THE GHOST OF IRA HAYES

“JESSICA?”

“Yeah?”

“Why do you stay with me?”

Jess and I lay on my mother’s wraparound couch. We’re both curled up under blankets, our heads meeting in the middle of the couch’s U. The lights are off, but I can still see her face clearly. Our noses are only inches apart.

“Why do I stay with you? Why do you stay with me? Haven’t I done enough damage, too?”

“No fair. You go first.”

She smiles and shakes her head. “Always so damn stubborn.”

“I’m a Marine.”

“I know, I know.”

She reaches up and runs her fingers through my hair. I’ve been away from Parris Island, so I’ve let it grow out a little. A little meaning about an inch, anyway.

“Come on, after last night, you’ve got to be wondering the same thing,” I coax.

“I don’t know … I’ve loved you since I was fifteen years old. Isn’t that enough?”

“We have been together a long time,” I muse.

“Ever since my dream.”

God, I had forgotten about that. When I was a junior, Jess was a freshman. She had been in the stands the night I got hurt and was carried off the field with my knee injury. One day. while trying to maneuver around the campus on crutches, I noticed her at her locker. Mine was not far away. I couldn’t help but stare at her. She was so beautiful and fresh-faced, I couldn’t tear my eyes away.

Her friends noticed. A few days of this and one of them came up to me and said, “Hey, Jessica had a dream about you the other night.”

Boldness was never a problem for me. Later that day, I walked right up to her as she busily stuffed some books into her locker and said, “Hey, heard you had a dream about me.”

All of fifteen. She flushed red and could hardly speak, and her reaction told me everything I needed to know. She felt the connection, too. We had something before we even said hello to each other.

“Say, what was that dream anyway?” I ask. It dawned on me I never bothered to find out.

Jess smiles. “I’ve been waiting for you to ask that. Took you long enough.”

“Sorry.”

“We were in a car coming back from Prospect after going out for ice cream.”

Her words are a blow. Prospect was the next town over. As small as Richwood, its only attraction was a little ice cream shop downtown.

“We did that!”

“Yes we did,” she agrees.

Her dream was a prophecy. It led us to this moment.

“It all started so well, Jess. And it all fell apart.”

“Yeah. It did, but when we’re good, we’re great, you know?” She thinks for a moment, then adds, “We’re comfortable together.”

“We drive each other crazy,” I say.

“Well, it hasn’t been good. Doesn’t mean it can’t be.”

I roll over on my back and look up at her. She lays her head against mine.

“I just want you to get better.”

True confessions time, Jeremiah. There’s no sense in hiding or lying to anyone anymore.

“I don’t know how,” I tell her.

“I know, but we’ll figure it out, okay?”

“Tonight, the chaplain said something to me. …” I begin, but then my voice stalls and I fall silent.

After the Denny’s intervention moment, my mother drove me over to Marion General Hospital. A nurse took my vitals, then left us alone in a room in the ER. I had expected rubber walls and a straitjacket after everything Von had told me, but it didn’t work out that way. Instead of a shrink, a chaplain my mom knew came by to talk to me. At that point, I was beyond caring who knew how far I’d fallen. When he asked me how I was doing, I said, “I’m twenty-three years old and totally satisfied with everything I’ve done in my life. I feel like there’s no need to keep going.”

My mother didn’t like that at all.

“What did he say to you?” Jessica asks.

“I guess he works with the local police department. He says he sees a lot of cops who’ve lost their faith in life. You know, they show up on some call and the scene’s pretty horrific. That affects a guy. The chaplain told me some stories that made me realize that there are a hell of a lot of people in my shoes, and they somehow get out of bed and get through the day.”

“Did it help knowing that?”

“I suppose I already knew that. After that group therapy session and all. …”

“What group session?” I’d forgotten I hadn’t told her about that. Come to think of it, I haven’t told her much about anything this past year. I tell her about it, and she grows very still next to me. The idea that so many people suffer from PTSD is a new concept for her. Hell, it is for me, too, really.

