In the preceding chapters we have considered a small part of those earthquakes only which have occurred during the last fifty years, of which accurate and authentic descriptions happen to have been recorded. We shall next proceed to examine some of earlier date, respecting which information of geological interest has been obtained.

[The chronological account of earthquakes continues with nineteen further examples, from Java in 1772, through great disasters at Lisbon in 1755 and Conception in 1750, to Jamaica in 1692.]

* * *

We have now only enumerated the earthquakes of the last hundred and forty years, respecting which, facts illustrative of geological inquiries are on record. Even if our limits permitted, it would be a tedious and unprofitable task to examine all the obscure and ambiguous narratives of similar events of earlier epochs, although, if the localities were now examined by geologists well practised in the art of interpreting the monuments of physical changes, many events which have happened within the historical era might still be determined with precision. The reader must not imagine, that in our sketch of the occurrences in the short period above alluded to, we have given an account of all, or even the greater part of the mutations which the earth has undergone, by the agency of subterranean movements. Thus, for example, the earthquake of Aleppo, in the present century, and of Syria in the middle of the eighteenth, would doubtless have afforded numerous phenomena of great geological importance, had those catastrophes been described by scientific observers. The shocks in Syria in 1759, were protracted for three months, throughout a space of ten thousand square leagues, an area compared to which that of the Calabrian earthquake, of 1783, was insignificant. Accon, Saphat, Balbeck, Damascus, Sidon, Tripoli, and many other places, were almost entirely levelled to the ground. Many thousands of the inhabitants perished in each, and in the valley of Balbeck alone twenty thousand men are said to have been victims to the convulsion. It would be as irrelevant to our present purpose to enter into a detailed account of such calamities, as to follow the track of an invading army, to enumerate the cities burnt or rased to the ground, and reckon the number of individuals who perished by famine or the sword. If such then be the amount of ascertained changes in the last one hundred and forty years, notwithstanding the extreme deficiency of our records during that brief period, how important must we presume the physical revolutions to have been in the course of thirty or forty centuries, during which, some countries habitually convulsed by earthquakes have been peopled by civilized nations! Towns engulphed during one earthquake may, by repeated shocks, have sunk to enormous depths beneath the surface, while their ruins remain as imperishable as the hardest rocks in which they are inclosed. Buildings and cities submerged for a time beneath seas or lakes, and covered with sedimentary deposits, must, in some places, have been re-elevated to considerable heights above the level of the ocean. The signs of these events have probably been rendered visible by subsequent mutations, as by the encroachments of the sea upon the coast, by deep excavations made by torrents and rivers, by the opening of new ravines and chasms, and other effects of natural agents, so active in districts agitated by subterranean movements. If it be asked why if such wonderful monuments exist, so few have hitherto been brought to light – we reply – because they have not been searched for. In order to rescue from oblivion the memorials of former occurrences, we must know what we may reasonably expect to discover; and under what peculiar local circumstances. The inquirer, moreover, must be acquainted with the action and effects of physical causes, in order to recognise, explain, and describe, correctly, the phenomena when they present themselves.

The best known of the great volcanic regions of which we sketched the boundaries, in the eighteenth chapter, is that which includes Southern Europe, Northern Africa, and Central Asia, yet nearly the whole even of this region must be laid down in a geological map as ‘Terra Incognita.’ Even Calabria may be regarded as unexplored, as also Spain, Portugal, the Barbary states, the Ionian Isles, the Morea, Asia Minor, Cyprus, Syria, and the countries between the Caspian and Black Seas. We are, in truth, beginning to obtain some insight into one small spot of that great zone of volcanic disturbance, the district around Naples, a tract by no means remarkable for the violence of the earthquakes which have convulsed it.

If, in this part of Campania, we are enabled to establish, that considerable changes in the relative level of land and sea have taken place since the Christian era, it is all that we could have expected, and it is to recent antiquarian and geological research, not to history, that we are principally indebted for the information. We shall proceed to lay before the reader some of the results of modern investigations in the Bay of Baiæ and the adjoining coast.

