$2 TO WIN ON NO.5

When the first bet was placed on a horse, and whether it was for money, ego, status or the horse itself, is unknown. But how bets have been made over the centuries is an interesting history.

The earliest bets in the context of racing were generally considered to be between two horse owners or two other individuals.237 Races were either quarter-mile sprints or multi-mile heats around a track. In colonial America, land was, first, too valuable and, second, too difficult to clear to devote space to an oval track. In fact, as in early Lexington, races were down existing streets or roads.

As racing became more sophisticated, jockey clubs were formed, oval tracks were established and the number of horses in a race increased (because the tracks were wide enough to do so). The rules for betting became more detailed as well.

The 1830 Rules and Regulations of the Kentucky Association in Lexington contained thirty-six paragraphs. Of these, nine, or a full 25 percent, regulated betting—and one prohibited gambling. For example, rule 24 provides that if both wagering parties are present, either may require the money be staked or shown before the race starts; if not, the bet may be voided. Or if a party betting is absent, the party present can go to the judges and declare the bet void unless some third party puts up the money wagered. On the other hand, no gambling was permitted on the grounds under control of the club, and a committee was authorized to employ police to arrest and punish anyone violating rule 34.238

Today, bet, wager and gamble are treated pretty synonymously; however, it is clear that in 1830 they had different or differing meanings. A bet or wager was considered to be a calculated and informed act by a gentleman knowledgeable about confirmation, breeding, jockey skill and other considerations that would go into deciding which horse should win. A gamble involved, and indeed might be entirely, the element of chance.

As frequently happened in the English language, there are two words for the same thing with different etymologies. Bet has a first known use of 1591 and may well have its origin in Saxony, in what became England.239 Wager goes back to at least the fourteenth century and is derived from Anglo-French wageure, showing the Norman French influence on our language. While the first definition is today’s common one, the archaic definition was to give one’s pledge to do something and abide by the result of some action.240 Thus, a wager was considered a promise to pay if a horse did not win.241

The dictionary takes a tiered process to arrive at the origin of gamble, referring to the word gambler and thence in turn to game, the origin of which dates to before the twelfth century and derives from Old High German and Old Norse gaman, pleasure or amusement.242 In other words, a gamble was not the considered judgement of an informed man but just a game of chance and thus had no place in the track clubhouse, which was open only to members in good standing.243

Finally, Kentucky’s current state constitution, when adopted in 1891, prohibited gambling but allowed for wagering on horse races.244

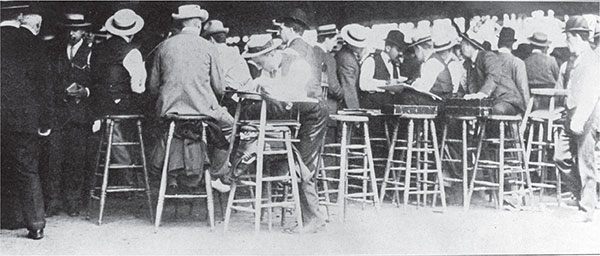

Bookmakers at a track. Keeneland Library.

This prohibition on gambling at the track only encouraged offtrack gambling. While bookmaking and bet takers operating to make a profit had been around since ancient Rome, bookmaking as a modern practice developed in England in the late eighteenth century and soon spread to the United States. The bookmaker seeks to maintain a “balanced book” of bets so that he will make a profit regardless of which horse wins.245

In the post–Civil War period, bookmaking in Lexington centered in its finest hotel, the Phoenix Hotel. By the 1880s, however, criminal elements were entering the picture and forming “betting rings” around the country. Not only were these “pernicious influences” sullying the pure wagering of gentlemen, they were also diverting money from the operation of the tracks. The Kentucky Association in Lexington amended its charter to permit Association-operated betting on the grounds of the track and at one place off the track as designated by the Association—no doubt that place was the Phoenix. The Association issued a public call to all tracks in the United States to do the same.246

Bookies and bookmaking now entered the track grounds, but it was not a pretty sight. They were described as being littered about the track grounds, their runners plying members of the crowd to go bet, running to the stables for any information and rushing back to their bookie, who could adjust his odds. Some stood under umbrellas to identify their location to bettors; sometimes the track would erect a tent to corral the bookies in one place.247 The 1894 new grandstand at Churchill Downs included twenty stalls for bookmakers.248

The grandest “bookie enclosure” in the country was Floral Hall at Lexington’s Red Mile. It is sometimes called the “round barn,” because horses were stalled there at times, even though it is an octagonal brick structure. Built on the community fairgrounds in 1882 as a floral display and exhibit facility, its center is open so judges could view all the exhibits on three levels and compare entries easily. Trotting-horse races began at the adjoining track in 1875; eventually, the Kentucky Trotting Horse Breeders Association acquired the track and Floral Hall. Betting followed the races, of course. When Lexington outlawed gambling inside the city limits in the late 1800s, the bookies had to leave the downtown hotels. Floral Hall, however, was just outside the city boundary; the track itself was not. The bookies moved their operations into the hall.249

The Kentucky Association adopted a similar strategy. While half of the track was inside the city limits, the final turn and home stretch were not, and the association built its “betting shed” near the final turn.250

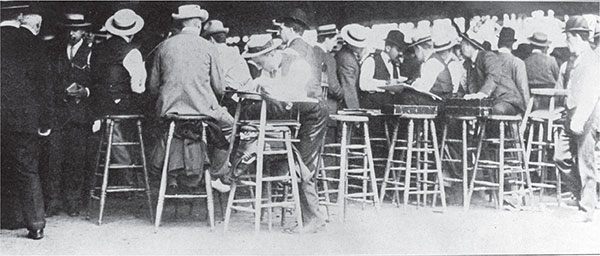

Bookmakers in the clubhouse. Keeneland Library.

