HOW GOOD INTENTIONS ALMOST KILLED RACING

The old aphorism has it that the road to hell is paved with good intentions. In the ending decades of the nineteenth century and early decades of the twentieth, two movements collided, the effect of which was to almost kill thoroughbred racing in the United States: the Progressive or Social Gospel movement in America and the Jersey Act in England.

The Progressive Era is generally considered to have begun in the 1880s and lasted through the passage of the constitutional amendment giving women the right to vote in 1920, finally ending with the repeal of Prohibition. The Social Gospel progressives in particular sought to combat what they considered to be the negative social effects of industrialization: political corruption, saloons, gambling and prostitution. They elevated the American tradition of making one’s way by good, old-fashioned hard work and were appalled at the prospect that a few well-placed bets on the right horses could result in wealth.170

To take a view of the scope of the issue, in 1897, there were 314 thoroughbred racetracks in the United States, in addition to the standardbred tracks.171 The issue for the social reformers was not horse racing as such, but that there was gambling—and not so much gambling at the tracks, as there was a modicum of regulation by track authorities there. At first, bookies and their touts roamed the grounds. By 1891, Churchill Downs in Louisville set up three stands and confined the bookies there on penalty of losing permission to operate at all.172 Even the tracks, however, were not immune. In 1894, the operators of Chicago’s Washington Park closed it down because of the “degeneration of racing from a harmless and high-class sport into a species of gambling.”173

The real problem was seen to be the offtrack betting parlors where auction pools were sold. An auction pool was a wagering system whereby each horse in a race in turn was auctioned off to the highest bidder, and when bidding ceased, the remaining horses, if any, were grouped and auctioned as the field.174 More than one pool would be auctioned for a race if there was sufficient interest. In this manner, a bettor might spread his risk by buying different horses in different pools. The resulting pool of money, after the house took its charge, went to the holder of the winning ticket for that pool.175 In addition to the family suffering resulting from money lost by the bettor, these establishments sold strong drink and offered other entertainment, such as billiard tables to divert customers between races. They came to be known popularly as “pool halls,” and the name “pool” came to be associated with the game.

The reformers’ strategy was that, if betting were outlawed, the tracks would close and so too would the pool halls.

In 1898, New Jersey passed laws banning both gambling and horse racing. Not even August Belmont could prevent New York from outlawing gambling in 1908. Tracks and bettors turned to oral betting (the laws banned betting tickets), but further legislation attacked that practice. Finally, New York beefed up its law by providing that the officers and directors of a track could be fined and put in jail if any betting was found at their track.176 The tracks closed.

Almost every state in the country enacted similar laws, and by 1908, the number of thoroughbred tracks had fallen by 90 percent to only thirty-one. By the 1920s, only three states allowed legal betting at racetracks—one of which was Kentucky.177

Not that Kentucky was immune to the reformist movement. In 1908, Louisville passed an ordinance outlawing bookmakers, and Churchill Downs had to scramble to find pari-mutual wagering machines to hold that year’s Kentucky Derby.178 Racing interests in the Kentucky House of Representatives used a parliamentary maneuver to block a vote on a proposed five-cent tax on wagers.179 A bill to outlaw pari-mutual wagering was before the General Assembly in 1924, and it easily passed the House but lost, 24–10, in the Senate. Racing was retained in Kentucky by all of 10 votes.180

The defeat was attributed in large part to the strength and political power of the Kentucky Jockey Club, discussed in more detail later. At one time, the club was alleged to have some thirty legislators on its payroll.181 The Louisville Courier Journal opined that the “Kentucky Jockey Club, supported by the American Book Company, maintains a sinister but effective control of legislation in Kentucky.”182 The American Book Company was a trade association or union of bookmakers.

In 1927, betting was a key issue in the governor’s race, with each candidate taking clear but opposite stands on whether to ban gambling. As James Duane Bolin describes it, it was candidate “Beckham or betting.”

Longtime Lexington Democratic political boss Billy Klair, strongly connected with the central Kentucky racing interests, took a public position for the first time in favor of the other party’s candidate, Flem Sampson, who favored betting. Sampson won.183

Earlier, Kentucky had established the State Racing Commission in 1906 to regulate racing.184 It soon moved to outlaw bookmaking in favor of pari-mutual wagering. In 1906, there were twenty-six licensed (by the track) bookies working the Kentucky Derby at Churchill Downs.185

Through all of this political turmoil, it is not surprising that changes were also happening at the Kentucky tracks and were centered on the Kentucky Jockey Club.

