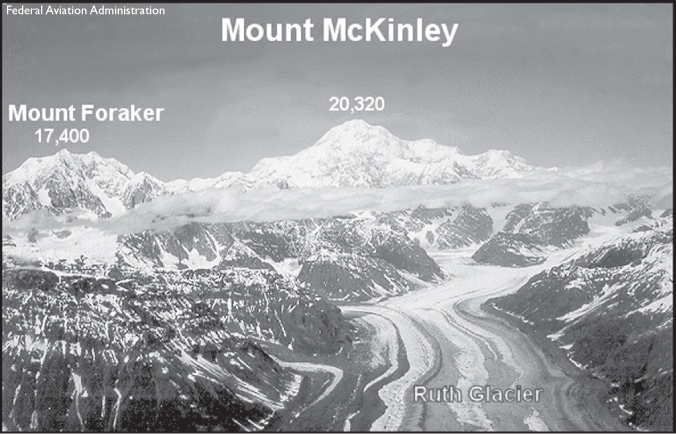

Mount McKinley, also called Denali, in the Alaska Range is the highest peak in North America.

DENALI: THE HIGH ONE

Rising more than 20,000 feet above sea level, a mountain known to early Athabascan Indians of the Interior as Denali, meaning “The High One,” towers over all other peaks in its mountain range.

Mount McKinley, also called Denali, in the Alaska Range is the highest peak in North America.

Generations of Athabascans hunted for caribou, moose and sheep along the lowland hills of the mountain’s northern side. They also picked berries and edible plants and fished in the streams.

The first known mention of the mountain came in 1794 when English explorer Capt. George Vancouver saw what he called “a stupendous snow mountain” from Cook Inlet. Early Russian explorers and traders called the peak Bolshaia Gora, or “Big Mountain,” and in 1889 prospector Frank Densmore referred to Denali as “Densmore’s Mountain” after he hiked within 65 miles of its base.

William A. Dickey, a prospector, named the 20,320-foot mountain – which is said to have one of the earth’s steepest vertical rises – for presidential nominee William McKinley of Ohio in 1896, even though McKinley had no ties to Alaska. Controversy surrounded that name from the get-go and continues today.

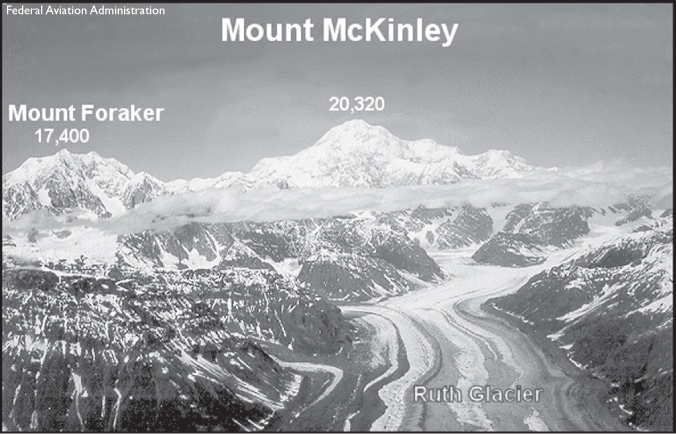

Judge James Wickersham, pictured above, failed in his attempt to climb Mount McKinley in 1903.

The history of climbs on the tallest mountain in North America is as intriguing as its names. And although it can be seen from Cook Inlet on a clear day, its base is deep in the Alaska Range. Explorers in the early 1900s used riverboats, mules and dog sleds to gain access to the mountain’s glaciers in order to establish base camps.

Judge James Wickersham, who’d climbed every major peak of the Olympic Peninsula before coming to Alaska, was the first white man to tackle the mountain. He and four companions made it to about the 10,000-foot level in 1903. Later in life, while delegate to Congress, Wickersham won legislation creating Mount McKinley National Park.

Wickersham, who was the first federal district court judge in the Interior, had recently moved his headquarters from Eagle to the new boomtown of Fairbanks. However, the business of law and order was slow at that time, so “there was time to look around and consider what to do next,” he later wrote in his book, “Old Yukon.”

“To me the most interesting object on the horizon was the massive dome that dominates the valleys of the Tanana, the Yukon and the Kuskokwim,” he said.

