Resolve not to be poor: whatever you have, spend less. Poverty is a great enemy to human happiness; it certainly destroys liberty, and it makes some virtues impracticable, and others extremely difficult.

—Samuel Johnson

Now comes the hard part—how to preserve your wealth in the coming crisis.

Caveat: If the Obama proposals to significantly increase taxes on dividends and capital gains go through, this would be a huge negative for the US and possibly all global markets.

I will start with a disclaimer. Cataclysmic events don’t happen often, and when they do most pundits are taken by surprise. I read lots of authors and get lots of newsletters on investing. I am continuously amazed at the certainty these authors have regarding the investing future, particularly since they don’t usually agree with one another and, looking back, their mistakes are plentiful. The “illusion of knowledge,” as historian Daniel Boorstin put it, is very dangerous. But it sells books.

Wall Street, on average, tends to be cautiously optimistic. Sell-side Wall Street economists, strategists, and analysts are not paid to be pessimists. If they are too optimistic and wrong, they are forgiven. If they are too pessimistic and wrong, they are fired.

OK. Here’s my version of a disclaimer. Investment forecasting can be hazardous to your fiscal health. But investors don’t have a choice. They must do it anyway. Buy and hold equity strategies for the US have worked over the very long run. But who lives that long? Periods of dramatic underperformance—like 1929–1933 and 1966–1981—are not rare. And other less fortunate countries—like Japan and Germany, which suffered crushing defeats in wars—offer more somber histories. And peacetime Japan from 1991 until the present has not been good for buy and hold equity investors either.

So let’s begin with a forecast of asset classes that may outperform in the coming years.

What follows is not the typical laundry list of stocks or alternative investments to buy. And it is certainly not a short-term trading guide. Rather, it is an assessment of what asset classes might preserve wealth and what long-term trends might offer opportunities in what looks like a difficult investing environment in the years to come. Some of these assets may be relatively cheap right now. Some may be expensive. I don’t want to get into a discussion about price-to-earnings ratios (PEs) or current valuations or whether near term the global markets are ready to go up or down. This book is not about whether the United States will have a double-dip recession in 2013(the odds do favor this) or whether China will have a hard or soft landing.

2008 showed that when the markets panic—and no doubt, some panics do lie ahead—the markets throw even the best stocks out the window. Timing is for the reader to decide. Sophisticated investors may want to consider hedging activities such as selling out-of-the-money calls on stocks they own. What follows below is a discussion of longer-term trends and investor strategies in an environment of sovereign debt defaults (broadly defined) and predator governments desperately seeking funds any way they can get them.

Let’s start out with the first asset every portfolio should have some of—CASH. There are so many uncertainties. Some cash, it seems to me, is advisable. It’s just common sense. Investment advisers don’t usually recommend cash, especially in a zero-interest-rate environment. Why pay someone to invest your money in something with a zero return?

But what kind of cash?

For this discussion, we define Cash 1 as cash or near cash investments in dollars, euros, or pounds. In many ways, Cash 1 seems like the logical asset choice for investors whose home currencies are the dollar, the euro, or the British pound. A major financial crisis will arrive when the core advanced countries like the United States have trouble funding their debt. Markets as they did in 2008 may crash around the world. Then with all your cash you can start buying and pick up bargains. A simple strategy: stay in cash until that day arrives. (Although nobody’s going to ring a bell and tell you when that day is.)

The problem with that is that cash—whether it’s dollars, euros, or British pounds—in nominal terms earns near zero. And in the United States and other countries that trivial return is taxed! Check out your favorite money market fund. In real terms—that is subtracting out current CPI inflation and the tax insult—cash earns a negative return. Cash, to some extent, is a bet on deflation.

Government statistics ex-Japan in the major countries show current CPI inflation running between 2 and 3 percent on an annual basis (3 to 4 percent in the case of the United Kingdom). Making for an even darker picture, central bankers around the world are openly wishing for higher inflation. Nevertheless, if Japan is our near-term future, then deflation is a possibility.

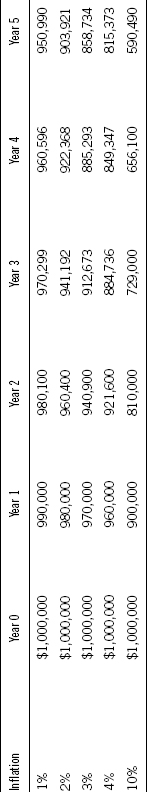

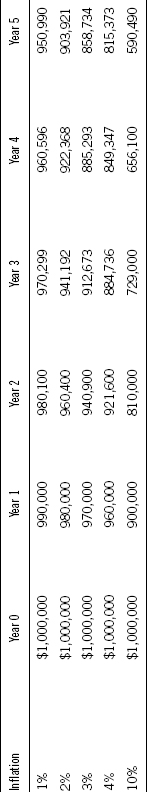

If inflation persists, the longer you hold Cash 1, the more you lose. Just to take the opposite side of my own recommendation, Table 7.1 gives some idea of how quickly the losses build up in terms of real purchasing power. $1,000,000 in year zero drops to $940,900 in three years assuming 3.0 percent inflation and 0 percent interest rates, but ignoring taxes. Holding cash with 0 percent interest rates and 10 percent inflation (remember the 5 percent to 9 percent that Shadow Government Statistics calculates for the US CPI under older methodologies) would be downright catastrophic, as Table 7.1 shows. If the crisis is five years out, people waiting in Cash 1 will be even poorer when the big day comes. When a central banker says he has an inflation target of 2 percent or more, with today’s near-zero interest rates he’s telling the holders of his currency—consider it a product that he is in charge of—that he wants them to lose money by holding his product.

Table 7.1 Cash Loss of Purchasing Power $1 Million

Of course, what the table doesn’t show is if we had actual deflation. Then, in terms of real purchasing power, holders of cash would experience an increase. In a deflationary or near deflationary environment, holding cash in US dollars may be the best conservative strategy.

Investors in cash are fighting with bankrupt predator states. The various monetary interventions (i.e., QE1, QE2, and QE3; LTRO; Operation Twist II), are funding these states. They have reduced the cost of paying interest on government debt even as the total amount of government debt continues to rise. They are manipulating investors to take risks they might not otherwise take. The monetary interventions are distorting the cost of capital, increasing the role of government in the economy at the expense of the private sector, and possibly setting the stage for big inflations in the future and impoverishing the investor class.

But there’s one more problem. If the crisis does come, your dollars and euros and pounds may depreciate against gold and against other currencies whose countries don’t have a huge debt crisis. So if you hold Cash 1, make sure you don’t include those fiscally strong countries in your future travel plans. You won’t be able to afford them.

OK, I’ve run through all the negatives. But it’s still common sense. If the world is as unsafe and unsure as I think it is and the crisis doesn’t drag on for ten years, you might be glad you had your cash.

Note we’ve left the Japanese yen out of what we call Cash 1. The Japanese have huge foreign exchange reserves and are running zero to slightly negative CPI inflation. Ignoring the practical difficulties for non-Japanese, holding cash in yen, at the moment anyway, carries less risk than the Cash1 currencies. In fact, for Japanese investors, holding cash near term has been a smart decision. Again, as has been argued, most observers, particularly Western observers, are clueless about Japan. Japan is supposed to be collapsing as we speak from a debt overload. But it isn’t.

But there are other cash alternatives. Who said you needed to keep all your cash in dollars, euros, or pounds? There are alternatives, if only to diversify partly out of the major currencies.

Ideally, we’re looking for global financial centers for whose major business—finance—depends on the soundness of their currencies. If a country’s major business is money, then it is more likely to take care of its money. You don’t take the attitude of the Fed, the Bank of England, the ECB, and the Bank of Japan that there are macroeconomic “greater goods” that take precedence over the soundness of your currency.

What we want from Cash 2 countries is a safe place to warehouse money where the Cash 2 currencies appreciate against the deteriorating global reserve currencies, including the US dollar. If we can find assets in these financial centers that offer reasonable yields, so much the better.

