7A Table of contents

* * *

Chinese Text

飲膳正要卷一(Continued)

四部叢刊續編子部:7A–15A, 16A–34B, 36B–38B, 39B–50A

7A Table of contents

8A

9A

10A

11A

12A

13A Three Sages

14A

15A

16A

17A

18A Avoidances

19A Pearls and Jade

20A Avoidances for Pregnant Women

21A Wet Nurses

22A

23A

24A Liquor

25A

26A Delicacies

27A

28A

29A

30A

31A

32A

33A

34A

35A

36A

37A

38A

39A

40A

41A

42A

43A

44A

45A

46A

47A

48A

49A

50A

* * *

Translation

[Chüan One]

[7A] Yin-shan cheng-yao Table of Contents

Chüan 1:

Record of the Three August Sages

Nurturing Life and Avoiding Things to Be Shunned

Food Avoidances during Pregnancy

Food Avoidances for a Wet Nurse

Things to Avoid and Shun When Drinking Liquor

Strange Delicacies of Combined Flavors:

Mastajhi Soup

Barley Soup

Bal-po Soup

Šaqimur Soup

Fenugreek Seed Soup

Deer Head Soup

Pine Pollen [Juice] Soup

Russian Olive [Elaeagnus angustifolia] [Fruit] Soup

Barley *Samsa Noodles

Barley Strip-Noodles

Glutinous Rice Flour *Chöp

River Pig Broth

*Achchiq [“Bitter”] Soup

Euryale Flour Swallow’s Tongue *Suyqa[sh]

Euryale Flour Blood Noodles

Euryale Flour *Jüzmä

Euryale Flour *Chöp

Euryale Flour Hun-t’un

[7B] Sundry Broth

Meat and Vegetable Broth

Pearl Noodles

Yellow Soup

Three in the Cooking Pot

Mallow Leaf [Malva sp] Broth

Long Bottle Gourd [Lagenaria siceraria var clavata] Soup

Turtle Soup

Cup Steamed

Oil Rape Shoots Broth

Bear Soup

Carp Soup

Roast Wolf Soup

*Ishkäne

*Chöppün Noodles

Black Broth Noodles

Chinese Yam Noodles

Hanging Noodles

*Jingtei Noodles

Sheep’s Skin Noodles

Tutum Ash

Fine *Salma

Water Dragon *Suyqa[sh]

*[U]mach

*Shoyla Toyym

Soup Congee

Millet Insipid Congee

*Qamh [Triticum durum] Soup

*Seu Soup

Broiled Sheep’s Heart

Broiled Sheep’s Loins

Deboned Chicken Morsels

Roasted Quail

Rabbit Plate

“Tangut” Lungs

Turmeric [-colored] Tendons

Drum *Qazi

Sheep Heads Dressed in Flowers

Fish Cakes

[8A] Cotton Rose[-Petal] Chicken

Meat Cakes

Salt Stomach

Näwälä

Turmeric [-colored] Fish

Deboned Wild Goose Morsels

Galangal Sauce Hog’s Head

Cat-tail “Sweet Melon Pickles”

Deboned Sheep’s Head Morsels

Deboned Ox Hoof Morsels

Fineq *Chizig

Liver and Sprouting [Ginger]

Horse Stomach Plate

Scalded *Jasa’a

Boiled Sheep’s Hooves

Boiled Sheep’s Breast

Fine Fish Hash

Red Strips

Roast Wild Goose

Roast Eurasian Curlew

Willow-steamed Lamb

Quick *Manta

Deer Milk Fat *Manta

Egg-plant *Manta

Quartz Horns

Butter Skin *Yubqa

Päräk Horns

*Shilön Horns

Pleurotus ortreatus [Mushroom] Pao-tzu

*Qurim Bonnets

Poppy Seed Buns

Cow’s Milk Buns

*Chuqmin

Borbi[n] Soup

Miqan-u kö[n]lesün

Chüan 2:

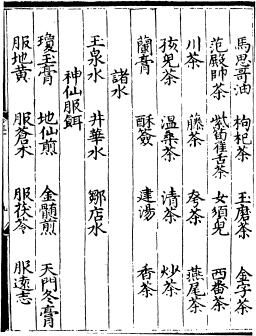

[8B] Various Hot Beverages and Concentrates:

Cassia Syrup

Cassia-Garuwood Syrup

Lichee Paste

Oriental Flowering Apricot [Prunus mume] Pellet

Red Currant Decoction

Ginseng Puree

Immortal’s Tsangshu Puree

Apricot Frost Puree

Chinese Yam Puree

Puree of Four

Ginger-Jujube Puree

Fennel Puree

Decoction for Stagnant Ch’i

Oriental Flowering Apricot Puree

Chinese Quince Puree

Detoxifying Dried Orange Peel Puree

Qatiq Cakes

Cinnamon Qatiq Cakes

Tabilqa Cakes

Fragrant Orange Spice Cakes

Cow Marrow Paste

Chinese Quince Concentrate

Hazelnut Concentrate

Purple Perilla Concentrate

Kumquat Concentrate

Cherry Concentrate

Peach Concentrate

Pomegranate Syrup

Rose Hips Concentrate

Red Currant Sharba[t]

Cicigina

Pine Seed Oil

Apricot Seed Oil

Liquid Butter

Ghee

Mäskä Oil

Chinese Matrimony Vine Fruit Tea

Jade Mortar Tea

Golden Characters Tea

[9A] Fan-tien-shuai Tea

Purple Shoots Sparrow Tongue Tea

Nu-hsü-erh Tea

Tibetan Tea

Szu-ch’uan Tea

Rattan Tea

K’ua Tea

Swallow Tail Tea

Children’s Tea

Warm Mulberry Tea

Clear Tea

Roasted Tea

Orchid Paste

*Süttiken

Fortified Broth

Aromatic Tea

Various Waters:

Spring Water

Well Splendor Water

Doses and Foods of the Beneficent Immortals:

Red Jade Paste

Earth Immortal Decoction

Golden Marrow Decoction

Chinese Asparagus Paste

Taking Chinese Foxglove

Taking Tsangshu

Taking China Root

Taking Chinese Senega

[9B] Wuchiapi Liquor

Taking Cassia

Taking Pine Nuts

Pine Knot Liquor

Taking Pagoda Tree Fruits

Taking Chinese Matrimony Vine [Leaves]

Taking Lotus Flowers

Taking Chestnuts

Taking Solomon’s Seal

The Method for the Spirit Pillow

Taking Sweetflag

Taking Sesame Seeds

Taking Schisandra

Taking Sacred Lotus Fruits

Taking Lotus Seeds

Lotus Shoots

Taking Chinese Cornbind

What is Advantageous for the Four Seasons

Overindulgence in the Five Flavors

Foods that Cure the Various Illnesses

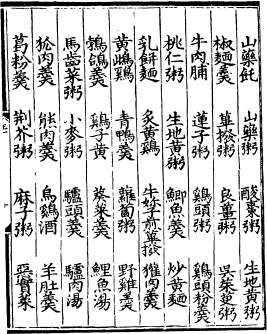

Sprouting Chinese Foxglove Chicken

Lamb Honey Paste

Sheep Entrails Gruel

Sheep’s Spine Gruel

White Sheep’s Kidney Gruel

Pig Kidney Congee

Chinese Matrimony Vine Fruit and Sheep’s Kidney Congee

Deer’s Kidney Gruel

Mutton Gruel

Deer Feet Soup

Deer Horn Liquor

Black Ox Marrow Decoction

Fox Meat Soup

Black Chicken Soup

Ghee Liquor

[10A]Chinese Yam T’o

Chinese Yam Congee

Sour Jujube Congee

Sprouting Chinese Foxglove Congee

Chinese Flower Pepper Dough Gruel

Long Pepper Congee

Lesser Galangal Congee

Evodia Fruit Congee

Beef Jerky

Lotus Seed Congee

Euryale Fruits Congee

Euryale Powder Gruel

Peach Seed Congee

Sprouting Chinese Foxglove Congee

Bream Gruel

Roasted Yellow Flour

Cheese Flour

Broiled Yellow Chicken

Cow’s Milk Decocted Long Pepper

Chinese Badger Meat Gruel

Yellow Hen

Green[-headed] Duck Gruel

Chinese Radish Congee

Pheasant Gruel

Pigeon Gruel

Egg Yolk

Carp Soup

Purslane Congee

Wheat Congee

Donkey’s Head Gruel

Donkey’s Meat Soup

Fox Meat Gruel

Bear Meat Gruel

Black Chicken Liquor

Sheep’s Stomach Gruel

Kudzu Starch Gruel

Chingchieh Congee

Hemp Seed Congee

Burdock

[10B] Black Donkey’s Skin Gruel

Sheep’s Head Hash

Wild Pig Meat Broth

Otter Liver Gruel

Bream Gruel

Food Avoidances When Taking Medicines

Benefits and Harmfulness of Foods

Foodstuffs Which Mutually Conflict

Poisons in Foodstuffs

Animal Transformations

Chüan 3:

Grain Foods:

Paddy Rice

Non-Glutinous Rice

Foxtail Millet

Millet

Green Millet

Yellow Millet

Panicled Millet

Red Panicled Millet

Chi Panicled Millet

*Qamh

Mung Beans

White Beans

Soybeans

Adzuki Beans

Chickpeas

Green Small Beans

Garden Peas

Hyacinth Beans

Wheat

Barley

Buckwheat

Sesame Seeds

“Iranian” Sesame Seeds

Malt-Sugar

Honey

Yeast

Vinegar

Sauce

Salted Bean Relish

Salt

[11A] Liquor:

Tiger Bone Liquor

Wolfthornberry Liquor

Chinese Foxglove Liquor

Pine Knot Liquor

China Root Liquor

Pine Root Liquor

Lamb Liquor

Acanthopanax Bark Liquor

Olnul “Navel” Liquor

Small Coarse Grain Liquor

Arajhi Liquor

*Sürmä Liquor

Animal Foods:

