Mount Katmai erupted in Southwest Alaska during the summer of 1912.

KATMAI ERUPTS

On June 6, 1912, the earth exploded. People living within a radius of several hundred miles in Southwest Alaska were given a taste of what hellfire and brimstone of Biblical teachings might be like.

It all began in a beautiful, broad valley about 100 miles west of Kodiak Island that was just turning green after a long winter. Dense balsam poplar, paper birch and occasional clumps of spruce covered the hills up to nearly 1,500 feet. Herds of caribou, a few moose and great, brown bears foraged for food. Packs of hungry wolves and skulking wolverine hunted for game to satisfy their hunger, and in the Ukak River, fish splashed. It was a scene of peace and tranquility.

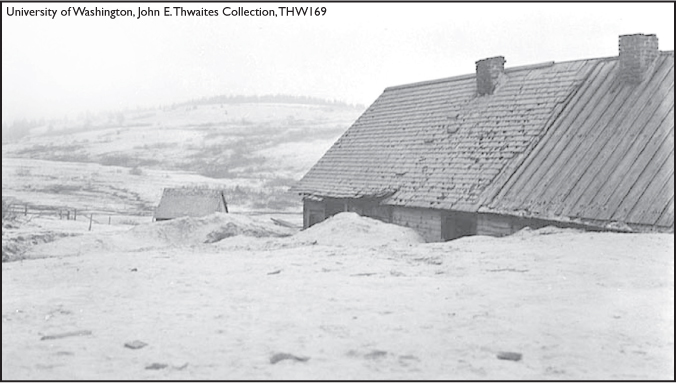

Mount Katmai erupted in Southwest Alaska during the summer of 1912.

Eskimos traveled along this route across the Alaska Peninsula, and later, Russians went through it journeying from their Kodiak Island settlement to the Bering Sea. During the gold rush at Nome, a few stampeders trudged through Katmai Pass on their way to the Seward Peninsula. There were only a few Native villages in the area, including Katmai village close by Shelikof Strait, and Savonoski, Ukak and another village near the head of Naknek Lake.

It was very fortunate so few people lived there. Most authorities say no lives were lost in Katmai’s eruption, although Merle Colby claims about 200 Natives in remote villages in the path of the ash fall died. If the cataclysm had occurred near a more densely populated region, a great number of lives could have been lost. A similar explosion at Mount Pelee on the Caribbean Island of Martinique killed 30,000 people on May 8, 1902.

The Natives of Savonoski and Katmai were the only eyewitnesses to the most spectacular volcanic eruption to occur in North America. In the words of American Pete, Savonoski’s village chief:

“The Katmai Mountain blew up with lots of fire, and fire came down trail from Katmai, with lots of smoke. We go fast Savonoski. Everybody get in bidarka (Native boat). Helluva job. We come Naknek one day, down river, dark, no could see. Hot ash fall. Work like hell.”

Of those nearest the volcano, all but six of the inhabitants of Katmai village had gone fishing at Kaflia Bay. The two families left at the village became frightened by the earthquakes that preceded the eruption and fled. They still were camped along the coast near Cape Kabugakli, within sight of Katmai, when the mountain blew up.

They then hurried to Cold Bay, and their accounts of the incident were transcribed in the diaries of two white men living there.

“Two families arrived from Katmai, scared and hungry, and reported the volcano blew up 15 miles from Katmai (village), to the left of the Toscar Trail and that one-half the hill blew up and covered up everything as far as they could see,” wrote C.L. Boudry on June 8. “Also, that small rocks were falling for three or four miles at sea but could not see more of it as everything else closed up with smoke. …”

Native residents of a Katmai village found their barabaras – Native dwellings – buried in ash from the 1912 eruption of Mount Katmai.

The other man, Jack Lee, wrote in his diary:

“They reported the top of Katmai Mountain blun (sic) off. There was a lot of pummy stone in their dory when they got here and they say hot rocks was flying all around them.”

The only other people anywhere near the volcano were the Natives at the fishing station at Kaflia Bay, about 30 miles from the crater and screened from the volcano by intervening mountains. Their ordeal was terrifying, nevertheless, as testified by a letter written by Ivan Orloff at the fishing camp to his wife on June 9.

