2

Credited and Uncredited Influences on the Creation of Star Trek

Star Trek did not spring forth fully formed from the mind of producer-creator Gene Roddenberry like some golden egg laid by the Great Bird of the Galaxy. Many elements now considered essential to the mythology and appeal of the franchise did not originate with Roddenberry at all, but were introduced later by screenwriters such as Gene L. Coon (who invented the Klingons and the Prime Directive), and Theodore Sturgeon and Dorothy Fontana (who developed the coolly logical Vulcan culture in episodes such as “Amok Time” and “Journey to Babel”). Roddenberry himself stressed this, although he struggled to verbalize the creative process that led him to create the series. “I don’t say that Star Trek was created in an instant,” the producer told interviewer Yvonne Fern in her book Gene Roddenberry: The Last Conversation. “No, it evolved. And a good many people contributed to its evolution. But overall the idea came rather—well, it just came!”

Yes, but where did it come from?

Contrary to popular belief, few of Roddenberry’s ideas for Star Trek were truly new or innovative. Like most creative breakthroughs, Trek was a synthesis of familiar elements, recognizable blocks assembled in an exciting new configuration. Star Trek stood apart due to the diversity of Roddenberry’s sources of inspiration, the seamlessness with which he melded those influences, and his unifying vision of a promising future for the human race. Here are the most prominent component parts that Roddenberry used in creating Star Trek, many of which he acknowledged during his lifetime and some of which he did not:

Gulliver’s Travels (1726) by Jonathan Swift

One of the immortal works of English literature, Irishman Jonathan Swift’s Gulliver’s Travels (or, to use the novel’s formal title, Travels Into Several Remote Nations of the World by Captain Lemuel Gulliver) is at once a delightful fantasy-adventure, a witty parody of the popular traveler’s narratives of the early eighteenth century, and a scathing satire of the eighteenth-century English government and Anglican church. The book is divided into four parts, each chronicling a fantastic voyage by Gulliver and each making its own satirical point. The first of these—in which Gulliver is shipwrecked on the island of Lilliput and taken prisoner by its inhabitants, who are one-twelfth his size—remains perennially popular with young readers and is often abridged for a juvenile audience. Gulliver, after single-handedly capturing the entire navy of the rival kingdom of Blefuscu, becomes a favorite of the Lilliputian court (enabling Swift to lampoon the excesses of the court of King George I). Subtle and multilayered, Gulliver’s Travels seems to grow throughout the reader’s lifetime, revealing new insights and implications as its audience become more sophisticated.

From the outset, Roddenberry wanted Star Trek, like Gulliver’s Travels, to function as both fanciful adventure and social commentary. As an ardent political progressive working in the relatively conservative realm of 1960s network television, Roddenberry understood that, like Swift, he would have to disguise his themes in fantasy. While he may have lacked Swift’s feathery touch, Roddenberry’s program offered thinly veiled statements about the Vietnam War (“A Private Little War”), prejudice (“Balance of Terror”), and segregation (“Let That Be Your Last Battlefield”), among other sensitive topics. “Censorship was so bad that if he could take things and switch them around and maybe paint somebody green and perhaps put weird outfits on them and so forth, he could get some of his ideas across,” said his widow, Majel Barrett Roddenberry, in an interview featured on the Star Trek: The Motion Picture DVD. “He got lots of ideas through and that’s how Star Trek was born.”

In fact, while spitballing ideas with Desilu executive Herb Solow in 1964 during development of the treatment for Star Trek’s original pilot, Roddenberry briefly considered changing the name of the starship’s leader to Captain Gulliver and retitling the program Gulliver’s Travels. Fortunately, according to executive Herb Solow (in his book Star Trek: The Inside Story, coauthored with Bob Justman), cooler heads prevailed, and the show’s original title was restored—although a dozen other captain’s names were considered before Roddenberry finally settled on James T. Kirk.