Ox

Sheep

Gazelle

The Blue Sheep

Horse

Wild Horse

Elephant

Camel

Wild Camel

Bear

Donkey

Sika Deer

Red Deer

River Deer

Dog

Pig

Wild Boar

Otter

Tiger

Leopard

Pere David’s Deer

Musk Deer

Muntjac Deer

Fox

Rhinoceros

Wolf

Hare

Wildcat1

Tarbuqa[n]

Weasel

Poultry:

[11B] Swan

Oriental Swangoose

Wild Goose

Crane

Eurasian Curlew

Chicken

Pheasant

Eared Fowl

Duck

Wild Duck

Tufted Duck2

The Mandarin Duck

Pigeon

Dove

Great Bustard

Collared Crow

Common Quail

Sparrow

Bunting

Fish:

Carp

Golden Carp

Chinese Bream

“White Fish”

“Yellow Fish”

“Green Fish”

Sheatfish

Sawfish

Mud Eel

Pao-yü

Puffer

Abarqu Fish

Qilam Fish

Softshelled Turtle

Crab

Shrimp

Sea Snail

Trough Shells

Wei

Fresh Water Mussels

The Prickly Sculpin

Fruits:

Peach

Chinese Pear

Persimmon

Chinese Quince

Flowering Apricot

Japanese Plum

Prinsepia

Pomegranate

Crab Apple

Apricot

Mandarin Orange

Tangerine

Sweet Orange

Chestnut

Jujube

Cherry

Grapes

Walnut

[12A] Pine Nut

Lotus Seed

Euryale ferox Fruit

Trapa bispinosa Fruit

Lichee

Longan

Ginkgo Nut

Chinese Myrica Fruit

Hazelnut

Torreya Nut

Cane Sugar

Sweet Melon

Watermelon

Sour Jujube

Flowering Apricot Red

Citron

Acorns

P’ing-p’o

Badam Nut

Pistä

Vegetables:

Mallow

Swiss Chard

Chinese Parsley

Mustard Greens

Chinese Onions

Garlic

Chinese Chives

Winter Melon

Cucumbers

Chinese Radish

Carrot

T’ien-ching Vegetable

Long Bottle Gourd

Oriental Pickling Melon

Pear-Shaped Bottle Gourd

*Möög Mushroom

Chün-tzu [Fungi]

Tree Ears

Bamboo Shoots

Cattail Shoots

Sacred Lotus Rhizome

Chinese Yam

Lettuce

[12B] Bokchoy

P’eng-hao

Chinese Eggplant

Amaranth Greens

Oil Rape

Spinach

White Sugar Beet

Basil

Smartweed

Purslane

Pleurotus ortreatus [Mushroom]

Shallot

Chinese Artichoke

Elm Seeds

Shajhimur

Chugundur

Lily Root

Seaweed

Bracken

Vetch

Sonchus spp greens

Water-celery

Spices:

Black Pepper

Chinese Flower Pepper

Lesser Galangal

Fennel

Liquorice3

Coriander

Dried Ginger

Sprouting Ginger

Zhira

Mandarin Orange Peel

Cassia

Turmeric

Pippali

Grain-of-paradise

Cubebs

Schisandra Fruits

Fenugreek Seeds

Red Yeast

Poppy Seeds

Mastajhi

Za’faran

Kasni

Anjudan (same as Angwa)

Safflower

Chih-tzu

Cattail [Pollen]

“Muslim” Green

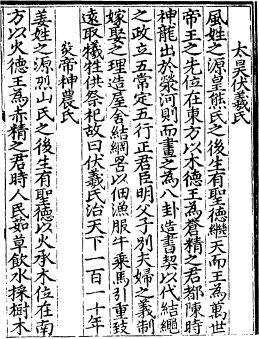

[13A] Vast Heaven Fu-Hsi

He was first of the surname Feng and was the descendant of Huang-hsiung. He had sagely virtue at birth. He succeeded to Heaven and became ruler. He was the first of the emperors and kings of ten thousand generations. His position was in the east and he ruled by virtue of wood. He was the lord of the Green Essence. He made his capital at Ch’en-shih. The beneficent spirit dragon appeared at Yung-ho. When this happened, Fu-hsi marked down its [design] to make the eight diagrams. He created writing and incisings on bamboo and wood to replace the method of knotted cords. He established the five cardinal relationships, and determined the five transitional phases. He defined lord and minister, clarified father and son, separated the duties of man and wife, and ordered marriage. He invented housing. He plaited together nets and snares to hunt and fish. He hitched up oxen and rode on horses to move heavy goods and attain distances. He selected sacrificial victims to supply rites and sacrifices. Therefore it is said that Fu Hsi ruled the empire well for one hundred ten years.

The Brilliant Emperor Shen-Nung

He was the first of the surname Ch’iang and was the descendent of Liehshan. He had sagely virtue at birth. He received wood with fire. His position was in the south and he ruled by virtue of fire. He was lord of the Red Essence. People of his time ate herbs and drank water, and collected the fruits of trees. [13B] They also ate the meat of the lo-mang [“naked mang”4] and many developed illnesses. Shen-nung thereupon sought things they could eat. He sampled the hundred herbs and planted the five grains to support the people. Markets were held during the day. Shen-nung invented potting and the casting of metal. He made axes and fashioned digging tools and taught the people to till and sow grain. Therefore it is said: Shen-nung made his capital in Ch’ü-fu and ruled the empire well for 120 years.

The Yellow Emperor Hsien-Yüan

He was the first of the surname Chi. He was the son of Shao-tien-tzu, the lord of Hsiung Kuo. He was born beneficent and numinous, grew up to great intelligence and when mature attained to Heaven. He ruled by virtue of earth. He was the lord of the Yellow Essence. Therefore it is said: the Yellow Emperor made his capital at Cho-lu and received the “River Map.” After he had observed the configurations of sun, moon, stars, and planets there were first books on astrology. He ordered Great Yao to probe the natures of the five transitional phases. He inquired by oracle about that which the Dipper establishes. He originated the cycle of 60 and ordered Yung Ch’eng to create the calendar. He ordered Li Shou to create mathematics. He ordered Ling Lun to make the 12 standard pitch pipes. He ordered Ch’i Po to set medical recipes. He made clothing to express differences of social position. He put the weapons of war into order. He made boats and chariots and divided cultivated area from wasteland. He ruled the empire well for 100 years.

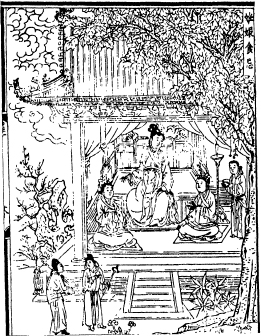

[14A] [Uncaptioned illustration]

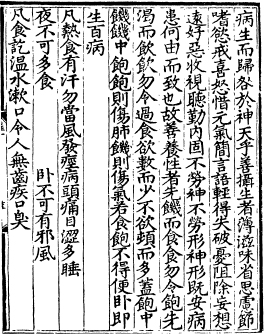

[14B] Nurturing Life and Avoiding Things to Be Shunned5

Those of the very ancients who knew the Way had methods based in yin-yang, and kept in harmony with magical calculations. They practiced moderation in their drinking and eating, and there was a regimen to their activity and repose. They were not disorderly in their actions. Therefore they could attain to a great age. People of today are not like that at all. There is no regimen in their activity and repose. They do not know how to avoid things which should be shunned in their drinking and eating, and also are not careful about moderation. They are much addicted to lust. They like strongly-flavored food; cannot keep the mean; and do not know how to be satiated. Therefore most, I think, will be decrepit at fifty. The way of peace and joy resides in nourishing. For the Way of nourishing, nothing is better than keeping the mean. Where there is keeping to the mean, then there will be no excess and illnesses which do not respond to treatment. Spring, autumn, winter, and summer are the yin-yang of the four seasons. Falling ill is due to excess, that is, not according with the character of the seasons, and overdoing it. Thus those who would nurture life are without the defect of excess and waste. They can also preserve their true natures. How can they be harmed through being targeted by external miasmas? Thus being good at nourishing is better than taking medicines. But it is better to take medicines if one is not good at nourishing. If there are those in the world who are not good at nourishing, and are also not good at taking medicines, they will suddenly [15A] fall ill. And will they not assign the blame to beneficent Heaven? Those who are good at protecting their lives; prefer lightly-flavored food; spare their minds; moderate their desires; limit their emotions; are frugal of their primordial ch’i, laconic in their speech, even-tempered about gain and loss. They make a clean breast of anxiety; eliminate wild fantasy; keep away from likes and dislikes; accumulate personal experience. They insist on inner steadfastness. They do not weary the spirit and do not weary the form. If spirit and form are at peace, where can illness come from? Thus those who are good at nurturing their natures, are hungry before eating. When they eat they do not eat to satiation. They are thirsty before drinking, and do not drink to excess. In eating there should be frequent meals of small intake. There should not be a few set meals with eating to excess, lest one experience hunger amidst satiation or satiation amidst hunger. If one eats to satiation it wounds the lungs. If one is hungry it wounds the ch’i. If one eats to satiation one will not sleep well. The hundred illnesses then arise.

Whenever hot food is served there will be sweating. One should stay out of the wind. It will produce convulsions, headache, eye astringency,6 and excessive drowsiness.

One should not eat much at night.

When sleeping one should not be [exposed to] evil wind.7

Whenever you finish eating, rinse the mouth with warm water. This will cause a person to be without tooth disease and bad breath.

[15B] One should not fan the body when sweating. It will produce a hemiplegia.

One must not defecate or urinate towards the northwest.8

One must not hold back a bowel movement or urine. It will cause a person to develop knee impairment caused by overstrain, and chill numbness pain.9

One must not defecate or urinate towards stars or planets, the sun or the moon, temples for spirits or ancestral halls.

If traveling by night, one must not sing or call out loudly.

A daily avoidance: one should not eat to satiation in the evening.

A monthly avoidance: one must not become greatly tipsy on the last day of the month.

