Histories of early Auckland say little, if anything at all, about duelling. It’s almost as though the thing has been hushed up. Yet you have only to read early newspapers to learn that ‘affairs of honour’ – as duels were euphemistically called – were by no means uncommon in pioneer Auckland, perhaps because of the presence of armed forces in the capital.

Fortunately, in 1895, an anonymous Herald journalist decided to fill this gap in the annals of the city by preserving for posterity the story of these duels and what lay behind them. He wrote a special article on affairs of honour, blending the reminiscences of old colonists still alive to tell the tale, with surviving written records gathered by trawling through newspapers of Auckland’s first decade. The outcome was a lengthy serialised article in the Herald entitled ‘Affairs of Honour in the Olden Time’. This treasure trove makes for absorbing reading.

Because private combats using lethal weapons to settle a quarrel or point of honour were usually confined to the upper classes in the Old World, it seems odd that duelling should have taken root in unaristocratic New Zealand. But the very fact that duelling continued in the highest circles of society in western countries gave it a kind of pragmatic sanction throughout the early nineteenth-century world. The famous 1804 duel between two heroes of the American War of Independence, Colonels Aaron Burr and Alexander Hamilton, who later became bitter political enemies, served as a model for lesser men to emulate. So did the well-publicised duel that took place two years later, between two aristocratic British cabinet ministers, George Canning and Robert Stewart (Viscount Castlereagh).

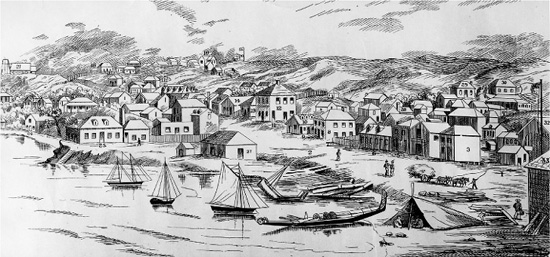

‘Kororareka with a fleet of American whalers in the harbour.’ The beach on which Polack and Turner fought out their duel is shown in the left foreground. J. B. C. Hoyte, undated water-colour. AUCKLAND CITY LIBRARIES, NEG. C101.

That the first duels in New Zealand should have taken place in Kororareka (later Russell) in the Bay of Islands is scarcely surprising. Before New Zealand became a Crown colony, Kororareka was notoriously lawless. So much so that in May 1838, the more respectable settlers there, who had already condoned the horse whipping of debtors and the punishment of offenders by the application of three coats of tar and feathers, felt compelled to go even further. They formed a Kororareka Association, to protect property, curb ship desertion and generally promote law and order. That each member was required, under Rule 13 of the association, to provide himself with ‘a good musket and bayonet, a brace of pistols, a cutlass, and at least fifty rounds of ball cartridges’ seems to show that a vigilante group had emerged prepared to enforce its own brand of rough and ready justice.

In a community under arms a resort to weapons to settle private differences was not, surely, unexpected. The 1895 Herald article records that ‘three affairs of honour’ took place in the Bay of Islands in pioneer days. The flavour of these quarrels is given by the account of the famous showdown on Kororareka beach between Joel S. Polack, a hot-tempered Jewish trader, and Benjamin E. Turner, a local grog-seller. What caused this quarrel is unknown. But the Herald article succinctly conveys the nature of the clash and its outcome. Turner, it reported, ‘got shot in the elbow’, while Polack ‘received a token of remembrance in the cheek. Old Ben was the chairman of the Kororareka Vigilance Committee and was accustomed to smell powder.’

Of all the recorded duels in the Bay of Islands and Auckland, only one, which took place in the late 1840s, seems to have resulted in death. The background to this particular affair of honour was unusual. The story goes that in the course of a discussion over after-dinner drinks in the mess of the Auckland garrison, two officers – both Scots – quarrelled. It is said that one taunted the other with being a ‘ranker’, that is an officer who had gained the Queen’s commission by rising from the ranks. This was no small matter. The great majority of officers in the British army at that time gained their commission through purchase, a practice that was supposed to ensure that the gentlemanly character of the officer corps was preserved. We know, nevertheless, that in practice some rankers became superb officers. A reforming Liberal Secretary of War, Edward Cardwell, ended the buying of commissions in 1871, in spite of the ferocious opposition of the House of Lords.