The Horatio Hornblower Novels (1937–62) by C. S. Forester

Not only did the captain’s name change, but so did his personality. Roddenberry’s original model for Kirk was Horatio Hornblower, the brooding hero of C. S. Forester’s seafaring adventure yarns, set during the Napoleonic Wars. Introduced in The Happy Return, a 1937 tale known in the U.S. as Beat to Quarters, Hornblower starred in eleven novels and three short stories, becoming far and away the most famous creation of Cairo-born English novelist Cecil Louis Troughton Smith, who adopted the pen name C. S. Forester. Captain Hornblower is quiet and introspective, vexed by self-doubt and seasickness. Acutely aware of his responsibilities to his ship and its crew, command weighs on him heavily. When readers first meet Hornblower, on page four of Beat to Quarters, he is silently pacing the deck. “Up and down, up and down … he was entirely lost in thought.”

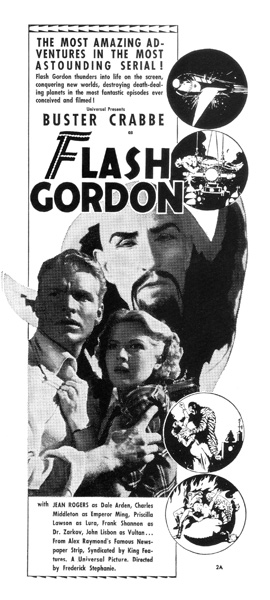

Pressbook ad for the 1936 serial Flash Gordon, a childhood favorite of Gene Roddenberry.

Such a character may seem oceans away from William Shatner’s energetic, swashbuckling Captain Kirk. Yet in his original outline for the series, created to help him sell Star Trek to prospective production studios, Roddenberry describes his starship captain (then named Robert T. April) as “a space-age Captain Horatio Hornblower. … A strong, complex personality, he is capable of action and decision which can verge on the heroic—and at the same time lives in a continual battle with self-doubt and the loneliness of command.” The parallel is most apparent in the series’ original, rejected pilot, “The Cage,” which features Jeffrey Hunter as the pensive Captain Christopher Pike. In a strongly Hornbloweresque scene, Pike reveals to his ship’s chief surgeon that he is considering resigning his commission: “I’m tired of being responsible for 203 lives,” Pike says. “Tired of deciding which mission is too risky and which isn’t … who lives—and who dies.” In the second Trek pilot, “Where No Man Has Gone Before,” Kirk broods, Hornblower-like, over how to deal with Lieutenant Commander Gary Mitchell (Gary Lockwood), who has gained superhuman telekinetic powers. As Spock matter-of-factly lays out the options for neutralizing the increasingly dangerous Mitchell, Kirk turns away and stares into space—clearly agonizing over a decision that pits the life of a friend and trusted crew member against the safety of his ship. As the series progressed and Shatner’s more upbeat, confident take on the character took hold, such moments became increasingly rare.

Ultimately, the most enduring vestige of Roddenberry’s Hornblower fascination lies in the nautical jargon used aboard the starship Enterprise. Seeking ways to both enhance realism and help viewers unaccustomed to science fiction become acclimated quickly, Roddenberry and his writers adopted naval terminology: The Enterprise (always referred to in the feminine) had decks, not floors; there was no right or left, only port and starboard; no front and back, only fore and aft. Kirk kept a “captain’s log.” He and his crew were members of Starfleet. This approach worked beautifully, bringing a note of casual verisimilitude to the dialogue while making the futuristic setting seem familiar.

Flash Gordon (1934–43) by Alex Raymond

One of the inspirations Roddenberry frequently credited for Star Trek was Flash Gordon. Cartoonist Alex Raymond’s seminal space opera remains one of the best-loved and most influential works in the history of science fiction. Virtually every spacefaring sci-fi adventure owes a debt to Raymond’s creation, which began as a newspaper comic strip, became one of the great movie serials and was later adapted for radio, comic books, novels, TV, and feature films.

