The past is not dead. It’s not even past. – William Faulkner

One summer afternoon just on 100 years ago, two small boys who had been playing overlong on the sands of Judge’s Bay scrambled up the cliff at Campbell’s Point to take a shortcut home. Unknowingly they were entering the grounds of Kilbryde. There they met an ancient white-bearded man shuffling along a path, feeling his way with a walking stick. Seventy years on, one of those boys, now himself an old man, recalled that Sir John Logan Campbell did not give them the ticking off they expected. Instead, in the still broad accent of his youth, he chatted to them in a kindly manner before wishing them well on their way. His Scottish brogue, his frailty and friendliness were the boys’ lasting impression.

What the boys would not have known was that serenity, supposed solace of the old, had eluded Campbell in his last years. In spite of assured wealth and constant adulation, he was prone to lament having outstayed his time. In the closing pages of his last set of memoirs completed in 1907, he wrote

I have laid to rest fellow pioneers so much younger than myself, and when am I to be laid at rest? And there is the feeling within me that I am out of joint with the present day and that it is moving ahead [in a way] that grates upon the quietude enjoyed in earlier days.

‘Campbell’s Point and Judges Bay.’ AUCKLAND HARBOUR BOARD COLLECTION, NEW ZEALAND NATIONAL MARITIME MUSEUM.

His poignancy was deepened by an awareness that he, the Father of Auckland, was less than father in his own family. His wife Emma, though considerably younger than he, had been semi-invalid for years. And three of their four children had died before adulthood. The survivor, Winifred, was a disappointment to her parents. Even after her marriage in England had irreparably broken down by 1900, she declared she would never come back to live once more in New Zealand.

Campbell had not expected such bitterness to accompany his last years, years that had begun so well. He had been a great survivor of the slump of 1886–95. Shrewd investment in provincial land and good profits from a flourishing brewery business – the Domain Brewery near Newmarket – helped him to ride out the economic storm that had overwhelmed so many others of Auckland’s first business élite. But his own indefatigable efforts also helped to save him. In 1893, at the age of 75, when commercial morale was at its lowest in Auckland, he assumed single-handed control of Brown Campbell & Company (BC&Co.), working at the firm’s office at the corner of Shortland and O’Connell Streets daily from 8 a.m. to 6 p.m. By 1897 the firm had become sufficiently profitable for him to negotiate on equal terms with Louis Ehrenfried, by then mortally stricken, to amalgamate the profit-earning liquor side of his firm with Ehrenfried Brothers. By forming The Campbell & Ehrenfried Company, the new partners created the largest brewery concern in the colony. That firm survives today as Lion Nathan.

‘Sir John and Lady Campbell in the Grounds of their Beautiful Home Kilbryde, Parnell.’ NEW ZEALAND GRAPHIC, 26 MAY 1905, P. 5. AUCKLAND WAR MEMORIAL MUSEUM, NEG. C18,763.

Campbell had made Alfred Bankart, his 26-year-old protégé, responsible for handling the BC&Co. side of the merger. It is significant that in three of the great defining commercial initiatives of his life Campbell remained in the shadows and used go-betweens to clinch his deals. James Farmer acted as his agent in 1853 to buy the One Tree Hill estate when it was put up for mortgagee sale; in 1878 Frank Connelly to buy the land on which he was to build Kilbryde from William Swainson (from whom Campbell was estranged), and now Bankart in this last great business deal. Arthur Myers, whom Campbell soon learned to trust implicitly, youthful nephew of the ailing Louis Ehrenfried, acted for the other party. Campbell, now in his eightieth year, was completely satisfied by the merger, which he declared ‘was destined to relieve me of all my financial difficulties, thus bringing me peace of mind which for nearly twenty years had been unknown to me’.

Although chairman of directors in the new concern, he had a business role that was nominal and decorative rather than onerous. Myers was effectively executive manager of the company. Bankart, also a director in the new firm, remained Campbell’s personal secretary and guardian of his remaining business and burgeoning philanthropic interests. This enabled Campbell to immerse himself, until 1901, in his preparations to hand over to the community the land that was to become Cornwall Park, and thereafter until August 1903, when the park was officially opened, to supervise the planning and preparation of its grounds. But once that was done, perhaps because long ingrained habits proved unbreakable, he continued to turn up at his old office every weekday to work at the small deal table from which he had conducted his commercial affairs for over half a century. But with BC&Co. stripped of its brewing and wine and spirits business, all that was left for the old man to oversee, was the dwindling remnant of his once extensive importing agencies.