Cops. Veterans. Firefighters. The chaplain connected the dots for me. No wonder the divorce rate is so high in all three professions.

“Did he tell you what to do?” Jess asks.

“No. When we finished talking, he asked me if I planned to hurt myself after I got home.”

“How’d you answer?”

“I told him no.” What I didn’t tell him was I had no intention of dying—at least, no conscious intent.

Jess rolls on her stomach and puts her lips against my ear. “Jeremiah, tell me how I can make things better for you.”

“Bring back Raleigh, Eric, and James,” I say without thinking.

She starts to cry softly in my ear. “I can’t do that. And I can’t undo what I did. All I can do is tell you how sorry I am.”

“I can’t undo anything either, Jess. But sometimes I wonder if we’ve done too much damage to each other, you know?”

She doesn’t answer.

“We’ve hurt each other a lot.”

“Just tell me how I can make it better,” she says again.

“I don’t know. I’m in a dark place right now. But I want to get out of it.”

“Does getting out include me?” she asks, her voice wavering.

“You know, all I ever wanted was somebody who would love me.”

I feel her hand slide across my cheek. She cups my chin, her upside-down face appears over mine, and she kisses me. I cradle her neck with my right hand and kiss her back.

That’s the other thing that’s kept us together: The chemistry is unreal.

“I love you,” she says as she moves back and rests her head next to mine again.

“I love you, too. But I feel like I’m betraying myself for doing it.”

“I know. My husband tried to kill himself last night, and all I kept thinking was this was my fault. I drove you to it.”

“That’s not true.”

“Tell me that again,” she whispers.

“It isn’t. You need to know what it’s like for me now.”

“What do you mean?”

I rise up on my elbow and face her. Her eyes are wet with tears. “It doesn’t matter where I am or what I’m doing, I see Raleigh, James, and Eric every moment, like they’re overlayed on my life today, you know?”

She shakes her head slightly.

“Right now, I blink, and I’m back on a 998 Humvee, looking down at them.”

“Jeremiah …”

“No, you need to know this,” I insist.

“They are with me every second. It’s like my mind’s a broken record and the needle’s stuck right there on December 23rd, about lunchtime. Over and over, I see it. I can be eating breakfast, and I see them. Driving.

I see them. Working, trying to sleep. They are always there. And I always feel the same thing.”

“What?”

“Shame. Guilt. Horror.”

“What can I do? Jeremiah, please, tell me there’s something.”

“Jessica, I don’t know what anyone can do. I’m at war with my own mind, you know? If you and your dad hadn’t stopped me, I would’ve been another casualty of Fallujah. The insurgents would’ve won after all, like an eight-thousand-mile sniper shot.”

“Isn’t that reason enough to live? To keep them from winning?”

That hits home. “Yes,” I say after a long, thoughtful pause.

“What about the future? What do you want?” she asks.

I slip back down onto the couch on my back and stare at the ceiling. “The future? Jess, I’m just trying to make it through the day.”

“Jeremiah, don’t you want a family?”

“Yeah. But come on, what kind of father can I be now?”

“Not now, but in time when we’re ready,” she says.

“Will we ever be? Jess, I haven’t exactly had the best role models for fatherhood, you know? Where would I even start?”

“Start with what’s inside you. I know you’re a good man. I’ve seen that in you.”

“The things I’ve done …”

“Shhhh. You’re not going there. Neither of us are. Not tonight, okay?”

“Okay,” I agree.

We lie in silence for a long moment. I feel her cheek pressed to mine, eyes side by side. It is so intimate, yet I feel so lost. I have no idea what to do.

“Remember when you first came home?” she asks.

“Yeah.”

That was an amazing, confusing day. We’d all been so excited when we boarded the plane in Kuwait. But the closer we got to the States, the more nervous I became. Jess and I hadn’t communicated much, especially after the 23rd of December. We had about a month to go in that country, and I sent her an email and we reconnected. Can you imagine that? A husband in Iraq having to reconnect with his own wife?

“I knew right away that you’d changed. I didn’t know how, but I thought I knew why.”

