On Sunday morning at eight o’clock, ‘all hands on deck to witness the punishment’ was piped on board HMS Rosario, and a couple of her men received three dozen each at the gangway. We are not aware of the nature of the offences, but they must have been of a very serious nature, as flogging in port is extremely unusual. – New Zealand Herald, 24 June 1872

The armed services, especially the military, were a most emphatic presence in early Auckland. Dr Arthur Thomson, surgeon of the 58th Regiment, wrote that Wellington settlers generally believed that only the expenditure of the military and its commissariat kept Auckland financially afloat during the 1840s. This economic impact had a private dimension as well. Army officers, most of whom had purchased their regimental commissions, were usually well connected socially in the old country. And as a general rule they were also well off – early deeds of mortgage in the Land Registry often list army officers as lending money to local settlers on three-year terms at the then going annual rates of interest of 15 per cent or more.

Army and naval officers, together with the governor’s senior officials, were the core of the capital’s social elite: they were essential guests at the governor’s balls and levees. And they marshalled their forces, especially the highly popular regimental band, to provide pageantry and spectacle for public occasions like the annual Queen’s Birthday commemoration – the social event of the year – or special one-off celebrations such as that held on the signing of the Treaty of Paris in 1856, which formally concluded the Crimean War. P. S. Best, historian of the 58th Regiment, known as the Black Cuffs because of the black facings on their uniform, tells us how the regiment delighted the large crowd on that occasion ‘as it went through the trooping of the colours and various parade ground manoeuvres accompanied by the Regimental Band’.

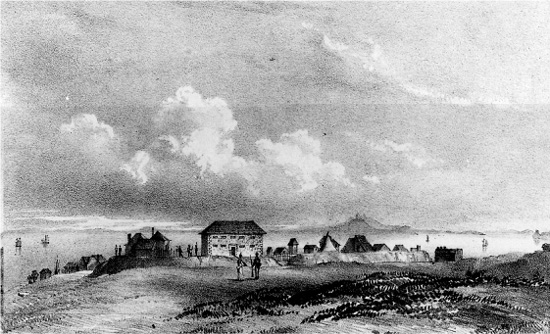

Fort Britomart and the Barracks viewed from the foot of Princes Street, late 1841(?); drawn on stone by P. Gauci after J. J. Merrett. This lithograph appears in Charles Terry, New Zealand, Its Advantages and Prospects as a British Colony, London, 1842.

Even in the years between the destruction by fire of the first government house in 1848 and the opening of the second in 1856, the band performed on the vacant grounds of the house. ‘Once a week during the summer,’ wrote William Swainson in 1853, ‘a regimental band plays for a couple of hours on the well-kept lawn in the government grounds; and with the lovers of music, and those who are fond of “seeing and being seen”, “the band” is a favourite lounge.’ The band by no means limited itself to playing marches. Its varied repertoire also included dances ranging from waltzes to polkas and schottisches, and overtures selected from the popular Victorian operas of Auber, Flotow, Rossini and Weber.

The armed services were members of Auckland’s first dramatic and musical groups, as well. And they were to the fore in sporting activities. The army had its own cricket club, and officers helped to organise the settlement’s first race meeting held on 5–6 January 1842 at Epsom, providing then and at later meetings a quota of gentlemen riders.

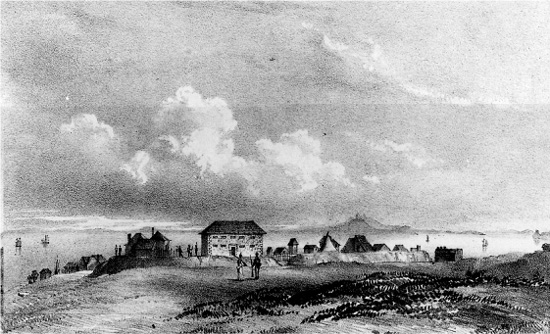

East-central Auckland, 1852. An undated retrospective sketch which labels the landmarks in Hogan’s 1852 drawing. Particularly notable are the extent of the Albert Barracks and the way that Wakefield Street acted as a main access route to and from the town. OLD NZ PRINT NO. 272, AUCKLAND CITY LIBRARIES.

During the 1840s, the New Zealand Government Gazette and the capital’s first newspapers constantly referred to army and navy activities in the settlement. The Gazette, for instance, periodically published the names and personal details of soldiers who had deserted. The deserters were usually young – about 24 years of age – often Irish; some were described as bearing on their bodies the mark of ‘corporeal punishment received in New Zealand’. Army discipline could be extraordinarily harsh. In the early 1850s, one officer notorious for meting out severe punishment was nicknamed ‘Triangles’, after the triangle at the fort where miscreant soldiers were tied to receive the lash.