My ideal Cash 2 financial center has a long list of positive attributes:

The list of countries that might qualify for Cash 2 is not a long one. Singapore, Hong Kong, and Switzerland are this book’s recommendations. Stashing some of your money there or going long their currencies while waiting for the financial Apocalypse may be a good idea. There is one major risk. These global financial center economies are highly integrated into the global economy. If the global economy tanks in a major way, they will be hurt. But so will the rest of the world.

Australia and Canada are fiscally responsible countries with a lot of positives. But money (i.e., finance) isn’t their main business. They are not finance-driven countries. Their dependence on commodities, energy, and China are near-term negatives. We’ll put them in the Cash 3 category. Financially solvent countries like Chile may not welcome significant inflows of capital. Panama, definitely an emerging financial center as onerous US laws drive off Latin wealth management business, uses the US dollar and doesn’t have a significant stock market. And, although things have improved significantly in Panama, it has a very checkered past as far as political stability goes. Dubai is an emerging financial center but it is still recovering from its huge real estate hangover. And Dubai, located in the Persian Gulf with Iran only a little more than a nine iron away across the Persian Gulf, is not in the happiest neighborhood.

There are a number of ways for individual investors to get their money into these Cash 2 countries. Of course, they can always fly there and enjoy life as they open their accounts. But the global economy provides lots of options. Even Americans get a break. Local banks may not want to deal with them but a number of American brokerage firms are now offering the ability to trade foreign stocks on line and will allow clients to carry cash balances in foreign currencies. ETFs exist to go long the majority of currencies (and, thus, short the US dollar). American brokerage firms will include all foreign transactions placed through them in their annual 1099 IRS form for Americans. Presumably, similar services are available in other non-US countries.

For those readers unfamiliar with the following three Cash 2 countries, the following is a brief description:

For some people, Singapore is a sticky, tropical, authoritarian state that whips its citizens when they are bad, gags the press, and bans chewing gum.

Caricature to be sure. But I would say—with tongue only partly in cheek—that even this caricature should pique the serious investor’s attention. After all, who wants to deal with a banker who chews gum? Singapore is not Venice Beach (California) and hopefully never will be. And yes, Steve Jobs probably wouldn’t have liked to live there. Although Edward Saverin, a Facebook cofounder who nowadays is more of a rentier than creator like Jobs or Facebook CEO Mark Zuckerberg, has taken Singaporean citizenship. Perhaps Singapore’s vaunted Changi Airport should have a sign—Give me your rich, your persecuted capital, yearning to be free.

Singapore is well on its way to becoming the Switzerland of Asia. It welcomes foreign capital and the wealthy people of the world. It is becoming a major money management center for the new wealth of Asia. The visitor is impressed by Singapore’s ultramodern skyline, which now includes the iconic Marina Bay Sands towers. Marina Bay Sands is one of two casino/entertainment/integrated resorts that now attract visitors to the city-state. Only Dubai and Abu Dhabi can rival Singapore for architectural daring. The ultramodern skyline by the way coexists with a number of well-preserved colonial era buildings. All of this in a garden-like tropical setting as Singapore promotes itself as “The Garden City.” Which indeed it is.

This is a highly literate, wired country. English is the lingua franca and the language of finance, business, education, government and law. But thanks to the government’s bilingual educational policies and the country’s multiethnic makeup (as of 2011 74.1 percent Chinese, 9.2 percent Indian, 13.4 percent Malay), Mandarin, Tamil, and Malay are also official languages and are widely spoken as well.

One reason, by the way, that the print media is controlled is to avoid interracial strife. The policy has worked, as the race riots of the 1960s have been replaced by a general respect and camaraderie among Singapore’s various groups. (Recently, when a PRC Chinese couple objected to a Singaporean Indian neighbor’s kitchen’s curry smells, it seemed like the entire nation rose up to support the Indian neighbor’s right to cook with curry and thus perfume the neighborhood with its olfactory charms.) The Reverend Al Sharpton, the notorious and outspoken African American leader in the United States, would have a short career in Singapore. Singapore is a meritocracy, and racial quotas and race baiting are taboo. The contrast with Malaysia, with its bumiputra policy of racial quotas favoring Malays, could not be more acute. The economic numbers contrasting Singapore and Malaysia favor Singapore more every year.

Singapore is a parliamentary republic with a Westminster system of unicameral parliamentary government. Singapore has been run since independence in 1966 by one party, the People’s Action Party (PAP). The PAP takes a very technocratic, nonpopulist approach to governing, and frankly, it has done a damn good job. Elections are held regularly and, yes, the electoral structure and the print media are moderately “tilted” in the PAP’s favor. But there is no voter fraud, and if the electorate really wanted to kick the PAP out, they could. In fact, in last year’s general election, the PAP had a tough fight. Accusations that Singapore is a dictatorship are gross exaggerations. The winds of populism (unfortunately, in our opinion) have infected parts of Singapore’s younger population that doesn’t remember the struggles of earlier years. But the next election is probably four years off. James Madison would probably like Singapore.

Singapore as a former British colony has inherited a British-based legal system and the English language. For a brief period 1963–1965, Singapore was part of the Federation of Malaysia. But due to Chinese–Malay rivalries, it was kicked out. Lee Kwan Yew, Singapore’s leader and the man who could be regarded as the founder of modern Singapore, openly cried on television when this happened. He saw a bleak future for his little island, devoid of resources and industry. But MM (Minister Mentor), as he has been more recently called, was wrong. Singapore has boomed. People and brains are more important than resources. MM would cry again if he were told today that Singapore suddenly was back in Malaysia.

Finally, there is the subject of small. Singapore is a tiny city-state with a population, including foreigners, of 5.2 million. It is not too much of an exaggeration to say that everybody knows everybody else. Unlike in the big semi-socialist Western countries, where dictums issued on high for the entire country result in endless economic inefficiencies, one size can fit all in such a small place. Information does flow on a person-to-person level. Feedback, a necessary ingredient in economic efficiency, happens informally in small places.

Parenthetically, the Singapore model, contrary to the occasional statements of admiring leaders from China, does not scale. It works because it is small. China is too big to adapt the Singapore model, at least not without extensive modifications.

We think that small is a good antidote to democracies’ fatal attraction of populism. When countries are small, people can appreciate firsthand the stupidities of government. They instinctively know that they, the local people, must pay for everything their politicians so graciously give them.

The other antidote to populism is culture. Singapore’s core culture is Confucian Chinese, which stresses obedience to authority, conformity, hard work, and study. Just what you want in a banker. Just what an investor wants in an electorate.

Singapore is a major banking center and shipping nexus. Shipping and banking originate together. The latter is necessary to support the former. Its key location on the Straits of Malacca and now its centrally located modern airport give it a major presence in logistics. Its banks rode through the 2008 crisis without a hitch, as they did through the 1998 Asian crisis. Nonperformers are not a significant problem, and the super prudent Singapore government and prudent banking practices have made sure that nonperformers are not a problem.

Singapore, by the way, is not just in the money and shipping businesses. Almost 12 million tourists visited Singapore in 2010. Health care and biomedical sciences are also important. The recent addition of casinos—integrated resorts, as they are officially called in Singapore—helps alter Singapore’s traditional image of being dull and, in the case of Marina Bay Sands, offers some spectacular architecture.

Singapore is also an educational center. Singapore has a goal of establishing itself at a global schoolhouse, enrolling 150,000 foreign students by 2015. Education is a key industry for knowledge intensive money. Singapore’s bilingual educational policy—particularly the emphasis on English/Mandarin capabilities for its ethnic Chinese population—is perfectly suited to the needs of knowledge industries such as the global money business. Table 7.2 shows a quick summary of Singapore statistics.

