Why do some patients experience persistent symptoms after having received the recommended antibiotic treatment for Lyme disease? The primary hypotheses to explain this problem include:

• Persistent infection with B. burgdorferi,

• Residual damage to tissue from the original infection,

• Persistent immune activation and inflammation, and

• Borrelia-triggered neural network dysregulation including central sensitization and neurotransmitter changes.

These hypotheses are discussed in greater detail in this chapter.

While it has long been accepted in the medical community that B. burgdorferi can persist for months to years in a human who has not yet been treated with antibiotics, there has been significant debate over whether the infection could persist after initial antibiotic treatment of standard duration. A number of carefully conducted animal studies have now demonstrated convincingly that, even after antibiotic therapy, B. burgdorferi can persist in the animal host (Hodzic et al. 2008; Embers et al. 2012; Staubinger et al. 1997). The quantity of persistent B. burgdorferi is typically at lower levels than in a new infection. An animal study with mice has demonstrated that the Borrelia that persist are living, infectious, and capable of stimulating an ongoing immune response (Hodzic et al. 2014). However, these persistent Borrelia are not able to be cultured in the standard culture medium for Borrelia spirochetes. While many of these studies have been conducted in mice, studies in dogs and rhesus macaques have also shown persistent B. burgdorferi spirochetes (Straubinger et al. 1997; Embers et al. 2012).

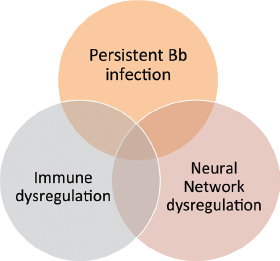

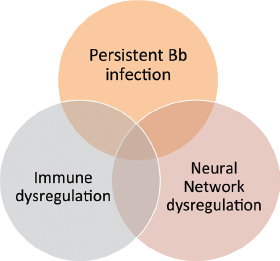

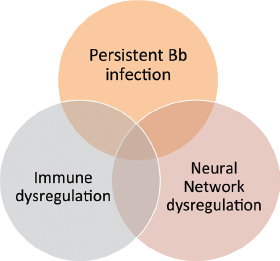

FIGURE 6.1

Treatment of post-treatment Lyme disease syndrome depends on the cause.

Culture is the gold standard for proving active infection with B. burgdorferi. Using the traditional culture medium (BSK), case reports in humans have been published confirming B. burgdorferi growth by culture after treatment—most of these are found in the early European literature on Lyme disease. There have been reports from Europe demonstrating culture of Borrelia from the skin of individuals with previously treated Lyme disease (Strle 1996). In the United States, as noted in chapter 5, a case report revealed positive growth of B. burgdorferi when the cerebrospinal fluid was cultured by the CDC from a patient who had received many months of prior antibiotic therapy for Lyme disease (Liegner et al. 1997). While rare, these cases prove that persistent infection in humans can occur.

Among those who agree that low levels of the bacteria can persist after initial treatment, there is additional debate over whether these low levels of spirochetes are causing clinically significant symptoms in patients and whether additional antibiotic treatment is helpful. For example, some studies in animals have shown that residual spirochetes do not cause the expected local inflammation when viewed microscopically, while more recent messenger RNA studies demonstrate that mice with residual spirochetes have altered tissue cytokine production, raising the hypotheses that these cytokines themselves, if produced in sufficient quantity, may be causing systemic symptoms (Hodzic et al. 2014).

How does the Borrelia spirochete persist despite the body’s immune surveillance or despite antibiotic treatment? There are several possible explanations.

• Analysis of both human and experimental animal tissues indicate that B. burgdorferi spirochetes are found intercalated in extracellular collagen-rich matrixes (components of connective tissue); this location may be a unique niche for immune evasion. The central nervous system which is a relatively immune privileged site may also facilitate immune evasion.

• In vitro laboratory-based evidence demonstrates that B. burgdorferi may be able to survive inside human cells, including endothelial cells (lining blood vessels), astrocytes (in the brain), fibroblasts (in connective tissue), and macrophages (in the immune system). Intracellular sequestration, however, has not yet been demonstrated in vivo in the animal or human.