“… I do not know whether we shall be either alive or well. We are awaiting death at any moment … a mountain has burst near here so we are covered with ashes in some places 10 feet and 6 feet deep. … We cannot see the daylight. All the rivers are covered with ashes. Here are darkness and hell, thunder and noise. I do not know whether it is day or night … pray for us.”

These fragmentary statements contain all the testimony available from points within 30 miles of the explosion, but reports came from many other places, too.

D.F. Howard, camped on the west shore of Cook Inlet, said he saw Katmai blow.

“The day was exceptionally clear, and I had a view down the Inlet for 130 miles. Early in the afternoon, I heard a series of heavy explosions … increased until it resembled the continuous roar of a heavy canon barrage.”

He said he looked toward Mount Iliamna, and to the left and far beyond, and he could see two columns of volcanic matter shooting skyward with incessant flashes of lightning darting in every direction.

Next day, he could not tell when the sun arose. Visibility was obscured beyond a distance of 150 feet. Even when the air cleared on June 9, and an unobstructed view of the Inlet was obtained, it was impossible to determine the eruption’s origin.

The Dora, the intrepid little mail boat that had had a share in almost every adventure in Southwest Alaska, brought the first news of the eruption to the outside world. And her captain, C.B. McMullen, located the seat of the eruption.

On June 6, the Dora was sailing into Kupreanof Strait between Kodiak and Afognak islands when crewmembers noticed a huge, dense cloud rise over Mount Katmai. It spread northwestward over the sky and masses of volcanic ash settled over the sea. It became so dense the captain had to bypass Kodiak.

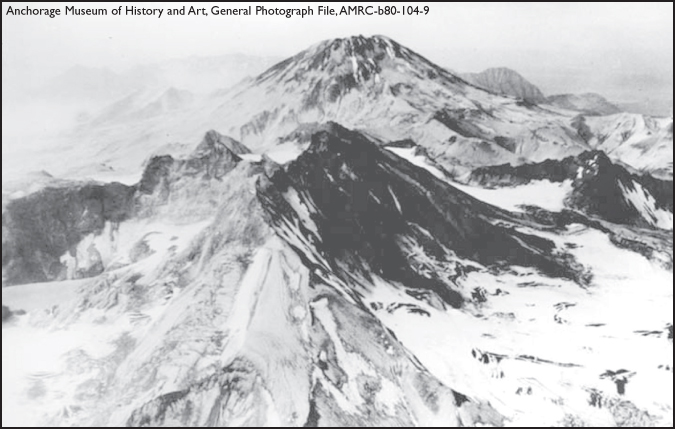

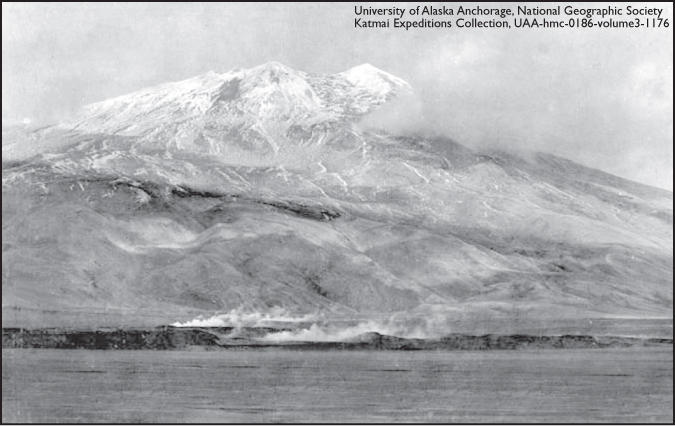

View of Katmai crater during an eruption in 1913.

After passing through the largest volcanic eruption in North America in the last century, mail carrier Dora arrives near Kodiak Island in 1912.

The clerk on the mail ship vividly described their experience as the ship crossed the area of falling ash.

“… lurid flashes of lightning glared continually around the ship while a constant boom of thunder increased the horror of the inferno raging around us … we might as well have been miles above the surface of the water … birds floundered, crying wildly through space and fell helpless to the deck.”

Before the Dora brought the news of the eruption to Seward, none of that town’s residents knew what had happened.