By the time we landed in California, I was so nervous I wanted to go back to Iraq. Looking around at the other men in my platoon, I sensed some of them felt the same way.

“How had I changed?”

They bussed us to our own private corner of Camp Pendleton. Fire trucks sprayed out arcs of water over our path, like aquatic crossed swords. Banners flew. Hundreds of people lined our route holding signs and waving furiously. The guys on the bus with me would shout out, “Hey! There’s my wife!” or “There’s my folks!” as they pinpointed their loved ones in the crowd. We sang “Ninety-nine Bottles of Beer on the Wall” and sucked on orange slices and tried not to explode with anticipation. Or nerves.

One big sign read, WEAPON’S CO.: THIS WAY TO HOT CHICKS AND

BEER?.

“Remember that old movie, Crocodile Dundee?”

“Yeah.”

“Remember when Paul Hogan goes to New York?”

“Okay,” I say.

“You were like that.”

“What do you mean?”

“Oh come on. You sat on the bed and stared at the television like you’d never seen one before. Then you sat and watched all the traffic.”

“Yeah, I was amazed nobody was getting blown up.”

“No, it was like you had come from a primitive country and had never seen all this stuff we have here.”

She nailed it. I spent thirty minutes in the bathroom just flushing the toilet, amazed to see running water again. “Reverse culture shock, I guess. But how’d that make me different?”

“I don’t know. I just sensed a sea change in you. Like you’d come home a different person.”

“I am a different person, Jess. I don’t like who I am now. That’s part of the problem.”

She starts to cry again, and her tears oil the space between our cheeks. “Do you like who I’ve become?”

There’s a loaded question. From the moment I got off that bus at Pendleton, I wasn’t sure whom I’d face: Jessica, my high school sweetheart, the girl I fell in love with at prom, the wife who promised to send me letters every day, or the bitter woman whose words were like vicious right hooks to an open wound.

What had she become? As I stepped off the bus, I saw her waving at me. All around us, Marines were locked in bear hugs with wives and mothers and children. A sea of humanity celebrated our survival. It was a moment of total euphoria for most of us.

Jess approached me, arms wide, grinning wildly, sunglasses covering her eyes and her hair dyed black, like she’d gone Goth from guilt.

I shook her hand.

“Answer the question, Jeremiah. Please.” Jess sounds almost desperate.

“I think we’re still getting to know each other again.” That’s the best I can do. I leave unsaid what I’m really thinking:

I don’t know if I can love you, Jess, and not hate myself.

I add, “We don’t trust each other anymore.”

She’s quiet. I’m content to let the silence linger. My mother’s long asleep in her bedroom upstairs. The couch is comfortable, and I’m exhausted. After all that’s happened today, I’m just ready for some sleep. Still, we haven’t been this honest with each other in years. Part of me wants to just crawl in my shell and let it all pass. But Jess has always had a way of coaxing me to talk. I used to love sitting next to her, just shooting the breeze about anything that entered our heads. We had many long nights, many talks till dawn in high school. We fit each other perfectly, and even as we grew up together, I knew back then that I’d found the only woman I could ever really love. Now part of me feels trapped by that reality.

“Well, if we need to get to know each other, let’s do it right. Okay?”

“What do you mean?”

“We haven’t lived under the same roof since before your deployment.”

“That’s true.”

“When your leave is over, we’ll both go back to Parris Island.”

“Are you sure?” I ask.

“Yes. But you have to try, Jeremiah. Since you’ve come home, we’ve all been walking on eggshells.”

“I can’t tiptoe around you all the time, wondering what’s going to set you off next. We’ve got to learn to relax again.”

“I’m not sure how.”

“We’ll work on it.”

“Okay.”

She sits up and looks down into my eyes. “Okay? You don’t sound convinced.”

“I want to get better. But it’s been pretty bad, Jess, I don’t want you to kid yourself. I may be a lost cause.”

“You’re my cause.”

“We can’t bullshit each other. I’m going to be dealing with PTSD for a long time. That counselor from our group session? He was a Vietnam vet. He’s had PTSD longer than he was normal. That’ll probably be me.”