• B. burgdorferi is known to modify its outer surface protein expression depending on temperature, pH, and other factors. For example, the outer surface protein expression of the initial invading spirochete is different from the outer surface protein expression of the spirochete that has been in the host for more than four weeks. By up-regulating or down-regulating the expression of surface proteins that are usually recognized by the immune system, B. burgdorferi spirochetes can escape detection and killing by the immune system.

• B. burgdorferi has the ability to produce proteins that bind to and inactivate a key component of the immune system, called complement. The production of complement inactivators has the net effect of markedly decreasing the destructive capacity of the antibodies against the spirochete.

• Other laboratory-based in vitro experiments indicate that Borrelia can revert to round forms, which appear less susceptible to standard antibiotic therapy. Whether this also occurs during human infection remains unclear.

• Recent evidence conducted in vitro in the laboratory setting demonstrates convincingly that a subgroup of Borrelia spirochetes (called “drug-tolerant persisters”) are not killed by the standard antibiotic therapy for Lyme disease. Research groups have identified different antibiotics or antibiotic combinations (Feng, Auwaerter, and Zhang 2015) or treatment regimens (Sharma et al. 2015) that are effective in the laboratory setting and now are being explored in animal studies. Until these novel agents or strategies identified by in vitro studies are tested in animal models to confirm improved efficacy over standard treatment, these antibiotic regimens are of uncertain clinical value.

By one or more of these mechanisms, B. burgdorferi may be able to persist inside the human body and it is possible that these persistent bacteria may be responsible for patients’ ongoing symptoms.

In 2012, a leading authority on Lyme disease research in animals provided his perspective on Lyme disease to members of the U.S. Congress (Barthold 2012). Excerpts from his introductory comments are quoted here.

Lyme disease, caused by a number of closely related members of the B. burgdorferi sensu lato family (B. burgdorferi sensu stricto in the United States) that are transmitted by closely-related members of the Ixodes persulcatus family (I. scapularis and I. pacificus in the United States) is endemic in many parts of the world, with particularly high prevalence in the United States and Europe. Prevalence of human disease continues to rise, as does the geographic distribution of endemic areas. These events are enhanced by perturbation of the environment by humans, as well as global climate change, which favor habitation of the environment by Ixodes spp. vector ticks and suitable reservoir hosts. Interest in Lyme disease is rising globally, as Lyme disease is increasing in southern Canada, where infected ticks and reservoir hosts are extending their range from the United States, as well as an increase in prevalence throughout Europe and Asia.

During the course of my Lyme disease research career, I have become saddened by the negative discourse and division that exists among various factions of the Lyme disease community, including the lay community, the medical community, and the scientific community (the so-called “Lyme Wars”). In particular, debate has intensified regarding efficacy and appropriate regimens for antibiotic treatment. Central to this debate is the Infectious Disease Society of America (IDSA) position that this is a simple bacterial infection that is amenable to simple antibiotic treatment, while also recognizing that something is happening in patients after treatment, known as Post Lyme Disease Syndrome (PLDS).

Lyme disease is exceedingly complex in humans, and this poses major challenges to accurate diagnosis and measuring outcome of treatment. It has been known for years that the acute signs of Lyme disease (erythema migrans, cardiac conduction abnormalities, arthritis, etc.) spontaneously regress without benefit of antibiotics, but their resolution is accelerated by treatment. There is overwhelming evidence in a variety of animal species as well as humans that B. burgdorferi persists without treatment, but the crucial question is does it survive following treatment, and if so, do surviving spirochetes cause “chronic” Lyme disease or PLDS? These questions cannot be answered by speculative and expensive human clinical trials motivated by firmly held dogmatism.

