MY OLD KENTUCKY TRACK

This chapter looks at, and for, the former Kentucky tracks that once thrilled to the pounding hooves of racing horses and the cheers of anxious bettors. It will not discuss the Kentucky racetracks that are in operation as of 2017. According to one researcher, there were at least twenty-two tracks in operation at one time or another prior to the Civil War, and at least another seven tracks in operation afterward that have closed.261 This list, however, is not complete. It was from a single source, and other research has revealed tracks not in the compilation. In fact, it is not certain that every racetrack, especially in the period prior to 1800, has been rediscovered.

THE FIRST TRACK(S)

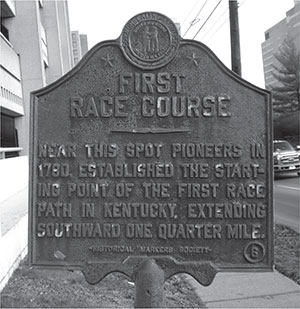

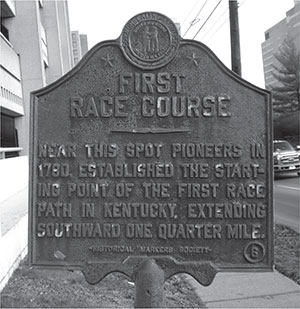

There are several contenders for the label “the first race track in Kentucky.” Early races were typically between two horses only and over a quarter-mile straight track, often a road. As Kentucky’s settlements evolved and land could be cleared, wider oval tracks came into use, permitting more horses to race at the same time.262 Also at this time, the threat of Indian attacks had to be eliminated. Thornton notes that at the end of a quarter-mile race near Shallow Ford Station in Mercer County in 1781, an Indian rose up out of the canebrake and shot the winning rider. He also states that there were three quarter-mile straight tracks between Harrodsburg and Boonesboro by 1782, which is to say, between the forts at those locations.263 A state historic marker at the top of the hill in the 300 block of South Broadway in Lexington states that it is located near the starting point for the first “race path” in Kentucky.264 The path, again, was a quarter-mile straight track running south. It should be noted that South Broadway is also Harrodsburg Road and thus in the shadow of the fort’s protection roughly thirty miles away. William Perrin states that Broadway was not “opened” until 1786, but as it was the way to Fort Harrod, there must have been some path.265

Kentucky Historic Marker of “First Race Course.” Photograph by the author.

EARLY TRACKS

An interesting and often repeated story is that of Colonel William Whitley, who established a track in Crab Orchard, Kentucky. It was the first oval track in the state and situated such that it encircled a small hill from which patrons could watch the horses run. Whitley was considered a philanthropist, patriot, poet and hero and was paid for his military service in land. At one time, he owned thousands of acres in Kentucky. Crab Orchard is on the Wilderness Trail from Cumberland Gap to Danville, about forty miles south of Lexington.266 English racetracks ran a race clockwise around a tract. Whitley was so anti-English that he started the American practice of running races counterclockwise to avoid imitating his former enemy.267 He was also a noted Indian fighter, having fought in some twenty engagements, including the one near Detroit in which he died in 1813.

A resort opened in Crab Orchard in the early 1800s that, in addition to a racetrack, featured a golf course, lake, poolroom, bowling alley, a dining room that could seat almost four hundred people and 250 hotel rooms. The Great Depression was a large factor in its demise.268

When Robert Sanders settled on his one-thousand-acre tract between Georgetown and Lexington in 1790, the area was still part of Fayette County. Two years later, it would be part of the newly formed Scott County. Sanders was wealthy and a horseman. By 1793, he was operating the county’s first racetrack and breeding thoroughbreds. Three more years later, he had built a five-hundred-bed hotel and tavern on his farm for the convenience of race-going guests.269 His meets were regularly advertised in the Lexington newspapers. Even though Sanders died in 1805, his sons evidently continued his equine and hospitality empire with races advertised as late as 1815.270