For their part, the early newspapers seemed to have regarded military and naval activities as good copy: articles on the construction work carried out by soldiers in the settlement appeared frequently in the press. Indeed, the military could be regarded as pioneer road builders of early Auckland. Take this typical press item taken from the New-Zealander. ‘On Monday 25 September [1848] one hundred men of the 58th regiment were placed to work upon the track [to] the crown of Cemetery hill’, more or less where the western entrance to the Grafton Bridge now stands, along ‘the line which runs from the Albert Barracks’. This clay track, today’s Symonds Street, had been specially cut in September 1842 to the allow the passage of the funeral cortege of Governor Hobson to the new colonial cemetery. It must be remembered that during Auckland’s first two decades Wakefield Street was the highway out of that part of town: some early maps label it the ‘Queen Street Extension’. The more convenient link with Epsom and the outlying settlements like Onehunga, however, was the Parnell Rise and Manukau Road.

Periodically the press also praised the work of the soldiers as guardians of law and order in the settlement and guarantors of safety. They were always on call to deal with the threat of riot or any other public calamity. They often acted as an auxiliary police force guarding prisoners in gaol, or maintaining order at race meetings. In July 1858 soldiers from the barracks were called out to help the volunteer fire brigade when a fire, which broke out in the Osprey Inn in High Street, threatened to engulf the whole of central Auckland. Fortunately, a change of wind and accompanying rain brought success to the combined efforts of these two groups. But the role of the soldiers was not forgotten.

Not surprisingly, therefore, service matters are central to the story of Auckland during its years as capital. Servicemen were associated with the very beginnings of settlement. In fact soldiers were stationed in Auckland months before Governor Hobson himself went to live there and in that sense provided Auckland with its first official British settlers. In November 1840, a detachment of 50 men of the 80th Regiment, who had come south from the Bay of Islands, immediately set about constructing, out of volcanic rock and brick – they built their own brickyard close by – the fort and barracks on the promontory known as Point Britomart. The town’s fortress complex, which must include the barracks later constructed more or less where Albert Park is today, was for years the most substantial set of public or private buildings in the early town. Over a period of years following the Northern War, George Graham, clerk of works of the Board of Ordnance, supervised Maori masons who built a stone wall 15 to 20 feet high, loopholed and with flanking angles, enclosing 21 acres. This enclosure, designed to be large enough to provide a place of refuge in the event of hostilities, also contained soldiers’ quarters, a military hospital, magazine and stores, for the most part once again built by Maori workmen.

Furthermore, because Auckland continued as capital until 1865, the bulk of the armed forces in the colony – estimated at around 2000 by the later 1840s – were stationed here to be at the disposal of the governor and his advisers. Nor should it be forgotten that the 1845 armed uprising of Nga Puhi warriors under Hone Heke and Kawiti led to a marked increase in the number of soldiers based in Auckland. That war, by alerting settlers to the further threat, real or imagined, of a future Maori invasion from the south, presumably by Waikato iwi, led directly to a further addition to the military component of the population. Between 1847 and 1852, the four Fencible settlements were established at Howick, Otahuhu, Panmure and Onehunga, as bastions guarding the southern approaches to the capital. Some 700 imperial army veterans, most accompanied by wives and families, were settled under this scheme. It has been estimated that by 1851, serving soldiers, Fencibles and their families made up just on 30 per cent of Auckland’s population.

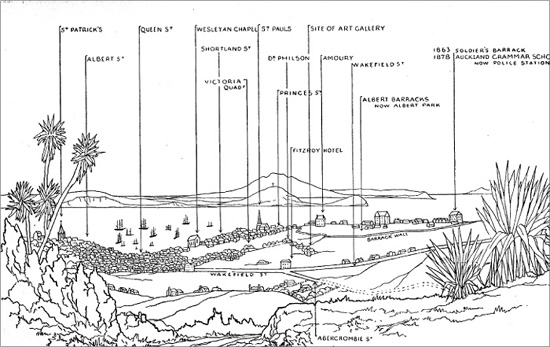

Fort Britomart. A plan of the inner city, drawn in 1937, which shows the position of old Fort Britomart in relation to the street system and wharves by that later date. AUCKLAND CITY LIBRARIES, NEG. 1287.

Nor were the Fencibles the only ex-servicemen to settle permanently in the region. When, in 1858, after thirteen years’ service in the colony, the 58th Rutlandshire Regiment finally departed for ‘Home’, a large number opted to take their discharge here. P. S. Best records that of the 350 rank and file of the 58th serving in Auckland at the time of withdrawal, only 120 embarked on the troopship Mary Anne when she finally left on 19 November. That they should have been allowed to stay was not exceptional. In years gone by many had already been demobbed here. Indeed, it was the existing imperial policy to carry out what was known as military colonisation, that is to encourage experienced soldiers to settle in colonies after the departure of their corps as a potential reserve force. Over the years a substantial number of the 1400 men who had served in the colony under the colours of the 58th Regiment stayed on as settlers.

Fencible cottage, Panmure, 1940s photograph. The attic story indicates that this is a sergeant’s house. The skillion and roofed verandah would probably have been nineteenth-century additions, while the outhouse beyond the skillion almost certainly would have been of twentieth-century construction. AUCKLAND CITY LIBRARIES, NEG. 42575.