Flash Gordon debuted on January 7, 1934. Raymond created the strip to compete with illustrator Dick Calkins’s futuristic Buck Rogers, which had premiered five years earlier. Thanks to Raymond’s wildly imaginative scenarios and beautifully rendered artwork, Flash Gordon eventually eclipsed Buck Rogers in terms of circulation and fan interest, although today casual fans sometimes confuse the two characters. Flash Gordon is an athletic Yale graduate and polo enthusiast who accidentally becomes embroiled in an interplanetary war between Earth and the planet Mongo, ruled by Ming the Merciless. Flash and his companions (girlfriend Dale Arden and eccentric scientist Dr. Hans Zarkov) are kidnapped and taken to Mongo, where they escape and have numerous adventures foiling Ming’s plans to conquer Earth. On Mongo, our heroes are befriended by Prince Thun of the Lion Men and travel to the forest kingdom of Arboria, the ice kingdom of Frigia, the jungle kingdom of Tropica, the undersea kingdom of the Shark Men, and the flying city of the Hawkmen. Eventually, after spending years on Mongo, Flash and his friends would defeat Ming and go on to new adventures on other alien worlds. By then, however, Flash Gordon had found a second life on motion picture screens.

Universal Pictures’ thirteen-chapter serial Flash Gordon (1936), starring former Olympic swimmer Charles “Buster” Crabbe in the title role, followed the plot of Raymond’s strip with reasonable fidelity. The serial proved extremely successful and spawned two sequels, Flash Gordon’s Trip to Mars (1938) and Flash Gordon Conquers the Universe (1940), all headlined by Crabbe. Despite their low-budget production values and badly dated costumes and visual effects, the Flash Gordon serials feature some of the most iconic imagery in all of science fiction cinema, including their smoke-belching rocket ships and spark-spewing ray guns. Roddenberry was a fan of both the serials, which were syndicated and reran on television into the 1970s, as well as the comic strip, which continued under the direction of various writers and artists until 2003.

The influence of Flash Gordon on Star Trek becomes most apparent when the Enterprise squares off against the evil galactic empires of the Klingons and Romulans in episodes such as “Errand of Mercy” and “The Enterprise Incident,” or when Kirk battles alien monsters in rock-’em, sock-‘em yarns like “Arena” (featuring the Gorn, a giant lizard) and “A Private Little War” (with the Mugato, a horn-headed white gorilla). But the underlying concept of space travelers venturing to new worlds, meeting strange creatures (some friendly, others hostile), getting into various predicaments and often having to slug their way out is straight out of Flash Gordon. In the 1990s, the Star Trek franchise paid tribute to the legacy of Flash Gordon by having helmsman Tom Paris and ensign Harry Kim play out the adventures of the fictional character “Captain Proton” (in black and white, no less) on the holodeck of the starship Voyager. These seriocomic episodes were designed to emulate the look and feel of the classic Flash Gordon serials of the 1930s, right down to the cheesy costumes and antiquated special effects.

Pulp Magazine Covers (1920s–50s)

As a boy, Roddenberry enjoyed all the diversions youngsters of his generation embraced—not only movies and comic strips but also radio serials (especially The Lone Ranger and The Shadow) and especially pulp magazines (so called because they were printed on cheap, rough paper with ragged edges). In recollections quoted in David Alexander’s biography of Roddenberry, Star Trek Creator, Roddenberry’s boyhood friend Ray Johnson remembers the future Great Bird reading Amazing Stories and Astounding Science Fiction for hours on end, becoming so engrossed in the tales that he lost all awareness of the world around him. And Dean Scurr, a high school classmate of Roddenberry’s, recalls young Gene habitually reading science fiction in class, hiding magazines behind his textbook so he appeared to be studying.

Science fiction was born in the pulps—the term was coined by Amazing Stories publisher Hugo Gernsback—and esteemed authors such as Isaac Asimov, Ray Bradbury, Arthur C. Clarke, and Robert A. Heinlein launched their careers there. Nevertheless, most pulp fiction was clumsy and formulaic, catering to the assembly line–like needs of critically disreputable magazines churning out 128 pages of content per month. To entice prospective buyers to plunk down their dime for the latest issue, publishers relied largely on eye-catching, sometimes lurid painted cover illustrations. Artist Frank R. Paul’s dramatic artwork, usually featuring elegant spaceships or grotesque monsters, helped sell Amazing Stories and other pulps from the late 1920s through the early 1950s. His bold and imaginative illustrations were as pivotal as the work of any writer in helping the fledgling sci-fi genre find an audience. Accordingly, when the first World Science Fiction Convention met in New York in 1939, rather than an author, Paul was chosen as the Guest of Honor. The work of artist Earle K. Bergey, which often featured scantily clad buxom women, also proved popular and influential. Illustrators Leo Morey, Howard V. Brown, Alex Schomburg, and, later, Frank Kelly Freas also left a mark on the genre with striking cover art.