A late, great and short-lived addition to Kentucky racing was Raceland in Greenup County, known as the “Million Dollar Oval” for the expense to which Jack Keene and the Tri-State Fair and Racing Association went to build the track near Ashland in 1922. The association bought land from Keene and made him the general manager.271 A lake occupied the infield, and white fences faced with rosebushes lined the course.272 Its first race, the Ashland Handicap, was held on July 10, 1924, with 27,000 in attendance in the elaborate grandstand. By 1928, the association was behind in payment of a daily fee to the Commonwealth of Kentucky for the license to race; state authorities arrived to seize cash on hand. That left the track unable to make its mortgage payment, and the bank foreclosed. After it was sold in 1928, the new owners tried for several years to operate it as a fairgrounds, but, eventually, it closed permanently.273

In addition to the foregoing tracks, the following cities and counties in Kentucky had racetracks between 1800 and 1860: Glasgow, Camp Nelson, Maysville, Bardstown, Sharpsburgh, Eminence, Hopkinsville, Owensboro, Newport, Greensburgh, Elkhorn, Cynthiana, Burksville, Falmouth, Keysburg, Logan, Richmond, Russellville, Harrodsburg, Versailles, Henderson and Paducah,274 as well as Frankfort, Winchester, Shepherdsville, Harrodsburg, Columbia and Bethlehem in Henry County.275

LEXINGTON TRACKS

To say that there was a racetrack on every block of early Lexington would not be entirely accurate; but it would not be far from the truth.

The first racetrack in Lexington was not an officially sanctioned track. In fact, officials disapproved.

The custom had begun of racing on Main Street.

It is not known whether the practice was the result of any organized group. Thornton notes that Perrin’s 1882 History of Fayette County reports that a James Bray opened a tavern near the present Jefferson Street, which had been on the western edge of the town, and began running races.276

The Lexington Jockey Club was organized in 1787 to conduct races on an organized basis and according to its rules. Its races were run on the town Commons, a strip of land along the Town Branch, the middle fork of the Elkhorn River.277 One historian reports that the first race conducted by the club was held in October 1789 according to the “rules of New Market [sic]” (England).278 But if someone wanted to race and didn’t want to conform to the club’s rules, or wanted to race horses that didn’t meet the entry criteria, or the club was not conducting a formal meet at the time, there was always Main Street.

Lexington was formally chartered as a town under Virginia law by that General Assembly on May 6, 1782, providing for a board of trustees to govern the town, lay off streets and other powers.279 In 1790, the trustees approved the repurchase of two lots of land along Town Branch and the sale of unappropriated land at the east end of town to provide funds to pay for the land and to pay for “digging a canal to carry the branch straight through the town, also to have a row of lively locust trees planted on each side of the canal.”280 This provided a much better venue for horse racing. The hillside rising up from across the stream provided a good vantage point for spectators.

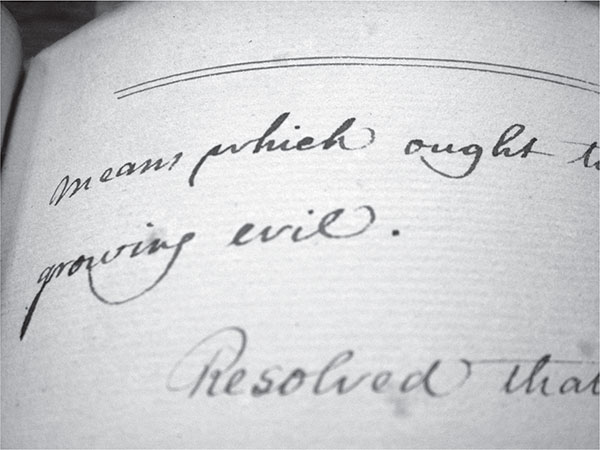

On October 21, 1793, the board of trustees for Lexington met to discuss the practice of horse racing on Main Street, which the trustees viewed as a “growing evil” and, considering that they were without sufficient authority to ban the practice without citizen support, passed a resolution calling for a public vote.281 Evidently, the votes favored a change, for on December 21, 1793, the trustees approved another resolution prohibiting the “running or racing of horses in the streets or highways within the limits of said town,” prohibited the showing of stud horses in same, established a schedule of fines for violations and relegated the stud horses to part of Water Street, along the

City of Lexington Trustees’ Minute Book. Photograph by author.