An annual avoidance: one must not go on a long trip in the evening.

A lifetime avoidance: one must not have sexual intercourse in a brightly lit room.

It is better to sleep alone for a single night than take drugs for a thousand mornings.

On one’s own birthday, or on the birthdays of one’s parents, do not eat the meat of animals associated with these days.10

Whenever a person is sitting, he must certainly sit still and formally. It will rectify the heart.

Whenever a person is standing, he must certainly stand up straight. This will straighten the body.

If one should stand, one should not stand for long periods. Standing wounds the bones.

If one sits, one should not sit for long periods. Sitting wounds the blood.

[16A] If one walks, one should not walk for long periods. Walking harms the sinews.

If one lies down, one should not lie down for long periods. Lying down wounds the ch’i.

If one looks at something, one should not look for long periods. It harms the spirit.

If one has eaten to satiation, one must not wash the head. [It will cause a person] to contract “wind diseases.”

If one is afflicted with “red eye disease [conjunctivitis],” one should practice complete sexual abstinence. If not, it will cause a person to develop an internal screen [an internal oculopathy].

If one bathes, one must stay out of the wind. The hundred apertures of the pores will all be open. One must absolutely avoid the easy entry of evil wind.

One should not ascend to a high place with insecure footing, ride fast in a chariot or on a horse. The ch’i will be thrown into disarray, and the spirit will be frightened. The souls will fly away and be lost.

If there is a great wind, great rain, great cold or great heat, one cannot go and come in an unseemly manner.

The mouth must not blow on the flame of a lamp. It will harm the ch’i.

Whenever the daylight is dazzling, one must not stare fixedly. It harms the eyes.

One must not stare off into the distance as far as the eye can see. It harms the power of the eye.

In sitting or lying down one must not be exposed to the wind, or in a damp place.

One must not sleep at night in bright light. The souls will not protect [the body].

One must not doze during the daytime. It harms the primordial ch’i.

One must not talk when eating, and one must go to bed without conversation. One should fear wounding the ch’i.

Whenever one encounters a temple or shrine, one must not abruptly enter.

[16B] Whenever one encounters wind and rain, thunder and lightning, it is obligatory to shut the gate, sit up straight, and light incense. One should fear the various spirits passing by.

If one is angry, one must not become violently angry. Anger produces ch’i illnesses and malignant boils.

It is better to spit short distances than long distances. It is better not to spit at all than spitting short distances.

Skins of tiger and leopard should not be put close to a meat rack. It harms the eye.

Avoiding lust is like avoiding an arrow. Avoiding dissipation is like avoiding an enemy. No one should drink tea on an empty stomach. Eat little congee after the shen hour [3:00–5:00 PM].

There was an ancient person who said: “He who has entered the wilderness, cannot have an empty stomach in the morning, and cannot be full in the evening.” Not only those who have entered the wilderness, all of us should avoid an empty stomach whenever it is early.

There was an ancient person who said: “Cook noodles until soft. Cook meat until tender. Drink little liquor. Sleep alone.”

The ancients practiced hygiene and nourished [themselves] in their ordinary daily activity and repose. People of the present wait until old age to protect life. This effort is without benefit.

Whenever one lies down at night, if one rubs the two hands together to make them warm, and massages the eyes, one will continue to be without ocular disease.

[17A] Whenever one lies down at night, if one rubs the two hands together to make them warm, and rubs the face, then ch’uang-kan11 will not develop.

In one expelling of the breath one should rub the hands together ten times. During each rubbing of the hands, there should be ten manipulations. If one continues this for a long time, wrinkles will be few and one’s color extremely good.

Every morning, bathe the eyes with hot water. One will normally be without eye disease.

Brushing the teeth at night is better than brushing the teeth in the morning. Tooth disease will not arise.

If one brushes the teeth with salt every morning, one will normally be without tooth disease.12

If the hair is combed one hundred times whenever one goes to bed, one will normally have very little “head wind [recurrent headache].”

Whenever ones goes to bed at night, if one goes to bed after washing the feet, the four extremities will be without chill-type diseases.

When the extremely hot weather arrives, one should not wash the face with cold water. It produces eye disease.13

One should not sit for a long time in any place there is withered wood, which is below a large tree and which has long been shaded and damp. It is to be feared that the yin-ch’i [of the place] will touch a person.

One should not bathe during the days at the beginning of autumn. It causes one’s skin to rough and dry. Po-hsieh [apparently seborrheic dermatitis] is produced as a result.

[17B] If one is as a rule silent, the primordial ch’i will not be wounded.

If one has few cares, quick-witted understanding will shine.

Do not be angry. The hundred spirits [i.e., one’s own intellectual capacities] will be peaceful and pleasant.

Do not be vexed. The place of the heart will be pure and cool.

Joy should not be excessive. Desire should not be given free reign.

[18A] [Illustration Caption] Food Avoidances During Pregnancy

[18B] [Illustration Caption] During Pregnancy it is Beneficial to see Carp and Peacocks.

[19A] [Illustration Caption] During Pregnancy it is Beneficial to see Pearls and Jade.

[19B] [Illustration Caption] During Pregnancy it is Beneficial to see a Flying Wild Goose and a Running Dog.

[Instructing Children in the Womb]

[20A] Sages of high antiquity had a method for instructing children in the womb. Women of ancient times did not sleep on their sides when pregnant with a child; did not sit on the side; and did not stand to the side. They did not eat evil flavors. If meat was not cut straight they did not eat it. If a mat was not straight, they did not sit on it. Their eyes did not see depraved colors [i.e., lustful sights]; their ears did not hear lewd sounds. And at night they had blind musicians intone the Poetry and discuss orthodox things. As a result of their doing this, I dare say that they gave birth to children whose appearance was correct and whose talents were superior. Thus T’ai-jen gave birth to Wen-wang. He was intelligent and had sagely wisdom. He could hear one thing and know a hundred. These were all abilities learned in the womb. Sages are born very much influenced [by what happens before birth]. Pregnant women therefore avoid funerals and mourning, ravaged bodies, and persons crippled by disease or exhausted by poverty. It is suitable for them to see worthy and good things, joyful and happy things, pleasant and beautiful things. If one wants a child with great knowledge, one should view carp and peacocks. If one wants a child who will be pleasant and beautiful, one should view precious pearls and beautiful jade. If one wants a child who will be brave and strong, one should view flying wild geese and racing dogs. If even good or bad things like this influence [children in the womb], how much more will this be the case if one does not know avoidances in drinking and eating?

[20B] Things to Avoid During Pregnancy

If the mother has eaten hare meat, it will cause the child to be mute and have a hare-lip.

If the mother has eaten goat meat, if will cause the child to be ill frequently.

If the mother has eaten eggs and dried fish, it will cause the child to have many sores.

If the mother has eaten mulberry fruits and duck eggs, it will cause the child to be a breech birth.

If the mother has eaten sparrow meat and has drunk liquor, it will cause the child to have lust in his heart, and to be dissolute without any sense of shame.

If the mother has eaten chicken and glutinous rice, it will cause the child to produce tapeworms.

If the mother has eaten sparrow meat and bean sauce, it will cause the child to develop an extremely dark discoloring of the face.

If the mother has eaten turtle meat, it will cause the child to have a short neck.

If the mother has eaten donkey meat, it will cause the child to be late.

If the mother has eaten any thick frozen fluids, it will cause a miscarriage.

If the mother eats mule meat, if will make for a difficult birth.14

[21A] [Illustration Caption] Avoidances for a Wet Nurse:

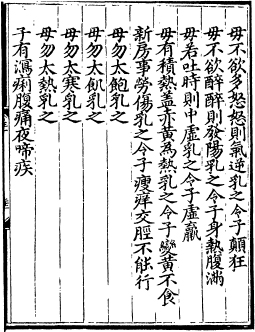

[21B] Avoidances for a Wet Nurse

Food Avoidances for a Wet Nurse

Whenever one has produced children, one should choose among various mothers. One must seek for one who is strong and without illness; who is compassionate and well-meaning; whose character is liberal and generous; who is warm and good, careful and polished; and who is of few words, and make her wet nurse. The child needs the milk of the wet nurse for nourishment. This is also food that can be drunk by grown-ups. Good and evil are from their respective practice; how can milk food not be in accord with the nature of the wet nurse? Whether or not a child has, or has not an illness, depends upon the caution in diet of the wet nurse. If she does not know avoidances in her drinking and eating; if she is not cautious in her actions; if she is covetous of whatever immediate thing tastes good; if she forgets the body and does not control her nature, it will result in illness and cause the child to contract it as well. This is a matter of the wet nurse causing the child to contact disease, I think.

Various Avoidances for a Wet Nurse

A wet nurse must not nurse during the heat of summer. [If this is the case] the child will be inclined towards yang, and will vomit a great deal.

A wet nurse must not nurse during the cold of winter. [If this is the case] the child will be inclined towards yin, and will cough and have diarrhea a lot.

[22A] A wet nurse should not wish to be very angry. When she is angry the ch’i is contrary. If she nurses, the child will become wild.

A wet nurse should not wish to be tipsy. When one is tipsy the yang is issued forth. If she nurses, the child’s body will become hot and the bowels full.

If a wet nurse should ever spit, then the center will [suffer from] deficiency. If she nurses, this will cause the child to suffer from deficiency emaciation.

If a wet nurse has retained heat, and if there are red [or] yellow [skin] fever symptoms, and she nurses, the child will become jaundiced and will not eat.

If the wet nurse is exhausted and wounded from recent intercourse, and she nurses, the child will be thin and sickly. Its shins will cross, and the child unable to walk.

A wet nurse must not nurse a child after eating to over-satiation.

A wet nurse must not nurse a child when she is extremely hungry.

A wet nurse should not nurse a child when the weather is extremely cold.

A wet nurse should not nurse a child when the weather is extremely hot.

If a child has leaking [heat] diarrhea, abdominal pain or morbid nocturnal crying illness [22B] the wet nurse should avoid eating foods that make cold or cool and give rise to illness.