In the 1960s, when Roddenberry was preparing to shoot the first Star Trek pilot, he drew inspiration from pulp cover images. Screenwriter Samuel Peeples, an avid collector of sci-fi pulps, reports that Roddenberry asked to photograph the covers of several magazines from his extensive collection. Later, Roddenberry passed along the photos to art director Matt Jefferies, who designed the Enterprise and other Star Trek spacecraft. Among the images Roddenberry gave Jefferies was Frank R. Paul’s cover for the October 1953 issue of Science Fiction Plus, edited by Hugo Gernsback, featuring a spaceship with many design similarities to the Enterprise, including two cylindrical rocket engines separated from the main body of the craft by long struts. Roddenberry also provided pulp covers, including those by Earle K. Bergey, as guidelines for production designer Bill Theiss, who designed futuristic (and usually skimpy) costumes for Star Trek’s female guest stars.

Space Cadet (1948) by Robert A. Heinlein

One of the most obvious antecedents of Star Trek was Space Cadet, an early novel published by Robert A. Heinlein, later revered as “the dean of science fiction writers.” Like his contemporaries Isaac Asimov and Arthur C. Clarke, Heinlein rose through the ranks of editor John W. Campbell’s Astounding Science Fiction magazine, which published many of Heinlein’s short stories and serialized some of his novels. Heinlein helped raise the genre’s standards in terms of both scientific plausibility and literary merit. He won numerous Hugo and Nebula awards over the years, and in 1974 was given the first Grand Master Award for lifetime achievement from the Science Fiction Writers of America.

Roddenberry may have been influenced by Heinlein’s “future history” stories, which were interrelated tales that bolstered believability by taking place at various points along a single imaginary timeline stretching from the middle of the twentieth century to the early twenty-third century. During Star Trek’s three-season run on NBC, Roddenberry worked with script supervisors including Dorothy Fontana to assure that the details of his program’s “historical background” remained consistent. In the decades since, the writers and producers of various Trek series and movies have protected Roddenberry’s Heinlein-like commitment to continuity, keeping the sprawling Star Trek mythos remarkably coherent and logical. On a broader level, the social and political themes expressed on Star Trek often ran along lines similar to Heinlein’s libertarian humanism. Heinlein was especially strong in his rejection of segregation or racism of any sort, a theme that recurs frequently in Star Trek. (In this aspect, Roddenberry may also have been inspired by the work of Eric Frank Russell, whose tales about the crew of the starship Marathon were among the first sci-fi stories to feature African American characters without racial stereotyping.)

Clearly, however, Roddenberry drew from Space Cadet, one of Heinlein’s early “juvenile” novels. Although aimed at young readers, these action-packed books featuring youthful protagonists never compromised Heinlein’s high standards for scientific accuracy or polished word craft, and remain among his most enduringly popular works. Space Cadet follows teenager Matthew Dodson as he struggles through the arduous training required to join the Interplanetary Patrol, and chronicles his first adventures as a novice Patrolman. The similarities between Space Cadet and Star Trek are numerous. Among the most striking: Space Cadet’s Solar Federation, like Star Trek’s United Federation of Planets, is a utopian meritocracy (and, informally, both are referred to as simply “the Federation”). The Interplanetary Patrol, like Starfleet, is a precision-tuned military organization of high moral character on a peaceful mission (to protect the well-being of humans and other beings throughout the solar system). Like Starfleet, its membership includes persons of all races and nationalities, including off-worlders. And coincidentally (or not), Matthew Dodson and James T. Kirk both hail from Iowa. These commonalities were thrown into sharp relief by producer J. J. Abrams’s 2009 motion picture Star Trek, which “rebooted” the franchise by taking the story back to Kirk’s days as a cadet at Starfleet Academy.

