John Logan Campbell, businessman, philanthropist and donor of Cornwall Park, was also a patron of the visual arts. He founded and funded Auckland’s first school of art and was an inaugural member of the Mackelvie Trust, which helped to create the city’s first art gallery. These achievements have contributed to the high regard in which the Father of Auckland has long been held.

This story tells of something much less well known – how an unusual friendship lay behind Campbell’s decision to set up his school of art. Moreover, few people in today’s artistic community are aware that although Campbell’s scheme came to fruition in Auckland in 1878, the seed had been planted fourteen years before in Italy. That’s where he first struck up his friendship with a young American, Pierce Francis (Frank) Connelly (1841–1932).

The nineteenth century abounds with well-publicised instances of strong, emotional male friendships, most of them seemingly devoid of any conscious homoerotic overtones. One such friendship existed between the poet Alfred Tennyson and Arthur Hallam, whose premature death at the age of 22 drove Tennyson into prolonged grieving and ultimately inspired his lengthy elegiac poem ‘In Memoriam’.

Throughout his long life Campbell remained a reserved, undemonstrative man. Yet, at crucial stages, three male friends commanded his loyalty and affection to an unusual degree. The first in sequence was a fellow pioneer, Hastings Atkins: ‘my adopted brother’ the youthful Campbell called him; ‘my dearest, kindest and best friend’ was how Atkins regarded him in return. Then there was Frank Connelly, the young American artist whom the middle-aged Campbell befriended in Italy. Finally there was Alfred Bankart, the youthful factotum who managed Campbell’s business affairs during his declining years. Of these three friendships the one with Connelly was the most intense.

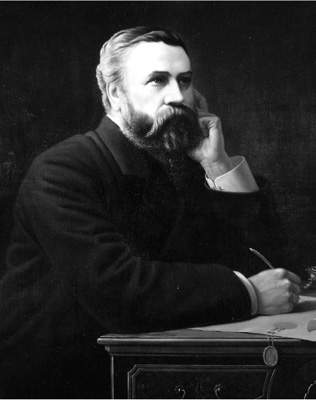

James Tannock Mackelvie, 1814–85. Portrait, oil on canvas, 1892, by Louis John Steele, based on an earlier photograph. While acting as a resident partner in Brown Campbell & Company, Mackelvie amassed a considerable fortune through investment in Thames gold mines. Upon his return to Britain Mackelvie became a connoisseur and collector of art. In his will he bequeathed a considerable portion of his collection and private fortune to a trust which would establish and maintain a ‘free museum of art for the people of Auckland’. Campbell was a reluctant foundation member of this trust that remains a benefactor of the Art Gallery to the present day. AUCKLAND ART GALLERY TOI O TAMAKI.

Twenty-five years ago, while I was researching the middle years of Campbell’s life, a colleague, Eric McCormick, drew my attention to the fact that Henry James’s first full-length novel, Roderick Hudson, replicated in fiction many of the essential features of the Campbell–Connelly friendship. In this novel a wealthy businessman, Rowland Mallet, becomes a patron of the arts and takes up the eponymous young American sculptor as his protégé. Mallet finances Hudson to go and live in Italy, convinced that its stimulating cultural environment would transform a precocious artist into a ‘notable sculptor’.

It was in Italy that Campbell first met the young artist friend and, as their friendship deepened, was encouraged in the hope he would become, as Campbell worded it, a ‘second Raphael’. In James’s novel the patron’s expectations are not realised. Italy distracts rather than ignites Hudson, brings on a latent mood of irresponsibility and a promising artistic career is cut short by death. Similarly, to Campbell’s despair, Connelly proved wayward; the fine promise remained unfulfilled, his artistic life ended not by accidental death but by indolence. Or so Campbell believed.