A number of the soldiers who stayed are reputed to have taken Maori brides, a practice which, according to Thomson, had official approval, presumably to implement integration. Robert Hattaway, a one-time coloursergeant in the regiment, who came with the first detachment in 1845 and himself retired to become an Auckland settler in 1856, believed that perhaps as many as 1100 time-expired men from this unit were ‘absorbed by the colony’. Thomas Gore Browne, who was governor from September 1855 to October 1861, once observed that members of the 58th made up one-eighth of Auckland’s population. As many of these ex-soldiers had a background of farming or of skilled trades such as carpentry, masonry and baking, they were well equipped to become useful settlers.

Not all the military who elected to remain were rank and file. Some medical officers like assistant surgeon T. M. Philson and J. H. Hooper resigned from the army to practise in Auckland, in Philson’s case famously so. When the 58th returned to England, Captain H. C. Balneavis, who had originally come out in charge of the light company of the regiment to take part in Heke’s war, did not go back. Like Major Henry Matson, and a number of officers from the capital’s regiments, he retired from the army and settled in Auckland. A fine violinist and musician, Balneavis was one the founders of the Auckland Choral Society.

The military character of Auckland became even more marked in the 1860s with the heightening of racial tension in the North Island. When, in 1863, war broke out against the Maori King and his supporters in the Waikato, and in the western Bay of Plenty, military and naval forces became so concentrated in Auckland that the city and its environs temporarily took on the colour of a huge armed camp. The end of the Waikato campaign and the shift of military operations to other parts of the North Island caused a marked decline in the number of servicemen in Auckland. But more significant in the long run in bringing about this dilution of the military component in the population was the decision taken by the home government in the 1860s progressively to withdraw its regular troops from the colony. Imperial thinking was that once a settlement colony such as New Zealand had acquired responsible self-government, it must be ‘self-reliant’ and face up to the military consequences of its own racial policies. In 1865 the first imperial regiment sailed away. In February 1870 the process was complete when the last detachment of British troops left. The days of Auckland as a garrison settlement were then at an end.

What is known about those first three decades when regular units of the Royal Navy and the British Army were so visible a feature of Auckland life? A certain amount of information has been faithfully recorded in our history books, particularly when they deal with the times of war between Maori and Pakeha. But the detachments of the armed forces stationed in and around Auckland have almost invariably been depicted as collective entities, whose function in the story of the colony has been to act as upholders of the Queen’s peace or, to put things more bluntly, to act as the agents of British colonisation. What the individual soldiers and sailors thought, or felt, about the role they were called on to play has rarely reached the printed page in fact or fiction. New Zealand literature has no immortal trio like Rudyard Kipling’s Privates Mulvaney, Ortheris and Learoyd. It’s almost as though our redcoats and bluejackets have been kept in the shadows. Nobody has been at hand in New Zealand to characterise them honestly but sympathetically, as Kipling later depicted British rank-and-file soldiers in India: ‘We aren’t no thin red ’eroes, nor we aren’t no blackguards, too’.

Who were these servicemen? Thayer Fairburn, in his book on the shipwreck of the Orpheus, shed a revealing light on the Royal Navy bluejackets of the 1850s and 1860s serving in New Zealand by making a point of exploring the origins of every sailor who drowned. He found that the seamen came not only, as one would have expected, from traditional naval towns such as Portsmouth and Chatham, and the vicinity of large ports such as London, Bristol and Hull, but also from inland and rural districts, particularly those areas racked by poverty and unemployment. This latter phenomenon is analogous to the enlistment pattern provided by the rank and file of the army, except that, for that service, recruitment in Scotland and especially Ireland was even more marked. Obviously the most effective recruiting NCO was, so to speak, Sergeant Poverty.

Men joined the regular army, or ‘took the Queen’s shilling’ as they said in those days, in spite of hard conditions, overcrowded living quarters and discipline brutal – flogging and branding were not finally outlawed in the army until 1871. Flogging was abandoned in the Royal Navy only in 1881. Moreover, recruits could scarcely have been attracted by the prospect of army food. Daily rations during the early 1850s, for instance, were one pound of bread, three-quarters of a pound of meat and a small quantity of tea, coffee and sugar. The provisions issued to soldiers in Auckland during the early 1840s consisted of one pound of bread, one pound of salted pork – called locally ‘New Zealand venison’ – or fish (not the customary salted beef that redcoats considered more appetising), coffee in the morning and tea in the evening. Hardly living in the lap of luxury. It was stated in the House of Commons at the close of the Crimean War that the cost of keeping a convict in a new prison was greater than that allowed for the maintenance of a private soldier. In The Victorians A. N. Wilson explains that the military authorities worked on the principle that a serving soldier should be ‘marginally better off than the lowest paid agricultural worker in England’. This fact, Wilson believes, accounts for the large proportion of men enlisting from Ireland where, after the Great Famine, living conditions were appalling. All empirical evidence suggests that a background of economic hardship was common for many of the redcoats and bluejackets who ended up serving in colonial New Zealand.