Jockey clubs were originally comprised of racehorse owners and breeders, not riders. The first in Kentucky was the Lexington Jockey Club, organized in 1797.186 Its purpose was to “improve the breed” and bring some order to horse racing in Lexington, the town trustees having banned the practice of racing on Main Street. Henry Clay was a founding member. It built a new racetrack, the first oval in Kentucky, on property west of what is today Newtown Pike. The Lexington Jockey Club was something of a mutual association, and it made rules for what jockeys should wear, when and by whom horses could race, etc. It ceased operations and racing around 1823.187

In the next evolution of jockey clubs, they became stock associations, which is to say they raised capital to build tracks and facilities by the sale of shares of stock. The Kentucky Association, which succeeded the Lexington Jockey Club, was organized in 1826 and capitalized at $3,000 through the sale of shares at $50 each. A club room was established in a local hotel, the Phoenix, and only members could enter. This sanctuary would move to the association track when the clubhouse was build. Again, only members could relax in the clubhouse and watch races from there, as opposed to mingling with the crowd on the rail. Now, however, membership in the club was open to anyone who could buy a share, total membership being limited by the number of authorized shares.188

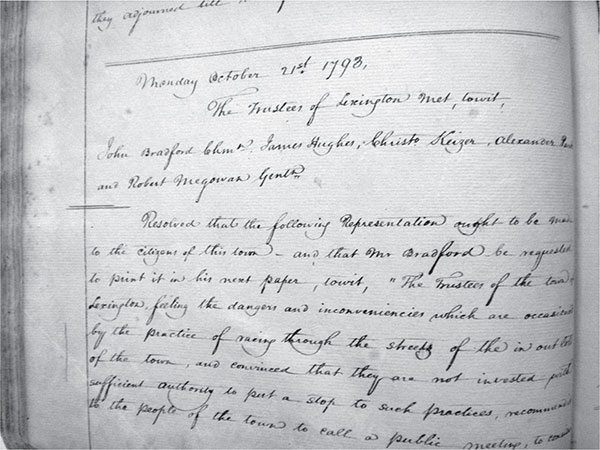

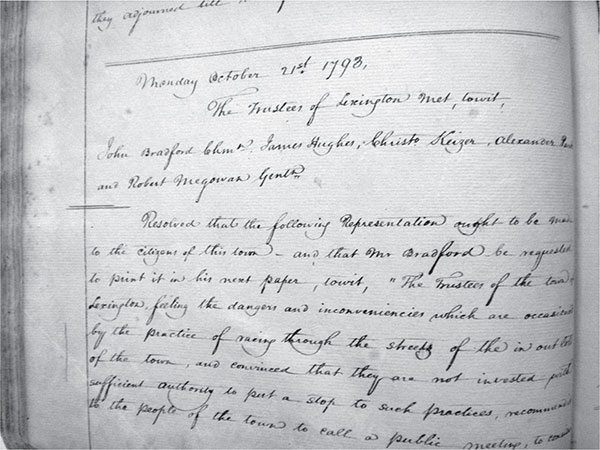

City of Lexington Trustees’ Minute Book. Photograph by author.

As with any other enterprise, clubs and tracks had varied economic success. By 1894, the Louisville Jockey Club was deeply in debt and was sold to a syndicate of “gamblers, bookies and businessmen,” thus effectively putting the foxes in charge of the henhouse.189

In time, it too would be sold. In 1918, a new corporation was formed called the Kentucky Jockey Club to “bring business efficiency” to racing in Kentucky and to act as a “further aid to a thoroughbred industry under siege.”190 It was capitalized by the sale of $1 million of stock to businessmen and horsemen. One major investor was both, John E. Madden.191

The new Kentucky Jockey Club quickly set about purchasing the state’s top tracks and, if the experience of Kentucky Association shareholders is any guide, the tracks were acquired by the exchange of stock in the new entity. By the time the spring racing season was underway, the KJC owned the Lexington track, Churchill Downs, Douglas Park (also in Louisville) and Latonia (Covington) racetracks.192 It exercised such control over Kentucky racing that it became the target of anti-trust charges, which it successfully defended.193

By 1927, it had added Fairmount Park in Illinois (East St. Louis), and Lincoln Fields and Hawthorne tracks, both in Chicago.194 If it is correct that only three states permitted legal racing at this time, the Kentucky Jockey Club controlled the top tracks in two of those three states.