Table 7.2 A Quick Summary of Singapore Statistics

Sources: IMF-2011 data

| General Government Gross Debt/debt/GDP | 107.6% |

| General Government Expenditure/GDP | 17.6% |

| Current account/GDP | 21.9% |

| GDP per capita (US dollars) | $49270 |

| Consumer price inflation | 5.25% |

| Unemployment rate | 2.03% |

| Official Reserve Assets (US dollars) | $244 billion |

| Population | 5.3 million |

The reader will view these figures and notice that the sovereign debt/GDP ratio is quite high and is quoted on a gross basis. So why am I recommending this country? The angel, in this case, is in the details. Singapore, as far as is known, has zero foreign sovereign debt. It generally runs a significantly positive primary budget surplus. But there apparently are three reasons for Singapore’s official gross public debt figures to be high. First, Singapore has a compulsory retirement scheme called the Central Provident Fund (CPF). All citizens and permanent residents contribute to the CPF. The government issues debt, which the CPF purchases. So far, this sounds like just another potentially bankrupt social security system. But there’s a big difference. The government then borrows the money raised via issues of nontradable Singapore Government Securities and puts it into two sovereign wealth funds, the Government Investment Corporation (GIC) and Temasek. GIC invests all its funds abroad. Temasek invests in Singapore companies and in foreign companies. The whole process could use more transparency—for example, it’s not clear if some of Temasek’s investments in government-controlled Singapore corporations are profitable—but overall, the system is totally different from Western pay-as-you-go systems that fund their own governments. Although the IMF doesn’t publish a net sovereign debt/GDP number for Singapore—it is curious that it does not—it seems clear that Singapore’s net number is way below the gross number of 100.8 percent.

Second, roughly 60 percent of public companies in Singapore reportedly have majority government ownership. These companies are not necessarily unprofitable but their debt is added to overall statistics of government borrowing.

Third, Singapore sells some government paper to offer liquidity in the local money market.

Being small brings its own set of problems vis-à-vis global capital flows. If the world “discovers” Singapore, like Switzerland (to be discussed) too much cash will flow in thus endangering local export industries. The money business may be Singapore’s most promising business but it is not the only business.

The Singapore dollar is managed by the Monetary Authority of Singapore (MAS) against an undisclosed basket of currencies. The country’s large foreign reserve position combined with its current account surplus and relative large foreign reserves suggest that the currency is a sound bet on a long-term basis. Right now, the markets seem to still put Singapore in the “risk-on” category. Great news for investors who think Singapore doesn’t really belong in this category.

Nevertheless, Singapore is currently running a CPI inflation rate in the 5 percent area. This is higher than the current rates in the deflationary West. The country’s high level of reserves, combined with this higher inflation rate, suggest that the Sing dollar could be allowed to appreciate further.

The risks for Singapore are its position in the entire global economy. Singapore is a child of globalization. Singapore is sensitive to economic events in China, the United States, and Europe. But we are not recommending Singapore stocks per se. We are recommending Singapore as a place to put cash and ride out the global storms. The reward, hopefully, will be a solid currency that appreciates as the Western currencies fall on hard times.

Conservative investors can park cash in Sing dollars and earn whatever meager interest rates are currently available and—sooner or later—own an appreciating currency.

For those who wish to take on more risk, there are some alternatives. One is Singapore REITs (Real Estate Investment Trust). Singapore has its own thriving stock exchange, and it is the home of a number of REITs. Unless there is a total collapse of the global economy and a massive global credit squeeze as in 2008, Singapore REITs offer reasonably attractive returns with a reasonable level of safety. Of course, vacancies are likely to rise in the coming months. With Singapore REITS you get returns currently of 5 to 7 percent in Singapore dollars plus you are long Singapore dollars. Again, there is the risk that in the event of a major global crash, Singapore REITs will decline in price as vacancies rise and rents decline in a major way.

A second, riskier alternative would be to buy shares in Singapore banks. Singapore banks are relatively well capitalized and carry reasonable dividends. They are not the large global banks; later in this chapter it will be explained why those should be avoided. Remember, the “raw material” of a bank’s business is money. The Singapore dollar, in our opinion, will hold its value if the dollar and the euro suffer a major decline.

As we said, Singapore is becoming the Switzerland of Asia. Switzerland, on the other hand, already is . . . Switzerland. Too bad everybody knows this. An investment is always less attractive when everybody knows about it. And in an age of massive global capital flows, Switzerland’s virtues almost become liabilities when the entire world, including ourselves, want to put money there and/or buy its currency. Highly prosperous Switzerland is synonymous with banking, sobriety, and a rock-solid currency.

Switzerland restores our battered faith in democracy, as this is one country that is fully democratic and fiscally responsible. You can carp about Singapore’s authoritarian side, but no such objections have been leveled at Switzerland. In fact, its federal canton system actually has features of direct democracy that would probably make James Madison cringe. Switzerland is living proof that our theory that the fatal attraction of populism will inevitably undermine functioning democracies is not always right. Thank goodness.

The similarities between Switzerland and Singapore are amazing. Both are small. Both have conservative, core cultures. Like Singapore, Switzerland is multiethnic and multilingual with German-speaking Swiss at 65 percent, French 20 percent, Italian 7.5 percent, and Romansh 0.5 percent. English is not a Swiss official language but it has widespread usage in Switzerland and to some extent serves as a link among the various ethnic groups. As is Singapore, Switzerland is a meritocracy and there are no downtrodden minorities demanding special treatment and more government services. The core culture is conservative and thrifty—in this case German-based, as opposed to Singapore’s Chinese Confucian. And French-speaking Geneva, it will be recalled, was the home of “fun-loving” John Calvin. This author can personally remember dining in Geneva and a dinner companion being berated by the waiter for not finishing her cheese. The spirit of John Calvin lives on!

Both Switzerland and Singapore require adult males to serve in the military. Both countries feel they need a strong military to discourage larger and, at least in the past, sometimes unfriendly neighbors. As we have argued, nobody likes money men, especially rich ones. In Switzerland’s case, the unfriendly neighbors were Germany, both under Kaiser Wilhelm II and later Adolf Hitler, and Italy under Benito Mussolini. The Nazis had a plan, never executed, called Operation Tannenbaum to invade Switzerland.

Switzerland’s educational system is world renowned. The university system is known for its research in the medical and science area. Several major pharmaceutical companies, including Novartis and Hoffman-La Roche, are based in Switzerland. The Global Competitiveness Report (GCR), a yearly report published by the World Economic Forum, in 2011–2012 ranked Switzerland as number one in the world. Singapore was number two! (Hong Kong, which we will discuss in the next section, was number eleven.)

Switzerland’s financial sector plays a central role in its economy with regards to labor, the creation of value, and tax revenue. The financial sector is responsible for roughly 12 percent of the gross domestic product and employs 6 percent of the workforce. Furthermore, this sector contributes to approximately 10 percent of the country’s income and corporate tax revenue. Switzerland’s general stability accounts for its international reputation as a preferred provider of financial services. Important competitive advantages are, for instance, its political constancy and the stability of its currency. Switzerland also plays a leading global role in asset management: roughly one third of all private assets invested abroad are managed by Swiss banks. Table 7.3 shows a quick summary of Switzerland statistics.

Table 7.3 A Quick Summary of Switzerland Statistics

Sources: IMF-2011 statistics

| General Government Net Debt/GDP/GDP | 25.9% |

| General Government Expenditure/GDP | 33.4% |

| Current account/GDP | 10.5% |

| GDP per capita (US dollars) | $83072 |

| Consumer price inflation | .23% |

| Unemployment rate | 3.92.84% |

| Official Reserve Assets (US dollars) | $479.8 billion |

| Population | 8.0 million |

As can be seen, the numbers shout out financial prudence, low debt, and wealth. Switzerland’s statistics are consistent with its image.

The Swiss franc, like gold, has been seen as a traditional refuge against monetary instability. As can be seen from the chart below, the monetary base of Switzerland virtually flatlined from 2002 to 2008. The Swiss franc has a record of constant appreciation against the euro and the dollar. Inflation has centered in the zero area.

