1

The Pre-Trek Adventures of Gene Roddenberry

Late in life, Gene Roddenberry purposefully conflated his identity with that of his most famous creation. “I am Star Trek,” he often said. This was true enough for the series’ famously ardent fans, and Roddenberry reaped significant rewards from the association. Even though he lost control of the Trek movie franchise after its first entry and became a mere figurehead on Star Trek: The Next Generation after its first few seasons, Paramount Pictures continued to pay Roddenberry as a consultant because it knew fans would reject any Trek missing the franchise creator’s seal of approval. Nevertheless, defining Roddenberry by Star Trek grossly oversimplifies the man himself. He was a complex and sometimes contradictory figure who can’t be summed up in any single title.

Bob Justman came closer than anyone else to capturing the expansive Roddenberry. During Star Trek’s first season, associate producer Justman wrote a production memo that jokingly referred to his boss as “the Great Bird of the Galaxy.” Roddenberry liked the poetic nickname, and in later years Trek fans adopted it as a term of affection for the creator of their beloved franchise. Some went even further, referring to him as “Goddenberry.” Although far from divine, Roddenberry was everything else his worshipful fans imagined him to be—a highly intelligent, restlessly creative dynamo whose vision of a utopian future free from war, poverty, and discrimination continues to inspire millions. But he was other things, too, which fans might prefer to overlook—an unrepentant philanderer and an opportunistic egotist reluctant to give credit when due, and even more reluctant to share the monetary rewards of his success. These tendencies led to numerous personal and professional rifts during the production of the classic Star Trek series, conflicts that only escalated in later years when the financial stakes were higher.

Like many great storytellers, Roddenberry frequently took creative license with his own recollections. For biographers and historians, this is not only a vexing trait but also a puzzling one, considering how colorful his life truly was. If ever a story could stand on its own merits, it was Roddenberry’s. Even before he seized upon the idea that would become Star Trek, he had already piled up several lifetimes worth of drama as a decorated war veteran, a commercial pilot (and plane crash survivor), a Los Angeles police officer, and an award-winning screenwriter and television producer.

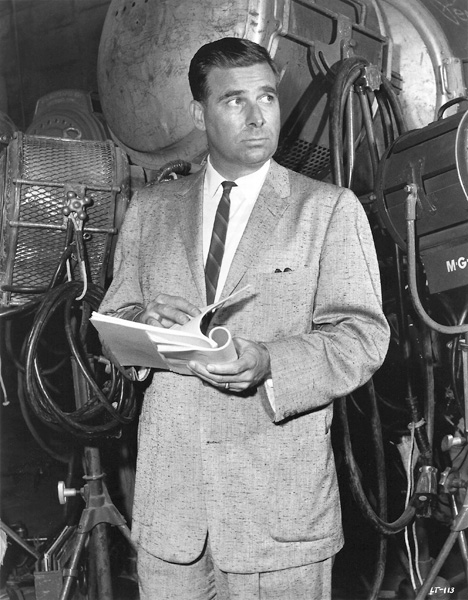

A dashing, young Gene Roddenberry posed for this publicity still during production of his first TV series, The Lieutenant (1963–64).

Let That Be Your Last Battlefield (Early life and military career, 1921–45)

Eugene Wesley Roddenberry was born August 19, 1921, in El Paso, Texas, but moved to Southern California when he was barely a year old. His father, Eugene Edward Roddenberry (“Big Gene” to his family), joined the Los Angeles police force as a beat cop. “Little Gene” was a bright but introverted child who sometimes felt ill at ease in his own home, chafing under the Southern Baptist instruction of his mother, Caroline Goleman Roddenberry, and Big Gene’s vocal racism. Although from all accounts he was a good father, the elder Roddenberry commonly referred to African Americans as “niggers” and Jews as “kikes.” Young Gene escaped his discomfort by reading pulp magazines (he was especially fond of Edgar Rice Burroughs’s John Carter of Mars yarns and E. E. “Doc” Smith’s Skylark series), listening to radio shows (including The Lone Ranger and The Shadow), and going to the movies (where the Flash Gordon serials were favorites). Despite an I.Q. tested in the 99.9th percentile, young Gene made pedestrian grades in high school, where he remained aloof from most of his classmates.

Roddenberry finally emerged from his shell after entering Los Angeles City College in 1939. He was pursuing a criminal justice degree with the intent of following in his father’s footsteps when he began dating Eileen Rexroat, who would later become the first Mrs. Gene Roddenberry. During his second year at LACC, Gene discovered a second love as well—flying. He joined the Civilian Pilot Training Program, an Army Air Corps–sponsored initiative that offered young men no-cost flight instruction. Roddenberry displayed great aptitude and earned his pilot’s license at age nineteen. Following graduation in 1941, he put his law enforcement career on hold and joined the Air Corps. Six months later the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor, and the United States entered World War II.