Temple of Jupiter Serapis. – This celebrated monument of antiquity affords, in itself alone, unequivocal evidence, that the relative level of land and sea has changed twice at Puzzuoli, since the Christian era, and each movement both of elevation and subsidence has exceeded twenty feet. Before examining these proofs we may observe, that a geological examination of the coast of the Bay of Baiæ, both on the north and south of Puzzuoli, establishes in the most satisfactory manner an elevation at no remote period, of more than twenty feet, and the evidence of this change would have been complete even if the temple had to this day remained undiscovered. If we coast along the shore from Naples to Puzzuoli we find, on approaching the latter place, that the lofty and precipitous cliffs of indurated tuff, resembling that of which Naples is built, retire slightly from the sea, and that a low level tract of fertile land, of a very different aspect, intervenes between the present sea-beach, and what was evidently the ancient line of coast. The inland cliff is in many parts eighty feet high near Puzzuoli, and as perpendicular as if it was still undermined by the waves. At its base, the new deposit attains a height of about twenty feet above the sea, and as it consists of regular sedimentary deposits, containing marine shells, its position proves that since its formation there has been a change of more than twenty feet in the relative level of land and sea.

The sea encroaches on these new incoherent strata, and as the soil is valuable, a wall has been built for its protection; but when I visited the spot in 1828, the waves had swept away part of this rampart, and exposed to view a regular series of strata of tuff, more or less argillaceous, alternating with beds of pumice and lapilli, and containing great abundance of marine shells, of species now common on this coast, and amongst them

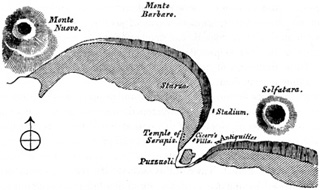

30. Ground plan of the coast of the Bay of Baiæ in the environs of Puzzuoli.

a. Remains of Cicero’s villa, N side of Puzzuoli. |

a. Antiquities on hill S.E. of Puzzuoli. |

b. Ancient cliff now inland. |

b. Ancient cliff now inland. |

c Terrace composed of recent submarine deposits |

c. Terrace composed of recent submarine deposits. |

d. Temple of Serapis. |

31. Two sections, the one exhibiting the relation of the recent marine deposits to the more ancient in the Bay of Baiæ to the north of Puzzuoli, and the other exhibiting the same relation to the south-east

Cardium rusticum, Ostrea edulis, Donax trunculus (Lam.) and others. The strata vary from about a foot to a foot and half in thickness, and one of them contains abundantly remains of works of art, tiles, squares of mosaic pavement of different colours, and small sculptured ornaments, perfectly uninjured. Intermixed with these I collected some teeth of the pig and ox. These fragments of building occur below as well as above strata containing marine shells.

If we then pass to the north of Puzzuoli and examine the coast between that town and Monte Nuovo, we find a repetition of analogous phenomena. The sloping sides of Monte Barbaro slant down within a short distance of the coast, and terminate in an inland cliff of moderate elevation, to which the geologist perceives at once, that the sea must, at some former period, have extended. Between this cliff and the sea is a low plain or terrace, called La Starza, corresponding to that before described on the south-east of the town; and, as the sea encroaches rapidly, fresh sections of the strata may readily be obtained, of which the annexed is an example.

Section on the shore north of the town of Puzzuoli.

|

Ft. | In. |

1. Vegetable soil |

1 |

0 |

2. Horizontal beds of pumice and scoriæ, with broken fragments of unrolled bricks, bones of animals, and marine shells |

1 |

6 |

3. Beds of lapilli, containing abundance of marine shells, principally Cardium rusticum, Donax trunculus Lam., Ostrea edulis, Triton cutaceum, Lam. and Buccinum serratum, Brocchi, the beds varying in thickness from one to eighteen inches |

10 |

0 |

4. Argillaceous tuff containing bricks and fragments of buildings not rounded by attrition |

1 |

6 |

The thickness of many of these beds varies greatly as we trace them along the shore, and sometimes the whole group rises to a greater height than at the point above described. The surface of the tract which they compose appears to slope gently upwards towards the base of the old cliffs. Puzzuoli itself stands chiefly on a promontory of the older tufaceous formation, which cuts off the new deposit, although I detected a small patch of the latter in a garden under the town.

Now if these appearances presented themselves on the eastern or southern coast of England, a geologist would naturally endeavour to seek an explanation in some local depression of high water-mark, in consequence of a change in the set of the tides and currents: for towns have been built, like ancient Brighton, on sandy tracts intervening between the old cliff and the sea, and in some cases they have been finally swept away by the return of the ocean. On the other hand, the inland cliff at Lowestoff, in Suffolk, remains, as we stated in the fifteenth chapter, at some distance from the shore, and the low green tract called the Ness may be compared to the low flat called La Starza, near Puzzuoli. But there are no tides in the Mediterranean; and to suppose that sea to have sunk generally from twenty to twenty-five feet since the shores of Campania were covered with sumptuous buildings, is an hypothesis obviously untenable. The observations, indeed, made during modern surveys on the moles and cothons (docks) constructed by the ancients in various ports of the Mediterranean, have proved that there has been no sensible variation of level in that sea during the last two thousand years. A very slight change would have been perceptible; and had any been ascertained to have taken place, and had it amounted only to a difference of a few feet, it would not have appeared very extraordinary, since the equilibrium of the Mediterranean is only restored by a powerful current from the Atlantic.