Back to the quarrel in the officers’ mess of the Auckland barracks. Here is what the author of the 1895 article wrote:

The Scottish blood of ‘the ranker’ was up in an instant and he called out the ‘purchase’ man. It is said that the affair came off near the Bastion [today’s Bastion Point], but the upshot of the business was that the aggressor [the purchase man] subsequently died, it is alleged, of his wounds. A good deal of mystery surrounded the affair, and it [the fact that there had been a duel] never got into the papers. It was given out that ‘the deceased officer strained himself jumping over a mess table’, while his lichen-covered tombstone (with a hand grenade sculptured on it) in the Symonds-street Cemetery bears an inscription that he ‘died of fever’, and that it was erected by his fellow officers as a mark of esteem.

The extent to which authorities of the time succeeded in concealing both the name of the departed duellist and the true cause of his death is shown, perhaps, by two unusual circumstances: there is no death certificate recorded for the officer; nor was there a coroner’s inquest. Even a half-century later, our 1895 reporter, who obviously knew the names of both the dead officer and his opponent, chose to maintain the early cover of anonymity.

But what of the tombstone mentioned in the reporter’s account? Unfortunately it no longer exists. During the construction in the mid-twentieth century of the approaches of the new southern motorway where it led to the city, the engineers appropriated a substantial section of the old colonists’ cemetery in Grafton Gully. By 1969, roadworks covered the site of over 4000 graves. Very few of the tombstones survived and that of the dead officer is not among them.

Yet all is not lost. Two verifiable facts remain to help establish the identity of the two duellists. The first is that only one garrison officer is recorded as having died in the township of Auckland in the 1840s, and the other firm fact – mentioned in the 1895 article – is that at least one of the two quarrelling men was a Scot. Equipped with this information, we are able to consult the database records for the Symonds Street Cemetery at the Auckland Central City Library. The Sexton’s list there tells us that the sole garrison officer to be buried in the Anglican section of the old colonists’ cemetery was one Lieutenant Alexander McLeod Hay, who died on 18 September 1848 and was buried two days later by the vicar of St Paul’s. Fortunately the library also has copies of the wording of the missing tombstones. The engravings were transcribed in 1969 as a heritage record shortly before those tombstones were removed to make way for the motorway. The recorded wording of what was graven on McLeod’s tombstone tallies with that given in the 1895 article.

Having fixed the date of death, it becomes a simple matter to move to a contemporary newspaper, the New-Zealander, which carried the following death notice two days after the burial.

On Monday, the 18th instant, after a short but painful illness, in the 30th year of his age, Lieutenant A. McLeod Hay, of the 58th Regt., eldest son of the late Colonel Hay, of Westerton, Morayshire, N [orth] B [ritain]. This officer served with his regiment during the operations in the North and South of New Zealand, and died universally lamented by his brother officers.

Hay was clearly a Scot. His unnamed ranker opponent, whose ‘Scottish blood’, we are told in the Herald article, ‘was up in an instant’ was obviously one, too. Provincial history records in the Auckland Central Library point to the other duellist as having been Lieutenant William Moir, the regiment’s quartermaster, a ranker who had been awarded his commission the year before. The New Zealand Military Journal, 1912 records that Moir fought a duel in the 1840s while he was in the 58th (Rutlandshire) Regiment of Foot, from which he retired as a half-pay officer in 1858, the year that the regiment was withdrawn from New Zealand. Another notable feature of the 1848 death notice in the New-Zealander is the evasive wording of the cause of death. Its reference to ‘a short but painful illness’, makes it remarkably similar in tone to the 1845 newspaper item dealing with the suicide of Dudley Sinclair, which blandly remarked, without any explanation, that he ‘died very suddenly’. Indeed he did. Fortunately, in the case of the Hay, sufficient evidence has survived to thwart nineteenth-century reticence and twentieth-century destruction of heritage sites.

The complete secrecy surrounding this duel is understandable. Officers in the regiments stationed in early Auckland, as other episodes in this book will attest, were anxious to conceal their personal affairs from the scrutiny of settlers, most of whom they considered socially a cut below themselves. One can only assume, moreover, that the influential surgeon of the 58th Regiment, Dr A. S. Thomson, who later wrote the first history of New Zealand and was a stickler for propriety, played some part in the cover-up. However, probably the most likely explanation of why this affair of honour was concealed is simply that, under new Articles of War gazetted in 1844, duelling became a serious military offence in the British Army. There was every incentive, therefore, for local officers to try to keep this episode in the dark, especially to conceal it from authorities at Home.

