John Clum arrived in Alaska in the late 1890s and set up the territory’s first post offices.

ROUTES TO RESOURCES

ARIZONA EDITOR MAKES MARK ON ALASKA

The colorful editor of the famous Tombstone Epitaph made his mark on Alaska in the late 1890s. But John Clum first gained fame in the 1870s as an Apache agent. He founded the Apache police force on the San Carlos reservation and was proud to proclaim himself “the only man to place Geronimo in irons.”

He also became the first mayor of Tombstone, and it was during this era that the legendary gunfight at the OK Corral was fought. At least one attack was made on Clum’s life, but he stayed with “the town too tough to die” until the economy of Tombstone was brought to a standstill with the flooding of the silver mines.

But it was another one of Clum’s ventures that brought him to Alaska and gave him the opportunity to leave his mark on the new land. In March 1898, he was appointed post office inspector for the territory. He and his son, Woodworth, spent the next five months traveling 8,000 miles around Alaska and the Yukon setting up new post offices and equipping others.

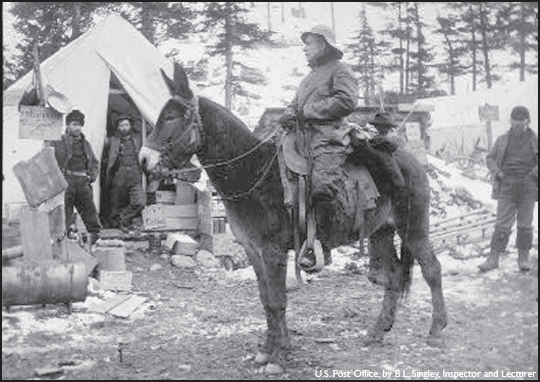

John Clum arrived in Alaska in the late 1890s and set up the territory’s first post offices.

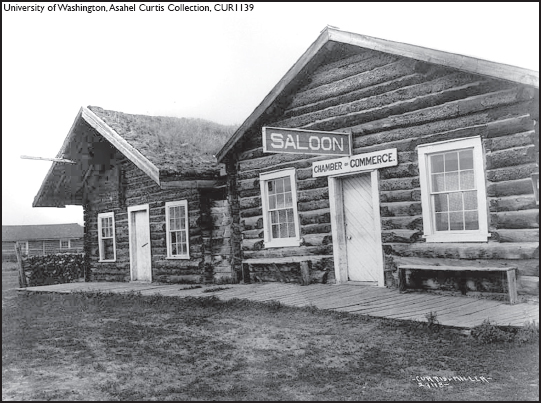

This log building at Eagle housed the Chamber of Commerce office in its saloon.

It was no job for a weakling – one of his inspection trips was made on “foot and in a snowstorm” to Chilkat, and a second trip, according to his diary, was via reindeer and “lap” sled. This was during the Klondike stampede days and thousands of gold seekers were flooding the country. They wanted mail service, and Clum gave it to them as rapidly as possible.

He established post offices in Southeast Alaska at Sheep Camp, the last station before the Chilkoot Pass, Pyramid Harbor and Canyon. Clum reestablished the post office at Haines and reorganized the offices at Skagway and Dyea.

Then he started down the Yukon. Equipped with a 100-pound, 18-foot Peterborough canoe, he carried about 1,000 pounds of supplies, including mail sack keys, postal stamps and cards, and dating and canceling stamps. He found prices steep everywhere, he wrote in his diary. A bowl of soup at a restaurant cost $1, as did a one-minute dance with a dancehall girl. Eggs cost $18 a dozen, sugar $100 a sack.

Over the Yukon Trail, Clum and his son traveled to Dawson, which Clum noted was “the Coney Island of the Northwest … wild and wooly – streets filled with surging masses from 9 a.m. until 2 a.m.”

From Dawson, he traveled to Eagle via Fortymile. At Eagle, he established the first new post office of the Interior, and then traveled 18 miles down the Yukon River to set up another post office at Starr, located at the mouth of Seventymile River. His next stop was Circle, where the first post office on the Yukon River had been established in 1896. He found the post office there, under Jack McQuesten, “in good order.”