Yet in spite of their generally deprived background, once these men were exposed to and impregnated with the values and traditions of their unit, they developed a surprising esprit de corps and a genuine pride in the good name of their regiment or, in the case of the Royal Navy, their arm of the service. A distinction between the two services must be made. Soldiers in the ranks tended to be loyal to the regiment to which they were permanently attached. This was in contrast to the Jack Tars, who, after a tour of duty were often shifted from their returning warship, especially if that vessel was about to pass through a period of refit or repair, which could take months, to be scattered through short-handed ships ready to sail from Britain. This explains why seamen tended to regard themselves as belonging to the Royal Navy as a whole rather than to any one particular ship.

But, regardless of which branch of the armed services they were in, loyalty to their unit, combined with a shared sense of male clannishness, provided the cement that bound these servicemen together. Hence, as we shall see, their furious response to any attempt to defame the regiment or branch of the Royal Navy to which they belonged. And because disorders in New Zealand involving servicemen and civilians were invariably reported in the press, these newspaper accounts help us to discover something of the inner thoughts of the rank and file of the services and especially how they regarded the settlers whose interests they were often called on to protect.

In his wonderfully lively book Old New Zealand, Judge F. E. Maning wrote that the early colonists completely underestimated the skill and prowess of the Maori as warriors. So at first did the British army officers. Some of them spoke of ‘marching through New Zealand with 50 men’. As a former Pakeha–Maori, Maning knew better. Even 500 redcoats, he maintained, couldn’t do that. The early months of the Northern War, which broke out in 1845, some of whose major fights he witnessed at first hand, proved his hunch to be absolutely right. The settlers believed that if confronted by a European show of force Maori would quickly fold, so the success of Hone Heke of Nga Puhi during the first weeks of the Northern War shocked them to the core. The loss of Kororareka in March 1845 was completely unexpected.

But first let us summarise the background to this particular disaster. In February 1845, Governor FitzRoy had sent from Auckland an officer and 30 men – the number was later increased – initially to re-erect the flagpole that Hone Heke had cut down as a symbol of British authority, and then to build a blockhouse close by to protect it. This task was completed while the 18-gun sloop-of-war, HMS Hazard, remained on guard in the bay.

On 11 March, Heke, aided by the skilled warrior chief, Te Ruki Kawiti, attacked the town on three fronts. Kororareka was defended by 50 soldiers from the 96th Regiment, 90 marines and sailors from the Hazard and about 110 armed settlers who are listed here as combatants in spite of their limited military usefulness. Heke’s forces captured the blockhouse with ease, and drove back in confusion both the soldiers of the 96th and the naval forces from the Hazard. Soon the Maori attackers were in possession of the whole town apart from the stockade within which the settlers and their families and a remnant of the military took shelter. An accidental explosion of the ammunition dump inside the stockade, however, led the Europeans to abandon any thought of making a rearguard stand there. Unmolested by Heke’s men, the settlers and their families were evacuated to three ships anchored in the bay: the Hazard, an American corvette named the St Louis and a large English whaler, the Matilda, which had fortuitously appeared on the scene. Gloomily, the Hazard’s marines, and troops of the 96th Regiment, watched from the harbour as the greater part of the township was sacked and burnt to the ground.

This was a humiliating defeat for the British. At least ten of the servicemen had been killed – the exact total seems to depend on which book you read – and a greater number wounded, some very seriously, including Commander David Robertson of the Hazard. Whereas the Maori strategy had been carefully planned and skilfully executed, British preparations for the defence of Kororareka had been slapdash, their officers inept and the military skills of the soldiers of the 96th, most of whom were raw recruits, inferior to those of their formidable foes.

Does this result confirm Wilson’s characterisation, perhaps intentionally overstated, of the early Victorian army as a force run by gentlemanly officers, many of whom were buffoons, leading working-class men driven by privation to take up a military calling that their heart was not in? Well, not altogether. As an eyewitness of the Kororareka engagement pointed out, the British overconfidence and lack of preparation for a testing engagement against a brave and skilful enemy arose from false racial assumptions generally held by European settlers in this age of colonisation. ‘Native courage was so undervalued as to have given rise to the belief that as soon as one or two men were killed, they [the Maori] would run away, and the war be at an end.’

This story now moves back to Auckland. On 16 March 1845 news got about the town that three large ships were signalling their approach to the Waitemata Harbour. Curious settlers impatiently awaiting mail from Home had already become adept at reading the signals from the signal station on Mount Victoria long before incoming ships had rounded North Head and entered the harbour itself. It was presumed at first that these were ships from Sydney bearing military reinforcements whose arrival was anxiously expected. When these ships proved instead to be the Hazard, the St Louis and the Matilda, filled with refugees from Kororareka, and bearing news that the colony’s first township had been destroyed, there was consternation and panic among the settlers. Did this also mean that Heke could attack Auckland, as he had earlier threatened to do?