Something strange is happening with Lyme disease. B. burgdorferi persistently infects a myriad of fully immunocompetent hosts as the rule, not the norm of its basic biology. When such a situation occurs, antibiotics may fail, since it is generally accepted that antibiotics eliminate the majority of bacteria, and rely upon the host to “mop up” the rest. If the bacteria are able to evade host “mopping,” then the logic of the scenario falters. It is not surprising, therefore, that experimental studies, using a broad spectrum of animal species (mice, dogs, monkeys) and a variety of antibiotics (doxycycline, amoxicillin, ceftriaxone, tigecycline) have all shown a failure to completely cure the animals of B. burgdorferi infection. What is surprising is that the surviving spirochetes can no longer be cultivated from tissues (culture is considered by some to be the gold standard for detecting viable B. burgdorferi), but their presence can be readily detected with a number of methods, including B. burgdorferi-specific DNA amplification (polymerase chain reaction [PCR]), xenodiagnosis (feeding ticks upon the host and testing the ticks by PCR), detection of B. burgdorferi-specific RNA (indicating live spirochetes), and demonstration of intact spirochetes in tissues and xenodiagnostic ticks by labeling them with antibody against B. burgdorferi-specific targets. These surviving spirochetes are not simply “DNA debris” as some contend, but are rather persisting, but non-cultivable spirochetes. It remains to be determined if their persistence following treatment is medically significant. For example, humans are known to be persistently infected with a number of opportunistic pathogens, including viruses, bacteria, and fungi, which are held in abeyance by the immune response, without clinical symptoms. Their significance varies with individual human patients and their ability to keep them in check. Lyme disease is likely to be similar.

The key points from this statement are as follows:

• Lyme disease is not a simple disease because the agent of infection, B. burgdorferi, is highly complex.

• The basic biology of B. burgdorferi is that it can persist and survive immune attack, which can make it hard to eradicate.

• Antibiotics are expected to wipe out the majority of infection, but not all of it; a healthy immune system is meant to conduct the final sweep to eradicate the infection from the body. Because B. burgdorferi has evolved mechanisms by which it evades the immune system, it is not surprising that some spirochetes will persist.

• A preponderance of evidence now exists demonstrating persistent infection in the animal model despite antibiotic treatment, but these spirochetes can no longer be cultivated from the host’s tissue. This suggests that the persistent Borrelia spirochetes are not as healthy as the initial infecting spirochete or that they are simply not actively replicating.

• The extent to which the residual noncultivable spirochetes cause clinically significant disease remains to be determined.

In general, Lyme disease is not associated with prominent tissue damage that persists after treatment. This is good news of course, but it is not necessarily true for all manifestations of Lyme disease. Patients with neuroborreliosis-induced vasculitis may experience long-term residual neurologic effects of a stroke. Patients with facial nerve palsy may have long-standing residual facial weakness.

The immune response and inflammation may persist even after antibiotic treatment of the infection. This observation has led to the hypothesis that either a small amount of persistent infection or spirochetal residua continue to trigger the ongoing immune response or that this is a postinfectious process, triggered but not sustained by active infection.

This hypothesis is supported by several lines of evidence. For example, patients with Lyme arthritis who carry the HLA-DR4 gene are more vulnerable to developing a chronic immune-mediated antibiotic-resistant arthritis (Steere, Dwyer, and Winchester 1990). In addition, three autoantibodies have been identified that are reasonably specific for antibiotic-refractory Lyme arthritis (antibodies against endothelial cell growth factor [ECGF], apolipoprotein B-100, and matrix metalloproteinase 10); supporting a role in pathogenesis, the levels of anti-ECGF auto-antibodies in one study were shown to correlate with obliterative microvascular lesions in synovial tissue (Londono et al. 2014).

Among patients with post-treatment Lyme disease syndrome (PTLDS), there is indirect evidence implicating “molecular mimicry” in pathogenesis, meaning that B. burgdorferi has outer surface proteins that mimic human cells so that the immune system accidentally attacks itself in addition to the invading bacteria (Jacek et al. 2013; Chandra et al. 2010). There is also evidence to suggest that remnants of the Borrelia spirochete in tissues may result in a persistent activation of the immune system, causing the production of inflammatory cytokines, such as interleukin-6 (IL-6) and tumor necrosis factor.

Evidence of post-treatment immune activation has emerged from several research groups:

• Several studies (Jacek et al. 2013; Chandra et al. 2010) document ongoing immune reactivity among patients with PTLDS.

° Using samples from the Columbia University clinical trial, these researchers reported persistently elevated activity levels of the cytokine interferon-alpha in the serum of patients who were treated for Lyme disease but who continued to experience memory problems. This heightened immune response was proposed to have occurred due to prolonged exposure to Borrelia prior to treatment. The importance of this study was that it provided evidence in support of the hypothesis that patients with PTLDS have ongoing immune activation that may be contributing to some disabling PTLDS symptoms such as fatigue and malaise.