Town Branch creek west of Cross Street (Broadway).282 Racing was formally moved to the town Commons along the stream. Evidently, Lexington was not alone with this problem, for in 1793, the Kentucky legislature passed a statue banning horse races in streets.283

Illegal racing evidently continued, however, and the trustees on March 21, 1795, again considered a proposed law banning Main Street racing.284

To put this all in context, Lexington had a population of only 850 people in 1790.285

As noted earlier, a straight course for racing had been established on what is now South Broadway in the early 1780s, outside the platted town boundaries. Lexington’s formal town limits were platted in 1791, and its southern (southwestern) line was near present-day Maxwell Street, about where the Broadway tract started.286 By the time the plat was filed, however, racing interests had recognized the antipathy of the town trustees and moved outside the town limits.

Some time during the 1770s or early 1780s, Colonel John Todd conducted racing, likely another straight race path, on his property along the road to Georgetown, just west of Lexington, between today’s Short and Third Streets. Todd was the great uncle of Mary Todd, who married Abraham Lincoln. Unfortunately, Colonel Todd died in the Battle of Blue Licks in 1783. A widower, he left a young daughter as his only living heir; interest in racing there ended. As Lexington grew toward Todd lands and the property was subdivided and sold as house lots, the deeds frequently referred to the greater property as “the Old Race Field.”287

The Lexington Jockey Club now wanted to build an oval track, as the mile-long heats races that tested endurance were becoming more popular than the quarter-mile sprints focused on speed.

It constructed, or caused to be constructed, an oval track on a large and fairly flat piece of land farther west from Todd on the other side of the Georgetown Pike in what is now the rear of the Lexington Cemetery and extending north in what is today a small residential neighborhood. Races were conducted as early as 1795.288 This course was a one-mile oval and went by several names: the Williams (or Williams Brothers) Course, Boswells’ Woods and Lee’s Woods;289 but when the Jockey Club conducted its contests, it referred to them as being run on the “Lexington Course,” which may have been a designation of the racecourse itself as distinct from the total property.290 An advertisement announcing a forthcoming race in October 1795 noted, among other information, that horses were to be entered by the day before the race or pay a double fee to enter on race day.291 Ambrose reports that the Jockey Club ceased conducting race meets by 1823.292

For a year in the midst of this period, 1800, Sollow has compiled some interesting statistics. Among the heads of households in Kentucky, 92 percent reported owning at least one horse, and two-thirds had two or more horses. The average stable of a taxpayer was three horses; the number increased to four for landowners other than town lots, and slaveholders reported an average of five horses.293

In the early 1810s, there were races at the “Pond Course,” listed in one advertisement as being two miles from Lexington, but the compass direction is not given.294 One writer speculates it may have been on a farm two to three miles northeast of Lexington on the Maysville Road, now Paris Pike, known locally at the time as Wrights Pond or “the Pond.” Wright maintained a tavern and frequently held barbecues, music festivals and other events to increase the business in his tavern.295

Between 1823 and 1826, racing meets were held on private racing tracks around Lexington, including Henry Clay’s Ashland Farm.296

Another track during this period was at Fowler’s Garden. Opened by 1817 by Captain John Fowler, a local businessman, it lay on the east side of Lexington. Hollingsworth says it was about twenty-five acres in size.297 J. Winston Coleman, on the other hand, says it covered between fifty and seventy-five acres.298 Both agree that it had a racetrack, stables and related buildings, as well as facilities for fairs, livestock shows, political rallies, entertainments and exhibits “of all kinds.” Hollingsworth locates the facility between Main and Fifth Streets (south and north) and Walton Avenue on the east on to Race Street on the west. Being on the east edge of town, it was more accessible then the Williams track, and it became the social center of Lexington, one writer describing it as the “fashionable Country Club of its day” with dinners and dances. She notes that Town Branch flowed through the property as well and that the community celebrated the fiftieth anniversary of independence there.299 Hollingsworth notes that Fowler’s Garden closed around 1860.

