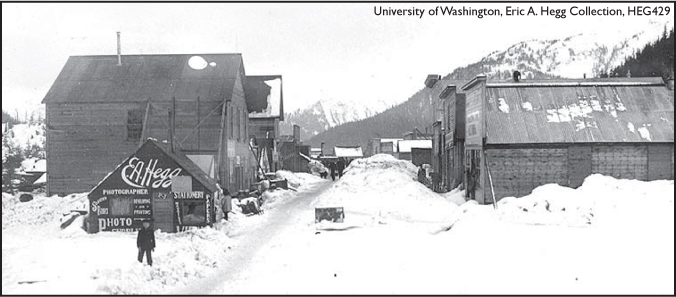

This scene of Cordova along Main Street in 1908 is similar to that which met artist Eustace Paul Ziegler’s eyes when he stepped ashore in the Prince William Sound town a year later.

SOURDOUGH PREACHER PAINTER

One of Alaska’s early artists stepped ashore in the boomtown of Cordova in 1909. His works aptly capture the epic struggle of sourdough days, portraying that historic period when pioneer men and women conquered a rugged wilderness and opened the Alaska frontier. The hunched backs of prospectors, bowed under heavy packs; the white, desolate tundra; powerful, winding rivers; the frigid majesty of snowy mountains, and small fishing boats boldly defying the mighty oceans fill Eustace Paul Ziegler’s canvases.

This scene of Cordova along Main Street in 1908 is similar to that which met artist Eustace Paul Ziegler’s eyes when he stepped ashore in the Prince William Sound town a year later.

Eustace Paul Ziegler’s “Native Woman,” oil on masonite, is on display at the University of Alaska Fairbanks Museum of the North.

His paintings show man challenging a nature he cannot conquer, but by hope and strength can learn to live in. If now and then we lament the passing of those vivid days, we can renew our spirits before Ziegler’s paintings, for he dipped his paint bush into life as it was lived in the rough and rugged days of Alaska’s youth.

Ziegler, himself, was just a youth when he arrived in Cordova to take charge of its Episcopal mission. It was a cold, snowy, windy day in January when Capt. “Dynamite” Johnny O’Brien tied the Yakutan up to the wharf, and the short, slightly built 22-year-old disembarked.

Fresh from the Yale School of Fine Arts and conventionally dressed, Ziegler must have been a shock to the thousands of roughly dressed pick-and-shovel “stiffs,” lumber jacks, miners, engineers, dynamiters, surveyors, adventurers and what-not who had “floated in with the tides and the ties” to build the Copper River and Northwestern Railway from tidewater to the Kennecott copper mines in the Interior. Probably as much a shock as the sight of the rough construction town was to him.

The Rev. E.P. Newton, Episcopal minister based at Valdez, had visited the new construction camp two years before and had seen the need for a meeting place, other than saloons, for the homeless, drifting men. The Episcopal Bishop of Alaska, Peter Trimble Rowe, and Michael J. Heney, in charge of building the railroad, helped him obtain a tract of land to start a mission.

Lumber was scarce and put up for sale to the highest bidder.

There were two – a saloon keeper and Newton. The saloon keeper outbid the Episcopal minister, and he got the lumber. However, even though a saloon became the first building in the new town, the mission was the second to be started.

Newton built a bright-red building, and coupled with the name St. George Mission, it gave rise to its nickname the “Red Dragon.” By 1908, the mission was ready to compete with the 26 saloons that now graced Cordova’s main street.

When Ziegler arrived to take over the Red Dragon’s “ecclesiastical proprietorship,” it did not take him long to fit into his new life. He might have been a cheechako, but he was no tenderfoot. Although he looked deceptively slight, he’d spent summers on logging crews in the north woods of his native Michigan, and he was a dead shot and an excellent camp cook.

Soon he was friends with saloon keepers, company bosses, bar swampers, teachers, doctors, prospectors, trappers – he was “Zieg” to everyone, and everyone was welcome at the Red Dragon. Before its warm, friendly fireplace, wastrels and gentlemen, workers and strays gathered to sleep, wrangle, fight, read, visit, sing and play the piano. On Sundays, however, an altar was let down by block and tackle from the joists above, a screen was drawn and services were held before it by Ziegler, whose mission was to minister to men’s souls as well as their bodies.