Fully to understand the nature of the Campbell–Connelly friendship one must be aware of certain elements in the background of the men involved. Campbell quickly became a wealthy man. But he was no philistine. After qualifying as a doctor he continued to read widely. Yet, believing his self-education incomplete, he yearned to return to Europe in order, as he put it, ‘to tread the enamelled spots’ of the Old World. In 1848 he was sufficiently well off to undertake ‘the Grand Tour’ (his term) on which he had long set his heart. Two years of wandering through the Ancient World and through Europe proved to be a personal revelation. He learned that he was, artistically speaking, an ignoramus. This deficiency he set about strenuously correcting, particularly between 1857 and 1870 when, apart from one brief interlude, he spent his entire time as an expatriate resident in Europe.

The art galleries in, or close to, London, Paris, Venice, Florence and Rome were his special haunt. He became acquainted with the works of many masters and, for one largely self-taught, acquired a sound if somewhat unadventurous taste in traditional art. He also developed a lofty, if overripely sentimental conception of the role of the artist in society. Neither this idealistic view of aesthetics, nor the enthusiasm for fine arts in one so unabashedly imbued with the materialistic business ethic of the age was peculiar to Campbell. Such passions were common among many businessmen and industrialists in Britain and, especially, the United States in this heyday of industrial capitalism. An idealised notion of the high status of the artist was indubitably an important element in Campbell’s admiration for the 23-year-old sculptor when their paths crossed in Florence during 1864.

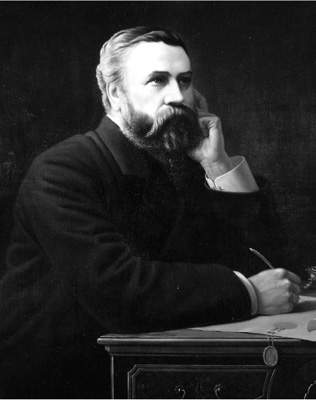

Connelly was an impressive young man, even apart from his prowess as an artist. He was intelligent, darkly handsome, adept in four languages, a fascinating conversationalist, and a fine singer. Few were not charmed on first meeting him. Campbell was no exception. In spite of a 24-year age gap the pair quickly became close friends.

Connelly’s entry into sculpture had not been by an orthodox route. After a public school education in England at Marlborough College, he had trained as a painter in Paris at the École des Beaux Arts, in Germany and in Rome. Then, shortly after coming to Florence with his father and sister, he fell under the influence of the American sculptor Hiram Powers, who was living there, and decided that he too would turn to sculpture. For one without training in the plastic arts, he quickly revealed an abundant and precocious talent. But if his rise was meteoric so also was his decline. Connelly lived to be 91, dying in Rome in the home of his daughter, the Princess Marina Connelly Borghese, but almost all his creative work of consequence was executed between the ages of 23 and 40 – roughly the years, coincidentally, of his friendship with Campbell.

Frank Connelly: an undated photograph, but almost certainly taken about the time he visited New Zealand in 1877–78. AUCKLAND WAR MEMORIAL MUSEUM, NEG. M192 (25).

Why an artist of such exciting potential in his youth should have become, during his extended later life, a figure of unfulfilled promise is, on the surface of things, puzzling. It also puzzled Campbell in his old age, and disappointed him – bitterly. By that time, however, Campbell had concluded that although Connelly was an ‘inborn genius’, he was flawed by a lack of self-discipline: a ‘regular Johnny Head in the Air’, ‘a damned Harum Scarum’ whose ‘character, alas, revealed itself in the wrong direction’. This simple moralistic diagnosis of what one might call a prolonged ‘artist’s block’ is scarcely supported by the evidence. Beneath an unruffled, even happy-go-lucky surface, Connelly was psychologically unstable to an unusual degree.