In April 1826, members of the old Jockey Club met at Mrs. Keene’s Inn to start a new racing association. They entered into a subscription agreement to capitalize the new entity and agreed to conduct a preparatory race meet that June. Sixty subscribers paid fifty dollars each for one share in the new Kentucky Association for the Improvement of the Breeds of Domestic Stock. On June 8, a three-day meet began, running over the old Lexington Course. The race the first day was a three-mile run, the second day a twomiler and the third day more than one mile, with the horse carrying the best of the three wins as the purse winner. The third day also saw a “handycap” race. Over a great distance, age and weight carried mattered little; but on a shorter course, different weights (typically lead bars in saddlebags) were assigned according to the age of the horses.300

The Kentucky Association held its August race meet in 1826 at the Williams track, and racing appears to have continued there through 1830; but it also appears clear that the Association intended from the start to develop a new track under its ownership.301

The reason for that decision is not clear. It could simply be a desire to own the land. There does not seem to have been any disagreement with the owners of the Williams track as racing there was permitted for four years. There may have been some geographic defect or defect in course design; but in all events, it appears the search for a new site began early.

On July 7, 1828, the Association purchased more than fifty-seven acres from John Postlethwaite on the northeastern edge of town, at the east end of Fifth Street, close to the northernmost platted street. This site would be much more accessible to the residents of Lexington.302 The purchase was an “insider” transaction, as it would be known today, since John Postlethwaite was both the seller (with his wife) and a member of the board of trustees for the Association. However, his ownership was publicly known, and the price must have been fair for the other trustees to agree.

A week later, on July 15, the Association purchased all or a part of Out Lot 18 within the city limits. Described as twenty poles by forty poles, the lot was 330 feet by 660 feet at the south end of town and lay the entire length of Lexington from the new track site.303 The intended use of the lot is unknown, and Ambrose does not mention it. In the Lexington platting scheme, small in-lots were clustered around the Commons and were intended for residences, while the out-lots were intended, at least at first, to be agricultural, where residents would grow crops or keep stock. The Town Branch flowed through the lot; perhaps it was intended as pasture and corral for horses coming to race.

That summer, construction began on the new, one-mile oval track laid out in a modern flat design. Spring of 1829 saw the first races. A grandstand was erected in the center of the infield the following year with a view of the entire track, and the first formal meet was held in 1831. Admittance to the track was free, but admittance to the grandstand (and no doubt the reason for placing it in the infield) was a twenty-five-cent charge.

In 1834, an adjoining ten-acre parcel was purchased for the track, and in July 1836, four more acres were added, bringing the area to more than sixty-five acres. The Association enclosed the entire property with a wood-plank fence.304

The location of the Kentucky Association racetrack would have been just east or northeast of Fowler’s Garden, and Hollingsworth implies that the KA track became the focus of horse races while the garden stopped races and focused more on being the community entertainment center and fairgrounds.

Racing continued at the Kentucky Association course through 1898, including one meet held while the Confederate army occupied Lexington; but a national financial panic, the opening of competing tracks and financial problems caused the track to close. For several years, crops were grown in the infield and certain trainers leased the track as a training facility.

