Mount St. Elias has proved to be a difficult mountain to summit in the more than 250 years since it was first spotted by white men.

ELIAS: TOUGH EVERY FOOT OF THE WAY

Mount St. Elias, the first point sighted by white men on the mainland of Alaska in 1741, has proved a mighty challenge to mountaineers. Only a handful of climbers have conquered it in the years since the Dane, Vitus Bering, discovered and named it for Russia.

Mount St. Elias has proved to be a difficult mountain to summit in the more than 250 years since it was first spotted by white men.

English explorers George Dixon and James Cook noted the mighty mountain, too, in their explorations, and in 1786, Comte de La Perouse’s astronomer, Joseph Lepaute Dagelet, calculated its altitude at 12,672 feet. A few years later, Spanish explorer Alejandro Malaspina determined its altitude at 17,851 feet, remarkably near its true height of 18,024 feet as decided upon by Coast Survey Triangulation in 1892.

The area around Mount St. Elias contains an important grouping of Athabascan prehistoric and historic archeological sites of the Tlingit and Eyak Indians and the Chugach Eskimos, including Taral, Cross Creek and Batzulnetas.

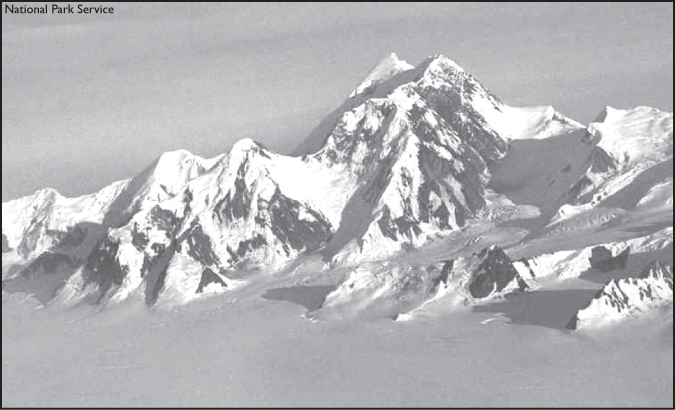

But nearly 150 years went by after Bering’s discovery before any attempt was made to ascend the vast, barren mountain, rearing upward from the shore of the sea. Capped with snow and draped with glaciers that wind upward and back as far as the eye can see, the mountain, according to many mountaineers, presents the greatest snow climb in the world. The line of perpetual snow descends to only 400 feet above sea level.

To accept the challenge in 1886, Lt. Frederick Schwatka, accompanied by professor William Libbey and Sir Henry Seton-Karr, led an expedition supported by the New York Times. The expedition failed, however, because so little was known of the conditions that were encountered. The party made it about 20 miles inland and obtained considerable geographical information that was valuable to subsequent explorers.

Sir Henry Seton-Karr, pictured here at age 61, was a noted outdoorsman and former member of the British Parliament. His attempt to climb St. Elias failed in 1886.

As Seton-Karr described the effort in his book, “Shores and Alps of Alaska:”

“… had the weather been clear, we might have picked out a possible way of ascent and might even have seen part of the northern face on which no white man’s eye has yet rested, but compelled by all these circumstances over which we had no control, we returned to camp. I had ascended to a greater height over the summer snow level than is possible to accomplish in Europe.”

Seton-Karr described Elias as forming a regular quadrilateral pyramid, the first feature as seen from Icy Bay; one also sees a detached, circular, crater-like basin nearly halfway up the central front, then one notices the regularity of three of the pyramidal side ridges and assumes that the fourth ridge must be equally regular. One notices, too, according to Seton-Karr:

“… the solitary and isolated situation of the Ice King – the termination and crowning elevation of his range, so close upon the sea, going out over the widest ocean of the world.”

Two years later, in 1888, a party of three Englishmen – W.H. Topham, Edwin Topham and George Broca – and American William Williams found their way to the summit blocked by a 1,500-foot-high mound of ice at the 11,400-foot level. They decided that a temporary camp and the services of experienced packers would be needed to go any farther, so they concluded the southwestern face of Mount St. Elias would never be climbed. Williams wrote:

“It presents a mass of broken snow, beautiful, yet forbidding … the whole scene surpassed in grandeur, though not in picturesqueness, the very best that the Alps can offer. Roughly speaking, the eye encounters for miles nothing but snow and ice. I had never before thoroughly realized the vastness of the Alaskan glaciers … the groups of snow-clad peaks visible to the naked eye were countless; and to the northward, in which direction the view was barred, their number is doubtless quite as great.”

