When Captain Hobson travelled in HMS Herald to New Zealand as first governor he brought with him a number of officials he had recruited in Sydney. Perhaps he was unaware that he had also brought over from New South Wales a hidden cultural cargo, the tradition of conflict between press and government. For many years, settlers in New South Wales, lacking effective representative institutions, had used the printing press to protest against the policies of their governors. In retaliation, governors had passed laws that regulated the conditions under which newspapers were published, and rigorously defined the law of libel. These laws they applied harshly.

Antagonism between press and government quickly resurfaced in New Zealand, particularly in the capital of the colony. Because Auckland remained the centre of government for 25 years, it had a high proportion of the colony’s early newspapers. G. M. Meiklejohn who, in 1953, made a special study of early Auckland newspapers, wrote that out of the nine papers published in New Zealand by the end of 1842, ‘seven [were] in the northern settlements of Kororareka and Auckland’. He went on to observe that ‘no less than 30 journals which could legitimately be regarded as newspapers were published in Auckland and its immediate environs between 1841 and 1871’. Of these 30 newspapers easily the most bizarre was the Auckland Times published by Henry Falwasser between 1842 and 1846.

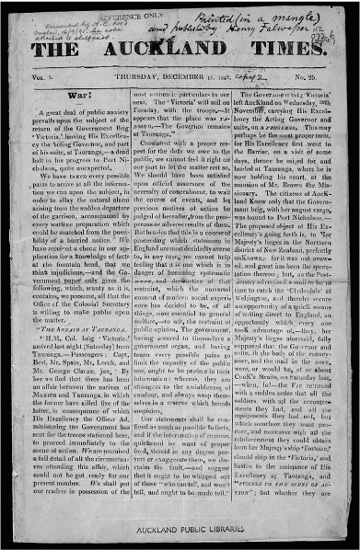

An edition of the Auckland Times of December 1842. For more than a year, Henry Falwasser was forced to use any type he could lay his hands on in order to bring out the newspaper, which he printed on a household mangle. AUCKLAND CITY LIBRARIES, AUCKTIMES.15.12.1842PG1

Not much is known about the antecedents of Falwasser before he became self-appointed champion of free speech in early Auckland. There is evidence that at one stage he was a merchant and storekeeper in Sydney. And we know that his sister Mary, who preceded him to New Zealand, married the Rev. John F. Churton, vicar of St Paul’s, Auckland’s first church. Apart from his commercial activities during his Australian existence, Falwasser seems to have had some experience in printing and publishing. He later claimed that he arrived in Auckland and settled in upper Shortland Crescent with the express intention of taking up a position on Auckland’s first newspaper, the New Zealand Herald and Auckland Gazette. To understand why Falwasser decided to change course and to found the Times more must be said about its forerunner, usually just called the Herald.

In mid-1841, 20 subscribers, half of them officials, the other half merchants and local capitalists, formed the Auckland Newspaper and General Printing Company. Once incorporated, the company set up printing works equipped with good machinery and a wide variety of types acquired from Sydney. The founders of the company placed the management of their new concern in the hands of an experienced Irish printer, John Moore, said to have been brought over from Tasmania by the authorities in 1840 to be their first government printer. On 10 July 1841, the company published the first issue of the New Zealand Herald and Auckland Gazette at the cost of a shilling a copy.

At first, the success of the venture seemed assured. Not only did the company have the backing of the official establishment. It also had a guaranteed income that would inevitably arise from printing government regulations and public notices.

But according to Dr T. M. Hocken, the authority on the colony’s early newspapers, the Herald’s career was ‘short and stormy’. In spite of its potential profitability, it was bedevilled from the beginning by the opposing courses plotted by the two groups of trustees contending for the control of the paper’s policy. Those drawn from the ranks of the officials looked on it as the mouthpiece of the administration. Trustees representing the well-heeled settlers of the township, who had also been recruited to serve on the board, thought otherwise. They believed that the editor should be free to use the Herald to attack the government’s land policy which was then virtually the be-all and end-all of Auckland politics.

Antagonism intensified late in 1841, when Dr S. M. D. Martin, a prominent leader of the Senate, took over the editor’s chair of the Herald. Martin was a fiery Scot with a taste for invective. And embedded in this temperamental combativeness was a self-regarding element arising from his questionable claim, as yet uninvestigated by the Land Commissioners, over an extensive area of land in the Thames Valley which he professed to have ‘purchased’ from Maori owners before the signing of the Treaty of Waitangi. In the early weeks of 1842 matters came to a head. Martin began using the paper to savage Hobson and his new Attorney-General, William Swainson, whose new Land Claims Bill was designed to forestall Pakeha land-sharking.