In October 1903, Captain Samuel S. Brown from Pittsburgh purchased the property and began a series of improvements. The first grandstand was torn down to open the infield, as were many sheds and outbuildings along the back side. A new grandstand with a two-thousand-spectator capacity was built along (and outside) the home stretch, and the clubhouse was substantially renovated. A new paddock barn with fourteen stalls was added as well as a “betting shed” that had stations for up to sixty bookmakers.

The moribund Association revived and held its first race at the new facility in May 1905 with a six-day meet.

By 1907, Brown had died and the Association, newly reorganized, purchased the property from his estate. Admission was one dollar for gentlemen and half that for ladies; daily programs were ten cents. The next year, the pari-mutual wagering system was introduced to the track.

Racing continued into the 1930s, but financial pressures resulting from the Great Depression forced its closure, with the last race run in 1933. Negotiations over several months resulted. In 1935, the federal government purchased the land for just over $67,000 for use as a federally funded housing project, and buildings and equipment were auctioned to the public.

At this same time, thoroughbred owners and breeders, deeming the old track too expensive to revive, withdrew and formed a new association. After purchase of the Keene farm on Versailles Road, it called itself the Keeneland Association and began development of the present Keeneland Race Course. As a lasting connection with the past, Keeneland purchased the old Kentucky Association gates for its entrance and adopted the “KA” logo of the old association as its own.

In 1850, the newly formed Kentucky Agricultural & Mechanical Association was incorporated in Lexington for the purpose of holding annual fairs, exhibitions, livestock shows and, with yet another track, racing and trotting meets. It purchased land south of the Maxwell Springs property on the south side of Lexington between the present Limestone and Rose Streets.305 This sounds very much like the activities carried on at Fowler’s Garden and suggests that this new track and exhibit area may have replaced Fowler’s Garden and led to its closure.

An 1877 map of Lexington shows the former Fowler’s Garden area as having been subdivided, the Kentucky Association track as partly within and partly without the city limits, by then a radius of one mile from the courthouse (thus permitting gambling outside the boundary), and the “Lexington Trotting Park” in the southeast corner. This track was operated by the Lexington Trotting Club, which was established in a meeting at the Phoenix Hotel in 1853.306 The Maxwell Spring property is labeled as the “City Park.307 Although the Red Mile Trotting Track was established in 1875, it is not shown, nor is Herr Park, which would be outside the city limits.

A remarkable one-man story lies just south of a historic section of Lexington and across from the University of Kentucky, where there was once a farm called Forest Park. The land lay just outside the mid-nineteenthcentury city limits of a one-mile radius from the courthouse but inside of the first tollbooth on the way from Lexington to Nicholasville.308 According to an 1891 map of Lexington and Fayette County surveyed by W.R. Wallis, which shows, inter alia, tollbooth locations, the booth appears to have been approximately where the present Cooper Drive intersects with South Limestone, although there were no crossroads in the vicinity at this time. The map does show Virginia Avenue almost at the city limits but close enough thereto that no farm would exist between the street and the line. Therefore, Forest Park was between today’s Virginia Avenue and Cooper Drive, north and south, respectively, and Limestone Street and the railroad, east and west.309

Lexington Fairgrounds. Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper, Lexington History Museum, Inc.

In 1851, a veterinarian originally from Canada named Dr. Lee Herr came to Paris, Kentucky, to begin his practice in horse country. At some point, he began owning and trading in trotting horses and developing his own ideas about breeding and training, using the public roads of Bourbon County as his training tracks because there were no trotting tracks in the United States yet.310 Just after the Civil War ended, Herr sold one of his horses for the then large sum of $10,000 and used his proceeds to buy Forest Park and move to Lexington.