“On June 7, the people of Seward heard a series of explosions that sounded like heavy blasting,” Mel Horner later remembered. “High overhead a tremendous mist like a cloud formed, blotting out the brightness of the sun and turned it copper-colored. For the following three days, the cloud hung over the city, gradually settling closer and closer to the earth, and the buildings, yards and streets were covered with a fine layer of ash. Lawns were killed and the fresh shoots of trees leafing out, also.”

A news dispatch from Cordova, 360 miles northeast of the eruption, reported that many people received painful burns when a heavy rain mixed with the ash in the air to form sulfuric acid. At LaTouche, also in Prince William Sound, the rain was so acidified by the fumes it caused serious burns wherever it touched flesh. The extreme limit of the fumes was much more distant for they were reported from several places in Washington state and British Columbia, about 1,500 miles from the scene of the eruption.

However, the Alaska community that underwent the most terrifying experience was much nearer — the closest sizable town, Kodiak, was 120 miles away. Terror and fear held the island’s 400 inhabitants in a grip of smothering ashes and volcanic fumes for days.

None of the people who went through those days fail to mention the awful darkness, which was described as something so far beyond the darkness of the blackest night that it cannot be comprehended by those who did not experience it.

Through some freak of sound transmission, most of the people in Kodiak did not hear the explosions at all. Their first warning was a peculiar-looking, fan-shaped cloud, blacker and denser than any cloud ever seen before. Flashes of lightning flickered through the cloud, thoroughly alarming the people since electrical storms are rare at Kodiak.

By 5 p.m., a light ash began to fall and by 8 p.m. it was dark. The ash fell so heavily that people were afraid they would suffocate. As it drifted through the doors and sifted through the windows, Kodiak islanders remembered the fate of the people of Pompeii, and they began to fear that they, too, would be buried alive. The ash drifted, swirled and eddied — it filled the nostrils and stung the eyes. All that first night of horror the noise, gas, earth shocks, lightning and thunder continued.

A brief respite came on June 7, in the morning, and then it started again. The density of the ash flow was incredible. So thick was the air with ashes, that when a log building burned to the ground, people 200 feet away were unaware.

Fortunately for the people of Kodiak, the Revenue Cutter Manning was in the harbor at the time, and the priest of the Greek Orthodox Church told his people that if the church bells began to ring they were to go down to the dock where the Manning was berthed.

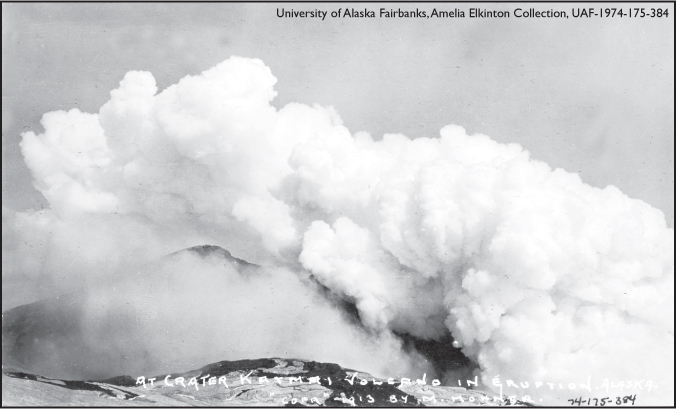

A person in Kodiak stands on the roof, on the right side of the photo, of a building partially buried in volcanic ash from the Katmai eruption.

Ash-covered buildings around Kodiak during the eruption of Katmai in 1912 fill the landscape. About 46,000 square miles of the area surrounding Katmai was covered in more than .40 inch of ash.

About 4 a.m. on the morning of June 8 the church bells began to chime and the ship’s whistle blew blast after blast. People tied dampened cloths over their faces and groped their way along fences and through drifted banks of ash to seek refuge. It was the longest walk they ever took, according to people who went through the experience.

The captain of the Manning finally decided not to stay in port, as it could mean death to all. There might be chance for life if the ship could get out to the open sea. The Manning first anchored off Woody Island, however, where its 103 inhabitants were brought to the boat. Many of them were nearly starving for food and water.

More than 500 people jammed aboard the vessel, which was incapable of accommodating one-forth that number. It was standing room only on the crowded decks. During the night of June 8, ash began falling again — the fourth layer of ash. Before the air finally cleared after this last fall, Kodiak had experienced two days and three nights of practically unbroken darkness.