But on September 6, 2011, the Swiss did something very un-Swiss. In response to an avalanche of incoming funds fleeing the euro crisis and pushing up the Swiss franc, Switzerland effectively devalued its currency and pegged its currency to the euro at SF 1.20 = 1 euro. The SNB had concluded that the rise in the franc had put Swiss industries in an intolerable position. The SNB threatened to buy “unlimited” quantities of foreign currency to push down the value of the franc. The money business had to take a back seat to the rest of the economy. But after this announcement and the SNB began buying currencies, the monetary base leapt upward. The SNB, the world’s paragon of monetary virtue, had just done its own quantitative easing. See Figure 7.1.

The franc peaked in August 2011 as the market began to react to comments from the Swiss that a peg might be coming. Investors who bought the Swiss franc in August could have been down as much as twenty five percent. For the moment, investors, who had looked to the Swiss franc as a refuge in perilous times, were handed huge losses. The Swissy, as the franc is sometimes called, had tanked big time.

So why should anyone consider parking money in Swiss francs or going long the currency? Several reasons can be given in response to this. First, the worst in terms of currency depreciation is probably behind us. Second, the Swiss tradition of financial soundness, low government involvement in the economy—all the things that made it number one in the GCR report—have not gone away. This intervention was not a Keynesian Bernanke type of stimulus. It was almost a “wartime” response to an external event. Third, it seems inconceivable that on a long-term basis the Swiss franc’s fate will be tied to the euro. Unless of course the euro transmogrifies into the New Deutschmark.

In the case of Switzerland, because of the troubles with UBS in particular in the 2008 crises, unlike Singapore we would avoid the Swiss banks themselves.

Put money into an entity that since 1997 has been part of authoritarian still officially communist China? Isn’t that crazy? Maybe not.

Hong Kong became a British colony in 1840 and was returned to China in what is now called the Handover in 1997. Hong Kong operates under a “constitution” called the Basic Law hammered out in negotiations between the British and the Chinese prior to the Handover. The Basic Law guarantees to Hong Kong basic freedoms including freedom of speech, English common law, property rights, and its own currency and banking system. “One country, two systems” is the operating principle and is guaranteed to stay in place for at least fifty years. The English language has an official status along with Chinese and is used in the courts, the financial sector, and the university system (but not unfortunately by the majority of taxi drivers). Contrary to the prognostications of the gloom and doomers at the time of the Handover, China has lived up to its agreement with the British and indeed the Comrades have respected the Basic Law.

Western visitors to Hong Kong have a hard time noticing much change since the Handover in 1997. Hong Kong has the freest media in Asia. You have to have a visa and fill out forms when you go from Hong Kong to China, as if you were entering a separate country. You can be annoyed by Falun Gong devotees in Hong Kong just as you can on the streets of New York. Judges still wear wigs and Hong Kong’s frenetic nightlife continues in full swing. The colonial era names remain in place as, for example, Victoria Harbour is still Victoria Harbour (except it is gradually disappearing thanks to its being filled in to create more buildable land. But that’s another story). Contrast this with India, where, for example, the venerable Prince of Wales Museum in Mumbai (itself formerly known as Bombay) has been renamed the Chhatrapati Shivaji Maharaj Vastu Sangrahalaya.

The Western press, including the local soft-left English-medium South China Morning Post, is constantly complaining that Hong Kong does not have universal suffrage. The departed British, who never introduced universal suffrage in Hong Kong themselves, have been among the loudest complainers. But James Madison might not complain. People worried in 1997 that the Peoples Liberation Army (PLA) would come marching in and turn off Hong Kong’s free market lights. But that hasn’t happened. The PLA regiment that is stationed in Hong Kong has remained quietly and decorously in its barracks, unlike some of the British lads stationed in the city in pre-Handover days who were known to occasionally misbehave on Friday nights while enjoying the dissolute pleasures of the city’s nightlife.

Hong Kong has, however, been invaded since 1997. Not by the PLA but by an “army” of populists who, if they had their way, would introduce a European-style welfare state and replace Hong Kong’s traditional and highly successful noninterventionist free market policies. It seems to be of no interest to them that Europe is going broke. Already, a minimum wage law has been put in place. Bankruptcy-envy is a phenomenon that the good Doctor Freud should investigate. But so far overall Hong Kong’s semi-democracy has managed to hold off the populists. Hong Kong now has a Legislative Council consisting of seventy representatives. Thirty-five are elected by universal suffrage from what are called geographic constituencies. The other thirty-five are elected in what are called functional constituencies. In a somewhat-opaque process, in those constituencies the representatives are elected by electors from professional associations.

The head of Hong Kong’s government is called the chief executive (the nefarious colonial term “governor” departed with the British). The Chief Executive (CE) is elected by a 1,200 member Election Committee that resembles in a vague way the American Electoral College in its early days. Critics say the Election Committee as well as the professional associations are dominated by wealthy individuals who yield to Beijing’s wishes. They are right. But from James Madison and investors’ point of view, this might not be such a bad thing. Beijing nowadays worries more about how to help its citizens get rich rather than imposing revolutionary doctrine. Louis Vuitton and Chanel have replaced Marx and Engels. Beijing has promised to give Hong Kong universal suffrage. Look for Beijing to procrastinate on that.

Finance accounts for over 25 percent of Hong Kong’s economy, with international trade and tourism next. Long gone are the low-wage factories, which have migrated to China and elsewhere. (Because this happened so fast in Hong Kong, it left an older, poorer population of ex-factory workers behind. This is a problem that the populists have exploited.) With the increasing wealth of the Mainland Chinese and their obsession with Western brands, along with the fact that there are no tariffs on imports into Hong Kong, the visiting comrades have turned Hong Kong into what might be called the Great Mall of China. Selling European luxury brands to an ever-increasing number of Mainland tourists has become big business in Hong Kong.

Hong Kong is one of the great financial centers of the world, along with London and New York. Banking, stock and derivatives trading, money management—Hong Kong does it all. The fact that the Hong Kong dollar has been one of the world’s predictable and reliable currencies has been a major attraction in making Hong Kong a major financial center and IPO center. Table 7.4 shows a quick summary of Hong Kong statistics.

Table 7.4 A Quick Summary of Hong Kong Statistics

Sources: IMF-2011 data

| General Government Gross Debt//GDP | 33.83% |

| General Government Expenditure/GDP | 20.3% |

| Current account/GDP | 5.3% |

| GDP per capita (US dollars) | $34,259 |

| Consumer price inflation | 5.3% |

| Unemployment rate | 3.4% |

| Official Reserve Assets (US dollars) | $244 billion |

| Foreign reserves per capita (US dollars) | $41633 |

| Population | 7.1 million |

Table 7.4 shows an economy that is fiscally prudent and with low government involvement but, like Singapore, with a current rate of inflation in the 5 percent year over year area. The question again needs to be asked why Hong Kong is running higher inflation rates than the United States and Europe. This takes us to the Hong Kong currency.

As with Singapore, locally the massive debt deflation is not operative as it is in the West. As far as is known, the banks and government regulations have been very stringent as far as down payments on mortgage loans go. The excesses that characterized the United States in 1996 are absent. Mortgage delinquencies at the local banks are currently running about 0.01 percent. Excess money creation by the Fed spills over into Hong Kong and, unlike the current US situation, does bring inflation.

The Hong Kong dollar is a unique animal in the world of international finance. At an official target ratio of HK 7.8 dollars to US 1 dollar, it is pegged via a currency board mechanism to the US dollar under a system known as the Linked Exchange Rate. This system requires both the stock and flow of the monetary base to be fully backed by foreign reserves. This means that any change in the monetary base is fully matched by a corresponding change in foreign reserves at a fixed exchange rate.

The net result is that technically Hong Kong does not have a central bank and its monetary policy, as it were, is determined by the Federal Reserve and the flows of capital in and out of the territory. The peg has come under fire in recent years because of what is regarded as an irresponsible monetary policy followed by the US and the increasing importance of the Chinese economy to Hong Kong.