If Campbell, even in hindsight, found Connelly’s personality baffling, we, living in a post-Freudian age, need not. It would be difficult to imagine a more bizarrely disturbed childhood. His troubles really began back in Louisiana in 1840, a few months before he was born. When his mother Cornelia was four months pregnant, her husband Pierce, until recently the Episcopalian rector of a Natchez parish but now a convert to Rome, appealed to her to join him in adopting a celibate life. This for Pierce was to be a preliminary step towards the dissolution of their marriage, which would enable him to be ordained a Catholic priest. Cornelia, by now a devout Catholic, readily agreed. Early in 1842 she entered a convent, taking the infant Frank with her. Shortly after Pierce’s ordination as a Catholic priest in 1845, Cornelia, who had already taken the vow of chastity, founded the Order of the Society of the Holy Child Jesus.

However, in 1848, Pierce had second thoughts about his vocation. He renounced his new priesthood, gathered his children, including Frank, about him once again, and filed a suit in the English courts against Cornelia for the restitution of conjugal rights. After a long delay, judgment in what was generally regarded, at the time, as an unseemly case, if not a public scandal, was found in favour of Cornelia. Thus except for his years of infancy, Frank was brought up separately from his mother, in an atmosphere of parental confusion and contention, and in a whirl of constant peregrination between America, England and Italy. After the collapse of his scheme for reconstructing his marriage, Pierce Connelly rejoined the Episcopalian ministry. But, from that point on, all his worldly ambition became concentrated on his talented son, Frank. After over a decade of trauma, the boy now became hopelessly petted and indulged, with what psychic consequences may easily be imagined. It is surely significant that when Frank reached adulthood he became bitterly anti-Catholic.

But as Campbell’s friendship with Connelly ripened in Florence between 1864 and 1867, he seems not to have noticed anything unusual about the younger man’s personality, Indeed, he developed such unbounded confidence in the sculptor’s talent that he decided to become Connelly’s patron. Encouragement took the form of hard cash. Early in 1867 he advanced £1400 sterling so that the artist could shift from his poky little workroom beside the Piazza San Spirito near the left bank of the Arno to a grand studio in the Via Nazionale, where he could, in Campbell’s words, ‘undertake his great works and work out his noble conceptions’. Nor was the relationship between patron and protégé narrowly formal. In his later reminiscences, Campbell recalled the many happy hours he spent chatting to the young sculptor as he worked away in his studio, or as they walked of a summer evening along country lanes north of Florence to Campbell’s leased residence, the palatial Villa Capponi, where Connelly was a constant guest.

A posthumous bust of the infant Logie Campbell, 1864–67, who died during an epidemic in Florence at the age of 32 months, and who was buried in the Protestant cemetery of that city. This bust was sculpted by Connelly to comfort the bereft parents. GODFREY BOEHNKE, UNIVERSITY OF AUCKLAND.

The death of Campbell’s only son Logie as an infant of 32 months gave the relationship an even deeper intensity, with, in Campbell’s case, morbid overtones. Before the burial took place in February 1867, Connelly modelled in clay a bust of the dead child which he later reproduced in marble to comfort the grieving parents. Years later Campbell wrote of the burial itself in portentous terms. ‘In the English [Protestant cemetery] Campo Spirito in Florence, lies buried our only son. Frank Connelly stood by my side as we lowered him to his last resting place while the funeral service was read by dear old Mr Connelly; & as we three stood I believed I had found another son in the youth who was at my side.’

The mutual affection and regard of the two men held up over the next ten years despite their having very little opportunity of seeing one another. Campbell returned to New Zealand in 1871. But his feelings towards Auckland remained ambivalent. He needed to stay in the colony to maintain his firm’s pre-eminence, and with that, keep his income intact. Yet Europe, its culture and its cosmopolitanism, still drew him. And so did Connelly. ‘I looked on this bright young genius almost as a son,’ he confessed to a friend in the mid-1870s, ‘so much so that not so very long ago I contemplated changing the whole tenor of my life & leaving NZ & taking up my home on Italian soil to live beside the very man.’ But the demands of business kept Campbell chained to his office desk in Shortland Street. His next meeting with Connelly took place not on Italian soil, as Campbell had once dreamed, but in Auckland itself, and it came about almost by chance.