During the war, Gene piloted reconnaissance and bombing missions, usually in a B-17 Flying Fortress, with the 394th Bombing Squadron, while stationed in Hawaii, Fiji, Guadalcanal and elsewhere in the Pacific theater. Roddenberry claimed to have flown 89 missions, although that number is not verifiable. His planes were often fired upon by antiaircraft guns or attacked by Japanese fighters, but Roddenberry maintained that the most terrifying flight of his career was a recon mission that took his B-17 directly into a typhoon. Blinded by wind and rain, the low-flying plane was nearly smashed by the massive, roiling waves. On August 25, 1943, Roddenberry was attempting to take off from a makeshift airfield on the tiny island of Espiritu Santu when his Flying Fortress crashed, killing two crewmen. An official investigation blamed the accident on mechanical breakdown. A month later, Gene’s unit rotated home, and Roddenberry spent the rest of the war stateside. He was awarded the Distinguished Flying Cross and the Air Medal before leaving what was by then known as the Army Air Force in 1945.

Wink of an Eye (Commercial pilot, 1945–48)

After leaving the service, still infatuated with flying, Roddenberry moved to New Jersey and took a job as a commercial pilot for Pan American World Airways. During his off-hours, Gene (who for years had dabbled at writing poems and songs) took a pair of extension classes in creative writing from Columbia University. But his aviation career was a source of constant worry for Eileen, who feared for her husband’s safety on the long international flights he was routinely assigned by Pan Am—copiloting routes from New York to Johannesburg, South Africa, and to Calcutta, India. Her concerns proved valid in June 1947. Gene was “deadheading” (a pilot flying as a passenger) on Pan Am flight 121 from Karachi, India, to Istanbul, Turkey, when the aircraft suffered an engine fire and crash-landed in the Syrian desert.

Gene survived the crash because, at the request of Captain Joe Hart, he left the flight deck to calm the panicked passengers in the plane’s nearly full cabin and prepare them for the landing attempt. It was about 1:45 a.m. on a moonless night in the pitch-black desert. On impact, the plane’s fuselage was torn in two and a wing was sheared off. Jet fuel spilled and the wreckage was quickly engulfed in flames. Fourteen people died in the crash, including Captain Hart and his copilot. But Roddenberry and two flight attendants helped the other sixteen passengers escape the burning aircraft, collecting first-aid supplies and an inflatable life raft, which was used as a temporary shelter.

Even though he suffered two broken ribs and assorted bruises and cuts during the crash, Roddenberry worked through the night administering first aid to the survivors, some of whom had suffered severe burns. Fortunately, the plane had crashed near the village of Mayadin, Syria. Shortly after sunrise, local villagers descended on the scene, robbing the survivors (and the dead) of their valuables before the Syrian Army arrived to secure the crash site. (At least that’s the official version of events. In his memoir Beam Me Up, Scotty, James Doohan recounts another version of the story. As Roddenberry told the tale to Doohan, the survivors were rescued by a gay Arab sheik who made sexual advances toward Roddenberry. Roddenberry demurred, but feared his refusal would threaten the lives of the survivors. This colorful story may be indicative of the Great Bird’s penchant for embellishing his personal history.) Even after the rescue, however, the ordeal wasn’t over for Roddenberry. He was detained in Damascus for weeks while the Syrian government undertook a slow-moving investigation of the crash. Even after he returned home, he had to testify at a safety inquiry held by the Civil Aeronautics Board in New York, who gave Roddenberry a commendation for his actions related to the crash.

Where His Old Man Had Gone Before (L.A. cop, 1949–56)

Just nine months after he returned from Syria, the Roddenberrys’ first child, Darleen, was born. With a growing family came increasing pressure from Eileen to give up aviation. Roddenberry resigned from Pan Am in May 1948 and moved back to Los Angeles. At age twenty-eight he belatedly took up his law enforcement career, joining the L.A. police force. Initially, he was assigned to direct traffic at the intersection of Fifth and Broadway. Roddenberry’s father walked a beat his entire career. But with keen intelligence and a previously untapped writing ability, Gene rose quickly through the ranks. After just sixteen months on the force, he secured a cushy position writing press releases and speeches for Police Chief Bill Parker. In retrospect, this may seem like an odd pairing, but the bleeding-heart liberal Roddenberry admired and respected the staunchly conservative Parker, who cleaned up a corruption-plagued department and desegregated the force. Roddenberry befriended another young officer, Wilber Clingan, whom he would later immortalize by naming an alien species—the Klingons—in his honor (retaining the pronunciation of Clingan’s name but changing the spelling).

In his eagerness to burnish the image of law enforcement personnel in general and L.A. cops in particular, Chief Parker made common cause with Jack Webb, producer and star of the seminal police drama Dragnet. Webb’s TV show portrayed the LAPD as a clean-cut, efficient, professional organization. In exchange, Parker’s department supplied Webb with real cases on which to base episodes. This is why Dragnet always ended with the announcement that “the story you have just heard is true. Only the names have been changed to protect the innocent.” Roddenberry helped find these stories for Webb and his writers. This wasn’t part of Roddenberry’s official duties; he was paid $100 per story by Dragnet for supplying a one-page treatment based on actual events (usually splitting the fee with the officer involved in the case). In 1953, after selling several stories, and later watching the shows based on his submissions, Roddenberry decided he wanted a hand in the far more lucrative business of writing complete screenplays. Part of his motivation was his enlarging family. Gene and Eileen would welcome a second daughter, Dawn, in 1954. By then he had been contacted by Stanley Sheldon, a former captain in the LAPD Public Information office now working with Ziv Television Productions, who asked Roddenberry if he would be interested in serving as technical advisor for a new syndicated program called Mr. District Attorney. Although still employed as a police officer, Roddenberry’s television career was underway.