Alfred S. Bankart, 1870–1933. Bankart joined Brown Campbell & Company as a junior clerk, but quickly rose to become Campbell’s personal factotum in the old man’s declining years. An original trustee of the Cornwall Park Trust Board, and chairman of the board at the time of Campbell’s death, he also played an important part in the erection of the Auckland War Memorial Museum. Once Arthur Myers entered national politics shortly before the Great War, Bankart became the driving force behind the Campbell & Ehrenfried Company and its allied liquor interests. AUTHOR’S PRIVATE COLLECTION.

To fill in his now abundant spare time he decided to bring his reminiscences up to date by writing ‘My Autobiography: a short sketch of a long life, 1817–1907’. This very readable version of his life must be regarded, however, in view of its highly selective nature, as a pre-emptive strike against less flattering biographies which posterity might throw up after he had gone. And Campbell did not ‘write’ it in any literal sense: he dictated what he wanted to say to an amanuensis, a Miss Burton, whom he had employed to transcribe his precise words in her rather immature copperplate writing.

By this time, Campbell’s sight had become so bad that he was forced to abandon his beloved hobby of photography, at which he had developed a considerable skill. In despair over his deteriorating eyesight, he arranged to go to Dunedin and place himself in the hands of the country’s foremost eye surgeon Dr H. Lindo Ferguson, to have cataracts removed from both eyes, a major operation in those days. After Campbell’s ten-week spell in a Dunedin private hospital, an experience he spoke of as ‘damnable purgatory’, his surgeon told that his sufferings had been in vain. Removal of the cataracts had simply revealed what had hitherto been hidden – severe and incurable retinal degeneration.

Campbell returned to Auckland in turmoil to attend an Empire Day ceremony in 1906, at which a large elevated bronze statue of himself in mayoral robes was unveiled at the Market Road entrance to Cornwall Park. It was on this occasion that Campbell made his promise to erect, on the summit of One Tree Hill, an obelisk to commemorate the Maori people. Honoured on all sides at the time, he was publicly acclaimed ‘Auckland’s Grand Old Man’ and ‘a venerable figure as familiar to Aucklanders as Mount Eden’. In the following month, however, Dr Ferguson’s bleak prognosis was more than realised when a sudden haemorrhage left Campbell virtually blind.

In the remaining years life lost much of its savour. Benefactions continued but beyond that he experienced little joy. Once the most prolific of correspondents, he could now attach his signature to documents only from memory. And he, who had prided himself on his ‘juvenility’ (his term) and self-sufficiency, was forced into an unpalatable dependence on others. After the autobiography was finished in 1907, Miss Burton was kept on in his office, primarily as a reader. But when she offered to read from the classics which had once been his delight he turned her down, muttering, ‘No time! No time!’ He reminded her that she must confine her efforts to reading to him the commercial and shipping columns of the Herald. To this diktat, recalled Miss Burton, he made one exception. After Austria–Hungary’s annexation of Bosnia–Herzegovina in 1908, he insisted that she read in full any cabled news from that trouble spot. His personal experience of the Balkans seems to have given him some sense of foreboding. For it was the assassination of the heir apparent to the Austrian throne in Sarajevo, capital of Bosnia, two years after Campbell’s death that precipitated the 1914–18 war.

Campbell died on 22 June 1912. His death certificate was non-committal, giving old age as the cause of death, although it seems that, the week before, he had suffered some sort of stroke. His passing signalled the end of an era: the Auckland Star carried the headline ‘The Passing of a Patriarch’. There was unprecedented public mourning in the city. On the day of his funeral, flags on all government and commercial buildings flew at half-mast. He was buried just as he had wished on the summit of Maungakiekie, the extinct volcano he had christened One Tree Hill on the memorable day he had crossed the isthmus 72 years before.

As the last survivor of Auckland’s foundation years, Campbell retained right to the end of his life a vivid visual image of the Tamaki isthmus as it was when he first landed in April 1840. But for us today, the isthmus has been so transformed over the years that we have to make a great imaginative leap to visualise what the landscape was like before colonisation began.