He and M.I. Stevens, George A. Jeffery and Johnnie McLeod left Fairbanks on May 16, 1903, heading for the Kantishna River onboard the Tanana Chief. The men had raised money for the adventure by issuing a newspaper and selling advertising. Lacking equipment but swamped with business, Wickersham, who was 45 at the time of the attempt, wrote that the fellows churned out an eight-page Fairbanks Miner “on the first printing press ever brought to the valley – a typewriter.”

Wickersham also printed a notice in the paper that he would be conducting court in the Yukon River village of Rampart on July 27. That gave the expedition about 2-1/2 months to cover around 300 miles.

It took weeks to reach the mountain’s base. The explorers rowed a boat called the Mudlark up the Kantishna and walked mules overland.

“All the tales the Indians told us about snow slides at this season seem to be true, for the whole western face of the mountain, above the glacier, glistens with ice sheets streaked with mineral discolorations from recent slides,” Wickersham noted in his book.

The adventurers climbed the glacier’s central moraine, then up a smaller glacier to the left, which soon rose into a nearly perpendicular icefall that blocked their path. The climbers sat and watched avalanches tumble down the western face, later named the Wickersham Wall.

After hiking back toward Wonder Lake, the party launched a raft in the McKinley River gorge. But it met with disaster after hitting rocks. The men rebuilt the raft, although McLeod refused to ride. He made a canoe from green spruce bark instead. After about a week, they reached Baker Creek, just upstream from Manley Hot Springs on the Tanana River, and hiked 50 miles to Rampart, reaching the Yukon River town on July 7.

This view of Denali from Wonder Lake may have met the eyes of Judge James Wickersham and his party in 1903 as they traveled toward the base of the mountain.

While cleaning up after traveling for two months, Wickersham’s clothes were thrown into the Yukon River by a friend – who also accidentally tossed one of the judge’s prized possessions.

“He stepped gingerly to the bank of the Yukon and threw my castoff clothing, with my hundred-dollar gold watch strongly attached thereto by a moose-hide string, into the river, where they took up their journey seaward!” Wickersham later wrote.

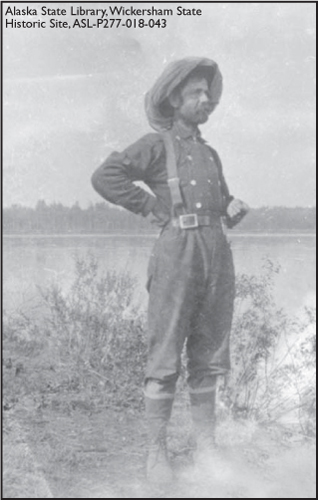

That same year, Dr. Frederick A. Cook and five team members reached the 11,300-foot level. Cook’s team completed the expedition by circumnavigating the mountain, a feat not duplicated until 1995. On the southeastern side, Cook named the Ruth Glacier after his daughter and the Fidele – now called Eldredge – Glacier for his wife.

Dr. Frederick A. Cook

Cook returned to the mountain in 1906, and on Sept. 20, reported that he and Ed Barrill, a hunting guide and blacksmith from Darby, Montana, had reached the summit on Sept. 16.

After returning from Alaska, Cook gave lectures about his achievement – including one in Seattle that started the organization of The Mountaineers. He left his 1903 and 1906 book manuscripts with a publisher in 1907 and then headed for Greenland, a trip that later evolved into an expedition to reach the North Pole.

The following year, Harper’s Monthly Magazine published Cook’s article, “The Conquest of Mount McKinley,” about his journey to the top of the mighty mountain that included photos from the summit and a map of the route taken.

However, his vague description of his ascent route and a questionable summit photo of his guide, Barrill, shown standing on top of an outcropping of rock that was somewhat pointed in appearance, led many to doubt his claim.

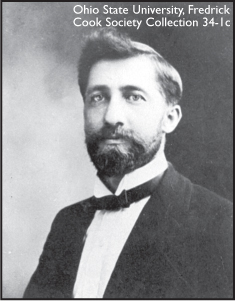

In a speech given to Congress in 1915 by Congressman S.D. Fess of Ohio denouncing another claim by Cook – in which he said he had arrived at the North Pole in 1908, one year prior to Admiral Robert E. Peary – Fess outlined the case against Cook by the Explorers Club and professor Herschal C. Parker of Columbia University. Parker, a partner with Cook in the McKinley expedition, both physically and financially, said Cook’s claim was fraudulent.

Frederick Cook mounted expeditions to Alaska’s Mount McKinley, being the first to circumnavigate it in 1903 and making the first claimed ascent of North America’s highest peak in 1906.