Even the arrival from Sydney of 150 members of the 58th Regiment on HMS North Star within the next week did little to allay the people’s panic. ‘Out-settlers,’ wrote the nineteenth-century historian J. H. Wallace, ‘dreading a war of races, congregated about Auckland. Several colonists left the country, and property could be bought at a nominal price. Britomart barracks were entrenched and two blockhouses built. A militia ordinance was hastily passed, and three hundred men were trained to arms.’ A fort was built near the Catholic chapel on the west side of town, and, on the east side, St Paul’s Anglican Church, its windows hurriedly barricaded with bulletproof boards, was designated along with Fort Britomart as a refuge for women and children in the event of a Maori attack.

With hearth and home in danger Auckland settlers became very warlike, and thirsted for scapegoats for the shameful debacle of Kororareka. They found them when a few of the refugees from Kororareka began openly to complain that their town had been lost because of the cowardice of the soldiers. Admittedly the men of the 96th Regiment had not shown up well in the fighting. But in fairness it should be said that not only were they inexperienced, but they had also been badly led. Governor FitzRoy did not mince matters when he reported to his masters in England that the conduct of the officers in charge had been ‘shameful’ and ‘useless’.

On their return to Auckland, the soldiers of the 96th were embittered by their treatment at the hands of civilians who did allow them to lick their wounds in peace. Fire-eating citizens of the capital branded them cowards. For soldiers of the Queen, far from home, whose comrades had been killed and wounded in a war that seemed to them largely of the colonists’ own making, this was too much. And the open jeering by citizens in the weeks that followed continued to fuel their resentment. It was said that whenever officers and men left the barracks they were exposed to heckling and ridicule.

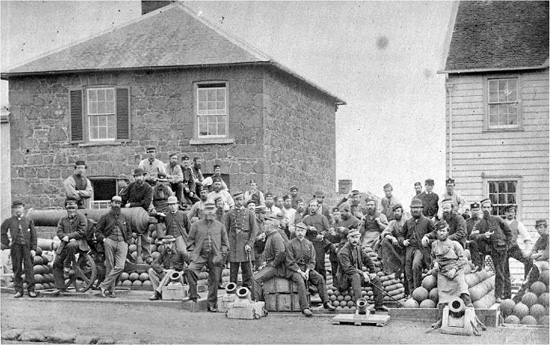

Albert Barracks, a 1860s photograph showing stone and wooden buildings, guns and cannonballs, and men in military and civilian dress. AUCKLAND CITY LIBRARIES, NEG 423.

During the month following the arrival of the North Star, a total of 495 officers and men of the 58th Regiment came into Auckland on the transport schooner Velocity, and the Slains Castle, a barque from Port Jackson temporarily commissioned as a troopship. Perhaps even more reassuring to Governor FitzRoy was intelligence from the north confirming that, in opposing Heke’s rebel forces, he could count on the continued friendly support of the Nga Puhi chieftain Tamati Waka Nene and his followers.

Thus encouraged, the governor persuaded himself that he had become strong enough to resume war against Heke. On 27 April, he despatched a force from Auckland under the command of the much-respected Colonel William Hulme. Every fighting man who could be spared became part of what an early historian, Lindsay Buick, has described as ‘a hurriedly assembled and ill-equipped force’, mainly soldiers from the 58th, a few from the 96th and an informal unit of 50 Auckland volunteers. One hundred and twenty seamen and marines from HM ships North Star, Hazard and Victoria were also to be attached to this force of 350 men once they had disembarked at Kerikeri.

It is not my concern to write about the progress of the Northern War from this point. This story will be confined to a short account of the first engagement, the attempt made on 8 April 1845 by this combined force, assisted by Tamati Waka Nene’s ‘friendly’ Maori, to take Heke’s home pa at Puketutu, beside Lake Omapere.

After a march to the pa, passing through heavy rain on the way, the combined force made its attack using three strong assault parties. There was bitter fighting in the approaches to the pa, which had been hastily but skilfully prepared, and then at close quarters at the pa palisades themselves. But at no point were the palisades breached either by naval rockets or by Pakeha attackers. When it became obvious that the pa could not be taken, Hulme was forced to order a retreat, which his forces were able to carry out only with difficulty despite covering fire from Waka Nene’s men. The British losses were considerable: James Belich’s estimate is 52 killed and wounded.

So, the British failed to take the pa. Their only consolation was that things could have been much worse. Three days later, when Hulme’s force arrived back at Kerikeri, it was greeted with evident relief. Major Cyprian Bridge of the 58th wrote in his journal that the captain of the North Star ‘was delighted to see us all safe, having heard a report that we had been defeated and all cut to pieces’.