Based on Forest Park, Herr expanded his breeding training program, while maintaining his practice (which kept him in good contact with other horsemen) and built the first trotting track on his farm. A writer for the Lexington Leader credits Herr with “introducing into the state the trotting horse” and notes that “there was no man in the state who had established a trotting stable for schooling trotters for track purposes until Dr. Herr.”311

Not only did he use his track for training, Herr at least as early as 1866 also began holding trots races on his farm and inviting the public and other competitors.312 This was, of course, a convenient way to advertise his horses and train them under actual race conditions. An article in the Lexington newspaper in 1872, at perhaps the peak point of trotting races at the Herr Track (the Red Mile Trotting Track was not established until 1875), reported: “Pretty soon the fine horses began to arrive with their fine looking drivers sitting behind them in shining, dainty looking buggies. There was no bell to tap, no officer to order up the horses, as it was simply a meeting of young gentlemen to see who of them had the best horse, and amuse themselves and each other by driving in a trotting race on which no money was bet and no pools were sold.”

The article reports that there were five entries, and due to the narrow width of the track, only three could line up in the first rank and the other two behind. Just as they lined up to start, a “herd of mares” ran across the track. As the reporter mentions that two entries contended for first place “all the way around,” it can be taken that it was an oval track. There were two heats run with the same entries. After the races, the drivers repaired to town, no doubt for a celebration.313

Unlike the Kentucky Association races, which followed something of an annual schedule of spring and fall meets, racing at Forest Park seems to have occurred whenever there was interest. Just the next month, the same newspaper reported on more trotting races at the Herr Track, noting that they had become weekly events attended by the public that afforded “pleasant amusement to our young men, without being demoralizing in their tendency.”314 In that case, the first race was the best of three one-mile heats and the second the best of five one-mile heats, thus giving the length of Herr Track from start to finish.

Racing continued at least into the 1880s, but by 1884, one of Dr. Herr’s sons published an announcement for a turkey shoot at Forest Park.315

Dr. Herr died in 1891, and his will provided that all of his property be sold, which was conducted on the premises over two days. The stock and land were auctioned the first day and the personal property and house contents the second. A large crowd attended. The land was in two sections. The main farm (and likely the track) of 163 acres was sold first, followed by a 50-acre plot “next to the city.”316 Heretofore the location of Forest Park and the Herr Track has only been located between South Limestone Street and the railroad track outside of the Lexington city limits. However, the street and railroad track parallel each other to the county line and leave many acres of possibilities. The newspaper article announcing the auction, however, gives an important clue that leads to the actual location of the farm. The article states that the farm is “inside” or town side of the first tollbooth. That information was important to potential bidders and the estate, because it announced that no one would have to pay a toll to attend the auction. It also sets an outer limit to the farm location.

The 1891 Wallis Map of Fayette County locates the toll stations.317 A cellphone application marries maps with global positioning system (GPS) and has done so with the Wallis Map. By traveling over relevant roads in the vicinity of the indicated station, it has been determined that the toll station stood approximately at the intersection of South Limestone and an interior University of Kentucky road called Farm Road, just slightly south of the present Cooper Drive.318

Kentucky Association Track gate post at Keeneland Race Course. Bill Straus.

Dr. Herr’s heirs bought both tracts. Within two years, the fifty acres had been subdivided into residential lots with the street named after Lexington’s newspapers—Leader, Press, Transcript and Gazette—perhaps in a bid to get more publicity from the press.319

The 1907 Sanborn Map of Lexington shows the Association thoroughbred track on the northeast corner of the city and the Red Mile Trotting track on the southwest, and all tracks previously described developed into residential or business purposes.320

In addition to the racing tracks, either publicly or privately owned, many breeders and trainers had tracks on their farm used for their own purposes. Henry Clay’s track at Ashland Farm is described in the chapter on Clay and the Madden family track on Hamburg Place in the chapter on Forgotten Farms as representative samples of private tracks.

LOUISVILLE TRACKS

As happened in Lexington and other communities where the desire to race outpaced the development of racetracks, races in Louisville were first conducted on a downtown street, in this instance Market Street as early as 1783, just five years after George Rogers Clark founded the town.321 Likely this was the early quarter-mile straight track type of race. It is not reported when racing on Market Street was discontinued nor what town officials thought of the practice, but certainly by the time the state law banning racing in the streets of towns was passed in 1793, it would have been discouraged.