At a dinner sponsored by the National Geographic Society, with a seething Admiral Robert E. Peary in attendance, President Theodore Roosevelt hailed Cook as the conqueror of McKinley and the first American to explore both polar regions.

But critics soon denounced Cook’s claim and suggested his summit photo of Ed Barrill, left, was suspect.

At the time of the 1906 climb, Parker said that Cook assumed the lead with a plan that proved unfeasible, and the party escaped with their lives, thanks to the local knowledge of Belmore Brown, one of its members.

“It was perfectly understood,” said Parker, “that after the misadventure all further attempts were abandoned for the season.”

Otherwise, Parker said, he would not have left the expedition.

Instead of this, Cook, it is charged, sidetracked all members of the expedition until there remained only himself, Barrill and one packer, John Dokkin, a gold prospector, who subsequently turned back because of a fear of glacial crevasses. These defections left Cook no instruments capable of measuring the altitudes he said he attained, according to Parker. Moreover, the summer’s experience had shown that Cook and Barrill were the least physically fit of all the party for arduous mountain climbing.

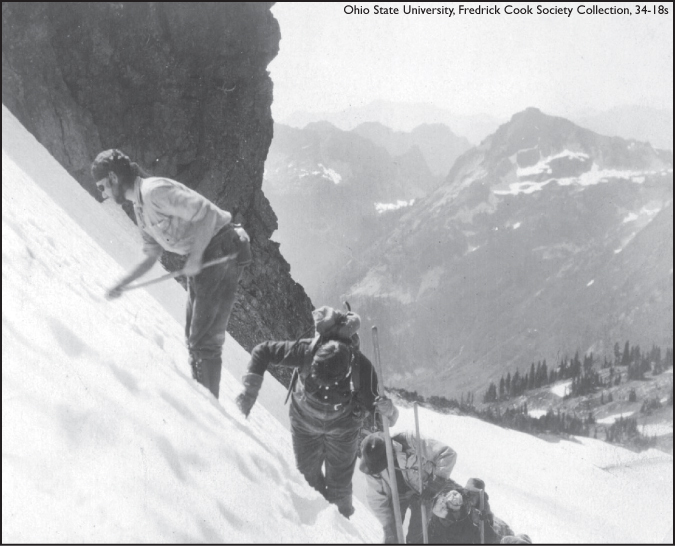

Cook and his expedition work around a glacial crevasse they encountered on their way to summit Mount McKinley.

Brown confirmed Parker’s account. He also added that in Cook’s book there was not one date given from the time he left the Chulitna River, which made intelligent criticism impossible. Brown asserted further that he never saw Cook make a single aneroid barometer reading during the whole trip.

And confirming a charge that had previously been made, Brown said Cook was known to be in serious financial straits and would have had great difficulty in getting out of Alaska if he had not reported that he attained the summit of Mount McKinley.

Brown fortified his charges with the declaration that Cook and Barrill had no ice clamps, and although Cook told Parker later that he and Barrill were roped together every foot of the last stages, Parker and Brown both remembered that they had destroyed the climbing rope before they quit the expedition because it was defective.

Furthermore, no climbing rope appeared in any of the pictures published in Cook’s book. Brown also reported that various photographs in Cook’s book did not represent the peaks they were said to picture.

After Cook returned from the Arctic in 1909, the guide whom he alleged went to the top of Mount McKinley with him announced that they never had been to the summit and that the picture Cook took with Barrill holding a flag on the top was miles from the peak.

Cook asserted that all the allegations and Barrill’s recanting the summit claim were merely part of a plot by Admiral Peary to ruin him.

But based on its investigation into Cook’s claims, the Explorers’ Club ousted Cook from its membership in December 1909. The club concluded in part that:

Some members of Dr. Frederick Cook’s 1906 expedition team carve ice steps out of a steep grade as they climb toward the summit of Mount McKinley.

“Dr. Cook’s account of the ascent is not only such as to be unconvincing to the experienced mountaineer, but that under analysis is incredible. … Cook’s description of the ascent of Mount McKinley on the northeast ridge, which is the ridge by which he claimed to have reached the peak, is in reality, a description of the southeast ridge. The former ridge was explored by him on a previous expedition and in his book he declares it impossible as a route to the peak.”