Thus we arrive, without the aid of the celebrated temple, at the conclusion that the recent marine deposit at Puzzuoli was upraised in modern times above the level of the sea, and that not only this change of position, but the accumulation of the modern strata, was posterior to the destruction of many edifices, of which they contain the imbedded remains. If we now examine the evidence afforded by the temple itself, it appears, from the most authentic accounts, that the three pillars now standing erect, continued, down to the middle of the last century, half buried in the new marine strata before described. The upper part of the columns, being concealed by bushes, had not attracted the notice of antiquaries; but, when the soil was removed in 1750, they were seen to form part of the remains of a splendid edifice, the pavement of which was still preserved, and upon it lay a number of columns of African breccia and of granite. The original plan of the building could be traced distinctly; it was of a quadrangular form, seventy feet in diameter, and the roof had been supported by forty-six noble columns, twenty-four of granite, and the rest of marble. The large court was surrounded by apartments, supposed to have been used as bathing-rooms; for a thermal spring, still used for medicinal purposes, issues now just behind the building, and the water, it is said, of this spring, was conveyed by marble ducts into the chambers. Many antiquaries have entered into elaborate discussions as to the deity to which this edifice was consecrated; but Signor Carelli, who has written the last able treatise on the subject, endeavours to show that all the religious edifices of Greece were of a form essentially different – that the building, therefore, could never have been a temple – that it corresponded to the public bathing-rooms at many of our watering-places, and, lastly, that if it had been a temple, it could not have been dedicated to Serapis, – the worship of the Egyptian god being strictly prohibited at the time when this edifice was in use, by the senate of Rome.

It is not for the geologist to offer an opinion on these topics, and we shall, therefore, designate this valuable relic of antiquity by its generally received name, and proceed to consider the memorials of physical changes, inscribed on the three standing columns in most legible characters by the hand of nature. (See Frontispiece.) The pillars are forty-two feet in height; their surface is smooth and uninjured to the height of about twelve feet above their pedestals. Above this, is a zone, twelve feet in height, where the marble has been pierced by a species of marine perforating bivalve – Lithodomus, Cuv. The holes of these animals are pear-shaped, the external opening being minute, and gradually increasing downwards. At the bottom of the cavities, many shells are still found, notwithstanding the great numbers that have been taken out by visitors. The perforations are so considerable in depth and size, that they manifest a long continued abode of the Lithodomi in the columns; for, as the inhabitant grows older and increases in size, it bores a larger cavity, to correspond with the increasing magnitude of its shell. We must, consequently, infer a long continued immersion of the pillars in sea-water, at a time when the lower part was covered up and protected by strata of tuff and the rubbish of buildings, the highest part at the same time projecting above the waters, and being consequently weathered, but not materially injured. On the pavement of the temple, lie some columns of marble, which are perforated in the same manner in certain parts, one, for example, to the length of eight feet, while, for the length of four feet, it is uninjured. Several of these broken columns are eaten into, not only on the exterior, but on the cross fracture, and, on some of them, other marine animals have fixed themselves. All the granite pillars are untouched by Lithodomi. The platform of the Temple is at present about one foot below high-water mark, (for there are small tides in the Bay of Naples,) and the sea, which is only one hundred feet distant, soaks through the intervening soil. The upper part of the perforations then are at least twenty-three feet above high-water mark, and it is clear, that the columns must have continued for a long time in an erect position, immersed in salt-water. After remaining for many years submerged, they must have been upraised to the height of about twenty-three feet above the level of the sea.