There also appears to have been racing on a track near the end of Sixteenth Street called the Hope Distillery Course with multi-mile heats running in at least the 1820s. Races were also held at the grounds of the Louisville Agricultural Society in the 1830s, near the present site of the Louisville Water Company.322

A racecourse had been constructed at Shippingport, a peninsula jutting into the Ohio River just slightly downriver from the new town by 1805.323 Shippingport as a community was chartered in 1785,324 so it is possible the impetus for a racetrack resulted in racing there at an earlier date than 1805, again, potentially as a result of the state law.

To a Louisville citizen or visitor today, it is unimaginable that a racetrack could be built on what is now Shippingport Island at the Falls of the Ohio with the falls on the river side of the island and the Louisville and Portland Canal with its dam and locks on the town side; but when Shippingport was established, the canal had not been dug and would not be for fifty years. In the beginning, Shippingport and its ship docks was the departure point for goods sent south to New Orleans and coming north on the Ohio, just as the town of Louisville performed the same function for river traffic coming south on the Ohio or going north. Shippingport, in fact, almost eclipsed Louisville in community size and volume of business as Kentucky’s most important port. A six-story flour mill was built there in 1817 and the Napoleon Distillery located there.325 It also had the advantage of being outside Louisville city limits and any ban on gambling on horse races.

The track was a part of the Elm Tree Garden, which featured a platform three hundred feet in circumference encircling a large elm tree with a tavern. It overlooked mazes and puzzle gardens and, of course, the racetrack. It is easy to imagine a great day at the races, lingering at a table outside the tavern on the platform, watching the horses run with the Falls of the Ohio as a background. The community also had a three-story hotel with large balconies off the rooms.

Progress, however, was the demise of the Elm Tree Track. The digging of the canal in 1825 cut off the new island from the mainland and allowed ships to bypass its Shippingport’s dock facilities. The community went into decline along with its businesses. When Louisville incorporated as a city in 1828, it included the former Shippingport community within its bounds. Further widening of the canal over time (today at five hundred feet) and the erection of an electric plant took more land, and the flood of 1937 devastated the area. The federal government acquired all private land in 1958 in the final expansion of the canal and functionally ended Shippingport as a community.

Before its end, however, Elm Tree Race Track produced a famous jockey of its own. Jim Porter was born there in 1810 and was a thin, sickly child. As a result, at age fourteen, his weight was low enough to allow him to become a jockey. For three years, he rode at Elm Tree. Then, at seventeen, he experienced a growth spurt, which left him at seven feet, eight inches tall, NBA size for the early 1800s and very much too big to continue riding competitively. He became famous as “The Kentucky Giant” and, trading on his fame, opened a tavern near the canal, being successful enough to build an eighteen-room house with ten-foot-tall doors and personally sized furnishings.326

These various efforts to establish a local track resulted in the creation of the Louisville Association for the Improvement of the Breed of Horses, which copied the Lexington entity’s rules and bylaws, holding its first meeting at Washington Hall on November 5, 1831. A committee was appointed to locate land for a racetrack. A year later, just over fifty-one acres were purchased at what is now Seventh and Magnolia Streets, but which in 1832 was well away from the town. A large grove of oak trees on the property led to the new facility being called Oakland.327

When the first race was held the following year, Oakland Race Course was considered “one of the most handsome sporting venues in the country, welcoming even the ladies with a furnished room and private pavilion.”328

The “greatest race west of the Alleghenies” was held at Oakland on September 30, 1839. Promoter Yelvefton C. Oliver arranged a match race between Wagner, an 1834 colt out of Virginia who dominated racing in the South at this time, and Grey Eagle, who was foaled in Lexington in 1835 and who had run the fastest two miles in the United States. The purse was a stunning $14,000 to the winner. An estimated ten thousand people attended, including Henry Clay. The hotels and lodging houses were filled to overflowing, and even the branches of the oak trees were packed.

