HENRY CLAY, HORSE BREEDER AND RACER

Henry Clay, well known as the Great Compromiser, was the politician and statesman who almost single-handedly preserved the Union from early division and, in some estimates, pushed back the eventual Civil War over slavery thirty years. He ran for president five times and famously said, “I’d rather be right than president.”

But outside of a comparatively small covey of Clay cognoscente, his expertise and extensive involvement in breeding and racing thoroughbreds at his home estate of Ashland is little known. His principle biographers mention his involvement with horses but downplay his role.

David and Jeanne Heidler, for example, set forth his growing number of horses owned from the tax rolls between 1799, when he owned two horses— likely for personal use—and 1808, when he owned more than thirty horses, by then clearly in excess of those needed for personal transportation. Indeed, they note that the increase was reflective of “a growing passion” for horse racing, but they give the statistics more to demonstrate Clay’s increase in income and wealth than as a comment on his entry into the horse business.341

In Robert Remini’s extensive biography of Henry Clay,342 a painful search of the index reveals no entries for horses or horse racing. Instead, the short relevant entry is found under “Henry Clay, characteristics, as cattleman and farmer.”343 Instructive of the treatment of Clay as horseman is the following:

Clay also experimented with sugar beets and different grasses for pasture only to decide that the native bluegrass occupied a superior class by itself. In addition, the farm produced some tobacco, corn, wheat and rye.…Hogs, goats, cows, mules, and horses were raised by the hundreds at Ashland.… Over the next several years he began to breed Maltese jackasses, Arabian horses, Saxon and merino sheep, and English Hereford and Durham cattle. He imported cattle from abroad, and his racehorses were so superior and earned him so much prize money that Clay built a private racetrack at Ashland.344

It is understandable that Clay’s biographers wanted to focus more on his political and diplomatic career, and to a lesser extent on his family; but burying his extensive equine activity among the hogs, mules and sheep does not give a true portrayal of Clay the horseman.

In contrast stands the excellent study by Jeff Meyer in the Kentucky Historical Society journal.345 Meyer examines not only Henry Clay’s activity but also that of his family for two more generations to describe the Clay legacy. Meyer notes that eleven Kentucky Derby winners can trace their lineage to Henry Clay horses, even though the first Kentucky Derby was not run until almost a quarter century after Clay’s death.346

Henry Clay purchased his first stallion in 1806 and was entering his horses in thoroughbred races by at least three years later if not sooner. He established his breeding and training program at his Ashland estate, located just outside Lexington on the east—at its largest, it was more than six hundred acres. It lay between the road to Richmond and one of the roads leading to the Kentucky River opposite a small waterway called Tates Creek. At the time, all major roads outside the Lexington city limits were owned and operated by private toll road companies, and tollbooths were erected every five miles. Clay’s farm had tollbooths along each of the boundaries, but it also extended inside the locations of the toll gates such that he could go to and from town without incurring a charge. For those familiar with Lexington, the innermost boundary was about present-day Rose Street at the very western edge of Clay’s Lexington, and the outer limits extended along Tates Creek Road to Lakeshore Drive, thence along Lakeshore and around in a northerly line inside Lake Ellerslie to Richmond Road.

As much as Clay loved his public life in politics and government, he loved his retreats, some voluntary, some forced, to Ashland, writing that he was “getting a passion for rural occupations; and feel more and more as if I ought to abandon forever the strife of politics. I would not be unhappy if a sense of public duty shall leave me free to pursue my present inclinations.”347

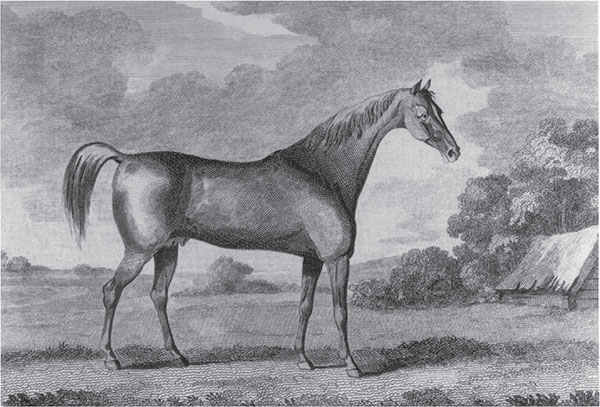

The story of Henry Clay’s first stallion is interesting not only for the horse itself but also for an innovation by Clay and his partners in the horse. The horse, called Buzzard, was purchased by Clay and four other men for the “extraordinary price” of $5,500 in 1806.348

The practice at the time was for the purchaser of a stallion to do so for the purpose of breeding only to his own mares. This may have been their original intent, but by 1808, Clay and his partners had, in essence, invented the modern stallion syndicate by owning the horse jointly and were advertising Buzzard to stand at stud for a forty-dollar fee.349 Equine law attorney Richard Vimont described this syndicate and the horse in a speech at the Kentucky Horse Park on the opening of a special exhibit of Clay horses in 2005.350

Buzzard was bred in England and had a very successful racing career there, winning thirty-four races between 1792 and 1794.351 After he was retired to stud, his progeny won more than one hundred races in England between 1799 and 1805; the next year, a Buzzard filly won the Oaks Stakes, the greatest of the races for fillies in England. In the early 1800s, he was purchased by Colonel John Hoomes, a Virginia breeder, and brought to stand at his stud farm in Bowling Green, Virginia. Following the breeder’s death in 1806, his estate put the stallion up for sale.