If the child has retained heat, infantile convulsions, or sores and ulcers, the wet nurse should avoid eating foods that make damp and hot and move wind.

If the child has an illness with scabies or ringworm sores, the wet nurse should avoid eating fish, shrimp, chicken, and horse meat foods which give rise to sores.

If the child has severe constipation, infantile malnutrition15 or emaciation disease, the wet nurse should avoid eating fresh eggplant, cucumber, etc.

[23A] When a Woman Has Just Given Birth:

Before the child has cried, take the juice of soaked golden thread [rhizome of Coptis chinensis], mix evenly with a little cinnabar, and smear a little inside the child’s mouth. It gets rid of womb heat and evil ch’i, and will make sores and pustules extremely few.

When a Woman Has Just Given Birth:

Take chingchieh [herb or flower of Schizonepeta tenuifolia] and golden thread [rhizome] boiled in water. Add a Uttle gall bladder juice from a male wild boar and wash the child. Afterwards, although he will develop malignant boils of macule, they will be very uncommon until the end of the child’s life.

When a Child Has Sores and Eruptions at Birth:

Take the head of a hare of the 12th. lunar month, along with the fur and bones, and decoct together in the same water. Wash the child. It removes heat and gets rid of poison, and can prevent the various sores of macule from developing. Although they may develop, it will happen very rarely.

Whenever a Child Has Contracted Macule at Birth:

[23B] Have the child drink the milk of a small black mother donkey. When it grows up, the child will not develop the various poisons of sores and eruptions. If they do appear, they will be very few in number. This will likewise cure a small child’s heart of heat and wind convulsions.16

[24A] [Illustration Caption] Things to Avoid and Shun When Drinking Liquor

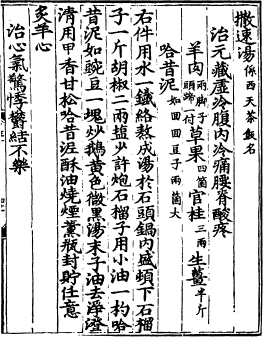

[24B] Things to Avoid and Shun When Drinking Liquor:

The flavor of liquor is bitter, sweet-acrid. It is greatly heating and has poison. It is good for putting into effect the powers of medicines. It destroys the hundred evil factors, removes evil ch’i, puts through blood and pulse, fills bowels and stomach, moistens muscle, eliminates care and melancholy. It is best to drink little. If one drinks much, it wounds the spirit and shortens life. It changes a person’s basic nature. Its poison is extreme. If one drinks and gets tipsy excessively, this is the origin of destruction of life.

If one drinks liquor, it is undesirable to allow oneself to over drink. If one realizes that one has drunk too much, it is best to spit it out quickly. If not, it results in phlegm disease.

If one becomes tipsy, one should not become helplessly, excessively intoxicated. If so, to the end of one’s life, one will not be able to eliminate the hundred illnesses.

One cannot drink liquor for an extended period of time. One should be afraid of corrupting bowels and stomach, of soaking the marrow, and steaming the sinew.

If one is tipsy one should not sleep facing the wind. It can produce wind diseases.

If one is tipsy one cannot sleep facing the sun. It will cause a person to go mad.

If one is tipsy one cannot have a person fan one. It will produce a hemiplegia.

If one is tipsy one cannot sleep exposed. It will produce chill numbness.

If one sweats while exposed to the wind when tipsy, it gives rise to leaking wind.17

If one is tipsy one cannot sleep [on] millet stalks. It produces leprosy.

[25A] If one is tipsy one cannot eat voraciously, or become rebuking or angry. It produces boils.

If one is tipsy one cannot ride on a horse. When the horse jumps it wounds sinew and bone.

If one is tipsy one cannot engage in sexual intercourse. If it is a minor intercourse, it produces black facial discolorings [and] coughing. If it is a major intercourse, it wounds the viscera, and [produces] bloody stool and perianal abscesses.

If one is tipsy one cannot wash the face with chilled water. It produces sores.

If one is tipsy and sobering up, one cannot get drink again. This is damage on top of damage.

If one is tipsy one cannot call loudly, or be extremely angry. It causes one to produce ch’i.

One must not become extremely tipsy on the last day of the moon. One should avoid the emptiness of the moon.

If one is tipsy one cannot drink fermented milks. They create throat stoppage illness [dysphagia].

If one is tipsy one should not lie down casually. The face will produce furuncles. Internally, abdominal mass will be produced.

When one is greatly tipsy one must not shout with lamps lit. It is to be feared that the souls will fly away, and will not guard the body.

If one is tipsy one cannot drink thick frozen fluids. One loses the voice. It forms cadaverous throat stoppage.

If one drinks liquor, and the liquor is thick so that one’s reflection does not appear in it, do not drink it.

[25B] If one is tipsy one cannot retain urine. It will result in dysuria, knee joint impairment caused by overstrain, and chill numbness.

If one drinks liquor on an empty stomach, one will vomit when tipsy.

If one is tinsy one cannot retain excrement. It will produce dysentery perianal abscesses.

Various sweet things are liquor avoidances.

If one is tipsy with liquor, one cannot eat pork. It produces “wind.”

If one is tipsy, one cannot strongly exert oneself. It wounds sinew and damages strength.

When one is drinking liquor, one can absolutely not eat pig or sheep brain. It greatly damages a person. For a gentlemen practicing physiological alchemy, the avoidance is all the greater.

If one is tipsy with liquor, one cannot expose the feet to be cooled by the wind. It often produces [evil] foot ch’i [beriberi].

One cannot sleep in a damp place when tipsy. It wounds sinew and bone. It produces chill numbness pain.

If one is tipsy one cannot bathe. It often produces eye disease.

In the case of a person who has contracted eye disease, getting tipsy from liquor and eating garlic is a strong avoidance.

[26A] [Illustration Caption] Strange Delicacies of Combined Flavors

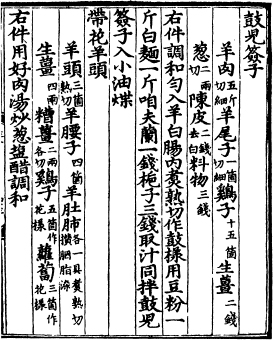

[26B] Strange Delicacies of Combined Flavors

[1.] Mastajhi [Mastic] Soup18

It supplements and increases, warms the center, and accords ch’i.

Mutton (leg; bone and cut up), tsaoko cardamoms (five), cinnamon (2 ch’ien), chickpeas [“Muslim beans”] (one-half sheng; pulverize and remove the skins).

Boil ingredients together to make a soup. Strain broth.19 [Cut up meat and put aside.] Add 2 ho of cooked chickpeas, 1 sheng of aromatic non-glutinous rice,20 1 ch’ien of mastajhi. Evenly adjust flavors with a little salt. Add [the] cut-up meat and [garnish with] coriander leaves.

[2.] Barley21 Soup

It warms the center and brings down ch’i. It strengthens spleen and stomach, controls polydipsia, and destroys chill ch’i. It gets rid of abdominal distension.

[27A] Mutton (leg; bone and cut up), tsaoko cardamoms (five), hulled barley (two sheng; scour wash in boiling water; parboil the grains.)

Boil ingredients to make a soup. Strain [broth. Cut up meat and put aside]. Add [the] hulled barley and boil until cooked. Evenly adjust flavors with a little salt. Add [the] cut-up meat.

[3.] Bal-po Soup (This is the name of a Western Indian food)22

It supplements the center, and brings down ch’i. It extends the diaphragm.

Mutton (leg; bone and cut up), tsaoko cardamoms (five), chickpeas (half a sheng; pulverize and remove the skins), Chinese radish.

Boil ingredients together to make a soup. Strain [broth. Cut up meat and Chinese radish and put aside]. Add to the soup [the] mutton cut up into sashuq [coin]-sized pieces, [the] cooked Chinese radish cut up into sashuq-sized pieces, 1 ch’ien of za’faran [saffron], 2 ch’ien of Turmeric, 2 ch’ien of Black [“Iranian”] Pepper [27B], half a ch’ien of kasni, [asafoetida], coriander leaves. Evenly adjust flavors with a little salt. Eat over cooked aromatic non-glutinous rice. Add a little Vinegar.

[4.] Šaqimur [Rape Turnip] Soup23

It supplements the center, and brings down ch’i. It harmonizes spleen and stomach.

Mutton (leg; bone and cut up), tsaoko cardamoms (five), chickpeas (half a sheng, pulverize and remove the skins), šaqimur (five); like Man-ch’ing [silver beet or Swiss chard]).

Boil ingredients together and make a soup. Strain [broth. Cut up meat and šaqimur and put aside]. Add 2 ho of cooked chickpeas, 1 sheng of aromatic non-glutinous rice, [the] cooked šaqimur beet cut up into sashuq-sized pieces. Add [the] cut-up meat. Evenly adjust flavors with a little salt.

[5.]Fenugreek Seed24 Soup

[28A] It supplements lower primordial energy, orders loin and knee, warms the center, and accords ch’i.

Mutton (leg; bone and cut up), tsaoko cardamoms (five), fenugreek seeds (1 liang; a kind of hulba[t] [i.e., Fenugreek Seeds]).

Boil ingredients together and make a soup. Strain [broth]. Add Tangut Um Ash, or “Rice Heart Suyqa[sh],” half a ch’ien of kasni. Adjust flavors with a little salt.

[6.] Chinese Quince Soup25

It supplements the center, and accords ch’i. It cures pain of loin and knee, and [evil] foot ch’i insensitivity.

Mutton (leg; bone and cut up), tsaoko cardamoms (five), chickpeas (half a sheng; pulverize and remove the skins).

Boil ingredients together into a soup. Strain [broth. Cut up meat and put aside]. Add 1 sheng of aromatic non-glutinous rice, 2 ho of cooked chickpeas, “meat pellets”, two chin of Chinese quince (take the juice), 4 liang of granulated sugar. Adjust flavors with a little salt. [28B] [The] cut-up meat can perhaps be added.