The race was two one-mile heats, and Wagner won both. A rematch was called for and run five days later at the same track for a $10,000 purse. This time, each horse won a heat; but Grey Eagle broke down in the second heat, ending his racing career. Both horses went on to successful careers at stud, and their progeny continued their competition. Cato, the enslaved African American jockey who rode Wagner to victory, was given his freedom for his successes.329

Racing continued at Oakland Race Course through the 1840s, but after 1850, there is no further mention of the track in Louisville newspapers and it was closed.330 The grounds served as a campground and cavalry remount station for the Union army during the Civil War and thereafter fell into disrepair.331

References have been found to two other early Louisville tracks, but very little information is readily available. Beargrass Creek Race Track ran from as early as 1808332 to at least 1823. John James Audubon famously attended a July Fourth celebration at the park that involved horse races and much eating and drinking. W.S. Vosburgh mentions that Greenland Race Track existed in Louisville but was “never popular” and abandoned around 1869.333

The Woodlawn Race Course has already been mentioned in the chapter about the Triple Crown races in the context that the Pimlico Race trophy was originally the prize for winning the feature race at Woodlawn. The track was established near the Louisville and Frankfort Railroad in 1859 for easy access of guests to the track from the train.334 In 1858, a flag-stop station was constructed at Woodlawn, and passengers were charged fifty cents for a nonstop ride to the track. Even after Woodlawn track closed, the railroad operated the stop until all stops were eliminated about 1935.335

There are few descriptions of the facilities at Woodlawn. The clubhouse is said to have been built with thick brick walls, the rooms were spacious, and there were ornate mantelpieces. The clubhouse is shown on a map in 1858 near where Ashland and Perryman Roads are today. There is a small (and telling) burial ground for African American jockeys who died as a result of racing accidents.

The Louisville Daily Courier reported that the spring meet in 1862 was cancelled due to “bad management.” By fall, however, “important alterations” had been made to the facilities and a new agreement was made to bring food and drink to the meet, perhaps correcting the aforesaid management problems. The Civil War was raging, and the Woodlawn track was soon affected. After the Battle of Perryville on October 8, 1863, near Richmond and east of Lexington, wounded Union soldiers were transported all the way to Louisville. Woodlawn Race Course became a camp and mustering-out post for soldiers. John Scheer states that racing was “reasonably uninterrupted” by the war, which seems a hopeful statement that would still leave Lexington’s Kentucky Association track as the only one to conduct regular race meets during the conflict.336

After the war, Woodlawn was a popular locale not only for horse racing but also for fairs and political rallies. It may even have contributed to driving the Greenland Course out of business in 1869. Interest in horse racing was waning in Louisville, though, and even Woodlawn had to close in 1870. There would follow a five-year gap when there was no active racetrack in Louisville.337 Today, the area of the former track is part of the city of Woodlawn Park.

While Churchill Downs was conducting thoroughbred racing at its track, Colonel James J. Douglas established Douglas Park as a venue for pacing and trotting horses in 1895. He selected property near the present Standiford Field Airport and constructed a one-mile oval track with banked turns, a large grandstand rivalling that of Churchill Downs, stables and a clubhouse.

He timed its opening meet to occur when the national Grand Army of the Republic held its convention in Louisville.338

The track infield featured extensive flowerbeds and a lake. The feature race each year was the Kentucky Handicap, and the winner’s name was spelled out in flowers in the infield.339

Douglas Park enjoyed success at the start with its trotting and pacing races, but by 1906, is was forced to close. Six years later, it reopened as a thoroughbred venue. In 1918, Churchill Downs acquired Douglas Park and converted it into an exercise and training facility. Over the years, demolition removed some buildings, others were destroyed by fire. Churchill began selling off portions of the Douglas property in the 1950s; by the end of that decade, all equine-related activity had ceased.340