The Squire of Hollywood (Screenwriter and TV producer, 1957–64)

Roddenberry quickly graduated from technical advisor to full-fledged screenwriter, providing teleplays for Mr. District Attorney and other Ziv-produced series, such as Highway Patrol, under the pseudonym Robert Wesley. By 1956, police Sergeant Gene Roddenberry was pulling in more money from television than from law enforcement, and after seven years of service he resigned his post with the LAPD. Over the next several years, Roddenberry’s profile—and his income—increased dramatically. Now writing under his own name, he eventually left Ziv, whose shows were syndicated to stations across the U.S. for broadcast in non-prime-time slots, and began writing for major network programs such as Dr. Kildare, The Virginian, Have Gun—Will Travel, and corporate-sponsored dramatic anthologies, including Chevron Hall of Stars, the Kaiser Aluminum Hour, and The DuPont Show. For his Have Gun script “Helen of Abiginian,” Roddenberry won a Writers Guild of America award in 1958. In this offbeat episode, bounty hunter Paladin (Richard Boone) retrieves an Armenian dancer who tries to elope with a passing cowboy. Paladin collects a $1,000 reward from the girl’s father, allays the man’s concerns about his daughter’s marriage, and plays cupid when the prospective groom gets cold feet.

Despite the accolades and paychecks that were rolling in, Roddenberry began to grow frustrated. Like many scriptwriters, he often was unhappy with the way his work was translated to the screen. And he recognized that the real money lay in creating the series, not in writing the episodes. In 1960, he landed a high-paying gig ($100,000 per year plus profit participation) with Screen Gems Television generating concepts for development. In less than eighteen months with Screen Gems, Roddenberry provided ideas, outlines, and in some cases full pilot screenplays for nearly a dozen proposed series, including two—the war drama APO 923 and Defiance County, about a small-town D.A.—for which unsold pilots were produced. Even though the financial rewards of Gene’s endeavors were significant, and despite her gratitude that he was no longer piloting, Eileen Roddenberry was increasingly unhappy with the direction of her husband’s career. She was uncomfortable with the late nights and socializing that were part and parcel of the Hollywood lifestyle, and she worried about Gene’s relationships with the young actresses he came into contact with. Once again, her concerns were validated as Roddenberry, dissatisfied with Eileen, indulged in trysts with several ingénues and launched a full-fledged, long-term affair with a young actress who would eventually become his second wife.

Marital issues aside, Roddenberry’s fortunes continued their rapid ascent. After leaving Screen Gems, working for Arena Productions in partnership with Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer, he created his first successful pilot, which sold in 1962. NBC picked up Roddenberry’s peacetime military drama The Lieutenant, starring Gary Lockwood as the titular Marine Corps officer, and future Man from U.N.C.L.E. Robert Vaughn as Lockwood’s superior. Each week Lt. William Tiberius Rice (Lockwood) helped recruits, active-duty personnel, and even retired marines meet the personal challenges that accompany military service. To reduce costs and increase realism, The Lieutenant was shot at Camp Pendleton, the West Coast training facility for the U.S. Marines, and carried a seal of approval from the Corps. However, Roddenberry was frustrated with restrictions placed on him by the Marines, who nixed any story idea that portrayed servicemen in an unfavorable light. Despite generally favorable reviews, the show ran just one season, 1963–64. Appearing Saturdays from 7:30 to 8:30, The Lieutenant was outperformed in the Nielsen ratings by The Jackie Gleason Show on CBS and the folk music program Hootenanny on ABC. The changing political climate, with escalating American involvement in the Vietnamese civil war, may have also played a part in NBC’s decision to scuttle the series. During its short run, however, Roddenberry worked with key personnel who would serve him well in future endeavors, including director Marc Daniels, screenwriters Gene Coon and Dorothy Fontana, casting director Joe D’Agosta, and actors Leonard Nimoy, Nichelle Nichols, Walter Koenig, and Majel Barrett.

By the time NBC had decommissioned The Lieutenant, Roddenberry already had two more series concepts typed up. One of these was a straightforward cop show then called Assignment 100 but later retitled Police Story (not to be confused with the Joseph Wambaugh series of the same name that ran from 1973 to 1977). The other was an ambitious proposal for a weekly science fiction program chronicling the spacefaring adventures of Captain Robert T. April and the crew of the starship Yorktown. A few details still needed to be refined, but Star Trek was on the drawing board. Its journey from page to screen, however, would prove far longer and more convoluted than Roddenberry (or anyone else) could have possibly imagined.