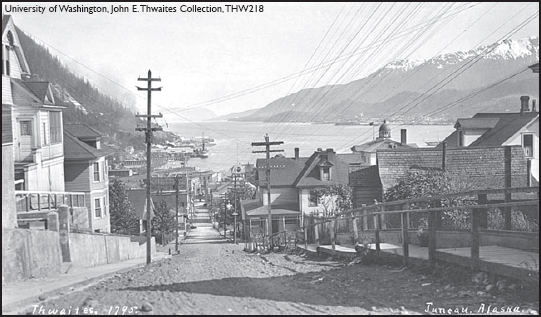

Alaska’s first-known serial killer lived in Petersburg, pictured above in 1912. Petersburg is located on the north end of Mitkof Island, where the Wrangell Narrows meet Frederick Sound. It lies midway between Juneau and Ketchikan, about 120 miles from either community in Southeast Alaska.

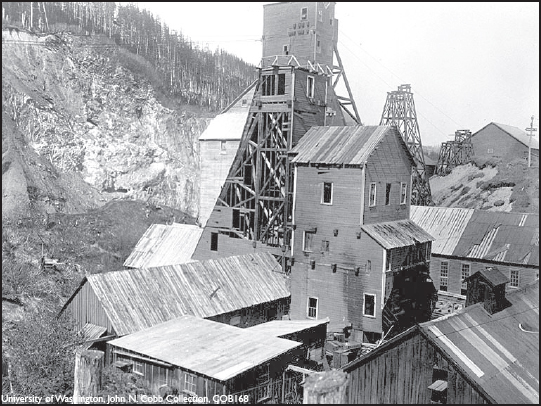

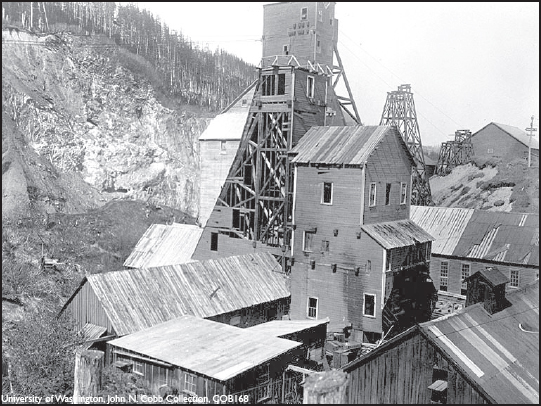

Edward Krause showed up at the Alaska Treadwell Gold Mining Company at Douglas Island, pictured above at the Glory Hole in 1911. He asked for a mine worker named James Christie, and that’s the last time anyone ever saw the unfortunate miner.

Christie departed with the bogus lawman and was never seen again.

The managers at the mine started an investigation of their own into Christie’s disappearance. They suspected it was associated with labor problems between the violence-prone local Western Federation of Miners and the company union, of which Christie served as an officer. When an offer of a reward brought no information, the Treadwell Mining Company hired the Pinkerton Detective Agency.

The Pinkertons had extensive experience investigating organized labor and earlier had been retained by the Treadwell Mining Company to infiltrate the Western Federation of Miners in Alaska. Like the managers of the company, the Pinkerton people thought Christie’s disappearance was related to labor rivalries. They believed that Krause, a radical socialist, was a hired killer engaged by the violent wing of the labor union.

When it was learned that Krause also was identified as the last person to see a missing charter boat operator out of Juneau, a warrant for his arrest was issued on charges of impersonating a federal officer.

Krause escaped the clutches of the law in Ketchikan and jumped onboard a steamer heading for Seattle. But a savvy passenger, who had seen posters plastered by the Treadwell Mining Company, recognized him as the man with a bounty on his head.

When the steamer docked in Puget Sound, police detectives were waiting. A search of Krause’s possessions turned up incriminating evidence, including forged documents, bank accounts and real estate transactions, which tied him to not only the recent disappearances in Juneau, but to the disappearances of at least eight other men, too.