Reclamations carried out over the last century and a half have utterly changed the southern shoreline of the Waitemata. In 1840, from St Heliers to Herne Bay was a succession of arcuate shelly beaches save where bays, with their mangrove-fringed estuarine reaches, bit deeply into the land. Most dramatic has been the transformation of the foreshore of the inner city where first settlement began. Take the shoreline where Queen Street is now. To the east it ran roughly along Fort Street, then called Foreshore Street, while to the west the beachfront was at Swanson Street. Further west, was the large tidal bay that we call Freeman’s Bay, now completely reclaimed, but from which, in bygone times, Maori launched their canoes at high tide for shark fishing.

Much reclamation had already taken place during Campbell’s time. But the process continued after the First World War. To the west, during the interwar years, land was wrested from the harbour to form the area currently known as the Western Viaduct and Tank Farm. Reclamation after 1945 saw Shelly Beach and the greater part of St Mary’s Bay disappear with the construction of the leisure boating facility known as Westhaven, and the building of the motorway approaches to the harbour bridge which was opened in 1959.

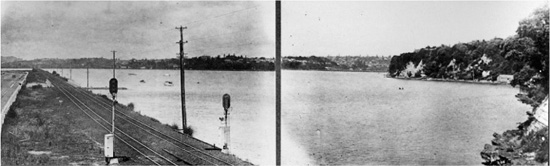

Just as completion of the bridge was to revolutionise settlement on the North Shore, so earlier reclamation to the east of the city resulted in sweeping demographic and economic changes there. First in sequence were two major public works carried out in tandem during the 1920s at Hobson Bay. These were Tamaki Drive, opened in 1931, and what was then called the Main Trunk Line Deviation, constructed to provide alternative major rail access to Auckland, branching from Westfield via the Purewa Valley and Hobson Bay. This revolution in local transport amenities opened up the now densely settled eastern suburbs, which previously, though physically close to the city, had been extraordinarily inaccessible. Sadly, Campbell’s Kilbryde, which had acted as an emergency hospital during the 1918 influenza epidemic, was a casualty of these works: Campbell’s Point was truncated to make way for road and rail, and the grand house itself was demolished in 1924. Much later, reclamation was also the prelude to the development of the container wharf complex of which the Fergusson Wharf, opened in 1969, is the nerve centre. Containerisation served to consolidate the position of Auckland on the Waitemata as the premier port of New Zealand.

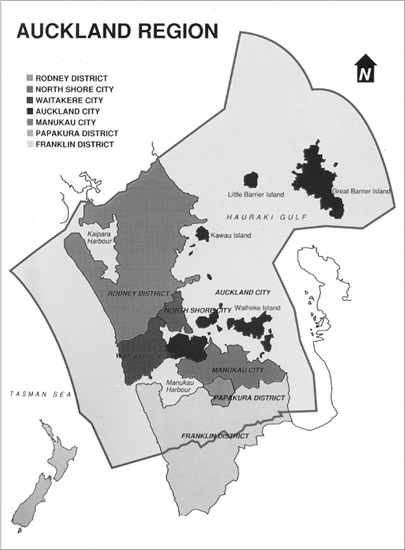

Map by courtesy of Mr Tony Garnier and the Auckland Regional Council.

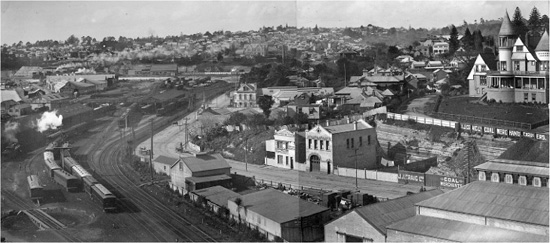

‘Beach Road and Parnell, 1906.’ The reclamations that began east of the city from 1871 on drove Campbell to abandon Logan Bank. By 1912, the year of his death, those reclamations had reached Parnell Point, on which he had built Kilbryde. AUCKLAND HARBOUR BOARD COLLECTION, NEW ZEALAND NATIONAL MARITIME MUSEUM.