[7.] Deer Head Soup26

It supplements and increases, controls polydipsia, and cures ache of foot and knee.

Deer’s head [and] hooves (one set; remove hair and clean; bone and divide into pieces).

For the ingredients, take a large chunk of kasni, grind up into a mush and apply evenly to deer head, [and] hoof meat. Fry both the [marinated] head and hoof meat in 4 liang of vegetable oil [“Muslim lesser oil”]. Quench roasted head and hoof meat in boiling water,27 boil until soft. Add 3 ch’ien of black pepper, 2 ch’ien of kasni, 1 ch’ien of long pepper [Piper longum], 1 cup of cow’s milk, 1 ho of juice of sprouting ginger. Adjust flavors with a little salt.

[Variation:] In one method, use deer’s tail to obtain broth. Add ground ginger. Adjust flavors with salt.

[8.] Pine Pollen [Juice] Soup28

It supplements the center, and increases ch’i. It strengthens sinew and bone.

[29A] Mutton (leg; bone and cut up), tsaoko cardamoms (five), chickpeas (half a sheng; pulverize and remove the skins).

Boil ingredients together into a soup. Strain [broth]. Fry together: one cooked sheep’s thorax (cut up into sashuq-sized pieces), 2 ho of pine pollen juice, half a ho of juice of sprouting ginger. [Add to soup and] evenly adjust flavors with onions, salt, vinegar and [garnish with] coriander leaves. Eat with Long Rolled Bread.

[9.] Russian Olive [Fruit] Soup29

It supplements the center, and increases ch’i. It strengthens spleen and stomach.

Mutton (leg; bone and cut up), tsaoko cardamoms (five), chickpeas (half a sheng; remove the skins).

Boil ingredients together into a soup. Strain [broth]. Add together to the pot: a cooked dried sheep’s thorax (sliced up), 3 sheng of Russian olive fruits, Chinese cabbage or nettle leaf. Evenly adjust flavors with salt.

[10.] [29B] Barley *Samsa Noodles30

They supplement the center, and increase ch’i. They strengthen spleen and stomach.

Mutton (leg; bone and cut up), tsaoko cardamoms (five), chickpeas (half a sheng; remove the skins).

Boil ingredients together into a soup. Strain [broth. Set aside meat]. Make [*samsa] noodles from a combination of 3 chin of barley flour, 1 chin of bean paste. [Fill with] mutton and fry. Adjust flavors with a fine qima, 2 ho of juice of sprouting ginger, coriander leaves, salt, and vinegar.

[11.] Barley Strip-Noodles31

They supplement the center, increase ch’i, and strengthen spleen and stomach.

Mutton (leg; bone and cut up), tsaoko Cardamoms (five), lesser galangal [Alpinia officinarum].

Boil ingredients together into a soup. Strain [broth. Set meat aside.] Add sheep’s liver sauce ([decoct and] take the bouillon), and 5 ch’ien of black pepper. Cut [the] cooked mutton into [small, thin pieces like] armor scales, cut up 2 liang of pickled ginger and [add along with] 1 liang of sweet melon [Cucumis melo] pickles cut-up like “armor scales.”

[30A] Adjust flavors with salt and vinegar. A thick broth can also be used.

[12.] Glutinous Rice Flour *Chöp32

They supplement the center, and increase ch’i.

Mutton (leg; bone and cut up), tsaoko cardamoms (five), lesser galangal (two ch’ien).

Boil ingredients together into a soup. Strain [broth. Set aside meat]. Use sheep’s liver sauce (decoct and take the bouillon). Add 5 ch’ien of black pepper. Combine two chin of glutinous rice flour, and one chin of bean paste and make the *chöp. Cut up [the] mutton into a fine qima and add [as stuffing]. [Put into soup and] adjust flavors with salt and vinegar. A thick broth can also be used.

[13.] River Pig Broth33

It supplements the center, and increases ch’i.

Mutton (leg; bone and cut up), tsaoko cardamoms (five).

[30B] Boil ingredients together into a soup. Strain [broth. Set meat aside]. Take [the] mutton (cut up finely into qima), five ch’ien of mandarin orange peel (remove the white),34 2 liang of White Onions (cut up finely), two ch’ien of spices, salt, and [sheep’s liver] sauce, and make the stuffing. Use 3 chin of white flour to make the skins. Make the “River Pigs.” Cook by frying in vegetable oil [“lesser oil”] and when done put into the soup. Adjust flavors with salt. Bouillon can perhaps also be used.

[14.] *Achchiq [“Bitter”] Soup

It supplements the center, and increases ch’i.

Mutton (leg; bone and cut up), tsaoko cardamoms (five), lesser galangal (two ch’ien).

Boil ingredients together into a soup. Strain [broth. Set meat aside]. Add sheep’s liver sauce. Decoct bouillon from broth and sauce. Add 5 ch’ien of black pepper. In addition, cut up [the] mutton into strips. Cut up into “armor scales” one sheep’s tail, one sheep’s tongue, one set of sheep kidneys and add together with two liang of *möög [mushrooms], and Chinese cabbage. Adjust flavors with broth, salt and vinegar.

[15.] Euryale Flour Swallow’s Tongue * Suyqa[sh]35

[31A] They supplement the center, and increase vital energy.

Mutton (leg; bone and cut up), tsaoko cardamoms (five), chickpeas (half a sheng; pulverize and remove the skins).

Boil ingredients together into a soup. Strain [broth. Set meat aside]. Use two chin of euryale flour, 1 chin of bean paste, work together and cut into *suyqa[sh]. Use [the] mutton cut up into a fine qima [and] one ho of juice of sprouting ginger [as stuffing. Stuff *suyqash] and fry. [Add to soup and] adjust flavors with onions.

[16.] Euryale Flour Blood Noodles36

They supplement the center, and increase the vital air.

Mutton (leg; bone and cut up), tsaoko cardamoms (five), chickpeas (half a sheng; pulverize, remove the skins).

Boil ingredients together into a soup. Strain [broth. Set meat aside]. Use two chin of euryale flour, one chin of bean paste, and sheep’s blood [31B] and combine to make *chöp. [Use] mutton cut into a fine qima [as stuffing. Stuff *chöp and] Fry. [Add to soup and] adjust flavors of everything together with onions and vinegar.

[17.] Euryale Flour *Jüzmä

They supplement the center, and increase the vital air.

Mutton (leg; bone and cut up), tsaoko cardamoms (five), chickpeas (half a sheng; pulverize and remove the skins).

Boil ingredients together into a soup. Strain [broth. Set meat aside]. Use two chin of euryale flour, one chin of bean paste, one chin of white [wheat] flour to make the noodles. Cut [the] mutton into strip qima, stuff noodles and fry. [Add to soup and] adjust flavors of everything together with onions and vinegar.

[18.] Euryale Flour *Chöp

They supplement the center, and increase the vital air.

Mutton (leg; bone and cut up), tsaoko cardamoms (five), lesser galangal (two ch’ien).

[32A] Boil ingredients together into a soup. Strain [broth. Set meat aside]. Use sheep’s liver sauce. Take the bouillon of the combined soup and sauce. Add one liang of black pepper. Then use two chin of euryale flour, one chin bean paste and make into *chöp, [stuff with the] mutton cut up into a fine qima and add. Adjust flavors with salt and vinegar.

[19.] Euryale Flour Hun-t’un37

They supplement the center, and increase ch’i.

Mutton (leg, bone and cut up), tsaoko cardamoms (five), chickpeas (half a sheng; pulverize and remove the skins).

Boil ingredients together into a soup. Strain [broth. Set meat aside]. Cut [the] mutton into stuffing. Add 1 ch’ien of salted mandarin orange peel (remove the white), 1 ch’ien of sprouting ginger (cut up finely). Spice evenly with the “five spices.” Then use two chin of the euryale flour, and one chin of bean paste, make into “Fluffy-pillow Hun-t’un” and put into the soup. Fry together a sheng of aromatic non-glutinous rice, two ho of cooked chickpeas, [32B] two ho of juice of sprouting ginger, one ho of quince juice. [Add to soup and] evenly adjust flavors with onions and salt.

[20.] Sundry Broth38

It supplements the center, and increases ch’i.

Mutton (leg, bone39 and cut up), tsaoko cardamoms (five), chickpeas (half a sheng; pulverized. Remove the skins).

Boil ingredients together into a soup. Strain [broth]. Cook together: two sheep’s heads (clean), two sets each of sheep stomachs and lungs, one set of white blood, paired sheep intestines.40 When done cut up [and add to soup]. Then use three chin of bean flour to make noodles, Stuff with half a chin of *möög [mushrooms], half a chin of apricot kernel41 paste, one liang of black pepper. Fry [with] mint42 and coriander leaves. Adjust flavors with onions, salt, and vinegar

[21.] Meat and Vegetable Broth43

[33A] It supplements the center, and increases ch’i.

Mutton (leg; bone and cut up), tsaoko cardamoms (five), chickpeas (half a sheng; pulverized. Remove the skins).

Boil ingredients together into a soup. Strain [broth. Set meat aside]. [Use] three chin of bean flour to make “strip-noodles.” Cut select mutton into long qima. Cut up: one chin of Chinese yams, two lumps of pickled ginger, one sweet melon pickle, one cheese,44 ten carrots [“Iranian radishes”], half a sheng of *möög [mushrooms], and four liang of sprouting ginger, ten eggs fried into an omelet and sliced. Use one chin of sesame seed paste and half a chin of apricot kernel paste and fry [everything together]. [Add to soup and] adjust flavors with onions, salt, and vinegar.

[22.] Pearl Noodles45

They supplement the center, and increase ch’i.

Mutton (leg; bone and cut up), tsaoko cardamoms (five), [33B] chickpeas (half a sheng; pulverized. Remove the skins).