He passed a help-yourself box, which was a two-way collection plate. Hard and folding money could be taken by those in need, no receipts necessary, and repayments for years exceeded the amounts taken.

The frontier mission and Ziegler supplied warmth, cheer and aid to those who came seeking. They acquired a reputation far and wide for the services they rendered – religious as well as secular.

It had been a long way for young Ziegler to travel, but a love of the outdoors and the North had always been his. He also loved art.

When he was 7, he had decided that above all he wanted to paint. He worked at many art jobs, studied at the Detroit Art School and graduated from the Yale University of Fine Arts. After graduation, he still had to realize his dream of hitting the trail north, but Bishop Rowe was a family friend, and the young artist offered to help him.

Ziegler was secular superintendent in the boomtown of Cordova from 1909 until 1916. Then, shortly after his marriage to Mary Boyle, he became ordained as an Episcopal minister as his father and brothers before him. It was said, “he married the elite of the town and buried with Christian decency the remains of murdered vagabonds.”

“Zieg” was a friend of everyone and known all over the territory as he traveled up and down the coast in connection with his work. But he also painted constantly. He decorated the walls of the Red Dragon, and the church that was later built, with paintings of great beauty and deep religious feeling.

At Stephan’s Church at Fort Yukon were hung canvases depicting the nativity and the crucifixion that he copied from the great masters for the Native parishioners of that village church. All the time, too, he was painting the natural beauty he saw in every direction, and the people around him went on canvas, too – the trappers, fishermen, prospectors and Natives of the Copper River Valley and all over Alaska. There was Horsecreek Mary, for instance, an old Native woman who lived in a hovel near Chitina. He painted a beautiful study of her wrinkled, brown face.

One of his most famous paintings was the “Arctic Madonna.” The Eskimo mother and her placid baby won innumerable prizes and hung in many galleries. His sympathy and affection for the Native people of Alaska shines through his paintings, and the feeling was reciprocated. Chief Goodlataw of the Chitina Indians called the young preacher-painter, who brought food and clothing to his people, “George Jesus Man.”

His canvases were growing in character and strength with the fundamental realism of the rough and tough mining camps and the work-a-day world around him. For years, Ziegler traveled about Alaska seeing and painting everything he could – in oils, watercolor, woodcuts and dry point – as he recorded the pioneer scenes. Tourists bought his work from the windows of local stores. And one 16-by-20-inch oil painting for sale in Fursman’s drugstore in Cordova changed the direction of Ziegler’s life.

Ziegler painted realistic portrayals of life in gold-mining camps, like the painting above titled “Prospector’s Cabin,” oil on canvas board, which hangs in the Museum of the North at the University of Alaska Fairbanks.

Ziegler was on a dog team trip with Bishop Rowe in the Chitina region when he received a telegram saying that one of his paintings, a mountain scene, had been sold for $150 to E.T. Stannard, president of the Alaska Steamship Company. Stannard later asked Ziegler to come to Seattle and do a series of murals for the company’s Seattle offices.

Bishop Rowe convinced his young friend to grasp the opportunity, and practically lifted him off his snowshoes and headed him on the new trail that was to bring him fame in the world of art.

When the murals were completed, the Zieglers returned to Cordova, but new offers flooded the little Alaskan minister. He finally had to make a choice between the ministry and a career as an artist. By this time, Cordova had tamed considerably and was a respectable young city with families, a school and churches. The old, rough, frontier days were gone.

Eustace Ziegler’s friend, Bishop Peter Trimble Rowe, center, poses with Delatuck, a Kobuk Eskimo, and Maggie, an Athabascan Indian, in the Koyukuk region in 1922.

Ziegler, who fit the Red Dragon during its early mission days, no longer felt needed. As he humorously said later, “I resigned 10 minutes before Bishop Rowe fired me.”