The Kentucky Association, Inc. was incorporated to buy back the Lexington track, but the KJC continued to operate the track.195 The KJC was reorganized as a holding corporation called the American Turf Association, reflecting its multistate operations in 1927. During the Great Depression, all of its tracks except Churchill Downs closed, and in 1950, it became Churchill Downs, Inc.196

The closing down of racing in all but three states led to a tremendous drop in the value of racehorses. With few places to race and no purses to win, there was little reason to breed more horses. One exception for wealthy American horsemen was to ship their horses to England and continental Europe, where, to the consternation of the English horsemen, the American horses began to beat English thoroughbreds and win races. To make matters worse, the influx of horses flooded the English equine market and caused prices to drop.197

To protect both their egos and their wallets, the English responded.

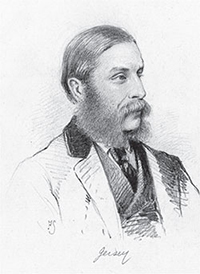

Victor Albert George Child-Villiers, the seventh Earl of Jersey, was one of the stewards of the English Jockey Club, which maintained the General Stud Book for British and Irish horses.198 Only horses approved for entry in the book could be called thoroughbreds in its jurisdiction. In 1913, he sponsored an amendment to the registration rules that the press nicknamed the “Jersey Act.”199 The new rule read: “No horse or mare can, after this date, be considered eligible for admission, unless it can be traced without flaw on both sire’s and dam’s side of its pedigree to horses and mares themselves already accepted in earlier volumes of this book.”200

The American stud book was not started until 1873, many decades after the British book, and therefore many of its records for the early part of the nineteenth century were incomplete. Other records had been lost or destroyed during the Civil War. As a consequence, it was extremely difficult for most American horses to meet the “without flaw” standard and qualify for registration, relegating them to the status of “half-breeds” or worse. A horse could still race, as the Jockey Club did not govern the English tracks, but it was worthless as breeding stock.201

The Seventh Earl of Jersey. National Portrait Gallery Picture Library (England).

To gauge the impact of the Jersey Act, as the rule came to be known, such great horses as Man-o-War, Triple Crown winner Gallant Fox and all descendants of sixteen-year sire book champion Lexington were not eligible to be registered.202 In fact, the majority of American horses were ineligible.203 Many American horsemen began to sell their thoroughbred stock.

One of the most noted horsemen and breeders in American was John E. Madden in Lexington, Kentucky. He founded his farm, Hamburg Place, with the proceeds of the sale of his horse Hamburg in 1897. Within only a few years, the farm grew to more than two thousand acres.204

Madden was of the opinion that when others wanted to sell, he should buy. For example, in 1912, Colonel E.F. Clay, owner of the renowned Runnymeade Stud, sold his entire stock of thirty-five mares, yearlings and sucklings to Madden. Included in the sale was Clay’s half interest in the stallion Star Shoot. Later that year, Madden acquired the other half interest in the stud.205

Star Shoot became the star of Hamburg Place. Having been bred only twenty-eight times in the last year of Clay’s ownership, the stallion was bred ninety times by Madden. That first crop yielded fifty-two named mares and thirty-six champions. Star Shoot was America’s leading sire for five years between 1911 and the year of his death in 1919, including champion Sir Barton.206 John Madden ranked first or second as the leading breeder, both in terms of races won and money won by horses he bred from 1917 to 1928.207

American racing rebounded from the prohibitive laws and social attacks and was thriving again in the 1930s as laws changed and tracks opened or reopened. American racing and breeding interests continued to complain about the Jersey Act and advocate its repeal. Finally, and quietly, the British Jockey Club revoked the Jersey Act language in its regulations and substituted text that a horse “must be able to prove satisfactorily some eight or nine crosses of pure blood, to trace back for at least a century” and to “show such performances” of its family on the racetrack “as to warrant belief in the purity of its blood.” This had little effect on American racing, which had risen to world dominance; but it cleared many champions and their get for inclusion in the British stud book.208