She looks uncertain now. Does she have the strength for this? I think we’re both silently asking that question without knowing the answer.

Am I strong enough for this?

I have to be. I can’t repeat my grandfather’s life. I can’t be that war hero whose life sinks deeper and deeper until death is the only way out.

“Ira Hayes,” I suddenly say. I sit up at the recollection, and the connection. My sudden movement startles Jess.

“Who’s that?”

“That old song. You know, the guy who always wore black?”

“Johnny Cash?”

“Yeah, that’s right, Johnny Cash.”

“What about him?”

“He sang about Ira Hayes.”

Call him drunken Ira Hayes

He won’t answer anymore

Not the whiskey drinking Indian

Or the Marine who went to war.

“God. If I’m not careful, that could be the story of my life.”

“Okay, I’m confused. I don’t know the song.”

“Jess, Ira Hayes was one of the Marines who raised the flag on Iwo Jima. He was a Pima Indian. And a national hero. He came home and got invited to the White House. He went on a tour all over the country.”

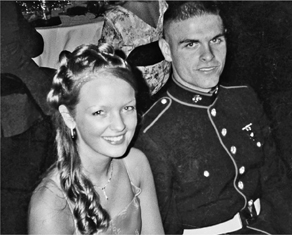

Jessica and me at her senior-year high school prom, 2003. I managed to get leave so I could drive home to Ohio and be her date. It was the longest I’ve ever had to travel for a night on the town!

AUTHOR COLLECTION

My sophomore year, we played Ridgedale High and beat them soundly on our way to a 9-1 season. Here I am trying to break a tackle after a ten-yard gain, wearing the great Tom Rathman’s jersey number. Like Rathman, I played fullback that year and gained about five hundred yards. My junior year, the coaches switched me to tailback and linebacker, positions I played for the rest of my high school career.

COURTESY OF THE RICHWOOD GAZETTE

My dad and I at Columbus International Airport the day I left for Parris Island and boot camp in 2001. I had just graduated from high school. Throughout school, my dad and I remained quite close. But after I joined the Corps, he all but disappeared from my life. AUTHOR COLLECTION

Jess and I on our wedding day, seen here leaving the church as our friends blew bubbles at us instead of tossing bird seed or rice. Not long after, the wedding party fractured as a disagreement arose at the reception, and we spent our first married night apart. AUTHOR COLLECTION

My platoon touched down in Iraq in the late summer of 2004. The C-130 Hercules carried us from Kuwait to the Anbar Province. We soon found ourselves in heavy combat. AUTHOR COLLECTION

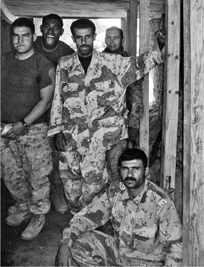

My 81mm mortar squad. Kneeling left to right: Lance Corporal White and our medic Doc Sunny. Standing left to right: Corporal Ryman, Corporal Levine, Lance Corporal Mullins, Corporal Smokes, and myself. This photo was taken on the outskirts of Fallujah in November, 2004, just as the battle kicked off. We fired thousands of 81mm rounds into the city with our tube as we supported the marine infantry battling house to house. The enemy tried to knock us out several times with counter-battery rocket fire. AUTHOR COLLECTION

A marine M-1 Abrams main battle tank thunders past my Humvee at the head of a long column of tanks and armored amphibious personnel carriers bound for their final staging point before we launched our offensive into Fallujah. The ground shook and the fillings in our teeth rattled as these massive vehicles passed us. It was a display of power I’ve never seen before or since. AUTHOR COLLECTION

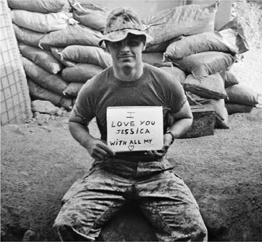

For weeks I had heard nothing from home. One day at Sac-town, I scribbled this note and an Iraqi soldier snapped a photo of it for me. I sent the picture in a letter to Jessica just before we left for Fallujah. She never replied.