After Krause was returned to Alaska, his true identity surfaced. Krause was really Edward Slompke, who’d served with the U. S. Army at Wrangell in 1897. By using forged documents, and stealing a military payroll, he deserted from the 12th U.S. Infantry in 1902 when his regiment was sent to China to participate in the Boxer Rebellion.

A yearlong investigation, which used the services of the newly formed Federal Bureau of Investigation, as well as the U.S. State Department, revealed a series of disappearances and an intricate pattern of forged property transactions.

Authorities found that over the years Krause recovered the assets of the murdered men. They also learned that a “murder gang,” run by Krause at Petersburg, was involved in additional mysterious disappearances.

Supporters of Krause, those in the radial Western Federation of Miners labor movement, thought the socialist was being framed by the capitalistic Treadwell Mining Company. Undercover government agents had to infiltrate the labor unions antagonistic to Treadwell to gain information about plans to get witnesses to change their testimony and threats to potential jurors.

Searchers combed the beaches and hillsides and divers probed the waters around Juneau throughout the spring and summer of 1916. However, none of Krause’s victims were found, so authorities had to rely on strong circumstantial evidence to try him.

Krause’s trials started in the spring of 1917. Among other charges, jurors found him guilty of kidnapping, robbery and forgery. His first murder trial, of Juneau charter boat operator James O. Plunkett, began in July.

To protect the jury from intimidation by Krause’s still-active supporters, the judge sequestered the jury during the trial – a first in Alaska court history. Krause’s trial also marked the first extensive use in Alaska of testimony from handwriting and typewriter experts.

Based on the overwhelming circumstantial evidence, the jury found Krause guilty of first-degree murder. His conviction was affirmed by the U.S. Court of Appeals in San Francisco, and Krause was sentenced to die by hanging at Juneau.

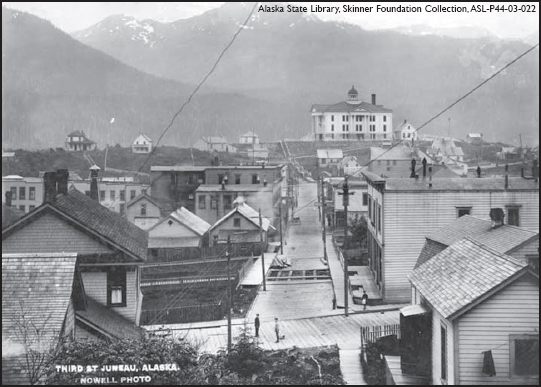

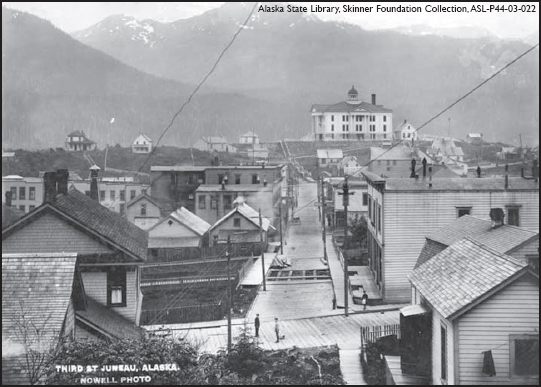

The U.S. Courthouse in Juneau, where Krause was tried, can be seen in the far background looking down Third and Gold with wooden streets and sidewalks.

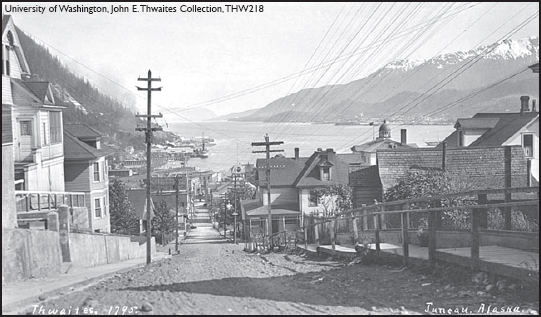

Even though investigators searched far and wide, none of Krause’s victims ever were found around Juneau, pictured here looking downhill toward town.