The two most famous and certainly most exhaustively recorded affairs of honour in Auckland occurred in 1842. Oddly enough these achieved notoriety because not a single shot was fired in anger. They grew out of the estrangement in Auckland between the main settler faction and the government-official-cum-military establishment. The resulting quarrels had all the confusion and rodomontade of comic opera. Offended parties challenged, and those who refused the call-out were posted as ‘blackguards and cowards’. Yet the duels were abortive: there was no spilling of blood. Such goings-on made the infant capital the laughing stock of incredulous, though secretly delighted, settlers in the Cook Strait settlements.

To understand how these confrontations came about, more must be said about the Crown colony system of government that operated in New Zealand between 1840 and 1852. Under the charter of 1840 the British government authorised the governor to set up a Legislative Council with full power to enact laws and ordinances. The council had a membership of three senior officials, and of three settlers who, because they held no public office, were popularly though misleadingly referred to as independent members. The reality was, as A. H. McLintock pointed out many years ago in his Crown Colony Government in New Zealand, they were anything but independent. In practice the will of the governor in council was supreme because ‘he could invariably count on the support of the three permanent officials’ and in the event of a deadlock ‘had the right of exercising a casting vote’. And since there was no representative assembly where settlers could obstruct official policy, the governor, provided that he kept faith with the general intent of instructions sent from the Colonial Office in London, was to all intents and purposes an absolute ruler. As early as 1842 this arbitrary rule of the governor and his officers, no less than their social pretensions, had alienated the settler community in Auckland.

‘Auckland, 1844.’ Lithograph based on a sketch of J. Adam, published by W. J. Weir, Victoria St West, Auckland. AUTHOR’S PRIVATE COLLECTION.

One does not look at the record of debates in the Legislative Council to find out why influential Auckland settlers had become so irreconcilably opposed to government policy. If the three non-official members – ostensibly representing the viewpoint of settlers from Auckland and southern settlements – were obstructive or asked awkward questions the governor could, and did, revoke their appointment. So much for their ‘independence’. This ineffectuality of dissent in the council explains why, when opposition groups formed themselves in Auckland and Wellington, they made the press their engine of complaint.

The opposition group in Auckland was not an organised party but an unstructured collection of malcontents. It had three main elements: well-to-do settlers (mainly merchants and land speculators), old land claimants who had bought land from Maori before 1840 but had not yet had their titles approved by the Crown Land Commissioners, and the hangers-on of these two groups. Calling themselves with mock-solemnity ‘the Senate’, these people met informally at hotels, usually the Exchange, or at the warehouse of the merchant firm of Brown & Campbell. What gave this disparate group its coherence was a shared detestation of Hobson’s land policies. The Senate considered that, for far too long, the colony had been held back by the shortage of cheap land, the governor’s failure to recognise speedily old land claims, and the Crown land policy of pre-emption, which prevented Maori from selling their land directly to Europeans.

The Senate’s impatience was converted into fury when, early in 1842, the newly arrived Attorney-General, William Swainson, introduced into the Legislative Council a Land Claims Bill, modelled to some extent on an earlier enactment of Governor George Gipps of New South Wales. Swainson’s measure cut back severely the land claims of those who maintained that, before the Treaty of Waitangi had introduced Crown pre-emption, they had made legitimate purchases from Maori sellers. Many of these so-called ‘old land claimants’, in Swainson’s opinion, ‘had nothing to show but the ornamental scrawl or signature of one or more New Zealand chiefs to a deed, which in its terms and phraseology, must have been utterly unintelligible to those who signed it’.

Previous criticism of Hobson had taken the form of holding protest meetings or of memorialising the governor, but now the Senate attacked him and his officials through newspapers, which quickly proved to be an effective weapon. Hobson, a former naval captain accustomed to the instant obedience of the quarterdeck, was shattered by the fractiousness of settlers who badgered him mercilessly in the local press. A nineteenth-century historian has written that once it was discovered that ‘like most officers of the Royal Navy, Captain Hobson was keenly alive to newspaper criticism … he never had a day’s peace. Newspapers unknown beyond the place where they were printed kept him in a perpetual fever.’