Floral Hall, Lexington. Photograph by author.

Bookies would travel from track to track following the racing circuit. They began to form associations that would negotiate arrangements with tracks on their behalf. In 1891, for example, the Kentucky Association reached an agreement with the Western Bookmakers’ Association whereby the track was to be paid between $18,000 and $20,000 for allowing the Bookmaker’s Association to send fifteen to twenty bookies for the twelve-day spring meet.251

License fees and group deals were a good source of revenue not only for tracks. Individual bookmakers also could make serious money, particularly as they could become the favorite bookie for wealthy men and breeders, who would favor one man over the others. Bookmaker Robert G. Irving made $93,000 in 1887, for example, and George A. Wheelock netted $143,000 in 1888 after paying winning bets. Charles Riley Grannan from Paris, Kentucky, could sometimes make $20,000 to $30,000 on a single race.252

Raymond W. Kanzler wrote a retrospective for the Baltimore Sun in 1958 describing his experience with bookies at Pimlico. “They were gentlemen,” he wrote. “They dressed, spoke, drank and behaved in general like gentlemen.” Perhaps he was describing those bookies in the clubhouse. The bigger bookmakers had runners who scampered about the track seeking information on horses and jockeys, takers who calculated and recalculated odds, writing them on chalkboards behind the bookie and ticket writers to write out a betting slip for a patron. Bookmakers with more limited resources watched the odds boards of the larger operations and copied them.253

This method of betting is known as fixed-odds betting, in that the odds are agreed upon by bookie and bettor when the bet is placed, regardless of how the odds may change until the race is run. In contrast is pari-mutual betting, in which the final payout, and odds, are not determined until betting on a race closes. Thus a bettor may place a bet with 4–1 odds, only to find the odds drop to 2–1 at race time as others place bets on the same horse.254

The pari-mutual system of betting was invented by a Frenchman named Pierre Oller and introduced in Paris, France, around 1780. As opposed to betting against the bookie, a bettor wagers against all other bettors. At the conclusion of a race, the track takes its percentage, and the balance of the pool of money is divided by the total number of successful wagers. The beauty of the system is that the track knows it will get revenue, which can increase as the volume and amount of bets increase (as opposed to a fix fee from bookie associations), and any number of people can bet on the winning horse (as opposed to bookies, who stop taking bets on a particular horse to balance the book).255 As the progressive forces of social reform succeeded in outlawing bookmaking, the pari-mutual system was ready to take its place. Pari-mutual wagering was approved by the Kentucky General Assembly in 1918, although tracks had started using the system earlier.256

Keeping track of the bets and changing odds required manpower, as the early tallies were kept on chalkboards at the track. As popularity, and legality, increased, small machines—essentially early adding machines— were manufactured to do the work, and in big tracks were ganged to keep up and the machines began to be grouped in small buildings of their own. It was time for automation.

There are different stories on who invented the automatic totalisator machine. Kristina Panos gives credit to an Australian engineer, George Julius, who was actually trying to invent an election vote calculator, with the first commercial machine being installed at a New Zealand track in 1913.257 The American Totalisator Company, on the other hand, credits its founder and engineer Harry Straus and a group of American engineers with inventing and installing the first electromechanial system at Arlington Park in 1933.258

It may be the distinction that the Julius system was purely mechanical and operated like a complex grandfather clock, with levers and weights. When a bet was made, the betting agent would pull a level that tugged at one of many overhead wires. Each pull represented a bet. The wires adjusted wheels and gears that turned large wheels with numbers on them, which were visible through second-floor windows of a two-story betting house. The New Zealand betting house had thirty betting windows and thirty betting agents pulling levers for bets and horses.259

The ritual incantation “$2 to win on no. 5” had its beginnings with the functional limitations of these early mechanical systems. The data had to be entered in a precise order: dollar amount, place, horse. If a bettor gave the information to the teller in the wrong order, the teller had to wait and then enter it in the correct order or the bet would not register. There were limited opportunities to enter preset dollar amounts, usually two, five, ten and twenty dollars. A six-dollar bet, for example, was impossible. A bettor would have to make three two-dollar bets. Larger bets were taken at special windows. Even though most tracks paid the horses through fourth place in a race, the machine could handle only three places. Computing power had to be reserved for the unknown number of entries in a race, which was governed by the width of the track and the number of stalls in the starting gate.

The AmTote machine was operated by electricity, not levers and weights. AmTote also claims invention of the first automated totalisator system, the first dash/sell terminal, the first Windows-based tote system and, as of 2013, was venturing into wireless terminals, voice betting, Internet betting and Instant Racing—all of the modern, computer-driven betting systems and devices familiar to betters today. These innovations also made possible the almost infinite variations of betting among horses, places and amounts known as “exotic wagering.”260