By this time Heke had abandoned his pa, intending to place his followers within a more defensible and better-prepared stronghold. When this intelligence ultimately reached Auckland, FitzRoy, sanguine as ever, in Buick’s words ‘was disposed to take a highly optimistic view of the situation’, and to claim that the British had won a moral victory – in short had ‘beaten’ Heke at Puketutu. They had not. But that is no reason to dissent from Buick’s further opinion that the troops had shown ‘bravery, grit and devotion [to orders]’ in what had been a most chastening experience.

Meanwhile back in Auckland settlers were ignorant of the progress of the war, and this, wrote Peter McDonald, kept the people there in a state of ‘constant uneasiness and anxiety’.

Every day there was some new tale causing new trouble. It was the custom for people to go down every evening to the Crescent [Shortland Crescent] to hear the news and talk about the state of the country. Real news was often a very rare matter. But rumour had it all to itself – the inventive qualities of the mind had full scope and a boundless field to work upon. When you went down you heard a yarn. All right, go up a street and return again in half an hour – you heard the story repeated with so many additions that you had hard work to find out whether it was the same [story] you had heard half-an-hour ago. But I suppose it is always the same when you have got only rumour to depend upon for your information.

The first firm news about the opening stages of the resumed war came through when Colonel Hulme and a few troops returned to Auckland on the government brig Victoria, carrying about 40 men who had been wounded during the engagement at Puketutu. The historian Wallace speaks of the consternation of the Auckland inhabitants ‘when they saw the haggard looks and worn-out accoutrements of the soldiers’.

But Rumour was still able to work her mischief. McDonald recalls that during this time of uncertainty, whenever a vessel came from the northern theatre of war, people would flock down to Official Bay ‘in order to gain the first intelligence’. On the day that Hulme’s party returned, John Macfarlane of Henderson & Macfarlane, partners with early interests in commerce, shipping and the hotel trade, was in the forefront of those who rushed to the beach. As the first rowboat from the brig approached the shore, a number of questions were shouted to the boatman including one from Macfarlane, who asked, ‘How did the 96th get on?’ The boatman replied, whether out of mischief or malice it is not clear: ‘Oh, ran away as usual!’ McDonald, who came back to town with Macfarlane, said that as they passed by the Britomart Barracks a ‘number of soldiers looking over the walls … asked us the news, and particularly as to how the 96th got on’. Macfarlane did not linger but, as he passed by, simply repeated without embellishment what he had heard about two minutes before.

When the main body of the 96th returned a few days later, Macfarlane’s comment was repeated to them. For many of the war-weary veterans of that regiment this was the last straw.

On the night of 29 May their resentment exploded. A party of soldiers – one account says a dozen, another as many as 50 – fortified by drink it would seem, and dressed in old moleskin trousers and jackets, left the barracks armed with bayonets and sticks to go on the rantan. They stormed down Shortland Crescent until they reached the hotel owned by Macfarlane and his partner, Thomas Henderson. There, two ringleaders, John Ford and William Gutteridge, began to incite the others to destroy the hotel. Cries went up: ‘Go it 96!’ and ‘Knock the house down!’ The party then began to tear off the sliding shutters and smash the windows.

The rioters would surely have succeeded in wrecking the public house, had it not been for the patrons within, some of them soldiers, led by a young sergeant of the 58th Regiment who had recently arrived from Sydney with a regimental advance party. A bar-room brawl developed, spilling onto the street. John Macfarlane, who was on the premises at the time and was the declared target of the rioters, was saved when he was smuggled out of the rear entrance of the hotel before the rioting soldiers could lay hands on him. The donnybrook came to an end when the regimental commander Hulme, with two senior officers and a detail of the 58th in tow, made an unexpected appearance and quelled the disturbance by ordering the rioters to return immediately to their barracks. After helping to end the riot, Major Cyprian Bridge of the 58th, in whom the fires of regimental rivalry burnt keenly, after helping to end the riot, wrote in his journal in a fit of Schadenfreude that the 96th had been caught up in ‘a disgraceful business’.

Soon after, the police laid charges against four of the soldiers whom bystanders claimed to have recognised. They were tried in the Supreme Court before Chief Judge William Martin on the charge that ‘they being riotously assembled, feloniously began to demolish a dwelling-house’. Colonel Hulme was called on as a witness. The testimony of this well-regarded officer blended a quiet rebuke to the settlers of Auckland with a plea for mercy on behalf of his men. They had been under provocation for some time, he said, and the soldiers were ‘men of good character … who had been very much slandered since the affair at Kororareka’. Two of the accused were acquitted; but the ringleaders Ford and Gutteridge were found guilty and sentenced to two years’ hard labour – a relatively light punishment by the standards of the time. Peter McDonald, whose account of this episode tallies with other documentary evidence, maintained – in a statement I have not been able to corroborate – that the prison sentences were never served. The convicted men, he wrote, ‘were handed over to their own officers for punishment who sent them away, it was supposed, to join their regiment in some other quarter of the world’. If the regiment did indeed ‘take care of its own’ that was an appropriately humane ending to what McDonald called ‘the great riot’.

