6

Memorable Pre-Trek Roles for William Shatner

While most Star Trek cast members came to the program without a great deal of on-screen experience or audience recognition, William Shatner already had assembled an impressive résumé, playing small roles in big movies, big roles in small movies, and earning acclaim for his performances on stage and television. He had proven himself adept with both high drama and low comedy. And even though two previous TV series starring Shatner quickly fizzled, the actor had become familiar to viewers through his frequent guest appearances on dozens of other programs. The camera liked Shatner’s face, and producers liked his professionalism and work ethic.

Although he usually played WASPy Americans, Shatner was Jewish, born in Quebec on March 22, 1931, the son of Joseph Shatner, a Central European haberdasher who had immigrated to Canada and founded a modestly successful company that manufactured inexpensive suits. Joseph wanted young Bill to take over the family business and was appalled when his son took up a theatrical career instead. Nevertheless, Joseph Shatner instilled in his son an abiding commitment to an honest day’s labor. Such dedication would serve the actor well throughout his career, even though it failed to translate into wealth and fame prior to Star Trek.

Henry V in Stratford, Ontario (1954)

An actor’s career is a series of chain reactions, with one good performance opening up new opportunities (or a bad one closing them off), solid work in those subsequent roles leading to further opportunities, and so on. For William Shatner, a single performance as Henry V provided the initial thrust that launched his professional career.

After leaving his father’s haberdashery (where he had worked packing suits), Shatner joined the Canadian National Repertory Theatre in Ottawa (where he earned thirty-one dollars per week), summering at the Mountain Playhouse back home in Montreal. A few years later, at age twenty-three, he joined the prestigious Stratford Festival in Ontario for three seasons, beginning in 1954. As one of a half-dozen young actors in the company, he was initially assigned minor parts, such as the Duke of Gloucester, his role in the company’s 1954 production of Shakespeare’s King Henry V. However, Shatner was also selected to understudy star Christopher Plummer—although he had no expectation he would actually be called upon to replace Plummer. Nevertheless, Plummer was struck down by a kidney stone, and Shatner was asked to fill in on short notice. Owing to a brief rehearsal schedule, there had been no understudy’s run-through. At this distance, since the performance was not filmed, we must rely on the actor’s recollection of the event in his autobiography Up Till Now. According to Shatner, things went “inexplicably” well until the very end, when he momentarily went blank but managed to cover his panic until the final lines of the play came back to him.

It wasn’t quite the Hollywood cliché—“You’re going out there a nobody, but you’re coming back a star!”—but his surprisingly well-received performance as Henry V proved to be Shatner’s first big break. It impressed festival director Tyrone Guthrie, who cast the actor in a leading role in his production of Christopher Marlowe’s Tamburlaine the Great. After a successful Canadian run, Guthrie moved Tamburlaine to Broadway, where Shatner made his debut on the Great White Way. And that, in turn, led to further opportunities.

Ranger Bob on Howdy Doody (1954)

Although Shatner elected to return to Stratford for two more seasons, his work in Tamburlaine the Great attracted several offers for additional, off-season work in film and television, including his first recurring role on a TV series—as Ranger Bob on the beloved NBC children’s program Howdy Doody. From December 1947 through September 1960, ventriloquist “Buffalo” Bob Smith costarred with the wooden-headed Howdy Doody and a clown named Clarabelle (originally played by Bob Keeshan, the future Captain Kangaroo) on this Western-themed show, shot in front of a live audience of kids who actively participated in the program (even singing the theme song) from the “peanut gallery.” Although it’s cherished by baby boomers who grew up with the program, Howdy Doody isn’t fondly remembered by Shatner. As a young actor with big ambitions—to say nothing of ego—he was frustrated playing a subservient role to a freckle-faced marionette and a clown who communicated by honking a horn rather than speaking. He soon quit Howdy Doody. It was an ignominious beginning to one of the great careers in television history. Who could have foreseen that Shatner would eventually star in four successful series—Star Trek, T. J. Hooker, Rescue 911, and Boston Legal—spanning more than four decades in the industry?