U.S. Revenue Cutter Manning, seen here in Seward between 1904-1913, carried more than 500 residents of Kodiak and Woody Island to safe waters during the eruption of Mount Katmai in 1912.

When the morning of June 9 finally dawned, clear and bright, the people began to murmur about going home.

From the decks of the Manning on June 10, the Kodiak people saw their town still there, but dead. Ashes covered the town and buildings like a blanket of snow. Like snow, too, it had drifted up to the eaves in some buildings. Roofs were caved in and fences lost. Cows wandered aimlessly, or stood still with heads hunched down.

It was even more desolate in the once-beautiful valley of Katmai, however.

A year later, William Hesse, U.S. Deputy Land and Mining surveyor, and Mel Horner of Seward were the first into Katmai after the eruption. Part of their trail took them through what had once been a heavily wooded area. Nothing remained but a few dead, misshapen trunks and limbs of cottonwood and spruce. Pumice floated on the small steams up to a foot thick.

When they finally arrived at the scene of the volcanic eruption, they found a huge area of mountainside blown out of Mount Martin, one of the peaks in the area. Fragments, some as large as box cars, had been hurled out, or massed on top of one another, as far as half a mile. The fertile valley that once had been the home of otter, mink, ermine, fox, bear, caribou and moose, was now barren and lifeless, except for one mangy fox, thin as a pile of bones. A few bears they later found had survived, but acid had burned great holes in their fur.

Thousands of small fumaroles issued columns of steam and smoke, and the ground was a maze of wide, jagged cracks like paths of lightning. The land lay denuded of timber — only blackened stumps were left.

The man who made the Valley of 10,000 Smokes known to the world, Robert F. Griggs, arrived on the scene three years after the eruption, and to him we owe much of our knowledge of the event that produced, as he said, “… one of the great wonders of the world.”

Griggs’ summary of events stated there were first premonitory symptoms, especially earthquakes, sufficient to warn the Natives. Early in June, rock started falling from Falling Mountain. Next, great hot sand flow came from fissures in the valley and its branches, covering 53 square miles to an estimated average depth of 100 feet.

After two weeks, the volcanic ash from the Katmai eruption measured 10-1/2 inches deep. Note the three different layers that became settled and packed by rains.

The “Smokes of the Valley” began their operation, perhaps coincident with the sand flow.

Explosive activity next began at Novarupta, when about one-half of a cubic mile of coarse pumice was thrown out over an area 10 to 15 miles in diameter, overlapping with the explosion of Katmai. Martin and Mageik may have opened next, according to Griggs, and then could have come landslides.

The first major explosions of Mount Katmai occurred on June 6 at 1 p.m., and they were responsible for the first layer of gray ash. The second major explosion came at 11 p.m., creating the second layer of ash (terracotta).

On June 7, at 10:40 p.m., the third major explosion erupted and brought a yellow layer of ash. Cap layers of fine, red mud were thrown out by Katmai, and next may have been the Katmai Mud Flow.

Then came a condition of great, but gradually subsiding, activity and the interior of the crater retained an incandescent heat manifesting red reflections on the clouds as late as July 21. The end of the explosive stage finally came, followed by a quiet evolution of vapor in great quantity from Katmai, Martin, Mageik, Trident and the Valley.

Although early National Geographic expeditions found Katmai decapitated and assumed it had blown its top, Dr. Garniss H. Curtis, professor of geology at the University of California, believed that Novarupta, a new volcano six miles away, felled its giant neighbor by siphoning off its underlying magma. Measuring each layer of ejected material, Curtis observed that all activity centered around Novarupta; the layers became thinner as they neared Katmai. Novarupta subsided after hurling more than seven cubic miles of pumice, rhyolite and dust, some soaring well into the stratosphere, according to Curtis.

Whether it was Katmai or Novarupta, the results of the cataclysm was tremendous. According to Griggs, more than 40 times the amount of material dug in the greatest excavation ever attempted by man — the Panama Canal — was thrown into the air. All the buildings of all the boroughs of greater New York City wouldn’t fill Katmai’s crater. In fact, the buildings of 15 major U.S. cities would be less bulky than the material blown off the mountain.