Wickersham also thought Cook’s claim had no merit. While serving as Alaska’s delegate in Congress, he was asked his opinion of Cook’s claim:

Bradford Washburn, a vocal critic of Frederick Cook, left bits of his equipment behind along McGonagall Pass as he climbed Denali. He was a member of the third expedition to successfully summit and became a well-known expert on the mountain.

“All of us who know anything about Mount McKinley know that Cook’s story of his successful ascent of that mountain is a deliberate falsehood. … His story was so fraudulent, that one does not have time to talk about it.”

There are others, however, who believe that Cook reached the summit, as well as reached the North Pole first, and that claims to the contrary are the result of a character assassination by Admiral Peary and his associates.

While commenting on a book written by Peter Cherici and Bradford Washburn – a noted critic of Cook – titled “The Dishonorable Dr. Cook:Debunking the Notorious McKinley Hoax,” Cook supporter Ted Heckathorn wrote:

“When Dr. Cook returned from his Arctic trip in September 1909, he reported that he had reached the North Pole in April 1908. This quickly developed into a huge media controversy when Robert E. Peary, a U.S. Navy engineer, claimed to be the discoverer of the North Pole in April 1909. Peary could not prove that Cook had not been to the pole in 1908, or that he had been there in 1909, so he instigated a character assassination campaign against Cook.”

Heckathorn and others present more evidence to support Cook’s claim through The Frederick A. Cook Society at www.cookpolar.org.

Cook spent almost half his life surrounded by controversy associated with the Alaska climb and the North Pole expedition. His own words, written in the twilight of an amazing career, may best express the depth of his personal torment, according to the Cook Society:

“… few men in all history … have ever been made to suffer so bitterly and so inexpressibly as I because of the assertion of my achievement.”

A group of men called the Sourdough Party, which included Tom Lloyd, Charles McGonagall, Pete Anderson and Billy Taylor, set out to conquer the mountain in 1910. Bill Sherwonit, author of “To the Top of Denali: Climbing Adventures on North America’s Highest Peak,” wrote that the whole adventure began in a barroom.

“According to Lloyd’s official account of the Sourdough Expedition, which appeared in The New York Times Sunday Magazine on June 5, 1910, ’(bar owner) Bill McPhee and me were talking one day of the possibility of getting to the summit of Mount McKinley and I said I thought if anyone could make the climb there were several pioneers of my acquaintance who could. Bill said he didn’t believe that any living man could make the ascent.’

“McPhee argued that the 50-year-old Lloyd was too old and overweight for such an undertaking, to which the miner responded that ‘for two cents’ he’d show it could be done. To call Lloyd’s bluff, McPhee offered to pay $500 to anyone who would climb McKinley and ‘prove whether that fellow Cook made the climb or not.’ After two other businessmen agreed to put up $500 each, Lloyd accepted the challenge.

The Sourdough Expedition to climb Denali started out as a barroom bet when Fairbanks, pictured above, was a gold-rush boomtown at the turn-of-the-last century.

“The proposed expedition was big news in Fairbanks, and before long it made local headlines. In his official account, Lloyd admitted, ‘Of course, after the papers got hold of the story, we hated the idea of ever coming back here defeated.’”

The expedition set off in February and only carried bare essentials, according to Sherwonit, including: “… snowshoes; homemade crampons, which they called creepers; and crude ice axes, which Lloyd described as ‘long poles with double hooks on one end — hooks made of steel — and a sharp steel point on the other end.’

“Their high-altitude food supplies included bacon, beans, flour, sugar, dried fruits, butter, coffee, hot chocolate, and caribou meat. To endure the subzero cold, they simply wore bib overalls, long underwear, shirts, parkas, mittens, shoepacs (insulated rubber boots), and Indian moccasins. (The moccasins that the pioneer McKinley climbers wore were like Eskimo mukluks: tall, above-thecalf footwear, dry-tanned, with a moose-hide sole and caribou-skin uppers. Worn with insoles and at least three pairs of wool socks, they were reportedly very warm and provided plenty of support.)

“Even their reading material was limited. The climbers brought only one magazine, which they read from end to end. ‘I don’t remember the name of the magazine,’ Lloyd later commented, ‘but in our estimation it is the best magazine published in the world. …’”

After about two months of hiking, the men finally hauled a 14-foot spruce pole and a 6-foot by 12-foot American flag to the top of the North Peak, which people of the time thought was the highest point.