Note: Although Roddenberry insisted Starfleet was “paramilitary” rather than military, the organization’s naval nomenclature and iconography, along with Captain Kirk’s tendency to refer to himself as “a soldier,” makes this distinction difficult to support.

The Voyage of the Space Beagle (1950) by A. E. van Vogt

Another of the inspirations Roddenberry readily acknowledged for Star Trek was The Voyage of the Space Beagle, a glittering gem of sci-fi adventure from Canadian author Alfred Elton van Vogt. Van Vogt was yet another of the many authors discovered by John W. Campbell and frequently published in Astounding Science Fiction during the 1930s and ’40s. Van Vogt’s punchy prose and lightning-paced, thought-provoking plots, often involving journeys through space or time, were extremely popular and inspired later writers, including Harlan Ellison and Philip K. Dick. The Voyage of the Space Beagle, like many of van Vogt’s novels, was what the author called a “fix up,” cobbled together by linking four previously published short stories: “Black Destroyer” (1938), “Discord in Scarlet” (1939), “M33 in Andromeda” (1943), and “War of Nerves” (1950). Despite its ungainly, episodic structure, The Voyage of the Space Beagle remains a thrilling read. The Beagle (named in honor of Charles Darwin’s ship, the H.M.S. Beagle) is an Earth spacecraft inhabited by hundreds of scientists on a decades-long mission of galactic exploration. The explorers encounter several sentient extraterrestrial species, most of them hostile, including the Courl, a race of pantherlike carnivores with tentacles sprouting from their shoulders; the birdlike, telepathic Riim; the Ixtl, last survivor of an ancient race, which invades the ship and lays its eggs in several members of the Beagle’s crew; and Anabis, a noncorporeal consciousness that feeds on the deaths of other living beings. Even casual viewers of Star Trek will immediately recognize parallels between the exploits of the starship Enterprise and those of the Beagle. For instance, how many times did Kirk and Spock encounter beings made of “pure energy”?

An early edition of Robert A. Heinlein’s 1948 novel Space Cadet, which Roddenberry often named as a primary inspiration for Star Trek.

Photo courtesy of Lisa Meier

To enhance Star Trek’s credibility within the science fiction community (he badly wanted the series to be taken seriously by the genre’s fans and professionals), Roddenberry recruited prominent sci-fi authors to write episodes. Many of the luminaries he drafted into service for Star Trek contributed outstanding shows: Harlan Ellison wrote “The City on the Edge of Forever,” widely regarded as the series’ single best episode; Theodore Sturgeon penned “Amok Time,” the first story to delve deeply into the Vulcan culture; and horror specialist Robert Bloch delivered the characteristically creepy “Wolf in the Fold” (about an Anabis-like noncorporeal being that feeds on fear). However, not every author Roddenberry approached could adjust to the specialized demands of writing for TV. Van Vogt, although among the first writers Roddenberry tapped to work for Trek, was one of those who never managed to develop a satisfactory treatment. Nevertheless, his influence on the series remains significant.

Childhood’s End (1953) by Arthur C. Clarke

The development of First Officer Spock was even more labored and convoluted than that of Captain Kirk. The unflappably logical half-Vulcan science officer played by Leonard Nimoy bears very little similarity to Roddenberry’s original vision of the character. It’s possible that Spock—at least in his nascent form—may owe his existence in part to British author Arthur C. Clarke’s acclaimed novel Childhood’s End. Clarke wrote several Hugo and Nebula Award–winning novels, but remains best known as the coauthor of the screenplay for director Stanley Kubrick’s masterpiece 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968). Childhood’s End, the third of Clarke’s fifteen novels, was expanded from an earlier short story, “Guardian Angel” (1950). At the height of the Cold War, with Eastern and Western powers vying to land the first rocket on the moon, a race of benevolent extraterrestrials arrives on Earth, promising to bring peace and prosperity—but refusing to reveal themselves until fifty years have elapsed. Once the aliens, known as the Overlords, finally emerge, it becomes obvious why they have been in hiding for five decades. Red-faced bipeds with horns, spaded tails and leathery wings, they resemble Earth’s mythological demons. Humankind’s association of their physical appearance with satanic evil is written off as vestigial evidence of an unsuccessful prehistoric encounter between humans and the Overlords. But a few human skeptics remain wary of their benefactors …