At this stage our story moves forward nineteen years to an affray of the 1860s that arose out of the Battle of Gate Pa near Tauranga, where the British forces suffered a military defeat perhaps more ignominious than in any other engagement of the decade. But it is not with the battle itself that we are mainly concerned, but its curious consequence in Auckland. In amazing fashion history began to repeat itself. Once again the honour of a unit of the armed forces was called into question. Once again a quarrel broke out between resentful servicemen and their civilian critics. And once again, riotous servicemen set out to vent their fury by attempting to wreck a public building in Shortland Street – as the Crescent, by this later date, had come to be called. And once again the root cause of these recriminations was the settlers’ inability to grasp that military setbacks when fighting Maori came about, not necessarily through British incompetence or cowardice, but through Maori mastery of the craft of war. Knowing the feats of members of 28th Maori Battalion during the Second World War, modern New Zealanders have no such problem.

On 2 May 1864 the New-Zealander carried an account of ‘the most disastrous intelligence from the seat of war’ at Tauranga. It spoke of the failure of an attempt on 29 April to storm Gate Pa (Te Ranga):

by a party of the Naval Brigade under Commander [George] Hay and a detachment the 43rd Regiment under Colonel [H. G.] Booth. The pa was entered, after driving the Maoris from their rifle-pits, under a sharp fire from the enemy, and it was thought by the spectators [who included the commander of the operation General Cameron] that it was taken, when suddenly a terrible fire was opened by the Maoris, and the troops had to retreat leaving the dead and wounded behind. Preparations were then made for formally investing it, but on the following morning the natives evacuated the pa, when it was again entered, and the dead and wounded removed.

Time was to prove that this report was sanitised. Actually, there had been a humiliating defeat. The British losses of officers and men killed and wounded were unusually heavy, and the ‘retreat’ of the joint army and naval forces was in fact a rout. Little wonder that newspapers began to brand this engagement ‘the Gate Pa disaster’. There was a torrent of recrimination, as settlers denounced the leadership of Lieutenant-General Duncan Cameron and his senior officers. Once again there was talk of cowardice.

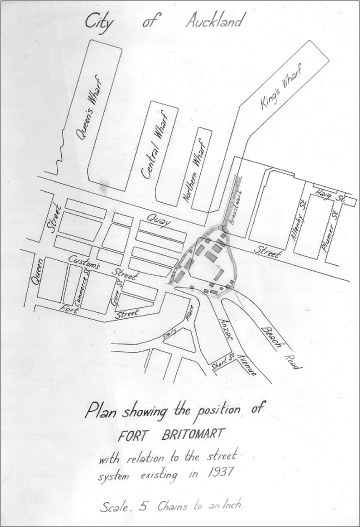

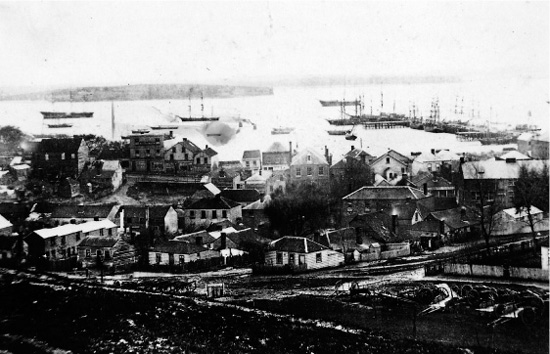

‘View of harbour looking north from Barrack Hill.’ OLD NZ PRINT NO. 5474, AUCKLAND CITY LIBRARIES.

There is no need to explain how what had appeared at first to be a British victory degenerated into a headlong flight. In The New Zealand Wars, James Belich has critically evaluated the competing versions of why the attack failed and his interpretation is convincing. The assault forces were never in true possession of the pa. Concealed Nga Te Rangi warriors, a hardy and resourceful group as they had proved at the famous Battle of Taumatawiwi 30 years before, had enticed the British into a trap and at a crucial moment thrown them out of the pa by subjecting them to withering fire.

A month after the engagement rumours of cowardice found their way into the New-Zealander, which operated out of a wooden building on the southern side of upper Shortland Street. By this time John Williamson was the sole proprietor of the paper, his former partner W. C. Wilson having fallen out with him over Williamson’s pro-Maori sympathies and gone on to form his own paper the New Zealand Herald. Williamson was, in the phrase of the time, a ‘Philo-Maori’, a member of a resolute minority of Auckland inhabitants, such as Bishop Selwyn, the interpreter C. O. Davis, William Swanson, who was married to a Maori (Hauraki) chieftainess, and George Graham, who had supervised the construction of many of Auckland’s military installations. Because of Williamson’s pro-Maori sympathies any criticism of the war effort that appeared in his paper was particularly suspect to the firebrands of Auckland.