° Using samples from the New England Medical Center clinical trial (Klempner et al. 2001) and the Columbia clinical trial (Fallon et al. 2008), these researchers demonstrated that patients with PTLDS have elevated levels of antineuronal antibodies—comparable in magnitude to what was seen in a comparison sample of those with an autoimmune disease, systemic lupus erythematosus. Of importance, individuals with recovered Lyme disease did not show elevated levels of these antineuronal antibody biomarkers.

• Using samples from a Slovenian clinical trial (Strle et al. 2014), serum from patients with early Lyme disease versus PTLDS was probed for the levels of twenty-three cytokines and chemokines before and after antibiotic treatment.

° Of the forty-one patients with detectable IL-23 levels at initial presentation, twenty-five (61 percent) developed post-treatment symptoms, and all seven with high IL-23 levels had PTLDS symptoms.

° Among those patients with post-treatment symptoms, antibody responses to the ECGF autoantigen were more common than in patients without post-treatment symptoms and ECGF antibody responses were correlated directly with IL-23 levels.

° This study demonstrated that a particular immune response (high TH1) at initial presentation was correlated with more effective immune-mediated spirochetal killing, whereas another immune response at initial presentation (high TH17), often accompanied by autoantibodies, correlated with post-treatment Lyme symptoms. This study confirms that variable immune responses at the very start of infection may provide clues as to who will be vulnerable to developing PTLDS. Noteworthy is that the main function of IL-23 is to drive TH17 cells, which are important in host defense against extracellular pathogens. It is also noteworthy that aberrant IL-23/TH17 responses have been implicated in several autoimmune conditions, including rheumatoid arthritis, inflammatory bowel disease, lupus, and type 1 diabetes.

• Using samples from the Johns Hopkins biorepository of patients followed prospectively from the initial Lyme rash to the six-month follow-up after treatment, a study (Soloski et al. 2014) demonstrated that in some patient samples over six months there was an ongoing production of the inflammatory cytokine IL-6. The authors hypothesized that the persistent inflammatory process in a subset of individuals after treatment may be due to “residual antigen or infection in some treated Lyme disease patients,” as has been observed in the animal model studies, but they note that to test this hypothesis in humans, a larger sample size and additional exploration are required.

It is difficult to determine in a particular individual whether ongoing symptoms and immune activation are due to a small amount of persistent infection or to a postinfectious process. It is clear, however, that the brain is a central mediator of most bodily processes. Brain networks and the immune response may be triggered by active infection or remain aberrantly activated by past infection.

Why include the brain in this chapter? The brain can be viewed as the computer-processing center of the body. Neural activation networks can be viewed as the software that shapes how information is processed in the brain. Changes in brain hardware or software will have an impact on the patient’s clinical presentation and the ability to resolve chronic illness. While it is easy to comprehend that problems with memory or mood are related to brain mechanisms, it is not as often recognized that inflammation and immune processes in the body are also shaped by input from the brain. This concept is of great importance for individuals with chronic illness because the problem may no longer be due to persistent infection but rather to the impact of the initial infection on the brain’s activation patterns.

Central Sensitization in the Brain and Pain

Central sensitization is a process that has been proposed to occur in chronic pain disorders, including fibromyalgia, chronic fatigue syndrome, migraine, and possibly PTLDS. These disorders share the symptoms of persistent pain and fatigue as well as sensory hyperarousal. Patients with central sensitization feel abnormally increased pain in response to a mildly uncomfortable stimulus, such as having blood drawn, and may even feel pain from a stimulus that is not painful to others at all, such as the sensation of clothing on the skin. It has been shown that patients with fibromyalgia have abnormally hyperactive brain pathways that control pain (Clauw 2014). Patients with central sensitization may also be intensely bothered by bright lights or loud sounds. It has been hypothesized that patients with central sensitization have a genetic predisposition to this condition that can be triggered by trauma or an infection. In the case of fibromyalgia, first-degree relatives of patients with this condition have an eightfold greater risk of developing it (Arnold et al. 2004). Central sensitivity may also result from an imbalance of neurotransmitters involved in the pain response including serotonin, norepinephrine, GABA, glutamate, and dopamine. Once central sensitization occurs, it may persist due to structural and functional changes in the brain. It is possible that chronic symptoms triggered by Lyme disease are caused, at least in part, by central sensitization, in which case treatments should focus on decreasing the hyperactivation of these pain pathways in the brain (Batheja et al. 2013).