Critics point to the fact that the current peg only dates back to 1983 and could be changed again. The following history of Hong Kong exchange regimes shows that on this point they are right. As can be seen, the peg has not been changed often but it has been changed.

| 1863–1935 | Silver standard with silver dollars as legal tender |

| 1935–1967 | Linked to sterling at one pound = HK $16 |

| 1967–1972 | Linked to sterling at one pound = HK $14.55 |

| 1972–1973 | Linked to US dollar with US$1.0 = HK $5.65 |

| 1973–1974 | Linked to US dollar with US$1.0 = HK $5.085 |

| 1974–1983 | Free float |

| 1983–present | US$1.0 = HK $7.80 |

Critics have argued that relatively high rate of Hong Kong inflation suggests that the Hong Kong dollar is undervalued. Raising the value of the currency would limit inflation. At least one prominent money manager in New York publically predicted in 2011 that the peg would be altered and the currency revalued after the new CE took over on July 1, 2012. So far he has been wrong.

There is no doubt that sooner or later the peg will be changed. But in our opinion it is unlikely to be changed in the very near future. Suggestions that the Honky dollar, as it is sometimes called, be pegged to the renminbi are off the mark. The renminbi is not fully convertible. For technical reasons alone pegging to the renminbi at the moment is not practical. Moreover, China has only recently arrived as a major player on the international scene. It does not have a long-term track record in terms of monetary stability. And China has further to go in terms of the rule of law. Pegging to the renminbi would be dangerous and impractical at this time.

Suggestions have also been made that Hong Kong adopt the Singapore system of setting the value of the Hong Kong dollar against an undisclosed basket of currencies. But what would be gained by this? Singapore’s and Hong Kong’s rates of inflation are similar. Moreover, eliminating the peg would move the exchange rate front and center and would politicize its level. To some extent, this unfortunately is already happening in Hong Kong. Singapore has been run by one party that has exercised firm control and can withstand populist heat. Hong Kong’s politics are still in the formative stage. This is a highly technical area, and one that the public is not likely to fully understand. There are great advantages in having the value of the Hong Kong dollar on “automatic” pilot, as it were. And Hong Kong’s role as a major IPO center in particular depends on the issuers being able to have confidence in the value of the funds they are raising.

Right now, the US dollar is a place of refuge in the global economy. The US elections, in theory, could bring a major change in fiscal policy. But that looks doubtful now. Hong Kong should not think about changing the peg until and if it becomes clear that the United States cannot reform itself.

Parking some money in Hong Kong dollars can be a good idea. Since the Honky dollar is currently pegged to the US dollar, the fate of the US dollar is your downside risk. For foreign nonresident holders of Hong Kong dollars, it doesn’t matter what Hong Kong’s inflation is. Unless of course you want to live in or visit Hong Kong. Only the US rate of inflation matters. If the US dollar goes into the abyss, then Hong Kong will surely have to think about ending the peg. Then the chances are the Hong Kong dollar will be revalued against the US.

Meanwhile, like Singapore, there are some local REIT names available for those who wish to take additional risk and earn a reasonable yield. The same risks apply to Hong Kong REITs as they do to Singapore. There are also a number of Hong Kong real estate companies but, as most of these now have major positions in China, we would avoid these.

Hong Kong also has a sound banking system. But we would avoid the Mainland banks as well as HSBC. Several other banks in Hong Kong that are local in nature (plus Standard Chartered) and carry yields may be worth a look.

Canada and Australia will be considered together since they have so much in common. Many have recommended these countries as a good short-term place to park capital and thus avoid the perils of holding US dollars. They could be very wrong even though the longer-term picture for these countries is bright.

I just don’t buy into the long-term commodity/resource scarcity story. The current world slowdown, particularly in China, is highly negative for commodities in the near term. Longer-term commodities will underperform in real terms because of ever-advancing technology. Unfortunately, today commodity/resource plays are China plays. And China has overinvested in a number of resources/commodities and is slowing down. Unlike the Sing and Honky dollars and the Swissy, on a near-term basis the Aussie dollar and the Loonie (as the Canadian dollar is infelicitously called) are unlikely to outperform the US dollar.

As mentioned, there’s no gainsaying that Canada and Australia are attractive on a long-term basis. It is tempting to include New Zealand in this discussion as well. But the white/Maori divisions in that country represent a complication not present in Canada and Australia, Australia isn’t called the “lucky country” for nothing, and Canada would be lucky too, if it weren’t for its lousy weather. They may not be such great places to park cash near term while waiting for the United States in particular to work through its coming budget crisis but they may great longer-term investments. Both might be great places to look for investments after the world is further into the big crisis that is currently unfolding.

Both Canada and Australia are former British colonies and as such have inherited democracy, the English language, British common law, and a respect for property rights and the rights of individuals. Both are predominantly European-origin countries without the populist threat of numerically important downtrodden minority groups demanding extra levels of government services (the English–French divide in Canada seems to be slowly disappearing). Both have enormous land areas relative to modest populations. The land areas are brimming with natural resources and, in the case of Canada, energy. Both have well-educated, intelligent populations well suited to competing in a global knowledge economy. Both are attracting high-quality Asian immigrants and, in the case of Australia, Asian students. (Australia may be about to acquire a new round of high-quality Greek immigrants as well.) And, as the accompanying numbers show, in terms of fiscal ratios like net sovereign debt/GDP, both have run reasonably conservative fiscal policies. The European disease, socialism, hasn’t totally infected these countries.

Tables 7.5 and 7.6 show a quick summary of Canada and Australia statistics. One major difference from Singapore, Switzerland, and Hong Kong: These countries’ foreign reserves are multiples of those for Canada and Australia. Considering their much smaller populations and size, it brings out my point that the Cash 2 countries are in a sense global banks. Places to hold cash. Australia and Canada in many ways are better places to look for long-term investments.

Table 7.5 A Quick Summary of Canada Statistics

Sources: IMF-2011 data

| General Government Net Debt/GDP | 33.1% |

| General Government Total Expenditure/GDP | 42.7% |

| General Government Structural Balance/GDP | −3.6% |

| Current account/GDP | −2.8% |

| GDP per capita (US dollars) | $50,496 |

| Consumer price inflation | 2.9% |

| Unemployment rate | 7.5% |

| Official Reserve Assets (US dollars) | $66.321 billion |

| Population | 34.4 million |

Table 7.6 A Quick Summary of Australia Statistics

Sources: IMF-2011 data

| General Government Net Debt/GDP | 8.1% |

| General Government Total Expenditure/GDP | 36.4% |

| Current account/GDP | −2.2% |

| GDP per capita (US dollars) | $66,371 |

| Consumer price inflation | 3.4% |

| Unemployment rate | 5.3% |

| Official Reserve Assets (US dollars) | $45.416 billion |

| Population | 22.4 million |

It seems almost a contradiction. The central banks are printing high-powered money with wild abandon, government budgets are out of control, and most of the governments of the advanced countries have unsustainable debt loads. Yields should be rising. Fixed income should be the last place anyone would want to look. Especially dollar fixed income.

But in fact, the opposite is true. Global supply exceeds global demand for tradable goods. The huge debt loads are forcing a retrenchment of spending, including that of government. The current buzzwords are deflation/disinflation, not inflation.

Advanced-country bond markets around the world currently divide up into two groups. First, there are countries under market attack, such as Greece, Italy, Spain, Portugal, Ireland, and even France. Second, there are those countries not under market attack—the United States, Japan, Germany, and even the United Kingdom.

Owning fixed-income securities in the latter group of countries seems like a sensible strategy so long as deflation/disinflation is in the air. It seems clear that of this group the United States will be the “last man standing.” A market attack on the United States will bring on a global financial Armageddon. Then you want to get rid of all your fixed-income securities.