Changes to the landscape of the Tamaki isthmus have been even more dramatic. David Rough, Auckland’s first harbourmaster, recalled in old age what Auckland was like before white men came. In June 1840 he rowed ashore to a landing near the foot of today’s harbour bridge, climbed a cliff and went up to the ridge we now call Ponsonby. From there he saw ‘a vast expanse of undulating country, mostly covered with fern and Manuka shrub. … But there was not a sign of cultivation nor of human habitation, the nearest native village being out of sight.’ Logan Campbell recalled a similar scene of desolation when, on 21 December 1840, he pitched his tent on the beach near the foot of today’s Queen Street. He spoke of ‘a vast sea of fern of six-feet luxuriance [that] swept away in all directions to the ridges beyond’. The ridges referred to were probably Hobson Street, Albert Park, Symonds Street and Karangahape Road.

Far-sighted though he was in his own generation, Campbell could scarcely have envisioned the growth of today’s metropolitan Auckland. In 1901, the year that he acted as mayor, the city and suburbs, admittedly on the threshold of sudden growth, had a modest population of 67,226. In 2007, the population of metropolitan Auckland has approached 1,400,000. And in 1901, although Auckland had become the largest of the four provincial cities, Wellington, Christchurch and Dunedin were each at least 60 per cent of its size, and still in a position to challenge Auckland’s numerical dominance. Over the twentieth century that comparability disappeared. In a surge of growth, particularly marked after the Second World War, Auckland has quite outstripped its sister cities, as recent returns from the Department of Statistics demonstrate. For whereas the national population has trebled over the last 60 years, that of Auckland has increased fivefold. The 2001 census revealed an ever-growing concentration of people in the northern city; 29 per cent (1,074,513) of the country’s people lived there, compared with 14 per cent (226,365) in 1936. And this concentration is projected to continue and intensify at least until 2021.

‘Hobson Bay from Point Resolution Bridge, 1931.’ Tamaki Drive completed in 1931 and the Main Trunk Railway deviation through Hobson Bay and on to Westfield led to further reclamation and construction work that brought about the demolition of Kilbryde in 1924. AUCKLAND HARBOUR BOARD COLLECTION, NEW ZEALAND NATIONAL MARITIME MUSEUM.

Numerical growth has come at a cost. During the twentieth century, Auckland merged first with the suburbs and satellite townships to fill the isthmus and then progressively engulfed extensive areas of farmland to its north and the south. Metropolitan Auckland has now emerged as an unwieldy conurbation, a cluster of towns stretching from Warkworth in the north to Pukekohe in the south. And while in Campbell’s time the city had some sort of focus in the Queen Street valley, its extensive spread since then has undermined that earlier sense of cohesion. For unlike Christchurch, or Dunedin or Nelson, Auckland can no longer comfortably claim to be a unitary city cohering around an obvious city core.

The growth of this areally extensive city has brought in its wake problems impacting on those who live there and on regional governance alike. Residents complain of costly housing and rates, and of inconvenient, time-consuming and often nightmarish travel to and from work. Keeping pace with the infrastructural needs of far-flung emerging suburbs – providing fresh water, drainage, transport and the like – has been a constant headache for local government. Especially transport. Motorway construction, public road and rail services, and provision of adequate trans-harbour transport have rarely kept up with expanding demand.

These issues call for co-ordinated action, for a ‘Greater Auckland’ solution, to use a term that was already in use 100 years ago. But how is an overarching solution possible, given the particularist spirit that prevails within the region’s ruling councils? The 1989 reorganisation of local government in the Auckland region, which forced the amalgamation of 39 municipalities and created in their stead four incorporated cities and the three territorial districts to exercise municipal authority over the 5024 square kilometres that make up the Auckland Region, clearly did not go far enough. The Auckland Regional Council, set up originally in 1974 to provide some sort of oversight of the then balkanised local jurisdictions, has, because of statutory limitations, been relegated to the sidelines to carry out lesser tasks. The result is a highly inefficient system of local government. Auckland has 264 elected representatives to run the region, twice the number of MPs who are running the whole country. It follows that the failure of the eight Auckland councils to speak with a united voice has been a great handicap in getting the requisite funding from central government for the region’s infrastructural projects.

Confusion in governance has given rise to the impression that today’s metropolitan Auckland is no more than an agglomeration of overgrown villages, self-contained, stingy about sharing expenses, prone to behave like jealous siblings within a highly disputatious family. The business consultant Tony Garnier has recorded the jibe of outsiders that modern Auckland has been transformed over the years into 100 villages, tenuously ‘linked together by spaghetti-like motorways and a coat-hanger harbour bridge!’ A journalist critic has declared that Aucklanders ‘share nothing but a phonebook’.