The climbers thought that the flag would be seen from Kantishna, the mining community north of the mountain, and would serve as visible proof of their conquest, according to Sherwonit.

Taylor and Anderson made their summit push from 11,000 feet, and hauling their flagpole, they climbed more than 8,000 vertical feet and then descended to camp in 18 hours’ time on April 3.

The members of the Sourdough Expedition wore Indian moccasins, or mukluks, on their trek up Denali. Mukluks proved to be suitable gear for the U.S. Army, as well. This cart load contains 780 pairs headed to soldiers in Nome in the early 1900s.

“… an outstanding feat by any mountaineering standard,” wrote Sherwonit, who added, that by comparison, most present-day Denali expeditions climb no more than 3,000 to 4,000 vertical feet on summit day, which typically lasts 10 to 15 hours.

However, upon reaching the North Peak, the party discovered that the South Peak is in fact higher by 850 feet. The Sourdough Party planted the flag, but since it could not be seen from the north, the climbers only had their word as proof of their claim.

The first complete and well-documented ascent of the true summit of Denali was made on June 7, 1913, by a determined, but less than professional, party.

The Rev. Hudson Stuck, Episcopal archdeacon of the Yukon, was an experienced climber and northern traveler but had never tackled anything comparable to Denali. However, he was certain that Cook’s claim of reaching the summit of the mighty mountain was false and had even made a bet with a friend that Cook’s 1906 attempt would fail.

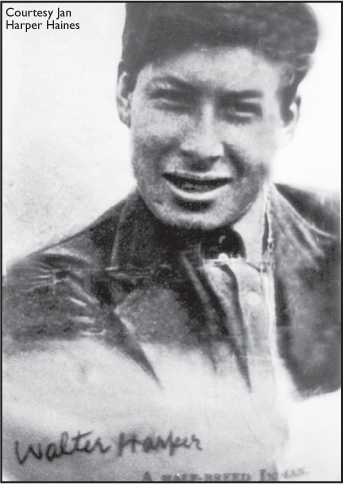

Stuck set out with Robert Tatum, his young assistant; Harry Karstens, an experienced northern outdoorsman; Johnny and Esaias, two Indian boys aged 14 and 15, and Walter Harper, a 21-year-old half-Athabascan and half-Irish fellow who was Stuck’s student, guide, interpreter and dog team handler at the time. Harper became the first person to set foot on the higher South Peak.

The story of the team’s achievement was recorded in Stuck’s book, “The Ascent of Denali.” And out of respect for the Native people among whom he lived and worked, Stuck, who was 50 at the time of the historic climb, refused to refer to the mountain as McKinley and states in the preface of his book: “Forefront in this book, because forefront in the author’s heart and desire, must stand a plea for the restoration to the greatest mountain in North America of its immemorial native name.”

Stuck and his party of Alaskans struggled for three months on foot from Nenana as they forded rivers, hiked through dense forest and upland tundra and climbed up glaciers and ridges to their objective. When the group finally came upon the base of the great mountain, Stuck noted:

“On the 11th April Karstens and I wound our way up the narrow, steep defile for about three miles from the base camp and came to our first sight of the Muldrow Glacier. … There the glacier stretched away, broad and level – the road to the heart of the mountain, and as our eyes traced its course our spirits leaped up that at last we were entered upon our real task. One of us, at least, knew something of the dangers and difficulties its apparently smooth surface concealed, yet to both of us it had an infinite attractiveness, for it was the highway of desire.”

Archdeacon Hudson Stuck’s party, pictured above, included six men and two dog teams. The group started from Nenana to ascend Denali.

After losing their tent and many belongings in a fire at 8,000 feet, the men sewed a tent from old sled tarpaulins and continued to the summit.

“The last thing a newcomer would dream of would be danger from fire on a glacier, but we were not newcomers, and we all knew how ever-present that danger is, more imminent in Alaska in winter than in summer,” Stuck wrote. “Our carelessness had brought us nigh to the ruining of the whole expedition. The loss of the films was especially unfortunate, for we were thus reduced to Walter’s small camera with a common lens and the six or eight spools of film he had for it.”

As they climbed higher and higher, Stuck recorded his thoughts on the sights that unfolded before him.

“Above us the sky took a blue so deep that none of us had ever gazed upon a midday sky like it before. It was a deep, rich, lustrous, transparent blue, as dark as a Prussian blue, but intensely blue; a hue so strange, so increasingly impressive, that to one at least it ‘seemed like special news of God,’ as a new poet sings. We first noticed the darkening tint of the upper sky in the Grand Basin (located between the North and South peaks), and it deepened as we rose. Tyndall observed and discussed this phenomenon in the Alps, but it seems scarcely to have been mentioned since.”