After sawing through the bars of his cell, Krause escaped from the federal jail in Juneau two days before his slated execution. That launched the most widespread manhunt in the territory’s history.

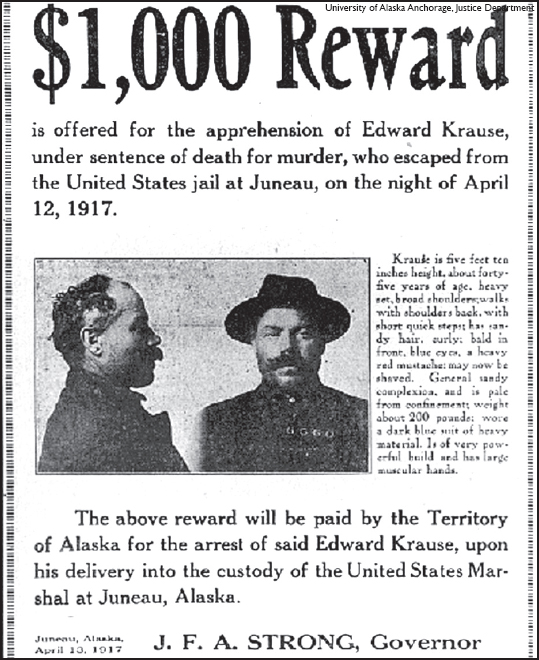

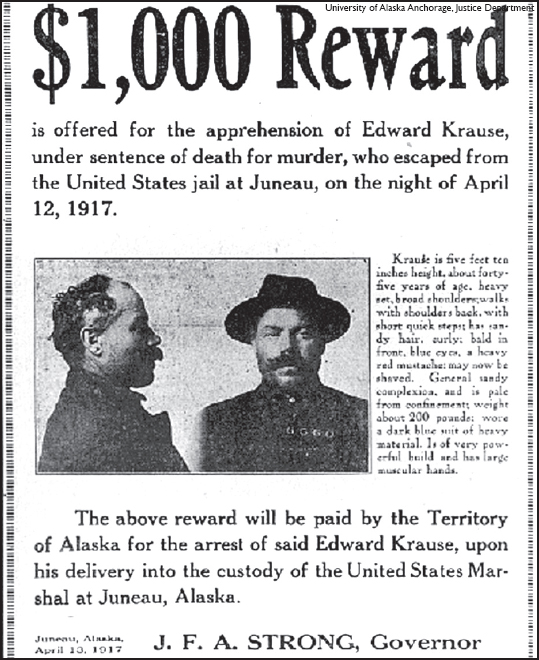

A notice of a reward for his capture appeared in the April 13, 1917, Juneau Daily Empire.

Fishing fleets in every community in Southeast mobilized to block Krause’s escape out of Alaska. The mines on both sides of Gastineau Channel closed down, and 1,000 miners joined in the hunt. While house-to-house searches were conducted, territorial Gov. John F.A. Strong announced his $1,000 reward, “dead or alive.”

A few days later, a homesteader claimed the reward. He’d killed Krause after the fugitive stepped out of a stolen skiff onto the beach at Admiralty Island.

“The true story of Krause’s criminal enterprises and their extent will never be known. But if the story could ever be told, it would undoubtedly be one of the most startling in the annals of American crime history,” stated a letter to the Department of Justice, written by U.S. Attorney James Smiser of Juneau.

The fine print reads:

“Krause is five feet, ten inches in height, about forty-five years of age, heavy set, broad shoulders; walks with shoulders back, with short quick steps; has sandy hair, curly; bald in front, blue eyes, a heavy red mustache; may now be shaved. General sandy complexion, and is pale from confinement; weight about 200 pounds; wore a dark-blue suit of heavy material. Is of very powerful build and has large muscular hands.”