Boil ingredients together into a soup. Strain [broth. Set aside meat]. Cut mutton into qima. Cut up each of the following: one sheep’s heart, one sheep’s liver, a set of sheep’s lungs, two liang of sprouting ginger, four liang of pickled ginger, one liang of sweet melon pickles, ten carrots, one chin of Chinese yams, one cheese, ten eggs fried into an omelet. Then fry everything together using one chin of sesame paste. [Add everything to soup and] adjust flavors with onions, salt, and vinegar.

[23.] Yellow Soup46

It supplements the center, and increases ch’i.

Mutton (leg; bone and cut up), tsaoko cardamoms (five), chickpeas (half a sheng; pulverized. Remove the skins).

Boil ingredients together into a soup. Strain [broth]. Add two ho of cooked chickpeas, one sheng of aromatic non-glutinous rice [34A], and five carrots (cut up). Use “meat pellets” [made from] the “meat pill” of the rear hoof of a sheep, one [sheep’s] rib (cut up into small, square pieces), three ch’ien of turmeric, five ch’ien of ground ginger, one ch’ien of za’faran, and coriander leaves. Adjust flavors with salt and vinegar.

[24.] Three in the Cooking Pot

It supplements the center, and increases ch’i.

Mutton (leg; bone and cut up), tsaoko cardamoms (five), lesser galangal (two ch’ien).

Boil ingredients together into a soup. Strain [broth]. Use “meat pellets” [made from] the “meat pill” of the rear hoof of a sheep, “nail-headed *suyqa[sh],” “mutton *jis-kebabi food” and one liang black pepper. Adjust flavors with salt and vinegar.

[25.] Mallow Leaf Broth47

It [Mallow Leaf] accords ch’i. It treats retained urine that does not pass. Its nature is cold and one cannot eat a lot. In the present case we have cooked the mallow leaf with various things [34B] intended to make its nature slightly warming.

Mutton (leg; bone and cut up), tsaoko cardamoms (five), lesser galangal (two ch’ien).

Boil ingredients together into a soup. [Use as stuffing] one set each of cooked sheep’s stomach and lungs (cut up), half a chin of *möög [mushrooms] (cut up). Combine five ch’ien of black pepper and one chin of white flour to make “chicken-claw vermicelli.” Add to soup. Fry mallow leaf [and add]. Adjust flavors with onions, salt, and vinegar.

[26.] Long Bottle Gourd [Lagenaria siceraria var. clavata] Soup48

It [the long bottle gourd] is cooling by nature. It is good for diabetes. It benefits the water paths.

Mutton (leg; bone and cut up), tsaoko cardamoms (five).

Boil ingredients together into a soup. Strain [broth. Set aside meat]. Use six long bottle gourds (remove the pericarps and skins, dice), [the] cooked mutton (cut into strips). Make fine vermicelli from half a ho of juice of sprouting ginger and two liang of white flour. Fry everything together. [Add to soup and] adjust flavors with onions, salt, and vinegar.

[27.] [35A] Turtle Soup49

It is good for a wounded center, and increases ch’i. It supplements [in cases of] insufficiency.

Mutton (leg; bone and cut up), tsaoko cardamoms (five).

Boil ingredients together into a soup. Strain [broth]. Cook five or six turtles. When done, remove the skin and bones, and cut into lumps [and add to soup]. Use two liang of flour to make fine vermicelli. Roast together with one ho of juice of sprouting ginger, one liang of black pepper. [Add to soup and] adjust flavors with onions, salt, and vinegar.

[28.] Cup Steamed50

It supplements the center, and increases ch’i.

Sheep’s back skin from which the hair has been removed, or mutton (three legs; bone and cut up), tsaoko cardamoms (five), lesser galangal (two ch’ien), prepared mandarin orange peel (two ch’ien; remove the white), Chinese flower pepper [“lesser pepper;” Zanthoxylum sp]51 (two ch’ien).

[35B] [Take] ingredients and fry52 together with one chin of almond paste, two ho of pine pollen [juice], and two ho of juice of sprouting ginger. Adjust flavors evenly with onions, salt and spices [five spices]. Put into a liquor cup and steam until tender. When cooked eat with long rolled bread.

[29.] Oil Rape Shoots Broth53

It supplements the center, and increases ch’i.

Mutton (leg; bone and cut up), tsaoko cardamoms (five), lesser galangal (two ch’ien).

Boil ingredients together into a soup. Strain [broth]. Use sheep’s liver, make into a sauce. [Decoct and] take the bouillon. Make noodles with five chin of bean paste [and add to soup]. Cut up finely and add: one cheese, one chin of Chinese yams, ten carrots, one sheep’s tail, mutton. Adjust flavors with oil rape [sprouts], Chinese chives,54 one liang of black pepper, salt, and, vinegar.

[30.] Bear Soup55

It treats migratory arthralgia insensitivity and [evil] foot ch’i.

[36A] Bear meat (two legs; cook. When done cut into chunks), tsaoko cardamoms (three)

[Boil] ingredients [together into a soup]. Use three ch’ien of black pepper, one ch’ien of kasni, two ch’ien of turmeric, two ch’ien of grain-of-paradise [seed of Amomum villosum or A. xanthioides], one ch’ien of za’faran. Adjust flavors of everything together with onions, salt, and sauce.

[31.] Carp Soup56

It treats jaundice, stops thirst, and pacifies the womb. If a person is ill with chronic abdominal mass he should not eat it.

Large young carp (ten; remove the scales and intestines; clean), finely ground Chinese flower pepper (five ch’ien).

Marinate ingredients with a combination of five ch’ien of ground coriander, two liang of onions (cut up), a little liquor, salt. Put fish into bouillon. Then add five ch’ien of finely ground black pepper, three ch’ien of sprouting ginger, and three ch’ien of ground long pepper. Adjust flavors with salt and vinegar.57

[32.] Roast Wolf Soup58

[36B] Ancient pen-ts’ao do not include entries on wolf meat. At present we state that its nature is heating. It treats asthenia. I have never heard that it is poisonous for those eating it. In the case of the present recipe we use spices to help its flavor. It warms59 the five internal organs, and warms the center.

Wolf meat (leg; bone and cut up), tsaoko cardamoms (three), black pepper (five ch’ien), kasni (one ch’ien), long pepper (two ch’ien), grain-of-paradise (two ch’ien), turmeric (two ch’ien), za’faran (one ch’ien).

Boil ingredients together into a soup. Adjust flavors of everything using onions, sauce, salt, and vinegar.

[33.] *Ishkäne60

It supplements and increases [for] the five internal organs.

Mutton (leg; cook. When done cut up finely), sheep’s tail (two; [cook]. When done cut up finely). Cut into long strips: sacred lotus rhizome (two), cattail rhizome [Typha sp] (two chin), cucumbers (five), sprouting ginger (half a chin), [37A] cheeses (two), pickled ginger (four liang), sweet melon pickles (half a chin), eggs (ten. Fry into an omelet), *möög [mushrooms] (one chin), Swiss chard, Chinese chives.

Use a “good meat soup” and blend together ingredients. Fry [i.e., cook dry] with two chin of sesame paste, and half a chin of finely ground ginger. Adjust flavors with onions, salt and vinegar. Eat with “Iranian buns.”

[34.] *Chöppün Noodles61

They supplement the center, and increase ch’i.

White flour (six chin; cut into fine vermicelli), mutton (two legs; cook. When done, cut into strip qima [and stuff vermicelli]), one set each of sheep intestines and lungs (Cook. When done cut up.), eggs (five; fry into an omelet. Cut into “streamers”), sprouting ginger (four liang), root and tuber of the Chinese chive62 (half a chin), *möög [mushrooms] (four liang), oil rape leaf, smartweed shoots, safflower.

[37B] Use bouillon for the ingredients. Add one liang of black pepper, Adjust flavors with salt and vinegar.

[35.] Black Broth Noodles63

They supplement the center, and increase ch’i.

White flour (cut fine vermicelli), sheep’s thorax (two; pluck and clean; cook. When done cut into sashuq-sized chunks).

Use three ch’ien of “red flour”64 to marinate ingredients. Boil until tender. Put everything together into bouillon. Add one liang of black pepper, salt and vinegar. Flavor [evenly].

[36.] Chinese Yam Noodles

They supplement [for] deficiency emaciation. They increase primordial energy.

White flour (six chin), eggs (ten; take the white), juice of sprouting ginger (two ho), bean paste (four liang).

Use three chin of Chinese yams. Cook. When done grind up into a paste and combined with ingredients to make noodles. Cut up two legs of mutton into [38A] “nail-headed qima” [as stuffing]. Use a “good meat broth,” add [noodles] and fry. Adjust flavors with onions and salt.

[37.] Hanging Noodles65

They supplement the center, and increase ch’i.

Mutton (leg; cut up into a fine qima), hanging noodles (six chin), *möög [mushrooms] (half a chin; wash; cut up.), eggs (five; fry), pickled ginger (one liang; cut up), sweet melon pickles (one liang; cut up).

Use bouillon for ingredients. Add one liang of black pepper. Adjust flavors with salt and vinegar.

[38.] *Jingtei Noodles66

They supplement the center, and increase ch’i.

Mutton (leg; roast the meat. [Make] *quruq [dried] qima),67 *möög [mushrooms] (half a chin; wash and cut up).

Use bouillon for ingredients. Add one liang of black pepper. Adjust flavors with salt and vinegar.

[39.] [38B] Sheep’s Skin Noodles

They supplement the center, and increase ch’i.

Sheep’s skins (two; remove the hair; clean; cook until tender), sheep’s tongues (two; cook.), sheep’s loins (four; cook. Cut up each [i.e., previous ingredients] like “armor scales”), *möög [mushrooms] (one chin; cleaned), pickled ginger (four liang. Cut up each like “armor scales”).

Use a good rich meat soup, or bouillon for the ingredients. Add one liang of black pepper. Adjust flavors with salt.

[40.] Tutum Ash (This is a kind of kneaded noodle)68

They supplement the center, and increase ch’i.

White flour (six chin. Make into tutum ash), mutton (leg. Roast the meat. [Make into] *quruq qima [and stuff tutum ash]).