Will anyone ring a bell that Armageddon is here? I doubt it. The US elections, however, could have been the bell ringer. It is interesting that the election of Francois Hollande in France has not rung a bell—yet. Hollande is pursuing an anticapitalist, anti–supply-side strategy including higher taxes on the “rich” and a reduction of the retirement age. One would have thought Hollande’s election would have brought about a collapse in French bond prices. It hasn’t happened—yet.

Now here are two thoughts. We associate higher levels of government debt and governmental defaults with inflation. Is it possible that government bond yields could rise to punitive levels as governments totter into bankruptcy while the overall economic environment continues to be one of disinflation? The near term forces of deflation including massive oversupply of many commodities and goods as well as debt deleveraging remain in place. In fact rising government bond yields and disinflation has already happened in Southern Europe. And would the yields on non-government bonds—particularly those of solid global corporations—trade below those of government yields?

That’s the problem for investors now. We have no history, no example of massive government (inflationary) money printing conflicting with massive global deflationary forces.

Not much to say here except AVOID for now. But not forever. As far as Europe goes, longer term, who knows. Europe is populated by intelligent, well-educated people. But they have been infected with socialism and populism. Can they rid themselves of this disease and enact real supply-side/structural reforms? Or will all of the intelligent and productive Europeans simply stop working (or leave), as they did in Ayn Rand’s Atlas Shrugged?

Europe has some great global companies especially in Germany, the United Kingdom, and France. They just happen to be headquartered in the wrong place. The legendary Mexican mogul Carlos Slim is already investing in Europe. Slim learned his investing from his father who began buying property in Mexico City in the height of the Mexican Revolution. People are always referring to the famous Barron Rothschild quote (although they never specify which Barron Rothschild) that investors should be buying when there is blood in the street. The Slims literally followed that advice. But for mere mortals, with regard to Europe, better to wait.

As far as European sovereign debt goes for the weaker countries, yes there will be opportunities—but not for amateurs, and not yet.

A comment on Treasury securities adjusted for inflation. The United States version of these is called TIPS—Treasury Inflation Protected Securities. Great concept. I don’t like TIPS for two reasons:

There are three ways to look at gold. The first is simply as an inflation hedge. In this view, gold is sort of an index of commodity prices. Here gold may be ahead of itself. For example since the gold link was terminated in 1971, CPI inflation index has risen 567 percent. From its $35 per ounce official 1971 price, gold has moved up roughly 4,600 percent. While the choice of beginning price is somewhat arbitrary in this calculation since the official price in 1971 was below market, the likelihood is that on a pure inflation basis, gold is currently overvalued. Moreover, in a period of near-term debt deflation in the advanced Western countries and Chinese slowdown as we are now in, gold as a commodity is likely to decline in price. No question if hyperinflation is on the horizon, gold will rally. But not yet. As mentioned, deflation, or at least a lack of significant inflation, is our near-term future.

Comparisons with the past for gold can be misleading. When gold was the center of the monetary order, it was the anchor, the constant. Of course, gold held its value. Today it performs no such role. In periods of financial stress when in theory people should be buying gold, they are sellers as they need liquidity. In periods of global expansion, gold becomes an attractive asset to hold. Many people argue that quantitative easing is releasing high-powered money into the system, which will then chase gold. I don’t see it that way. I think the high-powered money created is just sitting in the central banks as excess reserves. Debt deflation is a powerful force. Of course, the high-powered money won’t sit in the central banks forever.

A second way to look at gold is an attractive alternative asset and store of value for central banks and investors in a time of loss of confidence in the dollar and the euro. Under this view gold might play some role in a new international monetary system or as the basis for one of several future alternative currencies. A lot has been written about this. Under this view, gold presumably would have a higher value than under the first view but it is hard to come with some kind of valuation formula for this. Moreover, all of this, while it makes for interesting intellectual discussions, is somewhat “mushy” as an investment strategy. Despite what many believe is illogical, the dollar today is strong and the euro has held together. So long as the dollar and the euro hold together, gold will not be the refuge that its supporters believe it should be. A breakup of the euro could cause a rush into gold as an alternative. That would be bullish for gold. But I do not think the euro will break up. Yes, longer term, the ECB’s money printing will be inflationary. But not now as Europe careens into a recession.

The third way to view gold is to assume the classic gold standard will be revived. In that case, there would be a huge shortage of gold at current prices. Depending on what kind of gold standard would be adapted (e.g., full or partial backing for checking and currencies), a great deal more gold would be required. Since the supply of physical gold is highly inelastic, the only way to increase the supply of gold in monetary terms would be to increase its price by several multiples of where it is today. Most gold bugs implicitly assume a gold standard restoration. They are anticipating a monetary cataclysm to force this change. I would answer, maybe someday but not yet.

But remember from our discussion on the price-specie flow model. The gold standard doesn’t work if central banks can create high-powered money out of thin air in addition to holding gold. Frankly, it seems unlikely central banks will give up this power. Nobody needs a phony gold standard, and that’s what it would be if central banks still had money creation powers. Government demand management is considered a divinely appointed duty by modern economists, central bankers, politicians, and indeed electorates. They are not going to let go of that.

So buying gold in hopes of a restoration of a pure gold standard seems like a long shot. The gold standard would be wonderful, but it’s not likely to happen. The fatal attraction of populism makes it unlikely that democracies will ever allow a return to the classic gold standard. I am torn between a fundamental view that the historically successful gold standard should be restored vs. the unlikeliness that such an event would ever happen.

Keep in mind that David Hume’s price-specie flow model is not an investment scheme. It is an economic system with gold at the center. It equilibrated automatically the entire global system of trade. Surplus countries and deficit countries would be brought back into balance. Hume wasn’t a gold bug in the sense the term is used today. He wasn’t urging his followers to go out and buy gold. The classical gold standard is not a get-rich scheme. Restoration of this system will, in theory, bring about a major one time capital gain for gold holders. If the system is not restored, no capital gain.

As argued in the previous chapter, the more gold goes up in price and the more people are seriously considering giving gold a renewed monetary role, the greater risk of confiscation and/or punitive tax treatment of gold by governments whose monetary monopoly is threatened. Never forget Franklin D. Roosevelt’s 1933 Executive Order 6102. This forbade the hoarding of gold coin, gold bullion, and gold certificates within the continental United States, thus criminalizing monetary gold by any individual, partnership, or corporation. Ironically, Roosevelt made it illegal to own gold about the same time the Twenty-First Amendment made it legal to drink liquor. The majority of the country was more pleased by this latter action than displeased by the former.

Note that the government of India—desperate for money any way it could get it—recently doubled the import duty on gold. After huge protest and a twenty-one-day strike by jewelers, most of this tax increase was rolled back. OK, the government of India is not exactly a model of good governance. But the message is clear. Gold can be an easy target for governments.

One justification governments give when they institute measures to discourage their citizens from holding gold is that they want to redirect funds into “productive assets.” That’s what the Indian government said. What could be more productive for citizens than an asset like gold, which provides a store of value for their own savings? Doesn’t that fill a consumer need as much as a computer or a bag of potato chips? Providing a store of value is something government-issued depreciating fiat money generally does poorly or not at all.

My view of continued deflation/disinflation followed by inflation later makes for a complicated story. During the inflationary period commodity prices will rise, but we are not there yet. Near term, further weakness is likely to be exhibited in the commodity sector.

Longer term, my preference is not to buy commodities themselves but rather to buy the companies that make commodities more plentiful. Technology always comes along to enable a supply increasing response to higher commodity prices. We have seen this recently with horizontal drilling and fracking suddenly appearing to make oil and natural gas more abundant. The same in the agricultural sector, where genetically modified food and biotechnology have the potential to increase food output. The world’s not going to run out of anything. Technology will always come to the rescue. Commodity booms always reverse. This leads to a preference for companies in the oil service and oil and gas infrastructure sectors, the biotech sectors and in the mining equipment sectors. As mentioned, the greatest risk to companies in these sectors is mindless and exaggerated environmentalism and related Luddite movements.

