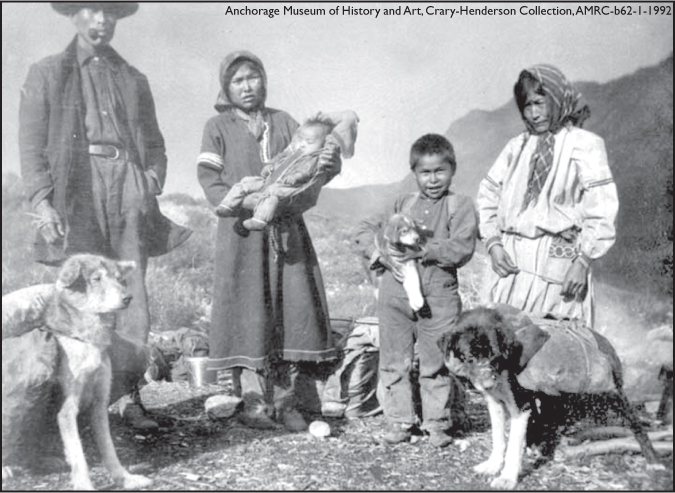

Alaska’s Natives relied on pack dogs to transport fish and supplies between seasons.

SLED DOGS LEAD THE WAY

Sled dogs have an illustrious history in the North Country, from the early days of Native settlements to the gold-rush booms during the 1890-1900s.

Alaska’s Natives relied on pack dogs to transport fish and supplies between seasons.

Early Russian fur traders added handlebars to sleds and trained lead dogs in order to use dog teams as a means of transportation through Alaska’s wilderness.

Natives of Alaska, northern Canada, Greenland and Siberia used dogs as winter draft animals for centuries. Russians arriving in western Alaska during the 1700-1800s found Alaska Natives using dogs to haul sleds loaded with fish, game, wood and other items.

The Natives ran ahead of the dogs as they guided them on the yearly trips between villages and fish and hunting camps. Russians improved the sled dog system by adding handlebars to sleds and harnessing dog teams in single file or in pairs. They also trained the dogs to follow commands given by sled drivers and introduced the “lead dog” or leader.

Russian exploration via dog teams was limited to Alaska’s coasts, as well as along some rivers, and followed existing Native trails between villages. Both Natives and Russians found frozen rivers also made useful winter trails.

Extensive use of dogs for long-distance transportation developed as gold discoveries were made in the late 1890s and early 1900s. Stampeders quickly learned that dog teams were worth their weight in gold. Thousands of dogs were imported from the contiguous states to help prospectors and adventurers reach the gold fields.

By the turn of the century, dog teams were helping cheechakos blaze new trails to establish law and order, develop mail routes and transport gold-crazed prospectors to new strikes north and west of Prince William Sound.

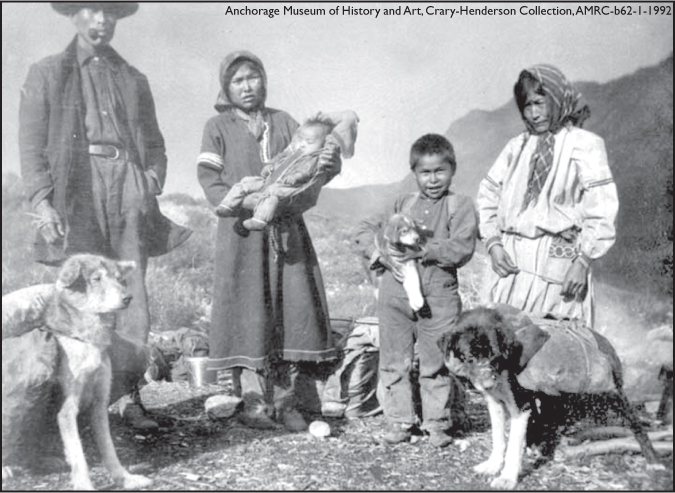

Frank L. Tondro, also known as The Malamute Kid, and his sled dog team pull up in front of the Valdez Mercantile around 1906.

From Valdez, a route was blazed to the Interior boomtown of Fairbanks. It became known as the Valdez-Fairbanks Trail. Sled dog teams, freight dog teams and mail teams streamed back and forth across that trail for many years.

From Seward, winter trails developed north and west. Russians and early traders and prospectors found traces of gold along the Kenai Peninsula, but the first major find did not occur until 1891. Al King, a veteran prospector from the Interior, working with gold pan and rocker, located gold on Resurrection Creek in Southcentral Alaska.