Roddenberry was well-acquainted with Childhood’s End (he discusses the novel in some depth with author Yvonne Fern in her interview book Gene Roddenberry: The Last Conversation) and appears to have been fascinated by the idea of friendly aliens who are devilish in appearance. In his original outline for Star Trek, Roddenberry describes Spock as “almost frightening—a face so heavy lidded and satanic you might expect him to have a forked tail. … Half-Martian, he has a slightly reddish complexion and semipointed ears. But—strangely—Mr. Spock’s temperament is in dramatic contrast to his satanic look.” This Spock was not detached and clinical, but warm and amiable, with “an almost catlike curiosity over anything the slightest [bit] ‘alien.’” In makeup tests for the first Trek pilot, “The Cage,” Nimoy was painted red. The face paint was discarded after tests showed that, viewed in black and white, the red Spock came out looking like an African American satyr. (Even though Star Trek was broadcast in color, in 1966 most Americans still had black-and-white TVs.)

Roddenberry’s insistence on Spock’s demonic appearance—especially the pointed ears—nearly derailed the entire project. The network’s sales staff feared that the character would make the series tough to market in the Bible Belt and warned that some affiliates might decline to broadcast the show. (These anxieties proved baseless.) A photo of Spock included in NBC’s advance promotional booklet for Star Trek was airbrushed to smooth out Spock’s pointed ears and reshape his eyebrows. Earlier, when it granted Roddenberry the extraordinary opportunity to shoot a second pilot, NBC requested several changes to the program—including the elimination of Mr. Spock. Roddenberry steadfastly refused, preferring to abandon Star Trek altogether rather than go forward without this key character. All this despite the fact that in “The Cage” Spock was so thinly written he had no discernible personality. Apparently Roddenberry was simply fixated on the Clarkean conceit of a kindly “devil.”

Forbidden Planet (1956)

Roddenberry screened Forbidden Planet (1956) for his creative team during preproduction of the first Star Trek pilot, but the film’s influence on the series has been overstated.

The impact of Forbidden Planet on Star Trek is undeniable but perhaps overstated.

The 1950s rang in the first heyday of science fiction cinema with the release of classics such as The Thing from Another World, The Day the Earth Stood Still (both 1951), War of the Worlds (1953), and scores of other sci-fi hits. Even in its day, however, Forbidden Planet was something special—not simply an earthbound monster movie dressed up in science fictional trappings, but thoughtful, spacefaring speculative fiction produced on a lavish scale by a major studio. The story, loosely based on William Shakespeare’s The Tempest, sends Commander John J. Adams (played by Leslie Nielsen—yes, that Leslie Nielsen) and his United Planets space cruiser to Altair IV to investigate what happened to a group of colonists who attempted to settle the planet twenty years earlier. Adams learns that during the early days of the colony a mysterious unseen creature killed most of the settlers and destroyed their spaceship. Altair IV—in the dim past home to a mighty, superscientific race known as the Krell—is now inhabited only by the colonists’ reclusive former leader Dr. Morbius (Walter Pidgeon), his beautiful nineteen-year-old daughter (Anne Francis), and their mechanical manservant Robbie the Robot. Then the invisible monster, unheard from for twenty years, returns and begins killing members of Adams’s crew …

Roddenberry freely credited Forbidden Planet as an inspiration for Star Trek, which is hardly surprising. It was thought-provoking, thrill-packed sci-fi adventure, complete with spaceships, robots, laser guns, aliens, and monsters—everything he (and most other sci-fi fans) loved. Moreover, Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer, the studio that made The Wizard of Oz and Gone with the Wind, brought the full power of its spectacular production capabilities to bear on the project, and it shows—especially in the picture’s sometimes breathtaking production design and Oscar-nominated visual effects. Forbidden Planet offered something Star Trek could aspire to.

There are marked similarities between Star Trek and Forbidden Planet. For example, like Trek, Forbidden Planet involves a peace-loving interstellar military organization in service of an interplanetary government and features a tough-minded captain who’s chummy with the ship’s physician. The movie’s plot proves similar to that of several Star Trek episodes, including the first ever broadcast, “The Man Trap” (featuring the reclusive Professor Crater and the shape-shifting Salt Vampire).