Of course in a period of hyperinflation, in nominal terms commodity prices are likely to spike upward.

This asset class would include tech and nontech companies. It is attractive longer term because it has a significant chance of preserving wealth in a variety of economic environments. Here’s why:

Again, without actually picking stocks, I would like to review some areas to look for in global companies. First is technology, particularly American technology companies. This is what America does best. When it comes to pure tech, better to own an ETF or mutual fund on a long-term basis. Yes, you would rather own the next Apple or Microsoft. But who knows which company that is. And when tech companies stumble, the results can be ugly. Nokia is an example. To repeat, technology is driving human evolution and human progress. Telecommunications, computer technology, nanotechnology, biotechnology all fall under this category. The big global companies will do relatively well. The small tech companies are for specialists.

Second, there are the companies that cater to the consumer sector in the emerging markets. All those billions of nouveux riche ex-third-world consumers are filled with lust for Western products. Anyone doubting this should spend some time in Hong Kong and watch the hordes of Mainlanders line up behind velvet ropes at Louis Vuitton or Chanel stores. Or go to Macau and see how in one decade the gambling business has gone from a sleepy backwater to doing five times the volume of Las Vegas.

Third is agricultural stocks. As mentioned, while birthrates are collapsing almost everywhere, the world’s population is likely to add at least another billion or so people to the current seven billion. And they don’t want to eat rice anymore. As people get rich, they want meat and fish. And cows eat corn. Lots of it. Note I am not not forecasting an agricultural commodities price boom, although ag prices will have their bubbles. What I am saying is that technology is going to have to increase agricultural output. Organic farming is not going to do the trick. (In fact, because of its substantially lower productivity per acre and unsubstantiated health benefits, it could be argued that organic farming is environmentally harmful. But that’s another story.) The Monsantos and the Syngentas of the world are going to be needed to feed the world.

One point worth noting here. The United States, with its freedom of expression and information, sophisticated financing system, and superb higher educational institutions, has been the center of world technology development. It is no accident that Apple, Microsoft, Google, Facebook and so many other tech firms are American. Steve Jobs would have been crushed if he had grown up in China. It would be a global tragedy if in the coming crises a tax-hungry, regulation-infatuated US government undermined this.

From an investment point of view, there are several fundamental realities concerning banks that exist in virtually every country.

First, large banks will not be allowed to go bankrupt and they won’t be allowed to take risks and earn high rates of return. Governments won’t allow these banks to take risks since the governments will have to pay if, as in 2008, the risks turn out badly. I cannot argue with this government logic, by the way. If governments are going to socialize the risks, then governments should socialize the profits as well. Or, to put it another way, bank risks should be limited and bank capital should be enhanced to protect the governments from losses. Unfortunately, on a long- and short-term basis this makes for a rather unattractive equity outlook for global commercial banks. For a global bank, if it’s too big to fail, then it’s too big to sail. (OK. That phrase isn’t quite memorable but think of a better one.)

The failure of Lehman Brothers in 2008 and J.P. Morgan’s recent huge derivatives losses are two signature events. Regarding Lehman Brothers, the American regulators followed the free market, Austrian School prescription and allowed Lehman to go bankrupt. It was as if one hundred years of populist thinking and an ever-greater government role in the economy was suddenly forgotten. But not for long. The American officials quickly lost their nerve as they feared in horror that the entire global financial sector was lined up to go down next. Maybe after the financial sector completely crashed a new and better one like a phoenix would rise from the wreckage. But US Treasury Secretary Hank Paulson wasn’t going to take the chance and find out. I think he knew quite correctly that the American people—indeed, the entire world—did not want him to take that chance. We’ll never know what might have been. The Austrian school economists can write all they want. The global public and the economics intelligentsia have a closed mind on this subject.

Ramsey MacDonald, a now-forgotten British Labour Prime Minister in the dismal 1930s, once said that the financial sector is the nervous center of capitalism. No modern elected government anywhere can allow its financial sector to have a nervous breakdown.

But how do regulators draw the line between preventing global banks from taking undue risk and totally stifling initiative and innovation among these institutions? All of this keeping in mind that government’s implied guarantee to the large banks creates a major case of moral hazard. If the government is going to pick up the losses, why, bank managements may ask, not take more risks on less capital? Of course, that is what happened over the years.

Various approaches have been suggested to curtail big bank risk. The so-called Volker rule is one. Under this rule, big, publicly guaranteed commercial and investment banks shouldn’t be allowed to engage in speculative or nonhedged proprietary trading since the government has to pick up their losses if they lose. But then we have the spectacle of J.P. Morgan announcing a multibillion-dollar loss on what it considered a hedged trading investment. J.P. Morgan is considered by many to be the best run of all the large American banks. Its CEO Jamie Dimon is considered to be the most gifted bank executive, perhaps, in the world and one to rival the original J.P. Morgan himself. But here we have J.P. Morgan stumbling in a most egregious manner. And its gifted CEO proclaiming before Congress that he doesn’t really know what the Volker rule is. Of course Dimon was being disingenuous. The Volker rule, named after former Fed Chairman Paul Volker, supposedly prohibits banks from using depositors’ money to engage in speculative activities. What Dimon was really asking was “how do you draw the line between a normal bank hedging of its books and proprietary trading? Jamie Dimon before Congress essentially said he could not. Maybe nobody can. The Dodd–Frank bill (discussed below) includes the Volker rule, but the regulations on this have yet to be issued.

Over the years, large commercial banks gave the public an illusion that they were safe and protected by their governments. The banking crisis in 2008 shattered this illusion. The large global banks are now subject to tougher oversight by all bank supervisors. Governments and central banks realize that global banks are no longer their friends. These banks took high risks, distributed handsome bonuses to their star employees, and paid good dividends to their international shareholders. However, they came back to their governments to ask for support after serious losses.

A second approach to mitigating bank risk are the Basel III requirements. Bank supervisors realized the risk of commercial banks in the 1980s, when they implemented Basel Accord (known as Basel I). This bank supervisory standard linked capital to asset risk. Ultimately, the Basel I and later Basel II standards were failures. Basel or no, banks have gone down in every Western country, thus far (with the exception of hapless Lehman, which wasn’t technically a bank and therefore not under Basel) bailed out in one form or another by their regulators.

In 2008–2010, Basel III was developed by central banks via the Basel Committee. Two simple words can summarize Basel III: higher equity. Banks must have higher equity requirement to support their high-risk activities. The equity requirement in Basel III is around three times what is required in Basel II. Basel III becomes effective in 2013–2018. In this five-year period, all the banks, regardless of large size or small size, need to issue new equity to support their operation. Investors will have to be more patient if they want to buy bank stocks. There will be an enormous supply of new equity in the coming years.

Still, in view of what has happened in Europe and the looming sovereign debt crises in all the advanced countries, the entire Basel approach could be viewed as regulatory stand-up comedy. Government bonds are treated as risk-free assets, requiring little or no capital. As it turns out, in Europe today government bonds are frequently the riskiest asset banks can own.

An additional regulatory negative piled on to the US banks is the Dodd–Frank bill, or to call it by its proper name, the Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act. Passed in 2010 with the Volker rule and many of the Basel III rules included, its sponsors were none other than Representative Barney Frank and Senator Christopher Dodd, the two congressional leaders right at the top of the Fannie/Freddie legislative rogues gallery.

It would seem that the primary purpose of this bill is to tie up all banks with enough regulatory requirements so as to make the fulfilling of these requirements banks’ primary activity. Bankers who spend their time filling out government forms and worrying about being politically correct won’t have time for mischief making in the derivatives markets! Many of the requirements in the Dodd–Frank bill have nothing to do with banking but satisfy America’s insatiable need to protect women, consumer, and minority groups via government regulation.

