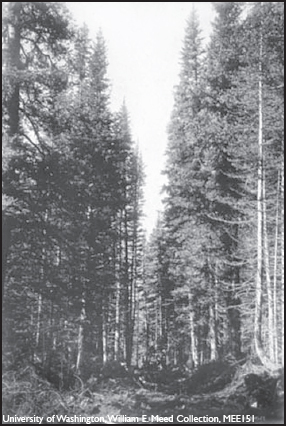

The abundance of tall trees in Southeast Alaska kept sawmills humming.

DALTON TURNS TIMBER INTO GOLD

A short, stocky and feisty frontiersman named Jack Dalton had explored much of Southeast Alaska by the late 1890s. He’d established a toll road from Pyramid Harbor on the Lynn Canal to the Yukon, on which around 2,000 cattle had traveled and made a welcome addition to many a miner’s food supply during the Klondike Gold Rush. His trail would later become part of the Haines Highway.

When the entrepreneurial Dalton had an area around the Porcupine gold field surveyed – 36 miles from Haines up the Chilkat Valley – he realized that more gold lay in the forested area surrounding the town site. He built a sawmill in 1899 that produced 5,000 board feet of lumber a day. The sawmill also made lumber needed for large flumes for the gold-mining effort.

The abundance of tall trees in Southeast Alaska kept sawmills humming.

Loggers, standing atop a pile of cut timber, show just how big trees grow in Southeast Alaska.

However, the Tlingit Indians began using the timber resources of Southeast Alaska centuries before Dalton happened upon the area. They burned wood for heat, made dugouts from cottonwood trees, carved household and ritual items, and stripped bark from cedar trees for weavers of Chilkat blankets.

When non-Natives began settling the area, bringing a cash economy with them, the Natives supplied the new settlers with firewood. Soon that became the most common service provided by the Natives for the newcomers. A cord of wood – 4 feet by 4 feet, cut and stacked – cost $2.

While small sawmills like Dalton’s could accommodate the needs of most miners for building homes and businesses, as well as construction in the gold fields, the majority of the lumber for major projects was sent via steamship from Seattle or Olympia, Washington, or from Portland, Oregon.

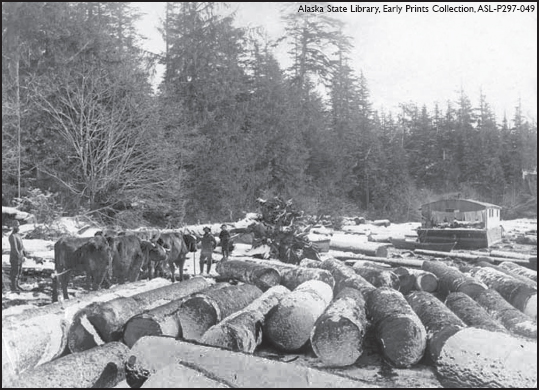

A plentiful supply of timber around Skagway helped furnish material for industry and a growing population.

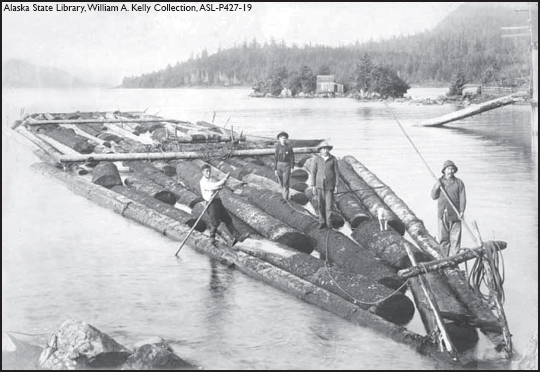

Four men raft several logs downriver to a sawmill in Southeast Alaska.

Quite a bit of lumber from outside of Alaska was used to build Haines’ Fort Seward and many local canneries, although some of the early canneries had small, private mills to use in making fish traps and other small construction projects.

Other sawmills operated in various communities, as well, including Skagway, Wrangell and an operation at the village of Port Gravina, near Ketchikan, where Tsimshian Indians from Metlakatla had settled in 1892. Their sawmill was the first business built, owned and operated by Natives in Alaska, according to historian Pat Roppel.

“The company constructed a sawmill with a wharf that unfortunately went dry at low tide,” Roppel wrote in “An Historical Guide to Revillagigedo and Gravina Islands” in 1995. “Powered by steam, the sawmill had a daily capacity of 15,000 board feet of sawed and planed timber.”

The sawmill initially produced box shooks for salmon boxes for the canned salmon industry that just was getting started, but soon the area construction boom had the mill primarily supplying lumber for buildings in Ketchikan and Saxman.

In 1905, Congress transferred the national forests to the U.S. Secretary of Agriculture and provided that pulpwood or wood pulp manufactured from Alaska timber could be exported. However, without a large outside market, the timber industry remained small, mainly producing firewood.

Sometimes loggers used oxen as work animals, as seen here on the Stikine River near Wrangell in 1864.

The Combs Lumber Company built a mill in Haines in 1907 that had a capacity of 25,000 board feet. Proclaimed by local newspaper advertisements as “the largest saw and planing mill on Lynn Canal,” the mill burned down in 1912.

Industrial-scale logging didn’t begin until the 1950s when the U.S. Forest Service signed 50-year contracts with Ketchikan Pulp Company and foreign-owned Alaska Pulp Corporation, developing a timber industry within the Tongass forest.

Following his sojourn with timber in Southeast Alaska, Dalton next tackled opening a route to other riches in Southcentral Alaska.