It is reasonable to assume that some patients with chronic symptoms after initial treatment for Lyme disease suffer from persistent infection, whereas others suffer from a postinfectious ongoing immune process (autoimmune disease, infection-triggered immune activation) and others suffer from abnormally sensitized brain pathways (e.g., central sensitization), though more research needs to be done on each of these potential causes. Decisions about treatment have largely focused on antibiotic selection when acute infection is present, but emerging evidence suggests that patients with persistent symptoms after treatment may also benefit from immune modulatory strategies (Steere and Angelis 2006; Rupprecht et al. 2008) or from neurotransmitter modulatory strategies (Weissenbacher et al. 2005).

The Immune-Body-Brain Link

The immune response has often been viewed inaccurately as an independent process that works by itself to defend the body against infections or other foreign substances. We know, for example, that the brain has an enormous influence on all bodily systems, such as the gastrointestinal tract and the cardiovascular and neuroendocrine systems. There is now considerable evidence that the immune system and the nervous system are functionally and anatomically connected.

This concept was demonstrated quite clearly by an experiment in the early 1990s in which the inflammatory cytokine (IL-1B) was injected into the abdomen of rodents (Watkins et al. 1995). Under normal circumstances, such an injection would cause a fever in the rodent. When one of the cranial nerves that innervates peripheral organs was cut (the vagus nerve), the fever did not occur. In other words, an intact nerve fiber connecting the brain to the abdomen was required to allow information from the abdomen about inflammation to be conveyed to the brain so that the fever response could occur. In a later rodent study, it was demonstrated that electrical stimulation of the vagus nerve decreases peripheral inflammation (Borovikova et al. 2000). Further evidence demonstrating the importance of the vagus nerve in controlling inflammation was provided by a study of humans with chronic refractory arthritis who received electrical stimulation of the vagus nerve (using a subcutaneous surgically implanted device); the results demonstrated an inhibition in the production of tumor necrosis factor (an inflammatory cytokine) and an improvement in clinical measures of pain and functioning (Koopman et al. 2016).

These studies therefore demonstrate that there are key neural pathways by which the brain modulates the inflammatory response. The immune system and the brain are intimately connected. This insight is critical as it suggests that abnormalities in brain function could also lead to abnormalities in immune response. This is relevant to Lyme disease in that infection with B. burgdorferi in some patients leads to altered brain metabolism and blood flow, as demonstrated by our group at Columbia (Fallon et al. 2009). Compared to well-matched controls, individuals with persistent cognitive impairment after Lyme disease (all of whom had received considerable prior antibiotic therapy) had multiple areas of decreased metabolism and blood flow, primarily in the temporal-parietal regions. Whether these regional brain alterations impact the immune response directly is not clear, but abnormalities in these brain regions are known to be associated with many of the cardinal symptoms experienced by patients with Lyme encephalopathy, including cognitive impairment and fatigue.

It remains an intriguing question whether normalization of brain function and metabolism would have a beneficial impact upon immune system function. Based on the vagal nerve stimulation studies that have demonstrated a reduction in the peripheral blood levels of several inflammatory cytokines (e.g., TNF-α, IL-1β, and IL-6), it is equally important to ask whether vagal nerve stimulation would reduce chronic Lyme arthritis or the diffuse musculoskeletal pain and fatigue associated with PTLDS.

Recent studies in immunology have suggested a link between the long-term immune activation associated with many chronic illnesses and clinical depression. In response to infection, the innate immune system produces small signaling molecules called cytokines, some of which cause inflammation (examples of pro-inflammatory cytokines are TNF-α, IL-1α, IL-1β, and IL-6). These cytokines are thought to act on the brain to cause “sickness behavior” that includes loss of appetite, loss of interest in daily activities, sleeping problems, and irritability. When the infection lasts for months or years, so does the inflammation; the ongoing sickness behavior in certain vulnerable individuals may progress to clinical depression. Researchers now have good evidence to conclude that chronic inflammation increases the risk of major depressive episodes (Dantzer 2009; Hoyo-Becerra, Schlaak, and Hermann 2014).