Nevertheless, Roddenberry did not—as detractors have sometimes claimed—simply change Forbidden Planet’s character names and uniform colors to create Star Trek. Most elements shared by Forbidden Planet and Star Trek originate not with the film but in sci-fi literature, like Heinlein’s Space Cadet. And key components in Star Trek’s appeal—such as its interracial crew, including a prominent nonhuman—are absent from Forbidden Planet. It’s true that Roddenberry screened Forbidden Planet during preproduction of the first Star Trek pilot (in a memo, he even suggested trying to buy a print or acquire frame enlargements from the film), but he did so for the benefit of art director Matt Jefferies and his production design team, who were creating sets, props, and models for the show. Ultimately, the Enterprise, its interiors, and Starfleet-issue equipment bore little resemblance to their counterparts in Forbidden Planet. (Producer Irwin Allen’s rival TV series Lost in Space, a simplistic program seldom compared to the cerebral Forbidden Planet, displays just as many significant commonalities with the film, including its saucer-shaped Jupiter 2 spacecraft—very similar to Planet’s C57-D cruiser both in exterior design and interior layout—and the presence of a show-stealing Robot.)

Wagon Train (1957–65)

While pitching Star Trek to prospective production studios and, later, to broadcast networks, Roddenberry invariably referred to his project as “Wagon Train to the stars.” There are indeed basic conceptual similarities between the two programs. TV’s Wagon Train, inspired by director John Ford’s 1950 Western Wagonmaster, followed the exploits of wagon master Seth Adams (Ward Bond) as he and his trail-hardened assistants led tenderfoot settlers from Missouri to California, becoming embroiled in complications of all sorts during stops along the way. (When Bond died in the middle of the show’s fourth season, his character was replaced without explanation by wagon master Christopher Hale, played by John McIntire.) Like the starship Enterprise, the wagon train often would approach a settlement, send out a search party, and run into trouble, a quandary that usually forced the wagon master or his fellow travelers to wrestle with some moral issue. As with Trek, many episodes featured a recognizable guest star (among the luminaries who appeared during Wagon Train’s 284-episode run were Bette Davis, Peter Lorre, and Lou Costello). Inevitably the dilemma would be resolved by the end of the show, and the train would trundle off to its next adventure, in much the same manner that Captain Kirk and company would leave orbit and warp away into the unknown. All this suggests that Wagon Train may have provided Roddenberry with a structural template upon which to build his science fiction idea. That’s certainly possible.

However, it’s equally likely that Roddenberry simply used the Wagon Train parallels as shorthand to help him explain Star Trek to dubious executives who knew nothing of, and cared less about, science fiction. His actual inspiration could have been something entirely different. (The basic narrative structure of The Voyage of the Space Beagle, as well as Gulliver’s Travels, is much the same as both Trek and Wagon Train.) Roddenberry later admitted that he, somewhat disingenuously, tried to pass off Star Trek as an outer space version of cowboys and Indians. His attempt to equate Star Trek with Westerns was carefully calculated. Not only did television bosses understand Westerns better than sci-fi, Westerns were bankable commodities in the 1950s and ’60s.

During the 1958–59 season, for example, half of TV’s twenty-eight best-rated shows were Westerns, including the top four programs (No. 1 Gunsmoke, followed by Wagon Train, Have Gun—Will Travel, and The Rifleman). And Roddenberry’s choice of Wagon Train as Trek’s Old West counterpart was particularly well considered. The venerable series ran for eight seasons, as long as any TV Western except Gunsmoke, Bonanza, and The Virginian. It spent half of that time in the Nielsen Top 10 and was the top-rated program for the 1961–62 season. However, the tactic of “disguising” Star Trek as a Western nearly backfired. When Roddenberry delivered “The Cage,” Star Trek’s original pilot, it bore few similarities to Wagon Train or any other Western ever made. Executives felt misled and rejected “The Cage.” Fortunately, Roddenberry was given a second chance, and Star Trek took flight.