This chunk of pumice was thrown out from Novarupta.The pickaxe next to it shows the scale of the rock’s size.

B.B. Fulton, Robert F. Griggs and L.G. Folsom in 1915 cook over a fire at their base camp in what is now Katmai National Park and Preserve.

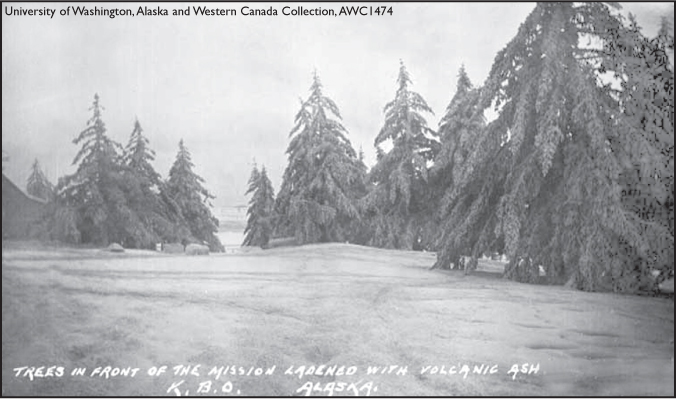

The 1912 eruption of Mount Katmai was the largest in North America in the 20th century. It covered 46,000 square miles of area with ash. The photo below shows trees covered in ash near the Russian Orthodox Church mission house where members of the 1913 expedition stayed while in Kodiak.

No eruption since records were kept has produced so striking an irregularity in the temperature curve as this one, Griggs said. It made the summer of 1912 cooler than usual in the northern hemisphere, the haze absorbing some of the sun’s heat; low temperature persisted generally in low latitudes during the remainder of 1912 and through the summer of 1913. It darkened the days and created brilliant sunsets as far away as Nova Scotia, across the North American continent.

In the summer of 1962, Ernest Gruening reported in an article in the National Geographic that he finally stood in the Valley of 10,000 Smokes.

“We go back a full half-century together. Word of the volcanic cataclysm reached the United States slowly,” he wrote. “In Boston, where I was working as a newspaperman, the news was not received until three days after the event. It came from Cordova — 360 miles from the eruption — and gave few details.”

Now he saw for himself the results.

“The trees were silvered skeletons, bleached sentinels in a shimmering desert of pumice. It is a pastel wasteland like no other, a vast solitude of mountains and desert and desolation; a land of snowfields and glaciers and airy pumice stones and deep crevices … had I not known where I was, I’d have thought it was the moon.”

Indeed, a few years later, some of the astronauts were taken to the region to train for their forthcoming trip to the moon.

The eruption of Katmai had created this wonderland, set aside by President Woodrow Wilson, as a great national monument to nature’s awesome power … the largest national monument in the United States.

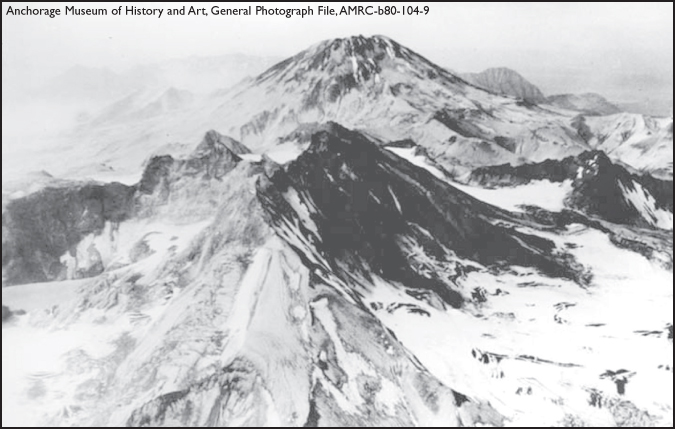

Knife Peak rises near the Valley of 10,000 Smokes in 1917. It was later renamed Mount Griggs for Dr. Robert Fisk Griggs (1881-1962), a botanist, whose explorations of the area, after the eruption of Mount Katmai in 1912, led to the creation of Katmai National Monument by President Woodrow Wilson in 1918. The photo was taken at what was later designated as Katmai National Park and Preserve, during a National Geographic Society expedition to Katmai area.