Westinghouse Studio One: Episodes “The Defenders, Parts 1 and 2” (1957)

At first, Shatner enjoyed most of his TV successes on the corporate-sponsored weekly dramatic programs that were staples of the medium’s Golden Age, including the Goodyear Television Playhouse, Playhouse 90, Kraft Television Theatre, the Hallmark Hall of Fame, and the U.S. Steel Hour. One of the most popular of these programs was Westinghouse Studio One. In 1957, Ralph Bellamy and Shatner costarred as a father-and-son legal team in a two-part Studio One courtroom drama titled “The Defenders.” By resorting to courtroom theatrics, Shatner’s character loses his father’s respect but wins the case, saving a young man (played by Steve McQueen) falsely accused of murder. The show earned rave reviews and high ratings, so CBS decided to develop it as an ongoing series. Shatner and Bellamy were offered the leads, but both turned it down. The Defenders went on to a successful four-season run with E. G. Marshall and a young Robert Reed (future patriarch of The Brady Bunch) as the father-and-son lawyers.

Around this same time, Shatner also turned down a studio contract offer from Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer and (perhaps surprisingly, given the actor’s later success as a pitchman) numerous commercials. He wanted to pursue more glamorous roles on Broadway—and landed one as the male lead in the romance The World of Suzie Wong, which opened in 1958 and ran for fourteen months. Starring in the title role was the French-Vietnamese actress France Nuyen, who would later appear as the titular alien princess in the Star Trek episode “Elaan of Troyius.” Shatner earned kind notices (as well as $750 per week), but Suzie Wong turned out to be his only Broadway hit.

Meanwhile, financial pressures were mounting. Shatner had married actress Gloria Rand in 1956, and Leslie, the first of the couple’s three daughters, arrived in 1958 (followed by Lisabeth in 1960 and Melanie in 1964). Shatner returned to television to pay the bills but without the advantage of an ongoing series to provide a reliable paycheck. He became an in-demand guest star, appearing on shows ranging from Alfred Hitchcock Presents to Route 66 to Gunsmoke to Dr. Kildare. Ironically, one of the shows Shatner worked on most frequently was The Defenders, where he made five appearances from 1963 to ’65, usually playing either a defendant or a prosecutor.

Thriller Episode “The Hungry Glass” (1961)

The wide variety of TV roles he played during this period helped Shatner both hone his craft and display his abilities. Viewers who know him only as Captain Kirk may be surprised at the range and finesse Shatner displayed in these diverse and often challenging parts. “The Hungry Glass,” an episode of the anthology series Thriller, provides a case in point.

NBC’s Thriller, hosted by the great Boris Karloff, ran for just two seasons (it was clobbered in the ratings by CBS’s The Red Skelton Show) but produced some excellent episodes, picking up creative steam midway through its first season when the show transitioned from Hitchcockian crime-suspense stories to full-tilt, blood-curdling, supernatural horror. First aired January 3, 1961, “The Hungry Glass” was one of the earliest of these new-breed Thriller episodes. In it, newlyweds Gil and Marsha Thrasher (Shatner and Joanna Heyes) buy a haunted mansion, where the vengeful spirit of a vain old woman lives on in the house’s mirrors and other reflective surfaces, luring unsuspecting visitors to their deaths. Shatner’s performance is carefully calibrated: At first he exudes cool confidence, laughing off “local superstition”; then he lets the character’s self-assurance slowly crumble as Gil comes to believe evil spirits are indeed at work; finally, for the story’s frantic climax, he uncorks a full-blown, Shatnerian freak-out. The actor is especially effective in those scenes where Gil tries to hide his growing fears from his wife. Overall, “The Hungry Glass” is a satisfyingly spooky show, and one that helped set the tone for what would follow for Thriller’s next season and a half. This was more like what viewers wanted from a show hosted by horror icon Karloff. Ratings improved enough over the rest of the season to earn the show a renewal.