So far the information derived from the Temple corroborates that before obtained from the new strata in the plain of La Starza, and proves nothing more. But as the temple could not have been built originally at the bottom of the sea, it must have first sunk down below the waves, and afterwards have been elevated. Of such subsidences there are numerous independent proofs in the Bay of Baiæ. Not far from the shore, to the north-west of the Temple of Serapis, are the ruins of a Temple of Neptune, and a Temple of the Nymphs, now under water. These buildings probably participated in the movement which raised the Starza, but, either they were deeper under water than the Temple of Serapis, or they were not raised up again to so great a height. There are also two Roman roads under water in the Bay, one reaching from Puzzuoli towards the Lucrine Lake, which may still be seen, and the other near the Castle of Baiæ. The ancient mole too, which exists at the Port of Puzzuoli, and which is commonly called that of Caligula, has the water up to a considerable height of the arches; whereas Brieslak justly observes, it is next to certain, that the piers must formerly have reached the surface before the springing of the arches. A modern writer also reminds us, that these effects are not so local as some would have us believe; for on the opposite side of the Bay of Naples, on the Sorrentine coast, which, as well as Puzzuoli, is subject to earthquakes, a road, with some fragments of Roman buildings, is covered to some depth by the sea. In the island of Capri, also, which is situated some way at sea, in the opening of the Bay of Naples, one of the palaces of Tiberius is now covered with water. They who have attentively considered the effects of earthquakes before enumerated by us during the last one hundred and forty years, will not feel astonished at these signs of alternate elevation and depression of the bed of the sea and the adjoining coast during the course of eighteen centuries, but, on the contrary, they will be very much astonished if future researches fail to bring to light similar indications of change in all regions of volcanic disturbances. That buildings should have been submerged, and afterwards upheaved, without being entirely reduced to a heap of ruins, will appear no anomaly, when we recollect that in the year 1819, when the delta of the Indus sank down, the houses within the fort of Sindree subsided beneath the waves without being overthrown. In like manner, in the year 1692, the buildings around the harbour of Port Royal, in Jamaica, descended suddenly to the depth of between thirty and fifty feet under the sea without falling. Even on small portions of land, transported to a distance of a mile, down a declivity, tenements like those near Mileto, in Calabria, were carried entire. At Valparaiso, buildings were left standing when their foundations, together with a long tract of the Chilian coast, were permanently upraised to the height of several feet in 1822. It is true that, in the year 1750, when the bottom of the sea in the harbour of Penco was suddenly uplifted to the extraordinary elevation of twenty-four feet above its former level, the buildings of that town were thrown down; but we might still suppose that a great portion of them would have escaped, had the walls been supported on the exterior and interior with a deposit, like that which surrounded and filled to the height of ten or twelve feet the Temple of Serapis at Puzzuoli.

The next subject of inquiry, is the era when these remarkable changes took place in the Bay of Baiæ. It appears, that in the Atrium of the Temple of Serapis, inscriptions were found in which Septimus Severus and Marcus Aurelius record their labours in adorning it with precious marbles. We may, therefore, conclude, that it existed at least down to the third century of our era in its original position. On the other hand, we have evidence that the marine deposit forming the flat land called La Starza was still covered by the sea in the year 1530, or just eight years anterior to the tremendous explosion of Monte Nuovo. Mr. Forbes has lately pointed out the distinct testimony of an old Italian writer Loffredo, in confirmation of this important point. Writing in 1580, Loffredo declares that fifty years previously, the sea washed the base of the hills which rise from the flat land before alluded to, and at that time he expressly tells us that a person might have fished from the site of those ruins which are now called the Stadium. (See wood cut, No. 30.) Hence it follows, that the subsidence of the ground on which the Temple stood, happened at some period between the third century and the beginning of the sixteenth century. Now in this interval the only two events which are recorded in the imperfect annals of the dark ages, are the eruption of the Solfatara in 1198, and an earthquake in 1488 by which Puzzuoli was ruined. It is at least highly probable, that earthquakes, which preceded the eruption of the Solfatara, which is very near the Temple, (see wood cut, No. 30) caused a subsidence, and the pumice and other matters ejected from that volcano might have fallen in heavy showers into the sea, and would thus immediately have covered up the lower part of the columns. The action of the waves might afterwards have thrown down many pillars, and formed strata of broken fragments of the building intermixed with volcanic ejections, before the Lithodomi had time to perforate the lower part of the columns. In like manner, the sea acting on other submerged buildings, would naturally have caused a similar stratum, containing works of art and shells for several miles along the coast.