Connelly, like a number of artists resident in Italy, had decided to go and exhibit in the Centennial Exhibition of the American Republic held in Philadelphia in 1876. He made a number of sculptural submissions, groups and single pieces in marble and bronze, eleven items in all. Although one of his works took a top silver award and his pieces received some critical acclaim, he was disappointed with the financial outcome of his venture. He received little in the way of hoped-for lucrative commissions, either at the exhibition itself or during the following year as he travelled through the United States. ‘Disheartened and out of pocket’, as he later reported to Campbell, he looked back upon ‘the Ph. C. Exhibition’ as ‘a humbug’.

Campbell, on his own while his wife and daughters were in Europe, thought that this domestic situation provided an ideal opportunity to invite Connelly to visit New Zealand. As an inducement, he offered to pay the young man’s fare from the States. In August 1877 Connelly arrived in Auckland. Although the friends had not seen each other for seven years they quickly slipped into their old affectionate relationship. They were on Christian-name terms – very few outside Campbell’s immediate family ever presumed to call him ‘Logan’. Campbell was obviously gratified to have the company of a man whose presence reminded him of his former idealised European existence. Locally, Connelly was lionised, hailed in the press as ‘the eminent sculptor’.

Once the artist was installed in Campbell’s house overlooking the harbour, his flagging spirits were soon restored. Campbell imagined that this new environment would encourage the artist to resume sculpting. But this did not happen. Connelly pushed sculpture aside and turned to his first love, painting. Campbell’s memoirs tell us why:

The scenery which surrounded him at once cooked his artist nature within him and before I could well turn around, Logan Bank verandah, which could be completely closed in by sliding windows was converted into a studio and easels, and palettes and brushes were the order of the day. I took him to Rotorua to see the [Pink and White] Terraces and one day I held an umbrella over him as he sketched Tikitapu the Blue Lake from which study he afterwards painted the beautiful picture now hanging on the drawing room wall.

During the eleven months that Connelly stayed in New Zealand, he made three separate excursions to paint scenery: to the Hot Lakes, to the Tongariro–Ruapehu mountain area and to the Southern Alps and the fiords. After the first and third excursions he returned to Logan Bank with notebooks and oil sketches, ready to commit his ideas to canvas.

From the second excursion, however, Connelly came back empty-handed. He had been given permission by the great chief Rewi Maniapoto to enter the Kingite domains as a special concession. But he abused his position of trust by climbing Mount Tongariro, regarded by Maori as very deeply tapu, in order to make sketches of the scenery ‘on the sly’. On Connelly’s descent, irate Kingite Maori warriors seized and bound him, confiscating his equipment, horses, sketchbooks and paintings. An acquaintance of Campbell wrote informing him that the artist had no reason to consider himself hard done by. In view of the gravity of his offence, Connelly was in fact ‘lucky at getting away with a whole skin’. Had it not been for the intercession of the European guide who had brought him into the King Country, C. O. Davis, a philo-Maori of good standing with local tribes, Connelly could well have been killed.

And, artistically speaking, all had not been lost. In a letter to Connelly’s sister, Adeline, Campbell reported that the artist had no sooner arrived back in Auckland than he set about ‘painting like a hurricane’, reconstructing his mountain landscapes, relying on images of the scenery while they were still vivid in his mind’s eye. The Tongariro escapade was reported in newspapers from one end of the colony to the other, converting Connelly into what we would now probably call a celebrity or, as Campbell put it, making him almost an item of ‘public property’.

After the later, extended southern tour, Connelly spent the last two months of his New Zealand sojourn at Logan Bank. Once again, said Campbell, he painted at a ‘hurricane pace’, this time from his sketches of the Southern Alps and fiords. Consequently, before he left the colony he had, close to completion – to be finished off in his studio in Florence – ‘some twenty large oils to carry away besides all his small studies’.