AUTHOR COLLECTION

Mimoso and I prepare to saddle up for another Fallujah patrol. Our Humvees weren’t armored, but we used them every day inside the city. Here were are holding our full stock M16A4 rifles. Both of us had four power scopes instead of iron sights, which made long-range shooting much more effective, but at close quarters they were useless.

AUTHOR COLLECTION

February 1, 2005. Gardiola and Kraft pin my chevrons on my uniform as I am promoted to sergeant. It was one of the most meaningful moments for me in-country as these two men I respected and loved honored me in front of the rest of the platoon.

AUTHOR COLLECTION

Kraft and me on the roof of a damaged building at Sac-town, prior to the Battle of Fallujah. We spent hours up there in the heat, watching over an Iraqi police station. We never trusted the IPs, and we kept an eye on them as much as we did the enemy.

AUTHOR COLLECTION

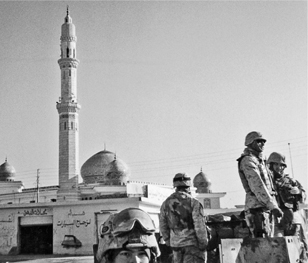

In Fallujah, the enemy used the local mosques as supply dumps and rallying points, hoping that we would stay out of them. Instead, our Iraqi Army allies searched the mosques whenever possible, and they almost always found massive weapons caches within their sacred walls. Doc Sunny and Eric Hillenberg are standing on the back of one of our Humvees.

AUTHOR COLLECTION

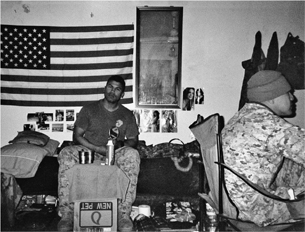

Our living quarters in Fallujah. We lived in a battered apartment complex. Kraft is sitting at right, watching an old Iraq television set he found somewhere. Meanwhile, Gardiola shaves with his canteen cup and a mirror.

AUTHOR COLLECTION

Left to right: Hillenberg, Doc Sunny, and Phillips stand with two “Swannis”—ex-Iraqi Special Forces soldiers who professed loyalty to the United States. We never trusted them, though we did patrol with them from time to time. Later, during the Battle of Fallujah, some of our Swannis were captured while fighting against us. It was that kind of war.

AUTHOR COLLECTION

Our three fallen brothers were not honored with a memorial service until just before we left Iraq in April, 2005. Our grieving was delayed four months by combat and circumstance. Once we did assemble to say our final goodbyes, it served only to reopen half-healed wounds. AUTHOR COLLECTION

On patrol in downtown Fallujah after the battle. Engineers stretched barbed wire along the sidewalks so civilians would not get into the streets and disrupt our vehicular patrols. We saw plenty of children on days like this—most wanted candy, but some saluted and waved. These houses were pretty typical of Fallujah: mini fortresses with many hiding places for enemy fighters waiting to ambush us.

AUTHOR COLLECTION

The effect of American firepower on downtown Fallujah. We patrolled through the city’s ruins for days in December, 2004, without seeing hardly another soul alive besides our men. It was an eerie 28 Days Later sort of feeling being in a city hollowed out by such destruction.

AUTHOR COLLECTION

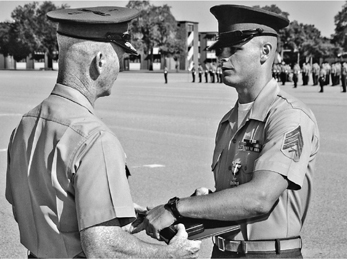

My Navy Cross ceremony at Parris Island evoked strong and bitter memories for me. We lost three men that day and each one deserved that award more than I did. AUTHOR COLLECTION

Left to right: Me, Jessica, her mom, Alma, and her stepdad, Von, at a meeting of the Ohio chapter of the Daughters of the American Revolution. This night was one of the first times I spoke about Iraq in public. I touched on patriotism and sacrifice, and spoke about the bravery I saw around me every day while we were in-country. AUTHOR COLLECTION

Easter Sunday, 2007. Jessica and me with our boy, Devon, who was two months old at the time. Jess, being a hairdresser, loves to change the color of her own hair. Here she is as a new mom with a new brunette look.