On Saturday, 4 June, the New-Zealander carried an apparently innocuous article submitted by ‘a special correspondent’ entitled ‘A Visit to Te Papa Cemetery’. The piece spoke of four tombstones at Te Papa – site of the camp near Tauranga from which the assault on Gate Pa had been launched – that had been erected to the memory of four fallen naval personnel. One grave was that of Captain J. F. C. Hamilton, of HMS Esk, who had died of wounds sustained during the assault. The correspondent remarked that:

It is much feared that this brave officer was cruelly deserted by his men, who were seized with a panic and fled back to our position after being gallantly led as the forlorn hope to the attack. It is true it was a critical moment, but if the men had displayed half the courage and daring of their officer, a very different result would have to be chronicled respecting this unfortunate encounter.

By the day this article was published, HMS Esk, a steam corvette with twenty 8-inch guns, had returned to Auckland from Tauranga. The crew were infuriated by the New-Zealander’s criticism. Sailors living in a manifestly male environment and subject to the rigours of a life at sea were notoriously sensitive to any impugning of their manliness. After their Sunday service, the ship’s crew was granted shore leave. As they disembarked, however, their hearts were not full of Christian charity, but of schemes to exact retribution.

On the following morning, shortly before ten o’clock, a mob of about 50 men bearing hauling tackle, who had come ashore from HMS Esk and her sister ship HM sloop Eclipse, then also in port, marched up Shortland Street to the offices of the New-Zealander. Their spokesman, quartermaster John T. Beckett, described in one account as black, invaded the office and demanded that the clerk on duty reveal the identity of the reporter who had written the article on the Te Papa Cemetery which, he said, had defamed the sailors. The clerk was unable or unwilling to oblige. The seamen then demanded to see John Williamson, the owner-editor, a pugnacious Ulsterman. He surely would have tried to repel the invasion but he was not in his office.

At that point the men took steps to administer their own rough justice. With block, tackle and hawsers, they made preparations to pull down the wooden weatherboard building that housed the New-Zealander, by passing a cable through the windows on either side of the upper storey, then taking it over the roof. Once the building was thus lassoed, an alarmed reporter pleaded for a stay of execution. He appeased the sailors by promising to publish forthwith their version of their part in the retreat from the pa. The raiding party agreed to let the building stand for the time being but they departed with the threat that unless a retraction was published by noon, they would return and destroy the premises.

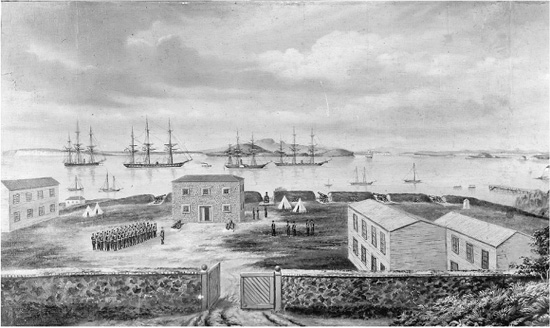

‘Auckland Harbour 1869, looking north with Fort Britomart in the foreground, showing HMS Blanche, Challenger, Virago, and Charybdis, on the occasion of the visit of the flying squadron. (From a drawing by Sam Stuart.)’ AUCKLAND CITY LIBRARIES, NEG. W473.

Later in the morning Beckett and his men came back with a written account concocted by the quartermaster which, they insisted, must be published verbatim. In this the sailors maintained they had not deserted Captain Hamilton but were still surrounding him at the moment he had been mortally wounded on the ramparts. Their version ended by shifting the blame for the headlong retreat of the Naval Brigade from the pa onto the army: the 68th Regiment had caused the panicked withdrawal when its soldiers, rushing in on the opposite side of the pa had given the impression of a renewed Maori attack.

At the time of Beckett’s second visit to the New-Zealander, a bystander observed in a stage whisper that ‘It is easier to take a printing-house than a pa’. The quartermaster lunged at his tormentor but succeeded only in breaking an office window.

As promised, the newspaper published the sailors’ statement in a special midday edition. By this means the New-Zealander was saved. But was the honour of the Naval Brigade from the Esk, Miranda and Falcon saved as well? Williamson reported his account of the episode in a later edition under the ironic caption ‘The Pomp and Circumstance of Glorious War’. And shortly after, The Times of London dismissed the statement of the crew of the Esk as ‘ridiculous’. And it surely was, if we believe the word of a 22-year-old naval officer who took part in the engagement, Lieutenant Clark, later in life to be Rear-Admiral Sir Bouverie Clark. His entry in the logbook of HMS Esk for 30 April 1864 tells not of honour but of shame that spread far and wide. ‘All say the men, with very few exceptions behaved disgracefully; the panic seems to have been universal, and soldiers and sailors all ran as hard as they could pelt out of the pah, when a few seconds longer would have established themselves well in it.’ In fairness to the soldiers and sailors it must be said that Clark’s last assertion, that the pa could have been held had the British kept their nerve, flies in the face of attested knowledge that the British forces inside the pa were confronted by an irresistible Maori counter-attack from the trenches within.

The New-Zealander ceased publication in 1866 but it collapsed because of a dwindling circulation. A sailor’s rope had not pulled it down.