Shortly before the Land Claims Bill was introduced, a spokesman of the Senate, Dr S. M. D. Martin, an endlessly combative and disputatious Scot, became editor of Auckland’s first newspaper, the New Zealand Herald and Auckland Gazette. The Herald so tormented Hobson and his Colonial Secretary Willoughby Shortland that government officials took steps first to have Martin sacked as editor and then, when criticism persisted, to have the paper closed down completely.

But we are concerned not with the editorials and articles, galling though they must have been to the inhabitants of Government House and Official Bay, but the sequence of stillborn duels they provoked, duels that must strike the modern reader as all the more ridiculous because of the passion and pomposity shown by the would-be duellists. None was more so than the affair of honour between Captain Abel Dottin William Best of the 80th Regiment and William Eppes Cormack, watchmaker of Shortland Crescent and a member of the Senate.

Lieutenant Willoughby Shortland, RN. (1804–69) who, as Colonial Secretary, and later, on Hobson’s death, as Acting-Governor, became the bête noire of the well-to-do Auckland settlers. AUCKLAND CITY LIBRARIES, NEG. A11742.

The Gilbertian series of challenges began in this way. In February 1842, an anonymous article appeared in the Herald that was scathingly critical of the operation of the Legislative Council. The Official group found the article, which was obviously what we would call today a ‘leak’ or an ‘inside job’, particularly offensive. When they brought pressure to bear on the publisher John Moore to reveal the identity of the author, he, fearing a threat of libel, named as the source a non-official member of the Legislative Council, Wellington merchant G. B. Earp. A government official, Robert A. Fitzgerald, father-in-law of the Colonial Secretary, Willoughby Shortland, went to the publisher and extracted the manuscript from him, on the understanding that he, Fitzgerald, would keep it securely in his possession so that the printer could recover it in the event of a libel action.

When the Herald’s editor, the fiery Dr Martin, at whose house Earp lodged while the council was in session, heard that the article had been turned over to the enemy in this way, he was incensed. He wrote a letter to Fitzgerald demanding the immediate return of the manuscript ‘surreptitiously obtained from the printing office’. Fitzgerald refused to surrender the document. Martin then wrote again, repeating his demand, placing this letter in the hands of a friend and fellow Senate member, Charles Abercrombie, to deliver personally. The communication ended with the ominous remark that Abercrombie was appearing as Martin’s friend ‘to demand the satisfaction, which was due from one gentleman to another’. This locution carried the veiled threat that if the document were not handed over, Abercrombie would become converted on the spot from an emissary to a second, empowered by his principal to call out Fitzgerald to fight a duel. When Fitzgerald dilly-dallied for more than an hour without making a reply Abercrombie departed in disgust. The following day Fitzgerald had his reward. He was publicly posted as a ‘coward and a blackguard thing’.

Subsequently, an angry Fitzgerald counter-challenged both Earp and Martin individually. But they now declined to meet him on the grounds that, having turned down the original challenge, he had proved himself unworthy of that satisfaction. As Dr Martin later explained, because Mr Fitzgerald had already been ‘posted’ it was impossible for Mr Earp ‘or any gentleman to go out with Mr Fitzgerald, in accordance with the laws of honour’.

There the matter would surely have rested had not the impetuous and spirited Captain Best of the 80th Regiment, aide-de-camp to the governor and family friend of the colonial secretary, intervened. Best wrote to Abercrombie urging him to prevail on Martin and Earp to reconsider Fitzgerald’s challenge, adding that if they did not, the time had surely come to withdraw the posting of Fitzgerald.

This farrago of challenge and counter-challenge was brought to an end when the newly appointed Police Magistrate, Felton Mathew, presumably on the instructions of Governor Hobson, called at the residence of Dr Martin. There, according to the 1895 account, he obtained ‘that gentleman’s word of honour, as well as that of Mr Abercrombie, that no breach of the peace should be committed towards Mr Fitzgerald’.

But Best was not to be forgiven by the Senate clique for what they considered had been his unwarranted interference. About a month later, on St Patrick’s Day 1842 to be exact, Dr Martin called on Captain Best. He announced that he had come as the second of William Cormack, another member of the Senate, to present a verbal challenge for a duel. Best promptly accepted, nominating his friend, Edward Shortland, Hobson’s private secretary, as his second. Neither Best’s journal nor the press, which fully reported these fantastic challenges, raked over the coals to tell us what this particular disagreement was about. In fact, the only reference Best makes in his journal to the occasion is to place the laconic marginal note in brackets beside the date, ‘The day of the Fight’. However, Logan Campbell tells us in his reminiscences that it was agreed that the duel would take place in the nearby Domain, at that time very much a wilderness.