AUTHOR COLLECTION

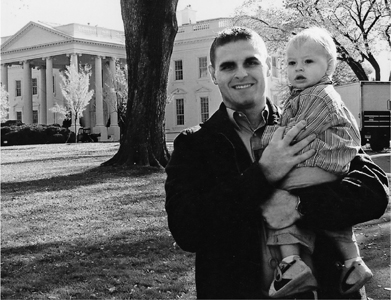

Devon and I on the north lawn of the White House in late 2007. Devon’s birth gave me renewed energy to face each day and continue my battle with PTSD. I live for him and Jessica now, and their love gives me the strength to overcome the memories of December 23, 2004.

AUTHOR COLLECTION

“So, he came home with what had to have been a real bad case of PTSD. He couldn’t take it.”

Comprehension flares in her eyes. Hesitant, “Did he kill himself?”

He died a drunk one morning

Alone in the land he fought to save

Two inches of water in a lonely ditch

Was a grave for Ira Hayes.

“No. He drank himself to death.” They found him facedown, smeared in his own blood and vomit. There was no dignity in the way he died. He’d suffered for ten years and rode a long slow ride downhill that ended in defilement and a senseless death. Truth be told, what he saw on Iwo Jima mortally wounded him in 1945. It just took ten years for the liquor to finish him off.

Maybe December 23rd is my flag raising. Am I dead and don’t even know it? I haven’t felt truly alive since Fallujah. And I’m in a long slow slide of my own.

“Oh.”

Yeah. Oh. Like oh shit. That ditch could be my fate, too.

I remember standing by the bus, shaking hands with Jessica, at a total loss of words for the moment. Suddenly, Kraft appeared and interrupted our awkward moment. He introduced me to his grandfather, the FBI agent, code-talker, and full-blooded Navajo. His grandfather stepped close to me and regarded me. He was elderly, his face lined and weaved with age.

“Thank you for protecting my grandson,” he said.

I didn’t know what to say. We looked out for each other.

“He comes home to us, thanks to you.”

“No, I’m here because of him.”

Grandfather Kraft smiled at that. Then he pulled out a small pouch. He opened it and began to streak my face with cornmeal. As he did, he sang a song in a language I’d never heard before. At first, this invasion of my personal space caught me off guard, and I thought it strange and rude. But as Grandfather Kraft continued, I felt a surprising surge of peace. I realized he was blessing me in Navajo. When he finished, I tried to thank him for this honor, but did a very poor job of it.

I wonder if Ira Hayes underwent a similar ceremony by his own people when he returned. Unfortunately for me, the blessing didn’t take. It just served as a signpost along the way of my own downward road.

I grow morbid now. “Then there was Chesty Puller’s son.”

Jessica looks questioningly at me, but doesn’t ask.

“Chesty was a legend in the Corps. Fought at Guadalcanal, all through World War II and Korea. He was the most decorated Marine.”

“What happened to him?”

“The Corps gave him five Navy Crosses.”

“Five?”

“Yeah.”

“Did he kill himself?”

“No, but his son became a Marine officer. Fought in Vietnam. Highly decorated. He stepped on a land mine that blew his legs off. I think parts of both arms, too.”

“Oh my God.”

I continue, “He came home. Went to law school. But he had huge ups and downs. Drank hard. Wife couldn’t take it, she left. He killed himself right after that. Sometime in the nineties, I think.”

“Jeremiah, why are you telling me this?” Jess looks stricken.

“It’s hard to be a ‘hero’ in the Corps, Jess. It means you went through a hell of a lot. You know?”

“Okay.”

“They had PTSD. Maybe we all have it to some degree.”

“What are you getting at?”

“History isn’t on our side. You need to know that. I’m just saying there aren’t a lot of success stories here.”

“Well, then we’ll have to be the first one.”