Under the joint auspices of the National Geographic Society and the U. S. Geological Survey came the third attempt to reach St. Elias’ summit. In 1890, professor Israel Cook Russell led a party composed of Mark B. Karr and six camp hands. Russell and Karr undoubtedly would have reached the top if a severe storm had not forced their retreat after a four-day wait in rude shelters, in snow banks, without fuel and almost without food. As Karr later wrote:

“I lay there in my snowy camp and began to wonder if I would be found in future ages, preserved in glacier ice like a mammoth or cave bear, as an illustration to geologists that man inhabited these regions of eternal ice, living happily on nothing, breathing the free air of prehistoric times.”

He finally left his snowy shelter, but he realized that the party was too late to reach their instruments and again attempt the peak.

“If the storm had only held off for 24 hours more, the scalp of Elias would have been in our belt, and we could have finished the trip with great rejoicing. However, our attempt was bold, and our success in finding and naming new peaks, new glaciers, and studying their movements, and indeed, making a general topographical reconnaissance of this unknown region, recompensed us in part for failure in reaching the summit.”

Russell tried again in 1891, and while alone, reached a height of 14,500 feet. Heavy storms again forced his retreat, but from his height, he got a glimpse of the unknown region to the north. He wrote:

“I expected to see a comparatively low, forested country, perhaps some sign of human habitation. What met my astonished gaze was a vast, snow-covered region, limitless in expanse, through which hundreds, perhaps thousands, of bare, angular mountain peaks projected.

“There was not a stream, not a lake, and not a vestige of vegetation of any kind in sight. A more desolate or utterly lifeless land one never beheld. Vast, smooth snow surfaces without crevasses, stretched away to limitless distances, broken only by jagged and angular mountain peaks.”

But the route that Russell had explored was of great assistance when, in 1897, the mountain finally was conquered by one of the world’s most distinguished mountain climbers and explorers, the Italian Duke of Abruzzi. Born to King Amadeus of Spain, who was also the Duke d’Aosta in Italy, his full name was Luigi Amedeo Giuseppe Maria Ferdinando Francesco.

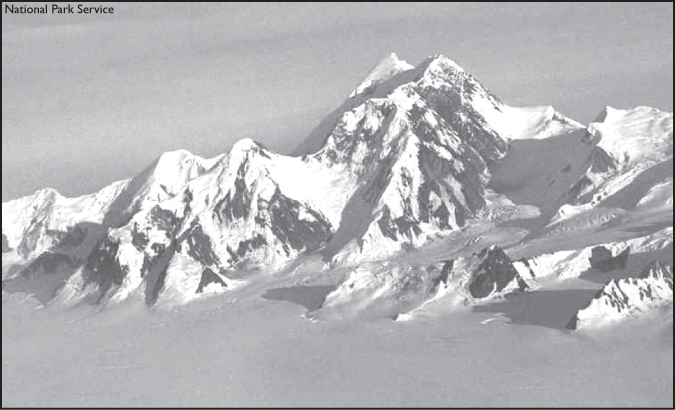

The duke and his party landed at Yakutat Bay, and with a large and thoroughly equipped expedition, made their way across the 40 miles of snow and ice between the coast and the base of the mountain. Crossing the Malaspina, Seward and Agassiz glaciers, the duke’s party ascended the heavily crevassed Newton Glacier and climbed to Russell Col at the end of the northeast ridge. From there, at about 12,300 feet, the party made the long snow ascent to the summit in a single day, July 31, five weeks after leaving tidewater, and without any technical difficulty.

The expedition occupied a 50-day roundtrip from the coast, mostly spent in bad weather, carrying or hauling loads in deep snow, across and up the glaciers. The duke’s expedition was carefully planned, and he showed himself a capable leader, as well as an experienced mountaineer.