The climbers also made a noteworthy discovery while in the Grand Basin. They spotted the Sourdough Party’s flagpole.

“While we were resting … we fell to talking about the pioneer climbers of this mountain who claimed to have set a flagstaff near the summit of the North Peak – as to which feat a great deal of incredulity existed in Alaska for several reasons – and we renewed our determination that if the weather permitted when we had reached our goal and ascended the South Peak, we would climb the North Peak also to seek for traces of this earlier exploit on Denali. … All at once Walter (Harper) cried out: ‘I see the flagstaff!’” Stuck wrote.

“Eagerly pointing to the rocky prominence nearest the summit – the summit itself covered with snow – he added: ‘I see it plainly!’ (Harry) Karstens, looking where he pointed, saw it also and, whipping out the field glasses, one by one we all looked, and saw it distinctly standing out against the sky. With the naked eye I was never able to see it unmistakably, but through the glasses it stood out, sturdy and strong, one side covered with crusted snow. We were greatly rejoiced that we could carry down positive confirmation of this matter.”

Athabascan Walter Harper, son of pioneer Arthur Harper, was the first person to summit Denali.

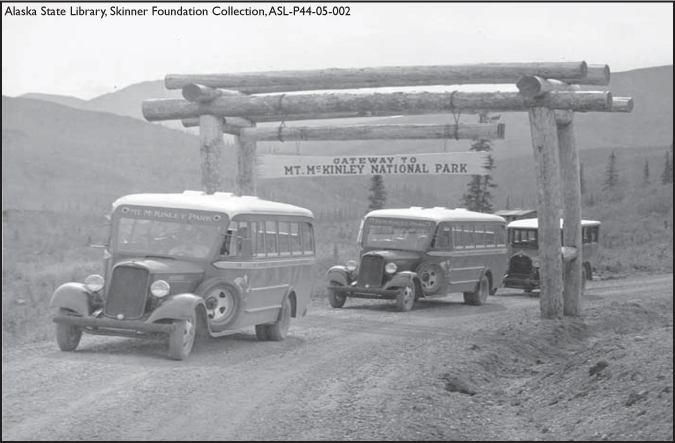

After the Stuck party successfully climbed to the summit of Denali, others attempted the feat. The photo above shows a pack train operated by Dan T. Kennedy heading into then-McKinley National Park in the 1920s.

Stuck’s group finally made their summit of the South Peak on June 7, 1913. The good Archdeacon wrote:

“Across the gulf, about three thousand feet beneath us and 15 or 20 miles away, sprang most splendidly into view the great mass of Denali’s Wife, or Mount Foraker, as some white men misname her. Denali’s Wife does not appear at all save from the actual summit of Denali, for she is completely hidden … until the moment when (it) is surmounted. And never was (a) nobler sight displayed to man than that great, isolated mountain spread out completely … beneath us.”

The sight of Denali’s Wife confirmed in Stuck’s mind that Cook had never reached the summit of Denali.

“(Cook) does not mention at all the master sight that bursts upon the eye when the summit is actually gained – the great mass of Denali’s Wife … filling the middle distance. We were all agreed that no one who had ever stood on the top of Denali … could fail to mention the splendid sight of this great mountain.”

Piloted by Joe Crosson, the first airplane landed on the mountain in 1932. Today, more than 1,000 people attempt to climb Denali each year between April and June, most flying in to base camp at 7,200 feet on Kahiltna Glacier.

Geographic features of Denali and its sister peaks bear the names of early explorers: Eldridge and Muldrow glaciers, after George Eldridge and Robert Muldrow of the U.S. Geographic Service who determined the peak’s altitude in 1898; Wickersham Wall; Karsten’s Ridge; Harper Icefall; and Mount Carpe and Mount Koven, named for Allen Carpe and Theodore Koven, both killed in a 1932 climb.

In 1980, the name Mount McKinley National Park was officially changed to Denali National Park and Preserve. The state of Alaska Board of Geographic Names also has officially changed the mountain’s name back to Denali. Negotiations continue to officially return the original Native name to the magnificent mountain.

Two buses and one automobile drive under a sign to Mount McKinley National Park around 1925.