So enraged were Hobson and his officials by Martin’s attacks that, working through the majority vote of the trustees they had appointed to the parent company, they successfully contrived to shut down the Herald and its associated printing press. Later in the same month, the Colonial Secretary, Willoughby Shortland, acting on behalf of the governor, bought up the printing plant and type of the company as a job lot before the liquidator could put them up for public auction. Shortland had hatched an artful plan. He intended to set up a government printing establishment, to which the settler opposition would have no access. Further, the officials, using the printing press now in their hands, were able to create a puppet newspaper, edited by Swainson, which they called the Auckland Standard. But this rather boring publication expired before the year was out.

When the Herald folded, a void opened up which an effective opposition press could now fill. Falwasser’s hour had come. He stepped in and founded the Auckland Times. At first he did not set out to provoke. He claimed that by steering clear of politics he would survive where his predecessors had come to grief. Nor could Falwasser have been unmindful of the fact that since his printer, John Moore, was using government-owned type to print his new paper, there was every incentive to be politically circumspect. Falwasser’s aim, so an early issue proclaimed, was to provide ‘an able, honest and independent Press … untrammelled by any party, uncontrolled by any subserviency’, and this would enable him to ‘exercise the irrepressible POWER OF TRUTH for the common weal’. ‘Dissensions in our infant community’, he editorialised piously, ‘can only hinder our progress.’

The first numbers of the Times were not particularly exciting. Falwasser turned out orotund Micawberish editorials in which he would sometimes give vent to a number of his many private fads and crotchets. He maintained, for instance, that Auckland would become a real town only when it gave up building in timber and weatherboard and started to use brick. (Falwasser’s rival, Dr Martin, dismissed him as ‘crack-brained’.) Falwasser also provided a solid diet of local gossip, arguing that this would make a particular appeal in ‘a young and closely packed community like ours’ where rumour abounded. Even so, over half of the copy of the early issues of the Times was made up of scissors-and-paste cuttings from other colonial papers. All rather innocuous, one would have imagined.

But though Falwasser aimed at political neutrality, he was not neutral enough, it seems, for officialdom. Following the death of Hobson on 10 September 1842, Willoughby Shortland, who became acting governor, stepped in and forbade Moore to print the Times any longer. William Chisholm Wilson, who in 1863 founded today’s New Zealand Herald, could remember the day that Falwasser was threatened with deportation for daring to criticise the government.

Thus threatened by a revived government monopoly of news, the Times underwent a sea change. Almost overnight it mutated from a nondescript local paper into what Dr Hocken later described as ‘the most extraordinary paper ever printed’ in New Zealand. Confronted by government intransigence, Falwasser proved himself to be ‘a man of ingenuity and resource. From any quarter he gathered a miscellaneous assortment of old type, such as is used for printing bill-heads and rough jobs, and with the aid of a [household] mangle and coarse paper, triumphantly produced these weekly specimens now regarded as such a curiosity.’

In his leader for the issue of 28 October 1842, which progressively displayed a whole miscellany of fonts – the leftovers of the infant printing industry of Auckland – Falwasser made his case. It was ‘the puerile, inconsiderate, contemptible attempt to stifle the expression of public opinion’, he wrote, ‘which has driven us to the MANGLE.’ The following imprint at the foot of the last page was displayed almost as a badge of honour:

AUCKLAND

Printed (IN A MANGLE) and Published by

HENRY FALWASSER

Sole Editor and Proprietor

In his struggle to get his issues out Falwasser demonstrated great typographical ingenuity. As a result, numbers for the later half of 1842 often presented a curious patchwork appearance. As one set of type was used up in the current issue, Falwasser would begin to work his way through his assortment of fonts: Canon, Baskerville, Non-pareil, Brevier, Gothic and so on.

In those days of typographical famine, one letter in particular was in very short supply: the lower-case ‘k’. So Falwasser resorted to using anything that was on offer – capitals (no problem here: he was much given to capitals, anyway), Gothic, even German text. And when he reached the later part of the issue and could not lay hands on a ‘k’ of any kind whatsoever, he left a gap. The effect was hilarious.

Getting hold of type was not Falwasser’s only publishing problem. Newsprint was equally scarce. Occasionally he had to make do with rough wrapping paper, and a coarse spongy paper that absorbed printer’s ink, just like a blotter. This made adjusting the compression to be applied to the rollers of the household mangle a tricky business. Some numbers had the ink driven through to the reverse side of the paper. For these issues Falwasser improvised by printing on one side of the sheet only.

Yet he was prepared to laugh at his own efforts, for Falwasser was not a pompous man. And he was sustained in his efforts by the conviction that he was enabled by his ‘ponderous revolver’ – as he once referred to his mangle – ‘to strike a blow at would-be despotism. … We consider our mangle an ingenious and honourable triumph over as contemptible and sneaking an attempt to stifle the press as was ever perpetrated.’

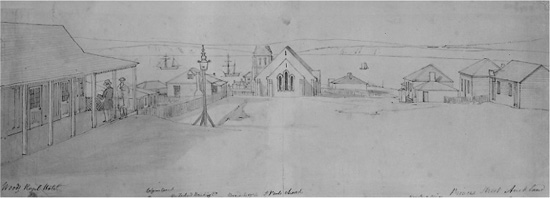

‘Princes Street, Auckland.’ A sketch in pen and wash by Edward Ashworth, 1843? It was in Wood’s Royal Hotel, shown on the near left, that Falwasser and Lt Phillpotts had their quarrel that led to a duel on the adjoining section. AUCKLAND ART GALLERY TOI O TAMAKI.