Italian Luigi Amedeo Giuseppe Maria Ferdinando Francesco, also known as the Duke of Abruzzi, was first to summit Mount St. Elias in 1897.

More information about the mountain became known when the matter of the International Boundary between Alaska and Canada became a question of importance after the discovery of gold in the Yukon. Twenty years of continuous survey and field work finally fixed the line.

Northwesterly, the 141st Meridian passed high on the slopes of Mount St. Elias and its survey was carried out under almost insuperable difficulties. An attempted ascent, worthy of permanent record in mountaineering annals, was that headed by Asa C. Baldwin. Unlike the other expeditions that went in from the Pacific side, the Baldwin party attacked inland, going in from McCarthy in the Copper River valley.

“We nearly conquered St. Elias,” wrote a member of the party. “Our goal, the peak of St. Elias, was only 110 miles away in a direct line, but miles became a term totally without meaning. Our route was to be across indescribably rough country … winding always upward, over and around and among vast trackless slopes that were torn and shattered by countless glaciers, which for centuries had crept relentlessly downward toward the sea.

Asa C. Baldwin attempted to climb Mount St. Elias from the Copper River valley side.

“From McCarthy onward, we were to measure distances not by miles but by grueling hours and days and weeks of heartbreaking toil. …”

Their aim was to reach a spot that could by celestial observations be placed on a line through the peaks of St. Elias and distant Mount Cook. There they would build a permanent monument, if possible.

When they reached the 7,000-foot divide between the Columbus and Seward glaciers, they were directly north of the peak. They struck south, then, toward the dome that still towered 11,000 feet above them. They labored up over the increasingly steep ice slope between terrifying walls, until they were about 9,000 feet above sea level. There they had to stop. The slope of ice had reached an angle of 45 degrees and was so rough they could haul the sleds no farther. A tent was pitched:

“We slept little that night. The sudden explosive crash of rupturing ice masses beneath and about us, and the slowly accumulating roar of nearby avalanches kept us constantly tense and fearful. We were pitiably tiny mites in the midst of a cauldron of titanic movement and sound.”

The next morning they gladly pressed on, out of their terrifying gorge – late that afternoon they scrambled onto a shoulder of rock, 14,000 feet above sea level, and made camp. The next morning they started on what they expected to be their final climb – the scramble that would bring them out on the dome that loomed 4,000 feet above them. It was not to be.

“We had considered that we were capable mountain climbers, but we were coming to have a great deal of respect for St. Elias. It wasn’t just another mountain at all. It was St. Elias and it was tough – tough every foot of the way and every second of the time.”

Unnoticed as they worked across dangerous ledges, clouds had been sweeping up the gorge below and behind them. Suddenly the clouds were all about, and the great dome was blotted from sight. Then, without warning, a blizzard was upon them. To stay there was simply to freeze to death in short order, so hour after hour, they worked their way back down the mountainside, half of the time without any hope at all, simply going down to meet death rather than lie down and wait for it.

Between 1912 and 1913, Asa C. Baldwin was the U. S. Chief of Party for the Mount St. Elias to Arctic Ocean 141st Meridian Boundary Demarcation Survey, which included the ascent of St. Elias in 1913. Here at the 1,000 foot level, the glacier is badly shattered.

“All the Gods of Luck must have been clustered about us, guiding our numbed hands and feet, our picks and spikes, for finally we staggered into camp, half frozen and exhausted but all still alive … the lookout at the main camp sighted us as we stumbled down the seemingly endless slope of the Chitina Glacier … a party came up to meet us and helped us into camp.”

And so ended their great adventure on Mount St. Elias — a gigantic mountain, they found, locked in the heart of a vast glacial solitude. Although they had not reached the summit, their efforts had added to the knowledge of the magnificent monument that marks the southwesterly corner of the boundary between Canada and Alaska. First successful American climb

The first American party to conquer the “Saint,” the Harvard Mountaineering Club, included a woman, Betty Kauffman. The party landed at Icy Bay in 1946 and climbed the southwest ridge – more difficult than the duke’s climb, but shorter and more direct.

As Maynard N. Miller, one of the successful climbers, wrote in a National Geographic article:

“The Saint was always trying to throw us off balance, it seemed to me. Across our path it threw yawning crevasses, rumbling avalanches and treacherous ice slicks.”