The week before he left for Sydney, Connelly held an exhibition of his New Zealand work, even though he knew that some paintings lacked ‘completion in detail’. Campbell called this showing an ‘At Home’, which in a sense I suppose it was, since it took place in the main public rooms and on the closed-in verandah of Logan Bank – ‘a perfect gallery’, said Campbell proudly. Excerpts from the letters that the merchant sent to friends abroad best describe this occasion, which was attended by 90 viewers. The purpose was ‘to allow Auckland to see the prolific productions of my friend Connelly’s brush, a rare and beautiful collection of N.Z. landscapes’. Not that Campbell imagined Auckland had reached artistic maturity. Such a pity, he mused, ‘that only two persons [Connelly and Campbell?] understood [the] display placed before them’. To Connelly’s sister, he continued in the same vein: ‘[this] wonderful and very beautiful collection of views will be … much more appreciated out of the colony than in it. Few here have any cultivated taste in art – no chance of acquiring that in fact & one feels that the beauty Frank’s pictures ought to have offered has been thrown away.’

The Fresco Room of Kilbryde, Parnell Point. The frescoes painted by C. H. Kennett Watkins, over 1880–1, were strongly evocative of Campbell’s treasured life in Italy and Switzerland. In 1878 Campbell appointed Kennett Watkins as the first director of the free school of art he set up. CAMPBELL COLLECTION, AUCKLAND WAR MEMORIAL MUSEUM.

Very few of the paintings remained in New Zealand. The greater part were bundled up and sent on to Florence. Their whereabouts today is a mystery. Inquiries that I made about 20 years ago suggested that surviving pictures were stored in the basement of the home in Rome of one of Connelly’s descendants – subsequent to his New Zealand visit he married an Italian woman.

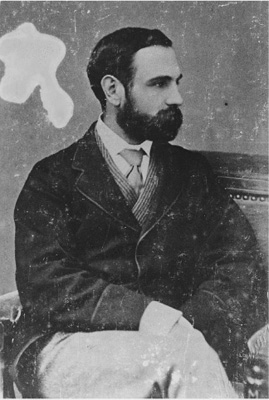

‘J. Logan Campbell Esq.’ A photographic copy of a portrait of Campbell in oils painted by Connelly during his 1877 visit. Campbell praised the original painting, which has been lost, as ‘a living likeness’. AUTHOR’S PRIVATE COLLECTION.

The Campbell–Connelly friendship did not survive the 1877–8 visit. In spite of Campbell’s pride in what Connelly had achieved artistically in the colony, the relationship had permanently soured. As with Trollope so with Connelly: Campbell had unreal expectations of his guest, could not see him as the fallible human he was. Predictably, disillusionment set in over money matters well before Connelly left. The reality was that the artist had sold few sculptures in recent years and had already been hard up by the time he came to the colony. Needing to borrow from Campbell, he did so lightheartedly, at the same time neglecting, as Campbell noted, to thank his Auckland patron for his generosity in years gone by. Connelly was in fact, in such financial straits that he had to rely on Campbell for drafts to finance his peripatetic progress through New Zealand, and even to pay for his passage back to Italy. After Connelly left, a series of exasperating accounts he had run up also ended up for payment at Logan Bank.

As for Trollope, so for Connelly: Campbell footed all unpaid bills. But friendship paid the price. He decided that Connelly had treated him like a milch cow. Nor was he in a mood to be indulgent. Bohemian improvidence, overlooked in Florence as an aspect of the artistic soul when Connelly had been in his twenties, Campbell was no longer prepared to put up with in Auckland now that Connelly was rising 40. Campbell regarded his protégé’s fecklessness, ingratitude and self-absorption as unforgivable.

But while the visit may have killed the friendship, it gave birth to a school of art in Auckland, and provided an impetus and a new direction to the city’s artistic affairs.