• Studies of patients receiving cytokine therapy to treat chronic diseases such as for hepatitis C showed that these patients were at higher risk for developing major depressive episodes (Miller and Timmie 2009). Initially, these patients developed flu-like symptoms, fatigue, loss of appetite, chronic pain, and sleep disorders that were then followed by cognitive problems, depressed mood, anxiety, and irritability. Cytokines have also been shown to induce depression in animal studies.

• Additional research suggests that biomarkers of inflammation may help to guide treatment choice for depression. One study reported that depressed patients with signs of systemic inflammation such as elevations of C-reactive protein (CRP) were more likely to respond to a noradrenergic agent such as nortriptyline, whereas those with low CRP levels responded more favorably to serotonin reuptake inhibitors (Uher et al. 2014).

• A meta-analysis of twenty studies examined the impact of anticytokine drugs on depressive symptoms in chronic inflammatory diseases, including seven placebo-controlled randomized trials. The authors concluded that these immune modulators (most commonly agents that reduced tumor necrosis factor) resulted in significant improvement in depressive symptoms (Kappelmann et al. 2016). Of particular note is that improvement in depression was unrelated to improvement in physical symptoms. Modulation of inflammatory cytokines therefore may emerge as a novel approach to treatment of patients with depression, particularly when there is evidence of inflammation.

In addition to chronic illness, ageing and obesity are also thought to be associated with increased activity of the immune system and chronic inflammation. The interrelation of chronic illness, immune activation, and mood is an area of ongoing research.

The gut microbiome plays an important and as yet relatively unexplored role in the human. The likelihood that bacteria in the gut play a critical role in human health should not be surprising because the number of bacterial cells in the human body (i.e., predominantly in the gut) is ten times greater than the number of human cells; more dramatically, some state that the human body is simply a bag of microbes. The bacteria in the gut, while generally stable throughout life, can be altered by environmental factors such as infection, nutrition, antibiotics, and probiotic use.

One important area of future investigation is the impact of long-term antibiotic use on the rest of the body. Could the consequent imbalance in the intestinal flora be contributing to chronic symptoms such as fatigue, brain fog, and/or pain? Could immune-mediated diseases be triggered by these changes in the gut microbiome? These questions have not yet been studied in a systematic manner in regard to Lyme disease, though scientific interest is mounting.

Recent studies suggest that alterations in the gut microbiome may be key players in the pathophysiology of medical conditions as diverse as obesity and inflammatory bowel disease (Thomas et al. 2017). Rodent models have shown that bacteria in the gastrointestinal tract influence the development of autoimmunity. We also know that nutrition has an impact on the gut microbiome, which in turn can impact the innate and adaptive immune systems. This interaction is not always straightforward. For example, spore-forming bacteria have been found in animal models to support the development of autoimmune arthritis and encephalomyelitis (Block et al. 2016; Lee et al. 2011), but these same bacteria have been found to be protective against the development of type 1 diabetes (King and Sarvetnick 2011). This is a medical field at its earliest stages. The impact this research will have for patients experiencing persistent symptoms after Lyme disease remains to be determined.

Does the gut microbiome have anything to do with cognition or mood?

• Studies conducted in animals that have been depleted of their intestinal microbes demonstrate that the brain’s neurotransmitter system (e.g., monoamines) then develops abnormally, resulting in memory and behavioral problems (Crumeyrolle-Arias et al. 2014).

• Germ-free mice have reduced fear responses. Remarkably, this can be reversed. If the intestinal bacteria are returned to the mice early in development, a normal fear response occurs once again (Cryan and Dinan 2012).

• The probiotic Lactobacillus rhamnosus causes major changes in the expression of the inhibitory neurotransmitter GABA (gamma-aminobutyric acid) receptors in the brain, resulting in an enhanced antianxiety response in animals (Bravo et al. 2011). Interestingly, this effect requires an intact vagus nerve. When the vagal connection between the gut and the brain is cut, the beneficial reduction of anxiety by the impact of Lactobacillus from the gut on the GABA receptors in the brain does not occur. This is one more animal study demonstrating that mood is modulated by the bacteria in the gut and that there is a direct interaction between the brain and the gut.