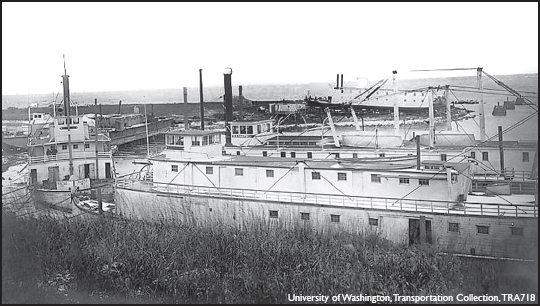

On July 1, 1898, he and his son boarded the steamer Seattle No. 1 for its maiden voyage down the Yukon to St. Michael, stopping to establish post offices at Fort Yukon, Rampart, Weare, Koyukuk, Nulato and Anvik. The boat reached St. Michael on the evening of July 9, and Clum sent 1,000 pounds of mail, the first to go back up the Yukon, on the steamer Bella.

Sternwheelers Seattle No. 1 and Seattle No. 2 sit along the banks of the Yukon River in 1899.

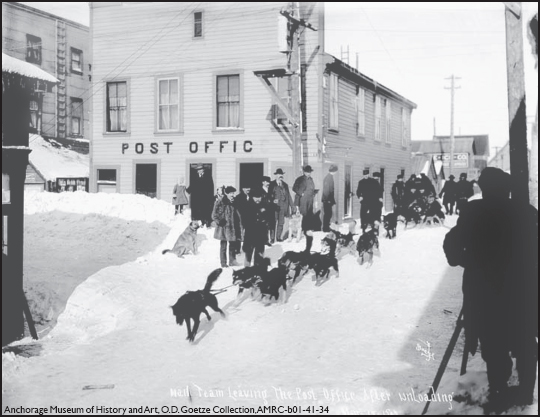

People stand in front of the Nome Post Office in 1907 and watch a mail delivery dog team head back down the trail after it delivered mail.

Now that he had the Yukon and the Interior supplied with post offices, Clum took a ship to the Aleutians, changed the name of the post office at Ounalaska to Unalaska, then voyaged into Cook Inlet and set up post offices at Tyonek, Sunrise and Homer and arranged for one at Seldovia. He next proceeded to Prince William Sound, checking on the post offices at Nuchek and Orca.

The postal system he set up put Alaska in touch with the United States, and when the Nome stampede occurred, Clum became a special agent in Alaska for the Post Office Department. He extended postal service to the north Bering Sea coast, and established a semiannual monthly mail run between Nome and Point Blossom. For the next five years, he alternated between summers in Alaska and winters in New York City, but in 1906 he came back to Alaska to be the Fairbanks postmaster.

He dabbled in Alaska politics, too, as well as mining ventures, but wasn’t too successful in either. His mining prospects never showed a profit, and when he ran as an Independent candidate for delegate to Congress against James Wickersham, he was soundly trounced.

But Clum successfully fulfilled his duties as the “Post Office man in Alaska,” and his efforts to improve the territory’s postal facilities were greatly appreciated. He resigned as the Fairbanks postmaster in 1909 and left Alaska. His daughter, Caro, after whom the settlement of Caro was named, stayed on, marrying Peter Vachon, owner of the Tanana Commercial Company.

Clum died in 1932 at the age of 81, three years after serving as a pallbearer for his lifelong friend, Wyatt Earp. As Clum’s friends mourned his death, one noted that it was “a sign of the passing of the Old West.”

But other rugged individuals continued to deliver mail throughout Alaska in all types of weather and travel conditions.

U. S. Postal Inspector John Clum, above, sometimes traveled by mule through parts of Alaska as he established post offices in the Last Frontier.

Scores of prospectors gather their gear together in Dyea, as they prepare to head toward the Chilkoot Trail during the Klondike Gold Rush.

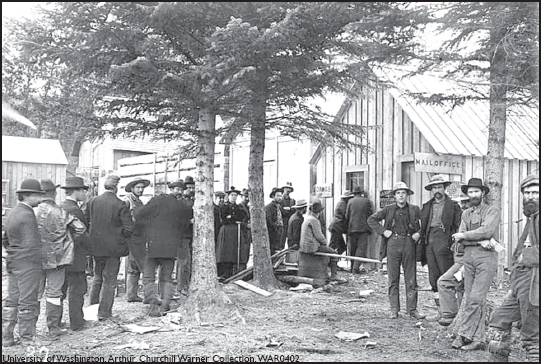

Stampeders stand in a long line waiting for mail at the Dyea post office.