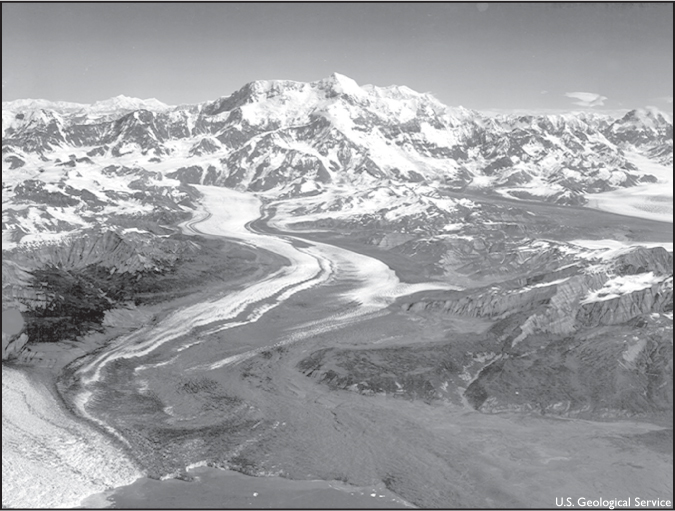

More than three-quarters of their route was over ice and snow, over the unclimbed, broken ice of Tyndall Glacier to the 11,921-foot Mount Hayden, an unclimbed summit whose slopes formed part of their route. From the slopes of Hayden, Miller wrote that they could look across three miles of space to the appalling west face of the “Saint.” They saw blocks of ice, some big as houses, batter into splinters as they bounced down the cliffs.

The mountain waged its war of nerves up to the bitter end, but upward they climbed, over humps, across snow faces, through gullies, from terrace to terrace, chopping, floundering and climbing. Fatigue, headaches and pounding hearts were forgotten when the summit plain – half the size of a football field – was reached.

The first American party to summit Mount St. Elias crossed the Tyndall Glacier, seen here, in 1946.

When she finally reached the summit in 1946, Kauffman had climbed higher than any other woman up to that time in Alaska and Canada.

Dee Molenaar, photographer of the party, beat Kauffman’s husband, Andrew, to the draw when he rewarded Kauffman with a big kiss on the cheek for her accomplishment.

The party unfurled American and Canadian flags over the International Boundary on July 16, which also turned out to be the 205th anniversary of the day Bering’s party had first sighted the snowy peak from 140 miles out to sea and named it for the patron saint of the day, Elias.

The third successful climb added more flags to those two on top of the mountain. This climb was the first by the north route and was made in July 1964. The 20 members of the All Japan-Alaska Expedition included an Anchorage man, Scott Hamilton.

Camp Four was made at 12,800 feet, but the leader of the party was afraid the weather would change and defeat them as it had done so many others, so the two lightest men of the party, Shiro Nishimae and Tokaskio Yaname, were sent in on the final dash that took 37 hours.

“We were so tired,” they said later, “we had to plant the Alaska flag twice. The first time it went in upside down.”

They also planted the flags of the United States, Japan and Canada before leaving the summit on July 17 at 9 p.m.

One year later, the peak was surmounted again, and again by the Harvard Mountaineering Club. This time they climbed the northwest ridge – the first time this route had been successful. The climb took 23 days and was plagued by bad weather. The leader, Boyd N. Everett Jr., was familiar with much of the route, as he had been leader of a 1963 expedition turned back by two earthquakes and several avalanches.

“It snowed 12 of the last 13 days of the expedition,” Everett said of the successful climb. “During the ascent, 57 pitons and 4,900 feet of fixed rope were used – an unusual amount of technical equipment for an Alaskan climb. But this is a very difficult mountain to climb. There’s no easy way up as there is on Mount McKinley. And although it’s the second-highest mountain in the United States, there’s very little known about it.”

Today, Mount St. Elias remains desolate and icebound. It’s still a challenge to explorers and mountaineers and a vast field laboratory for students of glaciers.

Another Alaska mountain also calls climbers to pit their expertise against its treacherous weather and trails – Denali.