By the beginning of 1843 the Times was able to cast aside its previous tatterdemallion appearance. New type obtained from Sydney and, somewhat later, supplies of better paper, gave the newspaper a respectable aspect. The following year he was able to dispense with the mangle. The imprint now read that the paper was ‘Printed and Published by Henry Falwasser (sole editor and proprietor) at the Times Office, Shortland Crescent’. And, whereas in earlier times the paper had been distributed gratis, subscribers were now expected to pay 10 shillings a quarter.

Not everyone had a high opinion of the Times. One such was that local character, the monocle-wearing Lieutenant George Phillpotts, second in command of the sloop HMS Hazard. Though the son of the bishop of Exeter, he was well known for his outspoken views expressed in lurid language. The story has been told that, in late 1844 or in early 1845, Phillpotts was reading an issue of the paper in S. A. (‘Rakau’) Wood’s Royal Hotel in Princes Street just opposite Government House. According to the article on duelling in an 1895 issue of New Zealand Herald, ‘Something in the columns [of the Times] displeased … the gallant lieutenant … and he denounced it as “a rag”, and proceeded to dilate upon the various uses to which it could be put, which so incensed Falwasser that he called Phillpotts out.’ Shots were exchanged on the vacant section which then adjoined Wood’s hotel, but is now part of the site of the prestigious Northern Club. But nothing worse happened than Phillpotts losing a button off his uniform, and Falwasser getting a bullet through his coat-tail. Since the quarrel was taken no further, we can only assume that the honour of both parties was satisfied.

Governor Robert FitzRoy, 1805–65, whose well-intentioned but ill-considered financial and Maori policies, which were supported by Falwasser in the Auckland Times, led to his recall in 1845. AUCKLAND CITY LIBRARIES, NEG. C 28976.

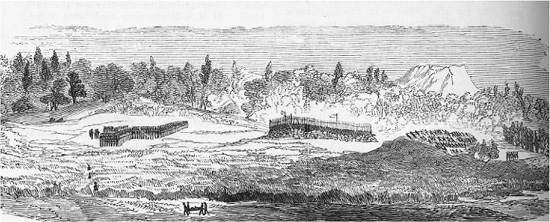

Certain features of this tale strain credulity, put it even beyond parody. But apocryphal or not, that is the story that has come down to us today. The episode demonstrated that Phillpotts, though hotheaded and truculent, was not deficient in courage. He had occasion to show the same pluck – and, regrettably, the same foolhardiness – during the Northern War, when he was killed while climbing a scaling ladder in an attempt to storm the palisades of Hone Heke’s well-defended pa at Puketutu near Ohaeawai.

What of Falwasser’s Times? Paradoxically, the period when it was printed on a mangle was to represent its glory days. These were never to return. In praising the Times as ‘continuing in its former hearty and independent style’ right up to the time of its expiry, Hocken was surely being too generous. During 1844, in spite of its new typographical garb, the paper began to go downhill.

Two factors were at work here. First, Falwasser no longer had the field to himself. In April 1843, Brown & Campbell’s newspaper, the Southern Cross, began publication. Two years later the Times had another competitor on its hands, the New-Zealander, founded by John Williamson and W. C. Wilson in June 1845. Both these new weeklies were professionally run, technically proficient and presented journalism of a high standard. In contrast, the Times seemed amateurish in format and grew increasingly pedestrian in content.

‘The attack on Heke’s pa at Okaihau; from a sketch by one of the officers.’ The brave if impetuous Lt George Phillpotts was killed during this failed attack on Puketutu pa. R. A. A. SHERRIN & J. H. WALLACE, EARLY HISTORY OF NEW ZEALAND, AUCKLAND, 1890, P. 706.

But even more damaging to the Times was the self-inflicted blow of an about-turn in editorial policy. Shortly after the arrival in December 1843 of the new governor, Captain Robert FitzRoy, Falwasser moved from a position of opposition to the governor to one of full support for the new administration. He acted as a cheerleader, for instance, for FitzRoy’s new departure in ending Crown pre-emption in the purchase of Maori lands. Time quickly showed that this policy of the new governor was ill conceived. But more importantly for the future of Falwasser’s paper, by advocating ‘Free Trade in Land’ he made the Times largely indistinguishable from the Southern Cross, the avowed mouthpiece of the Auckland land speculators. Not surprisingly, many former readers switched their allegiance to the Cross.

But a falling circulation did not bring about demise of the Times. It struggled on until 17 January 1846. A week later Falwasser died. It is somehow fitting that the Mangle newspaper, and its spirited proprietor and pioneer advocate of the freedom of the press, should have quit the Auckland scene together.