Use a Good Meat Soup for ingredients. Add the noodles and roast [cook dry]. Adjust flavors evenly with onions. Add garlic, cream [or yogurt],69 finely ground basil.

[41.] Fine *Salma (same as “Thin Silk Border” *Salma)70

[39A] They supplement the center, and increase ch’i.

White flour (six chirr, make *salma), mutton (two legs; roast the meat. [Make into] *quruq qima [and stuff *salma]), chicken (one; cook and cut up finely), *möög [mushrooms] (half a chin; wash; cut up).

Use bouillon for ingredients. Add one liang of black pepper. Adjust flavors with salt and vinegar.

[42.] Water Dragon *Suyqa[sh]

They supplement the center, and increase ch’i.

Mutton (two legs; cook; cut up into qima), white flour (six chin. [Make dough and] cut into “cash eye *suyaa[sh]”71), [stuff *suyqash with qima], eggs (ten), Chinese yams (one chin), pickled ginger (four liang), carrots (five), sweet melon pickles (two liang. Cut up each finely), “Three Color Meat Patties.” (The inside color is of a meat patty. The outer two colors are noodle and chicken patties.)

Use bouillon for ingredients. Add two liang of black pepper. Adjust flavors with salt and vinegar.

[43.] [39B] [U]mach (a kind of hand twisted noodle. It can be glutinous rice flour or euryale flour.)

It supplements the center, and increases ch’i.

White flour (six chin; make [u]mach), mutton (two legs; cook. Cut into qima [and stuff [u]mach]).

Use a good meat soup for ingredients and roast [cook dry]. Adjust flavors of everything together with onions, vinegar, and salt.

[44.] *Shoyla Toyym (Name of an Uighur Food)

It supplements the center, and increases ch’i.

White flour (six chin; knead; make into coin shapes), mutton (two legs; cook; cut up), sheep’s tongues (two; cook; cut up), Chinese yams (one chin), *möög [mushrooms] (half a chin), carrots (five), pickled ginger (four liang; cut up).

Use a good rich meat soup, add all ingredients and roast [cook dry]. Adjust flavors with onions and vinegar.

[45.] [40A] Qima Congee72

It supplements spleen and stomach, and increases the power of ch’i.

Mutton (leg; bone and cut up. Boil into a soup. Strain [broth. Set meat aside]), millet grains (two sheng; scour and wash. [Add to soup]).

[Prepare] ingredients, use select mutton. Cut up into a chunk qima. First take [millet] grains and add to the soup. Then add the qima, rice, onions, and salt. Boil to make the congee. One can perhaps add polished rice, che-mi [uniform washed grains of fine millet], or dried rice. All are possible.

[46.] Soup Congee

It supplements spleen and stomach, and increases kidney ch’i.

Mutton (leg; bone and cut up).

Boil ingredient into a soup. Strain. Then add two sheng of millet grains to make a congee. When the congee is cooked, add rice, onions and salt. One can perhaps add polished rice, che-mi or dried rice. All are possible.

[47.] [40B] Millet Insipid Congee

It supplements the center, and increases ch’i.

Millet grains (two sheng).

[For the ingredient] first boil water, settling out impurities and straining. Then scour clean the millet, three to five times. Boil to make a congee. One can perhaps add polished rice, che-mi or dried rice. All are possible.

[48.] *Qamh [Triticum durum] Soup73

It supplements the center, and increases ch’i.

Mutton (leg; bone and cut up), *qamh (two sheng).

Boil ingredients into a soup. Strain [broth. Cut up meat into qima.] Add the *qamh (scoured clean). Then add fine qima, rice, onions and salt. Boil together into a congee. It is also possible not to use qima.

[49.] [41A] *Seu [Pomegranate] Soup (This is the name of a West Indian Food)74

It treats deficiency chill of the primordial storehouse, chill pain of the abdomen, and aching pain along the spinal column.

Mutton (two legs, the head, and a set of hooves), tsaoko cardamoms (four), cinnamon (three liang), sprouting ginger (half a chin), kasni (big as two chickpeas)

Boil ingredients into a soup using one *telir of water. Pour into a stone top cooking pot. Add a chin of pomegranate fruits, two liang of black pepper, and a little salt. The pomegranate fruits should be baked using one cup of vegetable oil and a lump of asafoetida the size of a garden pea. Roast [i.e., cook dry ingredients] until a fine yellow in color, slightly black. Remove debris and oil in the soup. Strain clean. Use the smoke produced from roasting chia-hsiang [operculum of Turbo cornutus and related spp], Chinese spikenard [Nardostachys chinensis], kasni, and butter to fumigate a jar.75 Seal up and store [the Seu Soup] as desired.

[50.] Broiled Sheep’s Heart76

It treats heart energy agitation, and depressed melancholy.

[41B] Sheep’s heart (one, including major veins), za’faran (three ch’ien).

[For] ingredients use one shallow cup of attar of roses. Dissolve [the za’faran] and take the juice. Add a little salt. Spit the sheep’s heart on a spit and broil over the fire. Baste regularly with the [attar-]za’faran juice. Continue until the basting juice is gone. If one eats this it pacifies heart ch’i. It makes a person very happy.77

[51.] Broiled Sheep’s Loins

They treat lumbago due to strain and ocular ache.

Sheep’s loins (one pair), za’faran.

[For] ingredients use one shallow cup of attar of roses. Dissolve [the za’faran] and take the juice. Add a little salt. Spit the sheep’s loins on spits and broil over the fire. Baste regularly with the [attar-]za’faran juice. Continue until the basting juice is gone. If eaten it will have great efficacy.

[52.] [42A] Deboned Chicken Morsels78

Fat chickens (ten; pluck; clean; cook and cut up. Debone as morsels), juice of sprouting ginger (one ho), onions (two liang; cut up), finely ground ginger (half a chin), finely ground Chinese flower pepper (four liang), [wheat] flour (two liang; make into vermicelli).

[For] the ingredients take the broth used to boil the chickens and fry [cook dry]. Add onions and vinegar. Adjust flavors with juice of sprouting ginger.

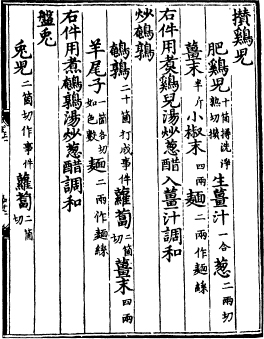

[53.] Roasted Quail79

Quail (20; cut up into pieces), Chinese radishes (two; cut up), finely ground ginger (four liang), sheep’s tail (one; cut into sashuq-sized pieces), flour (two liang; make vermicelli).

[For] ingredients take the broth used to cook the quail and fry [cook dry]. Adjust flavors with onions and vinegar.

[54.] Plate Rabbit

Ingredients: Rabbit (two; cut up into pieces), Chinese radishes (two cut up), [42B] sheep’s tail (one; cut into strips), fine spices (two ch’ien).

[For] ingredients use [sesame oil?] and fry.80 Adjust flavors with onions and vinegar. Add two liang of vermicelli. Adjust flavors.

[55.] “Tangut” Lungs81

Sheep’s lung (one), leeks (six chin; take the juice), flour (two chin; make into paste), butter (half a chin), black pepper (two liang), juice of sprouting ginger (two ho).

[For] ingredients use salt and adjust flavors evenly. Submerge the lungs in water and cook. When done baste with the juice and eat.

[56.] Turmeric[-Colored] Tendon82

Sheep’s tendon (one; cook.), sheep ribs (two; cut into long chunks), bean paste (one chin), white flour (one chin), za’faran (two ch’ien), gardenia nuts [Gardenia jasminoides] (five ch’ien).

[For] ingredients use salt and spices and adjust flavors. Dip tendon [and sheep rib chunks] in batter [i.e., made from the bean paste, white flour, za’faran and gardenia nuts]. Put into vegetable oil and fry.

[57.] [43A] Drum *Qazi83

Mutton (five chin; finely cut), sheep’s tail (one; finely cut), eggs (15), sprouting ginger (two ch’ien), onions (two liang; cut up), prepared mandarin orange peel (two ch’ien.; remove the white), spices (three ch’ien).

Flavor ingredients evenly. Put into a sheep’s white bowel and cook. When done cut up into drum shapes. Use one chin of bean paste, one chin of white flour, one ch’ien of za’faran, three ch’ien of gardenia nuts. Take the juice, and apply together to the drum *qazi. Put into vegetable oil and fry.

[58.] Sheep’s Heads Dressed in Flowers84

Sheep’s heads (three. When cooked, cut up), sheep’s loins (four), sheep’s stomach and lungs (one set of each; cook. When done, cut up. Debone as morsels. Dye with safflower), sprouting ginger (four liang), pickled ginger (two liang; cut up each), eggs (five; cut into flower shapes), Chinese radishes (three; cut into flower shapes).

[For] ingredients use a good meat soup and fry. Adjust flavors with onions, salt, and vinegar.

[59.] [43B] Fish Cakes85

Large carp (10; remove the skin, bones, head, and tail), sheep’s tail (two; mince together into a paste), sprouting ginger (one liang; cut up finely), onions (two liang; cut up finely), finely ground prepared mandarin orange peel (three ch’ien), finely ground black pepper (one liang), kasni (two ch’ien),

[To the] ingredients [other than the carp] add salt. Add to the fish and work meat. Roll into cakes like crossbow bullets. Fry in vegetable oil.

[60.] Cotton Rose-[Petal] Chicken86

Chickens (10. When cooked, debone as morsels), sheep’s stomach and lungs (each one set; cook; cut up), sprouting ginger (four liang; cut up), carrots (10; cut up), eggs (20; fry into omelets. Cut into flower shapes), spinach [true spinach, Spinacia oleracea]87 and coriander (a garnish), safflower [and] gardenia nuts (dyes), apricot kernel paste (one chin).

[For] ingredients use a good meat soup and roast. Adjust flavors with onions and vinegar.