• A recent randomized double-blind placebo-controlled clinical trial of the probiotic Bifidobacterium longum among patients with irritable bowel syndrome revealed a modest reduction in depression, an improved quality of life, and reduced neural reactivity to negative emotional stimuli in limbic brain regions among the probiotic-treated patients compared to controls (Pinto-Sanchez et al. 2017).

These hypotheses about the role of the microbiome in chronic illness and its impact on brain activity are only just beginning to be tested. We present them here as examples of new directions in our efforts to understand the complexity of the human illness response and possible future relevance to Lyme disease.

Everybody has experienced somatization or anxiety at some point. Somatization is a process by which distressing physical symptoms arise due to psychological mechanisms. In its mild forms, individuals may experience “butterflies in the stomach” or a need to urinate when under stress. Somatization can become enhanced by excessive attention to one’s bodily symptoms, by catastrophic beliefs about the potential significance of these symptoms, and by underlying mood or anxiety disorders.

• An example of attention and the power of suggestion leading to somatization would be if a patient is told that he or she may experience a flare of symptoms within the first few days of initiation of antibiotics, called a “Herxheimer reaction.” This exacerbation of symptoms shortly after starting antibiotic therapy is thought to be due to a flare of the immune system in response to the killing of spirochetes. While this can indeed occur as an early consequence of antibiotic treatment, the anxious, hypervigilant patient may then hyperfocus so intensely on minor bodily symptoms that the sensation itself is experienced more intensely and the individual becomes increasingly distressed. At times, such hyperfocused attention on bodily symptoms and the resulting anxiety can lead to the shortness of breath, numbness and tingling, increased pain, or a systemic stress-related rash.

• Although Herxheimer reactions can be a valuable “tip” to the treating doctor that antibiotics are having an effect, the physician may be misled if the patient was previously warned to expect a Herxheimer reaction. We are not recommending that a patient not be warned because having such a reaction can be quite disconcerting to the patient. However, the clinician should be aware that how he or she discusses this potential reaction with the patient could influence the outcome. In other words, sometimes an exacerbation of symptoms is a Herxheimer reaction, while at other times it might be a sign of anxiety or somatization.

• Educating the patient about Lyme disease can be helpful in reducing anxiety. For example, here are several anxiety-reducing statements:

° The goal of antibiotic treatment is not to eradicate all B. burgdorferi bacteria in the body, but rather to give the immune system a head start by killing enough bacteria so that the immune system can then take over, mopping up any remaining spirochetes. Healthy immune systems are typically able to do this.

° In culture and in animal studies, Borrelia grow very slowly over the course of weeks and months. Patients who report feeling a resurgence of symptoms within a couple of weeks after ending an antibiotic course could be informed of Borrelia’s slow growth; because the growth is so slow and the remaining organisms (if present) would be quite few in number, it is unlikely that these symptoms are arising because of spirochetal activity. Rather, it may be that the antibiotics—in addition to their antimicrobial benefit—were also providing an anti-inflammatory effect. Not having this anti-inflammatory effect could lead to a rapid return of symptoms.

° Some symptoms may be due to the secondary effects of other primary symptoms of Lyme disease. For example, pain due to Lyme disease may lead to poor sleep. Poor sleep can lead to impaired attention, brain fog, irritability, and increased pain. In other words, the “foggy” brain and ongoing pain may be due to poor sleep rather than direct effects of active infection.

° Some physical symptoms may be due to anxiety itself. Patients are often relieved to learn that anxiety can manifest in quite diverse physical ways, such as chest pain, trouble breathing, numbness and tingling, and heart palpitations. These physical symptoms can arise out of the blue, when one is calm, or even while one is asleep. In fact, these symptoms among patients with primary anxiety (not Lyme disease but Panic Disorder) may be so severe as to lead symptomatic individuals to emergency rooms or to a host of medical specialists, such as cardiologists and neurologists. Fortunately, treatment of the anxiety leads to a remission in the physical symptoms.