Shatner was quickly invited back and costarred in the final episode of Thriller’s first season, “The Grim Reaper.” Unfortunately, both the episode and Shatner’s role proved far less memorable than his first outing. This time around, he was cast as the doting nephew of a kooky mystery author who buys a cursed painting. Written by Robert Bloch from a story by Harold Lawlor, the screenplay builds to an E.C. Comics-style “surprise” ending that’s not very surprising. Shatner does what he can, but his character is one-dimensional and his dialogue at times insipid. Coincidentally, in both of his Thriller appearances Shatner appeared alongside future castaways from Gilligan’s Island. Russell Johnson, aka the Professor, plays the real estate agent who sells the Thrashers the haunted house in “The Hungry Glass,” and Natalie Schafer, best remembered as Lovey Howell, plays the dotty novelist in “The Grim Reaper.”

Judgment at Nuremberg (1961)

By the late 1950s, Shatner was hearing the same line over and over again. “At that point in my career it seemed like every phone call I got from a movie director or a TV producer or an agent began with the statement, ‘Bill, honestly this [fill in the blank] is the one that’s going to make you a star,’” Shatner wrote in Up Till Now. The first of Shatner’s supposedly star-making roles arrived in 1958, when he was cast opposite Yul Brynner, Richard Basehart, and Lee J. Cobb in director Richard Brooks’s high-profile adaptation of Dostoyevsky’s The Brothers Karamazov. Shatner played the youngest brother, Alexi (even though the actor later admitted that he couldn’t make heads nor tails of the book). Despite an ample budget, a fine cast, and an impressive literary pedigree, Brooks’s film was an artistic and commercial disappointment and did nothing to advance Shatner’s career.

A few years later came Judgment at Nuremberg, an important “message picture”—a courtroom drama about the Nazi war crimes trials—with a star-studded cast, directed by the respected Stanley Kramer (Inherit the Wind, On the Beach, etc.). Shatner was offered the role of a young army lawyer. His agent assured him this was the picture that would finally make him a star, but the actor also believed the project would keep the memory of the Holocaust alive to serve as a warning against similar atrocities. Judgment at Nuremberg was a box-office hit and a critical triumph. It racked up eleven Academy Award nominations and took home two Oscars, including Maximilian Schell as Best Actor. Spencer Tracy was also nominated as Best Actor, and Montgomery Clift and Judy Garland earned Supporting Actor and Actress nominations. Burt Lancaster, Richard Widmark, and Marlene Dietrich contributed memorable supporting performances. Lost in the shuffle, however, was Shatner. Although by his mere presence the actor brought some warmth and charm to his role, Captain Harrison Byers is a colorless, do-nothing character. He’s the guy who swears in the aging stars playing the witnesses in the trial, so they can give spectacular performances while Shatner sits at a table wearing a headset and scribbling in a notepad. His most dramatic dialogue is, “Raise your right hand.” Still, Shatner enjoyed making Judgment at Nuremberg. It was a noble endeavor, and it gave the young actor a chance to work alongside performers he had idolized, especially Tracy.

The Intruder (1962)

Nobody thought The Intruder would make Shatner a star, and it didn’t. But it should have.

Shatner is simply sensational as Adam Cramer, a carpetbagging demagogue who travels to a sleepy Southern town to inflame white resentment over the desegregation of the fictional Caxton High School. He hopes to stir up the locals’ fear and loathing and manufacture a racial incident that will discredit desegregation laws and the civil rights movement in general. The quick-witted, silver-tongued Cramer is reprehensible but riveting as he dupes and race-baits the white citizenry (including members of the Ku Klux Klan) into homicidal violence, including a church bombing. Along the way, he also seduces the depressed wife of a traveling salesman and the teenage daughter of the local newspaper editor. Ultimately, however, Cramer’s machinations spin out of control, and he is undone by his own dark ambitions. The entire film turns on Shatner’s subtle, oily portrayal of Cramer. His performance that suggests if he hadn’t later become a starship captain, Shatner might have made an excellent Ferengi.