The Turnagain Arm Mining District boomed in 1895-1896, with about 3,000 people flooding into the area and mining mostly around the log-cabin communities of Hope and Sunrise.

Roughly blazed sled dog trails connected the communities of Sunrise, Hope and scattered trading posts at Resurrection Bay, Knik Arm and the Susitna River. Miners and merchants also combined to build a wagon road from Sunrise up Six-Mile Creek along the mining claims.

When winter came, some miners hooked up their dogs and pulled Yukon sleds loaded with needed supplies up the Kenai, Susitna, Knik or other rivers and made camp at promising locations. They then spent the winter thawing ground and digging gravel. At spring breakup, the prospectors sluiced the hoped-for gold from pay dirt. At season’s end they built rafts or poling boats and floated with their dogs back downstream to the trading posts or towns. This is the way the land was prospected.

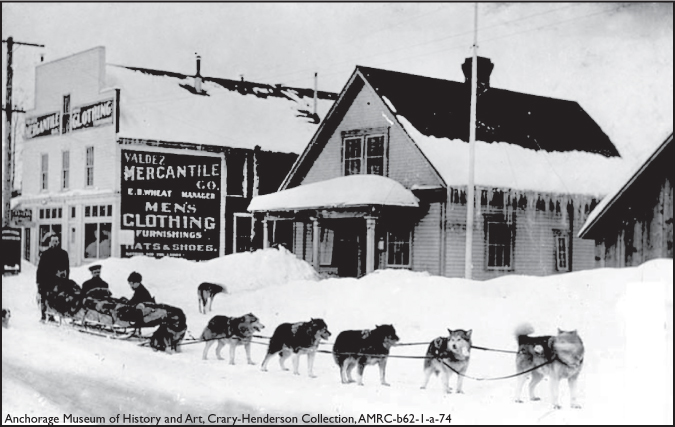

A dog team rests in front of the Pioneer Roadhouse in Knik.

The main trail from Seward to the various prospects in Southcentral Alaska traveled along the railroad right of way to Turnagain Arm, then along the north side of the Arm to Girdwood and over Crow Pass. It dropped into the Eagle River valley, to the Indian village of Eklutna and then around the upper end of Knik Arm to Knik.

By 1905, dog teams were carrying mail over 180 miles of trail between Seward and Susitna Station, a steamboat stop on the lower Susitna River that served as a supply point for dozens of mines in the foothills of the Alaska Range. The system of trails extended as goldfields were discovered to the north in the Talkeetna Mountains and the Yentna River drainage.

And when gold was discovered along the Innoko River around 1906-1907, another trail was forged that would become one of the most famous sled dog trails in history – the Iditarod Trail.

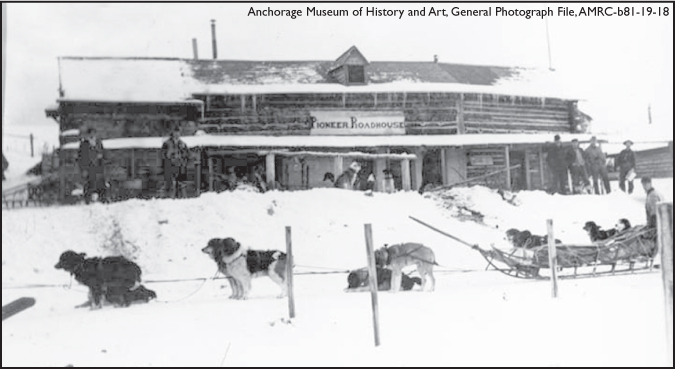

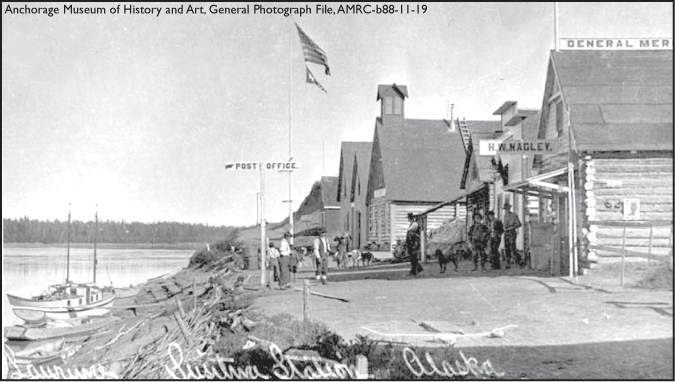

Susitna Station was a steamboat stop along the lower Susitna River.