Now it is perfectly evident from Loffredo’s statement, that the re-elevation of the low tract called La Starza took place after the year 1530, and long before the year 1580; and from this alone we might confidently conclude that the change happened in the year 1538 when Monte Nuovo was formed. But fortunately we are not left in the slightest doubt that such was the date of this remarkable event. Sir William Hamilton has given us two original letters describing the eruption of 1538, the first of which by Falconi, dated 1538, contains the following passages. ‘It is now two years since there have been frequent earthquakes at Puzzuoli, Naples, and the neighbouring parts. On the day and in the night before the eruption (of Monte Nuovo), above twenty shocks great and small were felt. – The next morning (after the formation of Monte Nuovo) the poor inhabitants of Puzzuoli quitted their habitations, &c., some with their children in their arms, some with sacks full of their goods, others carrying quantities of birds of various sorts that had fallen dead at the beginning of the eruption, others again with fish which they had found, and which were to be met with in plenty on the shore, the sea having left them dry for a considerable time. – I accompanied Signor Moramaldo to behold the wonderful effects of the eruption. The sea had retired on the side of Baiæ, abandoning a considerable tract, and the shore appeared almost entirely dry from the quantity of ashes and broken pumice-stones thrown up by the eruption. I saw two springs in the newly discovered ruins, one before the house that was the Queen’s, of hot and salt-water, &c.’33 So far Falconi – the other account is by Pietro Giacomo di Toledo, which begins thus: ‘It is now two years since this province of Campagna has been afflicted with earthquakes, the country about Puzzuoli much more so than any other parts: but the 27th and the 28th of the month of September last, the earthquakes did not cease day or night in the town of Puzzuoli; that plain which lies between lake Avernus, the Monte Barbaro and the sea was raised a little, and many cracks were made in it, from some of which issued water; at the same time the sea immediately adjoining the plain dried up about two hundred paces, so that the fish were left on the sand a prey to the inhabitants of Puzzuoli. At last, on the 29th of the same month, about two o’clock in the night, the earth opened, &c.’34 Now both these accounts, written immediately after the birth of Monte Nuovo, agree in expressly stating, that the sea retired, and one mentions that its bottom was upraised. To this elevation we have already seen that Hooke, writing at the close of the seventeenth century, alludes as to a well known fact. The preposterous theories, therefore, that have been advanced in order to dispense with the elevation of the land, in the face of all this historical and physical evidence, are not entitled to a serious refutation. The flat land, when first upraised, must have been more extensive than now, for the sea encroaches somewhat rapidly, both to the north and south-east of Puzzuoli. The coast has of late years given way more than a foot in a twelve-month, and I was assured by fishermen in the bay, that it has lost ground near Puzzuoli, to the extent of thirty feet, within their memory. It is, probably, this gradual encroachment which has led many authors to imagine that the level of the sea is slowly rising in the Bay of Baiæ, an opinion by no means warranted by such circumstances. In the course of time the whole of the low land will, perhaps, be carried away, unless some earthquake shall remodify the surface of the country, before the waves reach the ancient coast-line; but the removal of this narrow tract will by no means restore the country to its former state, for the old tufaceous hills and the interstratified current of trachytic lava which has flowed from the Solfatara, must have participated in the movement of 1538; and these will remain upraised even though the sea may regain its ancient limits.

In 1828 excavations were made below the marble pavement of the Temple of Serapis, and another costly pavement of mosaic was found, at the depth of five feet or more below the other. The existence of these two pavements at different levels seems clearly to imply some subsidence previously to all the changes already alluded to, which had rendered it necessary to construct a new floor at a higher level. But to these and other circumstances bearing on the history of the Temple antecedently to the revolutions already explained, we shall not refer at present, trusting that future investigations will set them in a clearer light.

In concluding this subject, we may observe, that the interminable controversies to which the phenomena of the Bay of Baiæ gave rise, have sprung from an extreme reluctance to admit that the land rather than the sea is subject alternately to rise and fall. Had it been assumed that the level of the ocean was invariable, on the ground that no fluctuations have as yet been clearly established, and that, on the other hand, the continents are inconstant in their level, as has been demonstrated by the most unequivocal proofs again and again, from the time of Strabo to our own times, the appearances of the temple at Puzzuoli could never have been regarded as enigmatical. Even if contemporary accounts had not distinctly attested the upraising of the coast, this explanation should have been proposed in the first instance as the most natural, instead of being now adopted unwillingly when all others have failed. To the strong prejudices still existing in regard to the mobility of the land, we may attribute the rarity of such discoveries as have been recently brought to light in the Bay of Baiæ and the Bay of Conception. A false theory it is well known may render us blind to facts, which are opposed to our prepossessions, or may conceal from us their true import when we behold them. But it is time that the geologist should in some degree overcome those first and natural impressions which induced the poets of old to select the rock as the emblem of firmness – the sea as the image of inconstancy. Our modern poet, in a more philosophical spirit, saw in the latter ‘The image of Eternity,’ and has finely contrasted the fleeting existence of the successive empires which have flourished and fallen, on the borders of the ocean, with its own unchanged stability.

———Their decay

Has dried up realms to deserts: – not so thou,

Unchangeable, save to thy wild waves’ play:

Time writes no wrinkle on thine azure brow;

Such as creation’s dawn beheld, thou rollest now.

CHILDE HAROLD, Canto iv.35