Buzzard. Photograph courtesy of Ashland, the Henry Clay Estate.

Meyer calculates that the $5,500 sale price would be worth about $67,000 in 2003, which sounds low for a well-performing stallion in today’s prices; but it should be known that the horse was blind in one eye, had a dislocated hip and had to be walked through the mountains from Virginia to Lexington at the age of somewhere around nineteen.352

Within a year of arrival in Lexington, Clay and his partners devised the syndicate format of the stallion owners having the right to breed their own mares and also share in the breeding fees payed by other mare owners. For those familiar with breeding agreements today, a fee can be either on a “live foal” or not basis, with the fee for the former generally being higher, as it involves the right to a successive breeding if a live foal does not survive. In the Clay syndicate, according to Vimont, the breeding was on a “no live foal” basis, but the mare owner, if he still owned the same mare a year later, could have a second attempt.

Buzzard’s career as a stud in Kentucky ended with his death after two years; but the syndicate model designed by Clay and his partners was used in the thoroughbred industry for more than one hundred years.353

The follow-up question, of course, is how well did the Buzzard offspring lines do? As noted earlier, Ashland only follows mare bloodlines, and two of Clay’s major mares will be discussed shortly. But the Pedigree Online Thoroughbred Database follows both sire and mare lines. Based thereon, every one of the horses running in the 2017 Kentucky Derby, including eventual Triple Crown winner Justify, can claim linage from Buzzard. It does take eighteen to nineteen generations (depending on age at breeding, etc.) to reach all the way back, but each of the horses was a Buzzard progeny. Further, each horse’s pedigree traces to either Mr. Prospector (bred 1970) or Native Dancer (bred 1961) or both, and both of those sires are descendant from Buzzard.

Henry Clay began racing his horses in 1809 and at least by 1810 was racing his Buzzard progeny. He joined the Lexington Jockey Club in 1809 and campaigned his horses at the Jockey Club Williams Track. By 1830, he had formally established his Ashland Thoroughbred Stock Farm and began an aggressive program of acquiring additional stock, frequently with partners, and breeding to improve his lines. He began his own stud book and recorded the stallions and mares, their foals and racing records.354

In 1845, three horses arrived at Ashland Stud as political gifts to Clay: Margaret Wood, Magnolia and Yorktown. These three are generally credited with establishing the “extraordinary success” of Clay’s breeding program and produced at least twelve Kentucky Derby winners.355 Three of the runners in the 2017 Kentucky Derby trace their lines back to Margaret Wood and Magnolia: Girvin, Hence and Classic Empire.356

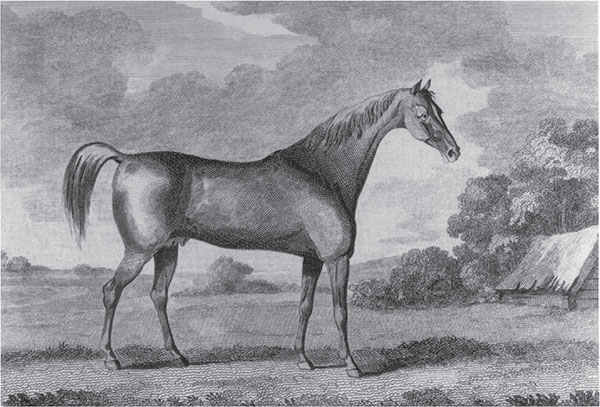

Photograph showing the trees (bottom center) outlining the former Henry Clay training track. Lexington History Museum, Inc.

To give some context to these political gifts, Clay had just lost his 1844 race for president the prior year.357

Margaret Wood would be a successful horse for Clay on the track and in breeding. She is in the pedigree of four nineteenth-century Kentucky Derby winners.

Magnolia became one of the most successful broodmares in the country. All thirteen of her foals were winners, and one of them, Kentucky, was thought to be the best racehorse ever foaled in America. Her nickname was “The Empress of the Stud Book.”358 Henry Clay’s son John took over the thoroughbred operations, and the last foal he bred from Magnolia was Victory by Uncle Vic, son of the famous Lexington. John Clay raced the horse lightly over the next several years and in 1873 George Armstrong Custer purchased Victory as one of his mounts. Custer was riding Victory on the day of the Battle of the Little Bighorn. The horse’s fate is unknown.359

After Clay’s death in 1852, John continued his operations at “Ashland-on-Tates Creek Farm,” while brother James purchased Clay’s house and about half of the farm. He rebuilt the house and, after a trip to New York, became interested in trotting horses. He purchased Mambrino Chief for the high price of $4,000 and brought him to Kentucky. He laid out a mile track on his portion of his father’s farm, along the Richmond Road, and started the process of introducing harness racing to Kentucky in 1854. John innovated breeding thoroughbreds to trotters, earning a reputation for scientific practices and for establishing a new breed, the standardbred.360

Following James Clay’s death in 1864, his widow sold the estate in 1866, and for fourteen years it was the campus of Kentucky A&M, the early name for the present University of Kentucky. The college relocated to its Euclid Avenue campus in 1879, and the farm was leased out.361

Finally, in 1882, Henry Clay McDowell and his wife, Anne, daughter of Henry Clay Jr., purchased Ashland and began restoring the house and grounds to a working equine operation again, possibly building a third racetrack on the property. He was already an established standardbred breeder and a fan of coaching.