[61.] Meat Cakes88

[44A] Select mutton (10 chin; remove the fat, membrane, and sinew. Mash into a paste), kasni (three ch’ien), black pepper (two liang), long pepper (one liang), finely ground coriander (one liang).

[For] ingredients use salt. Adjust flavors evenly. Use the fingers to make “cakes.” Put into vegetable oil and fry.

[62.] Salt Stomach89

Sheep’s bitter bowel (Wash clean with water).

Apply salt to ingredient. When it has dried in the wind, put into vegetable oil and fry.

[63.] Näwälä90

Cooked sheep’s thoraxes (two; cut into thin strips), eggs (20; cooked).

[For] ingredients use all kinds of fresh vegetables. Roll up together in bread.

[64.] Turmeric[-Colored] Fish91

[44B] Carp (10; remove the skin and scales), white flour (two chin), bean paste (one chin), finely ground coriander (two liang).

[For the] ingredients, after making a marinate using salt and spices, marinate fish and fry in vegetable oil. When done, use two liang of sprouting ginger (cut into strips), coriander leaves, safflower dye, radish slices, and fry. Adjust flavors with onions.

[65.] Deboned Wild Goose Morsels92

Wild geese (five; cook. When done cut up. Debone as morsels), finely ground ginger (half a chin).

[For] ingredients use a good meat soup and roast. Adjust flavors with onions and salt.

[66.] Galangal Sauce Hog’s Head93

Hog’s head (two; wash; cut up into chunks), prepared mandarin orange peel (two ch’ien; remove the white), lesser galangal (two ch’ien), Chinese flower pepper (two ch’ien), cinnamon (two ch’ien), tsaoko cardamom (five), vegetable oil (one chin), honey (half a chin).

Boil ingredients together until done. Then add finely ground mustard and roast. Adjust flavors with onions, vinegar and salt.

[67.] [45A] Cattail “Sweet Melon Pickles”94

Cleaned mutton (10 chin; cook. When done cut up to look like sweet melon pickles), Chinese flower pepper (one liang), cattail [rhizome] (half a chin).

[For] ingredients use one liang of fine spices. Apply evenly with salt.

[68.] Deboned Sheep’s Head Morsels95

Sheep’s head (five; cook. When done debone as morsels), finely ground ginger (four liang), black pepper (one liang).

[For] ingredients use a “good meat soup” and roast. Adjust flavors with onions, salt and vinegar.

[69.] Deboned Ox Hoof Morsels (Horse’s Hoof, Bear’s Paw are entirely the same)

Ox hooves (one set; cook. When done debone as morsels.), finely ground ginger (two liang).

[For] ingredients use a good meat soup and roast. Adjust flavors with onions and salt.

[45B] Mutton (leg; cook. When done cut up finely), Chinese radish (two; cook; cut up finely), sheep’s tail (one; cook; cut up), ka’fur [Camphor] (two ch’ien).

[For] ingredients use a good meat soup and roast. Adjust flavors with onions.

[71.] Liver and Sprouting [Ginger]

Sheep’s liver (one; drench in water; cut into fine strips), sprouting ginger (four liang; cut into fine strips), Chinese radish (two liang; cut into fine strips), basil, smartweed (each two liang; cut up into fine strips).

[For] ingredients use salt. Adjust flavors with vinegar and finely ground mustard.

[72.] Horse Stomach Plate96

Horse stomach and intestines (one set; cook. When done cut up.), finely ground mustard (half a chin).

[For] ingredients, take the white blood irrigating bowel and cut into flower shapes. [Take] the astringent spleen,97 combine with fat [i.e., suet] and mince as filling. [46A] When made into morsels, fry. Adjust flavors with onions, salt, vinegar, and finely ground mustard.

[73.] Scalded *Jasa’a (a delicacy)

*Jasa’a (two; unload; make each into a knot), kasni (one ch’ien), onions (one liang; cut up finely).

[For] ingredient use salt and work together with everything else. Fry quickly [scald] in vegetable oil. When done, then use two ch’ien of za’faran dissolved in water. Add spices. Sprinkle with finely ground coriander.

[74.] Boiled Sheep’s Hooves

Ingredients: Sheep’s hooves (five hooves; remove the hair and wash; cook until tender; cut up into chunks), finely ground ginger (one liang), spices (five ch’ien).

[To] ingredient add vermicelli and fry. Adjust flavors with onions, vinegar, and salt.

[75.] Boiled Sheep’s Breast

Sheep’s breasts (two; remove the hair and wash. Cook until tender. Cut up into sashuq-sized pieces), finely ground ginger (two liang), spices (five ch’ien).

[46B] [For] ingredient use a good meat soup. Add flour vermicelli and fry. Adjust flavors with onions and vinegar.

[76.] Fine Fish Hash98

Young carp (five; remove the skins, bones, head, and tail), sprouting ginger (two liang), Chinese radishes (two), onions (one liang), basil and smartweed (cut each into fine strips; mix with safflower).

[To] ingredients add finely ground mustard and fry. Adjust flavors with onions, salt and vinegar.

[77.] Red Strips99

Sheep’s blood combined with white flour (Cook according to recipe), sprouting ginger (four liang), Chinese radish (one), basil and smart-weed (each one liang; cut up into fine strips).

[For] ingredients use salt. Adjust flavors with vinegar and finely ground mustard.

[78.] Roast Wild Goose (Roast Cormorant and Roast Duck are the same)100

[47A] Wild goose (one; remove the feathers, bowels, and stomach and clean.), sheep’s stomach [and attached skin] (one; remove the hair; clean and use to wrap up the wild goose), onions (two liang), finely ground coriander (one liang).

Use salt and flavor ingredients together [with the onions and ground coriander]. Put into the goose’s stomach [put goose into sheep’s stomach] and roast.

[79.] Roast Eurasian Curlew

Eurasian curlews (10; pluck; clean), finely ground coriander (one liang), onions (ten stalks), spices (five ch’ien).

Apply [coriander, onions and spices] uniformly [to] ingredients and roast. One may dress the curlews in a thick flour and steam-roast until done in a cage; this is also possible. One may dress the curlews with liquid butter combined with flour, and brazier cook in a brazier; this is also possible.

[80.] Willow-Steamed Lamb101

A sheep (one; with hair).

[For] ingredient construct a brazier on the ground three ch’ih deep. Surround with stones. Heat the stones until red hot. Use a *tabaq to hold the lamb. On top use willow [branches] to cover and seal with earth. Cook until done.

[81.] [47B] Quick *Manta102

Mutton, mutton fat, onions, sprouting ginger, prepared mandarin orange peel (cut up each finely).

[To] ingredients add spices, salt and sauce, and combine into stuffing.

[82.] Deer Milk Fat103 *Manta (One can [also] perhaps make “Quick *Manta,” or perhaps “Thin-skin *Manta,” Both are possible.)

[Dried] deer milk fat, sheep’s tail (cut up each into slices like finger nails), sprouting ginger, prepared mandarin orange peel. (Cut up each finely.)

[To] ingredients add spices, and salt, and combine to make stuffing.

[83.] Eggplant *Manta104

Mutton, sheep’s fat, sheep’s tail, onions, prepared mandarin orange peel (cut up each finely), “tender” eggplant (remove the pith).

[For] combine ingredients with meats into a stuffing. But [instead of making a dough covering] put it inside the eggplant [skin] and steam. Add garlic, cream [or yogurt etc.], finely ground basil. Eat.

[84.] Cut Flowers *Manta105

[48A] Mutton, sheep’s fat, sheep’s tail, onions, prepared mandarin orange peel. (Cut up each finely.)

[To] ingredients add, according to recipe, spices, salt and sauce. Make the stuffing. Form the *Manta. Use scissors to cut out into various flower shapes. Steam. Use safflower to dye the flowers.

[85.] Quartz Horns

Mutton, sheep’s fat, sheep’s tail, onions, prepared mandarin orange peel, sprouting ginger. (Cut up each finely.)

[To] ingredients add fine spices, salt and sauce and mix [everything] together uniformly. Use bean paste to make skins. Make the horns.

[86.] Butter Skin *Yubqa

Mutton, sheep’s fat, sheep’s tail, onions, prepared mandarin orange peel, sprouting ginger. (Cut up each finely. One can perhaps add jha’uqasu[n]. This is a kind of lily root.)

[To] ingredients add spices, salt, and sauce and mix [everything] together uniformly. Use vegetable oil, rice flour and [white wheat] flour, combine to make the skins.

[87.] Päräk Horns

[48B] Mutton, sheep’s fat, sheep’s tail, young leeks. (Cut up each finely).

[To] ingredients add spices, salt, and sauce and mix [everything] together uniformly. Use white flour to make the skins. Bake on a flat iron. When done, then use liquid butter and honey. Perhaps one can use pear-shaped bottle gourd meat to make stuffing. This is also possible.

[88.] *Shilön Horns

Mutton, sheep’s fat, sheep’s tail, onions, prepared mandarin orange peel, sprouting ginger. (Cut each up finely).

[To] ingredients add spices, salt and sauce and mix [everything] together uniformly. Take white flour, honey and vegetable oil and mix together. Put into boiling water in a cauldron. When cooked make skins.

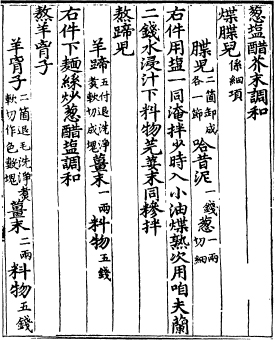

[89.] Pleurotus ortreatus [Mushroom] Pao-tzu (Some make them from crab spawn. This is also possible. Wisteria Pao-tzu is entirely the same.)

Mutton, sheep’s fat, sheep’s tail, onions, prepared mandarin orange peel, sprouting ginger. (Cut up each finely), Pleurotus ortreatus [mushrooms] (Scald in boiling water. When cooked, clean and cut up finely.)

[49A] [To] ingredients add spices, salt, sauce and make stuffing. [Use] white flour to make a thin skin. Steam.

[90.] *Qurim “Bonnets” [i.e., boqtas]106