Produced and directed by Roger Corman and written by frequent Twilight Zone scribe Charles Beaumont, The Intruder remains a powerful viewing experience, uncommonly frank and uncompromising for its era. (For instance, whites use the word “nigger” with now-shocking casualness and frequency.) But the picture was a bit too powerful in its day. Although it won a special citation at the Venice Film Festival and performed well in other international exhibitions, Corman had great difficulty distributing The Intruder in the U.S. The drive-ins and exploitation houses that played his usual B-movies wouldn’t touch it, and Corman did not yet have the critical cachet to earn many art house bookings. Naturally, the film was virtually impossible to sell in the South. As a result The Intruder became the first (and for many years only) Corman production to lose money.

It’s a wonder the film was made at all. Shatner’s and Corman’s autobiographies both feature jaw-dropping stories about the movie’s production. Shot on location in Mississippi County, southeast Missouri, The Intruder required careful subterfuge (few locals saw the real script or had any idea what the film was truly about). Despite these precautions, however, enough of the story leaked to agitate area bigots, and the cast and crew operated under constant threat of physical violence. The film’s provocative cross-burning scene was the last footage shot—afterward, the entire company packed up and drove hundreds of miles north, where they could sleep safely. Despite the fact that it lost money, Corman routinely names The Intruder as his personal favorite among the nearly 400 films he has produced. Shatner is also justifiably proud of the picture. But since nobody saw it, it did little for his career.

The Twilight Zone Episode “Nightmare at 20,000 Feet” (1963)

William Shatner first entered The Twilight Zone on November 18, 1960, with the broadcast of “Nick of Time,” an episode about a honeymooning couple whose car breaks down in small-town Ohio. While waiting for repairs, Don (Shatner) and Pat (Patricia Breslin) drop into a local diner for lunch and discover a penny fortune-telling machine in their booth. The newlyweds are amazed to discover that the mechanical “Mystic Seer” actually can predict the future. Superstitious Don, who carries a rabbit’s foot and a four-leaf clover keychain, quickly becomes fascinated, even fixated, on the machine, but Pat fears it—and the influence it’s exerting on her husband. “Nick of Time,” broadcast the week after one of the Zone’s best-remembered episodes (“In the Eye of the Beholder”) midway through the show’s second season, is a subtle, thought-provoking yarn written by the famed Richard Matheson. Shatner and Breslin both give warm, endearing performances as the just-married couple discovering each other’s strengths and weaknesses and learning how to forge their path together. All in all, it’s a very good show.

But Shatner was seen to far greater advantage when he returned to the series for “Nightmare at 20,000 Feet,” revered as one of the greatest (not to mention scariest) of all Zone episodes. Broadcast October 11, 1963, during the series’ fifth season, the story—again by Matheson—features Shatner as Bob Wilson, a high-strung salesman flying home to his family after recovering at a sanitarium from a nervous breakdown. As the plane flies through the stormy night sky, Wilson spots a furry little man—a gremlin—on the wing, attempting to sabotage the engine. But since the creature hides whenever anyone other than Wilson looks out the window, no one believes him. Instead, they assume the salesman’s mind is going again. Increasingly agitated and frightened, Wilson decides he must defeat the gremlin himself, even if doing so lands him back in the sanitarium. “Nightmare at 20,000 Feet” is twenty-five minutes of perfectly constructed white-knuckle suspense. Matheson, adapting from his own short story, improves upon the original by giving Wilson a wife and other characters to talk to, externalizing the character’s thought process. But Shatner’s face registers all the emotion necessary to convince viewers of the terror of the scenario—disbelief, fear, frustration, anger, despair, and finally determination and relief. It’s a masterful performance, among the finest of his career.

In this publicity still, William Shatner hams it up with the gremlin that tormented him during the classic Twilight Zone episode “Nightmare at 20,000 Feet.”

One of the best loved of all Twilight Zone episodes, “Nightmare at 20,000 Feet” was also among the four classic episodes recreated for the 1993 big-screen Twilight Zone: The Movie, with John Lithgow in the Bob Wilson role. Years later, when Shatner took on a recurring featured role in Lithgow’s sitcom, 3rd Rock from the Sun, about a family of aliens living incognito among humankind, the show’s writers couldn’t resist an inside joke based on the two actors’ Twilight Zone connection. In his first 3rd Rock scene, Shatner, playing Lithgow’s boss (known as the Big Giant Head), has just arrived from “out of town.” Lithgow asks if he had a good flight. “It was horrible,” Shatner replies. “I looked out and saw something on the wing of the plane.” Lithgow, incredulous, exclaims, “The same thing happened to me!”