At 6 a.m. the next day, a ‘tremendously squally’ morning we are told, the four men met. Pistols were loaded, but at the last moment the seconds quarrelled over which pistols were to be used. Best had a fine pair of duelling pistols, which, Martin complained, put his man at a disadvantage. According to a statement later made by Shortland, Martin wanted a coin to be tossed to determine whether Best’s or Cormack’s pistols were to be used. Shortland said: ‘to this I objected on the ground that Mr Cormack’s pistols were short, and not regular duelling pistols as were Capt. Best’s … but, to avoid any difficulties, I agreed that Mr Cormack should have the use of one of Capt. Best’s pistols, the choice to be determined by toss’. This did not satisfy Martin who maintained the duellists would meet on an equal footing only if a coin were tossed, first to determine which brace of pistols should be used, and second to decide who would have the first choice of pistols. After a half-hour wrangle, Shortland withdrew his man in disgust. Not a shot had been fired.

Later in the morning, first Martin, then ‘Campbell the auctioneer’ (Dr John Logan Campbell of the Senate) approached Edward Shortland bearing a letter wishing to ‘reopen the matter’. Shortland refused, however, saying that ‘Captain Best having once been made a fool of, I decline placing him again in the same position’. After this rebuff to their demand, Cormack and Martin placarded Best and his second Shortland as cowards in the public places of Auckland.

As a typical officer of the Regular Army in Auckland, Best cared little about how he was regarded by local citizenry. But he cherished the regard of his fellow officers and was angered by the imputed stain on the good name of his regiment and that of the garrison. As acting officer commanding the garrison in Auckland during the temporary absence of Major Thomas Bunbury, Best summoned garrison officers to a meeting where he and Shortland gave their version of the circumstances behind the abortive duel. Senior officers of the three regiments – the 80th, 96th and 28th – then stationed in Auckland thereupon signed the following formal declaration:

The assembled officers having examined Captain Best’s pistols, are unanimously of opinion that they are correct duelling pistols, and, from the statement of the facts laid before them they entirely approve of the line of conduct adopted by Captain Best and Mr Edward Shortland, and are further of opinion that Captain Best and Mr Edward Shortland should take no notice of any placards or observations arising out of the transaction.

And they didn’t.

But once heated, Martin stayed on the boil. The rebuff rankled. He wrote a letter to Sir Maurice O’Connell, commander of the military forces in New South Wales, complaining of the conduct of his officers garrisoned in Auckland, ‘inasmuch as they, contrary to the Army Regulations, interfered in the quarrels of civilians’. He went on to denounce Best as ‘a coward’. The letter concluded sourly: ‘It is apparent that the officers of the garrison, however anxious to interfere with civilians, have manifested an extraordinary degree of reluctance in giving proper satisfaction’.

Best, however, carried on serenely, seemingly unflustered by the episode. He probably knew in his heart that he was no coward. Nor could any person today who reads his delightful Journal of Ensign Best believe him to have been one. And certainly, says Nancy Taylor, he showed bravery on the day of his ‘harsh death’ at the age of 29, in December 1845, killed while gallantly rallying his ambushed regiment at Ferozeshah, India, during the Sikh War.

The most famous affair of honour in early New Zealand, though taking place outside the Auckland province, warrants mention in this account. It was fought out on the Te Aro Flat in Wellington in 1847 between Dr I. E. Featherston, editor of the Wellington Independent, and Colonel William Wakefield, chief agent of the New Zealand Company. Wakefield called out the doctor for writing an editorial in which he implied that the colonel had acted on behalf of his company in a way that made him virtually a thief. The story goes that Featherston shot first and missed, whereupon Wakefield ‘fired in the air with the comment that he would not shoot a man who had seven daughters’. Philip Temple, biographer of the Wakefield family, has pointed out obvious inconsistencies in this tale, a tale he speaks of as having ‘grown in the telling’. For instance, Featherston had then fathered only three daughters. But there is no doubt that this duel did indeed take place, for it caused a great stir throughout the whole colony.