I believe this bill will eventually be judged to be as harmful in its economics as was the Community Reinvestment Act, about which this book spoke earlier. The Dodd–Frank bill will add to banks’ cost of doing business and inhibit innovation. There’s an irony here. The larger banks can deal with regulations better than the smaller banks. There are economies of scale in hiring lawyers and accountants to deal with the unproductive task of complying with burdensome regulations. The too-big-to-fail big banks will benefit on a relative basis as compared to the “small-enough-to-die” small banks. In the future, talented young men and women aspiring to a career in banking will major in law and human relations, not finance.

It is interesting that one of the most disastrous regulatory decisions of the last decade rarely gets mention. In 2004, the Securities and Exchange Commission vastly liberalized the limits on leverage for the major American broker dealers. Goldman Sachs, Morgan Stanley, Merrill Lynch, Bear Sterns, and Lehman Brothers were allowed to increase their leverage by a quantum leap. And by 2008, they had done just that. What so many observers don’t seem to care about was that the government had sufficient power to regulate the financial system. But, in the case of the major brokers and also in the case of Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac, the government failed to use the powers that it already had. What America needed to regulate its financial system was a government with integrity and brains and not corrupt politicians who then went on to pass the giant legislative atrocity called the Dodd–Frank bill.

Many observers have also argued that the big banks are just too big to be managed well. This may be true, but I think it’s something for the market, not the regulators, to solve. The major corporations of the world get bigger and more global every day. Banks who service them have to be big and global as well. It may be that some of the functions of the big global banks should be divided up. Some of these functions, including derivatives and other types of proprietary trading, can be done by non-banks. This is already happening. Many Wall Street analysts are calling for breakup of the big banks on financial grounds. Fine. If the market thinks it’s a good idea, let the big banks split themselves up. This is one area where regulators should not tread.

A second important factor and potential negative for banks is money. A bank’s raw material is money. This book has spent a lot of time worrying about the possibility of inflation over the long-term as the result of current central bank policies. Banks can have real problems if inflation comes, especially if it is unexpected. Mess with a country’s money and you are messing with a country’s banks. But right now, with the central banks holding short rates at zero, you don’t need a Harvard MBA to be a banker. Borrow short, lend long.

A third negative factor regarding the big global banks is regulatory/legal. This factor became more prominent as this book went to press. The Standard Chartered case for me, at least, was a shock. The big global banks look to be the perpetual victims of what I would call “the bank protection business.” Bankrupt governments can now help themselves to bank profits, since bank regulations are now so complex and arcane that there is always grounds for a good lawsuit. The recent hold-up of Standard Chartered is just another chapter in what has become a very familiar pattern. Somebody sues a bank for something and rather than fight in court, the banks settle and essentially pay a protection fee so they can keep doing business. In the past in the United States, the banks have had to pay from time to time on alleged discriminatory lending practices by such organizations as the notorious ACORN (Association of Community Organizations for Reform Now). Thus, the banks were sued for underlending to minorities and then overlending after the 2008 crisis. The Community Reinvestment Act (CRA) in particular has been a useful tool for activists and their allies in government to extort money from ever-eager-to-comply bank managements.

Now things have gone international. HSBC and Standard Chartered are being accused of money laundering. They are, of course, paying up as fast as they can write the checks. The initial bravado exhibited by Standard Chartered’s CEO Peter Sands quickly evaporated when he was faced with the possibility of losing his bank’s New York license, guilty or not. “Your money or your life,” is not a pleasant choice when someone has a gun held to your head. Peter Sands proved to be no Jack Benny.

There are five unpleasant realities facing banks that make them easy targets for activist and governmental extortion:

The emergence of so-called emerging markets has been a major financial theme in recent years. Spreads on emerging market bonds have narrowed dramatically, fiscal houses have been put in order in many though not all countries and globalization has been a boon to untold millions of people in poorer countries around the world. The acronym “BRICs”—Brazil, Russia, India, China—has become a symbol of the new wealth that is being created. Symbols are important. Enthusiasts for Indonesia and South Africa and even Turkey have tried to get their countries’ names somehow incorporated into the BRIC acronym.

Advanced country investors should allocate part of their funds to these new markets. But keeping the following in mind:

China and India have a combined population of almost 2.5 billion people. You have to have a view on both to invest in emerging markets. Both countries are not simple stories. We’ve already discussed the flaws in these countries’ economic models in Chapter 3. Starting with China, we would say the following are general rules:

India from an investment point of view can be summarized in one phrase. Great companies, terrible government.

India is a frustration for investors. India has some of the best companies and managements in the world. India, unlike China, allows a free flow of information. India has a tradition of intellectual freedom and creativity, superior corporate governance, a world-class scientific elite and the use of English as the primary medium of corporate communications.

But as mentioned, as the world’s largest democracy, India is as vulnerable to the fatal attraction of populism as the advanced Western countries. Government expenditure is misdirected to welfare type rather than infrastructure expenditures. India’s inflation remains high, in part, because of government-imposed bottlenecks and lack of infrastructure. One reform after the other gets thwarted by state governments and vested interests. Government-run companies like the railroads and Air India continue to drain the government coffers with their appalling and chronic losses.

As mentioned, you cannot understand India and ignore its caste system. Many modern Indians don’t want to talk about it. They argue that it is rapidly disappearing and that the British exaggerated its importance. Maybe so. But the caste system has been a core feature of the dominant Hindu religion. India’s private companies are run by talented, well-educated, generally higher-caste professionals. But India’s democracy more and more is dominated by the less-educated, lower-caste groups who look to the government to equalize a playing field that has been unfairly balanced against them for over a thousand years. These lower castes have a legitimate grievance. But investors can’t be social workers. Fairly or unfairly, the upper castes are where you find the Indians loaded with talent. Moreover, India has had a tradition of Nehruvian socialism that, while intellectually discredited in some circles, still maintains a powerful hold on the country’s political process.

Investors who are surprised at India’s occasional irrational antipathy to foreign investors need to be aware of Indian history. The country was essentially run by a foreign multinational, that is, the British East India Company, for roughly a hundred years up until the assertion of full British Imperial authority in 1858. Old memories die hard.

Another point about India should be understood. The Republic of India today is but a (substantial) fraction of the Imperial Raj under the British. Raj India included today’s India, Pakistan, Bangladesh, and, from an economic point of view, Sri Lanka (Ceylon), Myanmar (Burma), Nepal, and Bhutan. Anyone with even the most cursory knowledge of economics would clearly see the tremendous advantages of a free trade arrangement among these countries. But India’s trade with its neighbors is extremely small. Politics, of course, is the reason. Post–independence Indian relations with its immediate neighbors has, shall we say, been less than cordial in most cases. Any opening up in the trade area would be a tremendous boost for the GDPs of India and its neighbors. That’s a no-brainer.

Indian stocks have rallied in 2012, much to my surprise. The talk of reform is once again in the air. But we’ve heard this before. There is still a good chance that India is headed for another foreign exchange crisis. I would be cautious regarding Indian stocks.

Brazil, it used to be said in Latin America, “is the country of the future and it always will be.” For the last few years, people stopped saying that as it looked like a new and fast-growth Brazil was emerging. In my opinion it’s a little early to start breaking out the champagne for Brazil.

Brazil, like India, has great companies with great professional managements. Brazil also has an inheritance of welfare state socialism—more the Continental Europe variety as opposed to the Nehruvian form (assuming there really is a difference). But it all amounts to the same thing—a hungry government looking to please its poor underclass rather than investors.

And Brazil has another similarity with India. Brazilian society can be divided by race as India is divided by caste. Over 50 percent of Brazil now is non-white, the bulk of African descent. The contrasts between the white/Asian groups where the professional, managerial class comes from and the non-white Afro Brazilians are stark using the usual metrics of education and family income. The level of race consciousness is not at the same level as caste consciousness is in India (or race consciousness in the United States), but it is there. (White) Brazilians make a big deal about how they are color blind and not like Americans. But most of the race mixing in Brazil occurred in colonial days when there was a shortage of white women.