Years later, the young artist C. H. Kennett Watkins recalled that when Connelly came to Auckland, ‘art matters were in a very chaotic state’. The fledgling Auckland Society of Artists, in spite of having members of considerable potential, was little more than a self-doubting coterie. Then came Connelly, acclaimed as ‘a great genius’, a sculptor of ‘known fame and reputation’ whose ‘whole life has been devoted to art’.

At this critical juncture, Connelly proved his worth. Although lionised, he was anything but lofty. Towards local artists he showed generous encouragement and sympathy. Shortly after he arrived, he went along as ‘visitor’ to a tiny meeting of the Society of Artists. It was typical of him that at the society’s next exhibition, in November 1877, he should join local painters such as J. B. C. Hoyte, Alfred Sharpe and Albin Martin in submitting a number of items. His contribution included photographs of some of his own overseas sculptures, a series of sketches, two portraits, including one of ‘Logan Campbell Esq.’ which the proud subject extolled as a ‘living likeness’, and two landscapes including that of Lake Tikitapu, which he had painted under Campbell’s parasol. Even those items, which Connelly admitted were ‘unfinished’, revealed, in the opinion of a star-struck Herald reporter, ‘great artistic insight’.

Connelly also impressed the Auckland artistic community by proffering what we today would regard as a piece of enlightened advice. Local artists, he counselled, should not continue to reproduce the art of Europe in an antipodean setting. ‘The climate and scenery in New Zealand’, he reminded colonial artists, ‘are especially favourable to the growth of a distinct school of art.’ This may seem to be a self-evident observation today: it was much less so 130 years ago. Characteristically, Albin Martin’s depiction in oils of his Tamaki farm some years before looks suspiciously like an Italian landscape painting.

There is little doubt that it was Connelly’s presence in the colony that led to Campbell’s decision early in 1878 to found in Auckland what he called his ‘school of design’. However, he delayed publicly announcing his intention until the middle of the year when a gift coming from Thomas Russell, the wealthy expatriate in London and Campbell’s personal friend, provided the perfect opportunity to act. In May 1878, Russell wrote to Campbell informing him that he was shipping out, as a presentation to the Auckland Institute, 22 life-sized plaster of Paris statues, copies (with two exceptions) of ‘the most celebrated antique originals, and twelve plaster busts’.

Campbell wrote back, asking if he could be associated with the project and promising that ‘as the Institute is impecunious I shall stand paymaster in all that is concerned in properly mounting the statues & busts on pedestals’ in the institute’s building. He wound up this letter with a further declaration of intent: ‘I hope to follow this valuable presentation of yours to the legitimate end – the forming of a School of Design’. Russell and the institute were only too happy to agree to this benefaction. Campbell acted swiftly and appointed Kennett Watkins, who was another protégé, director of his proposed new school.

Once his offer was accepted, Campbell sent to the institute’s council room in Princes Street ‘drawing boards and tables, cases, easels, and all the requisite furniture, together with a large number of fictile [pottery] studies’ – such items as miniature portions of classical columns and of the Elgin marbles, together with models of various portions of the human body.

On 2 November 1878, Watkins put 26 candidates through a drawing test for entry into the new school of design. Fourteen, mainly young women, passed and became the foundation pupils of the Campbell Free School of Art. For the next eleven years Campbell presented annual prizes in the form of silver medals to the most able students. He also supported the school from his own pocket until 1889 when a bequest from Dr J. E. Elam, a wealthy medical man with an interest in fine arts, enabled him, at a time of personal financial straits, to shift the burden onto other shoulders.

By then Campbell and Connelly were no longer friends. But his admiration for Connelly’s work survived. Today there are only five Connelly paintings in the Auckland Art Gallery, all donated by Sir John Logan Campbell in the early twentieth century. But unhappily none was painted during Connelly’s New Zealand visit.