The history of colonial Auckland suggests that these are not intractable difficulties. Although bigger than those that confronted their nineteenth-century counterparts, the governance problems challenging today’s councils are no more complex. The infrastructural needs of the city in 1871, when the Auckland City Council and Auckland Harbour Board were first formed, are remarkably similar to those confronting Auckland today: the need for improved road and rail transport and the provision of adequate fresh water and drainage. The solution arrived at then, is probably today’s solution – a unified approach.

At bottom, modern Auckland’s disunity is more apparent than real. For the component parts of this apparently amorphous city are in fact bound together, as was nineteenth-century Auckland, by the strongest of unifying imperatives, a common economy whose continued prosperity depends on combined attempts to overcome shared otherwise intractable problems arising out of rapid growth. What is needed is a governmental structure to match that economic unity. Since the initiative is unlikely to come from the councils where vested interests are entrenched, the time has probably come for Parliament to cut the knot and create a new unitary authority for Auckland.

The unusual growth of the city’s population during the twentieth century was driven not by natural increase alone but by the inward flow of migrants. In the first half of the century this influx expressed the continuing flow of people from south to north, and from country to town – of which Maori became a significant element from 1945 onwards. These domestic trends continued in the second half of the century, but much more noticeable has been the inflow of migrants from abroad. In the immediate post-war period, immigrants from Britain and western Europe predominated. From the mid-1950s on, however, these people were joined by some thousands of migrants from the various Pacific Islands and, in the last quarter of the century, by people from a wide range of countries, but most markedly people of Asian ethnicity.

These more recent immigrants, replicating the settlement patterns of rural Maori in the early post-war period, and of Pacific Island immigrants since the 1950s, have congregated in disproportionately high numbers in Auckland, attracted initially perhaps by employment possibilities or the ‘bright lights’ of a relatively big city that has also become the main international airport of entry. Once in Auckland, many migrants tended to go no further. And, subsequently, the ‘contagion of numbers’, which is an element in chain migration, meant that later arrivals saw merit in entering existing enclaves already established by members of their own national group in the city and suburbs.

Auckland’s size and multicultural character have confirmed the opinion of people elsewhere in the country, and especially in provincial areas, that the northern city has become a place apart – too large, too impersonal and lacking in coherence. Auckland has become, so these critics say, an archetypal big city, whose self-seeking commercial spirit has led it to lose the true values of heartland New Zealand. What makes this defect the more reprehensible, according to this view, is the suspicion that the city is not pulling its weight economically, battening upon the true income-generating part of New Zealand south of the Bombay Hills, where farms, forests and tourism really sustain the national economy.

Whether Auckland is indeed faltering through having developed on too narrow an economic base is highly questionable. The same charge was laid against the city in the 1850s and 1860s. Economic historians, as a general rule, do not regard the proliferation of financial and business services as an aberration but rather as a normal phase of big city development in the post-industrial world. The rest of New Zealand, as part of a global economy, in fact needs the kind of city Auckland has become, just as much as Auckland relies on so-called heartland New Zealand in order to survive.

And yet for outsiders to regard the northern city as a place apart is no new thing. And it has certain logic. Interestingly, that that is just how Auckland struck Rudyard Kipling way back in 1896. The perception of Auckland’s exceptionalism predated Auckland’s late-twentieth-century surge in population and the big-city mentality that has issued from that. The story of Auckland in Campbell’s time serves to remind us that the city’s commercial and entrepreneurial character is no modern phenomenon but as old as the settlement itself, and indeed part of the region’s distinctive heritage. That the saying that ‘the business of Auckland is business’ has become a truism makes it none the less true. And it is nothing for Aucklanders to be ashamed of.

In the twenty-first century there is a revived interest in Auckland’s heritage. But thus far it has tended to be confined to buildings, places, walks and physical things. This interest must be widened to include a full story of Auckland in days gone by. Otherwise we become a community without a memory, a distinct possibility in a city adopted by so many incomers whose cultural roots lie elsewhere.

A wise Arabic proverb says: ‘He who has lost sight of the past has lost sight of himself’. To know one’s past is to be enrichingly aware of one’s identity. This is true for an individual, true for a family. It is no less true for a city.

To help recover that lost memory has been an objective of this book.