The Zieglers and their two daughters, Betty and Ann, moved to Seattle in September 1924, and from then on his art career grew. His paintings found their way into the White House, governors’ mansions, art museums and collections, and he won innumerable prizes, awards and citations.

Many of his paintings hung in the Seattle museums; his religious works hung in many Pacific Northwest chapels, and many of his powerful portraits and landscapes, commissioned by wealthy patrons, now reside in the Pacific Northwest museums and universities.

His canvases also are in the homes and hearts of ordinary people. Alaskans who best know the subjects he painted in his early Alaska days like his works so much that some of them own 20 or more of his canvases. They feel that he is one of theirs, and that is how he felt to the end. Once he was asked if he could be called an “ex-sourdough,” and he replied, proudly and sternly, “I’m a sourdough. There’s no such thing as an ex-sourdough!”

He renewed his ties with Alaska nearly every summer, traveling to different areas to paint. Like another famous Alaska artist, Sydney Laurence, one of Ziegler’s favorite subjects was Denali, which he often called “his studio.” He painted the majestic mountain, first from the Denali National Park and Preserve, packing in supplies 80 miles by pack train, then later working from Talkeetna. In June 1931, he and his pupil, Ted Lambert, made a trip down the Yukon River from Fairbanks to Bethel, painting the subjects they liked as they went.

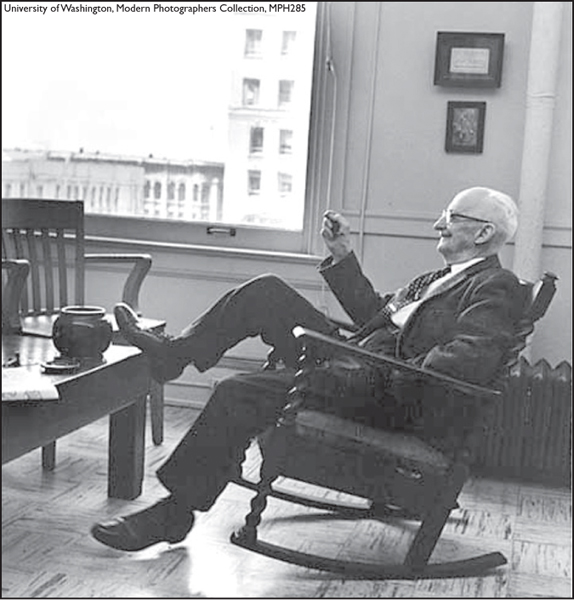

At an age when most men were forced into idleness, Ziegler in his late 70s was still painting and had no plans to retire. He was turning out one or two pictures a week, working from about 8 a.m. to midnight, five days and sometimes on Saturdays. At the time, one interviewer characterized him as a “silver-haired, peppery little artist, who at 79, enjoys good health, which bubbles to the surface of his sharp features.”

In 1969, however, at the age of 87, the old sourdough came to the end of his trail. At the time of his death, the Frye Museum in Seattle was exhibiting 63 of his works. He once estimated he had painted or drawn more than 50 works a year since he began selling professionally at the age of 20. A realist, he painted what he saw, and power and meaning spoke so strongly through his paintings that they brought him prosperity as well as artistic success.

Perhaps one of his own statements explains that success: “If you don’t paint for money, you’ll make money.”

His old friend, Bishop Rowe, once wrote of him:

“To know Eustace Ziegler was to know an unforgettable person. Few workers in the Alaska mission field were better known, or more beloved by the men who follow the frontier. He possessed a rich sense of humor, was a unique storyteller, a diligent pastor and a lover of mankind.”

Although his paintings saw man stripped of stature by a wilderness he could never conquer, Ziegler believed that by hope and strength drawn from his fellow man, man can live in that wilderness. That hope and strength can be sensed in his paintings for he has expressed eloquently much that is fundamental in this business of being alive and aware. He was a fitting interpreter of the Great Land, and a fitting choice for Alaska’s Hall of Fame, which inducted him in the early 1970s.

Eustace Ziegler, pictured here in May 1965, became famous for painting scenes of life in Alaska.