The Outer Limits : Episode “Cold Hands, Warm Heart” (1964)

Shatner delivered another tour de force performance in The Outer Limits episode “Cold Hands, Warm Heart.” Astronaut Jefferson Barton (Shatner) returns to a hero’s welcome after becoming the first man to orbit the planet Venus. But he’s puzzled by an eight-minute blackout he suffered while orbiting the planet and plagued by strange nightmares and an inability to keep warm (even with the furnace turned up to eighty-five, he wears a sweater and gulps down hot coffee). Since he’s supposed to pilot an upcoming mission to Mars (prophetically titled Project Vulcan), he tries to hide his condition from both military doctors and his beloved wife (Geraldine Brooks). But then his hands begin turning into scaly claws …

Many critics and fans consider The Outer Limits the best science fiction TV show ever made, but it was not financially successful at the time. “Cold Hands, Warm Heart” was the second episode broadcast during the program’s second season, but only fifteen more would air before ABC cancelled the series, which at the time suffered in frequent comparisons with CBS’ The Twilight Zone. While only forty-nine episodes of The Outer Limits were produced, most of those are now treasured as classics. “Cold Hands, Warm Heart” isn’t one of the series’ finest episodes—like the offbeat “Zanti Misfits,” about a gang of ant-like alien criminals, or writer Harlan Ellison’s hard-hitting “Soldier,” which inspired director James Cameron’s The Terminator—but it’s a solid entry and one that, like “The Hungry Glass” and “Nightmare at 20,000 Feet,” depends entirely on the actor’s performance to carry the tale. The script offered Shatner several well-written romantic interludes in addition to the suspenseful, at times even horrific, primary story line.

For the People (1965)

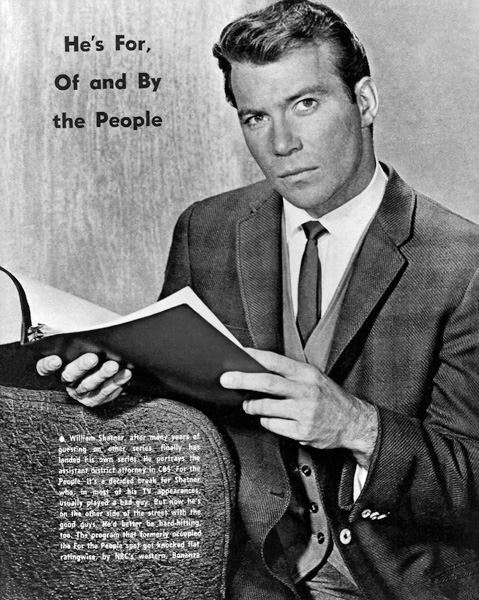

Eight years after he declined to star in The Defenders, Shatner accepted the lead in another weekly courtroom drama, producer Herb Brodkin’s For the People. Shatner starred as Assistant District Attorney David Koster, an ambitious young prosecutor trying to balance his passion for his job against the demands of his marriage to a free-thinking professional viola player, Phyllis (Jessica Walter). The cast also featured Howard Da Silva as Koster’s boss and Anthony Celeste as police detective Frank Malloy. The show—which in certain respects anticipated the long-running NBC series Law & Order—was praised by critics but lasted just thirteen episodes because CBS slotted it opposite the top-rated program on television, ABC’s Western powerhouse Bonanza. “Test patterns had better time spots,” Shatner wrote in his autobiography. “For the People never had a chance.”

But at least it was picked up by the network, which was more than could be said for the first series in which Shatner agreed to star. In 1963, he had played the title role in the two-hour pilot film Alexander the Great. Envisioned by producer Selig J. Seligman (who had created the hit series Combat!) as a weekly costume drama based on the adventures of one of history’s fabled military commanders, the show promised lots of horseback chase sequences, sword fights, and scantily clad women. Shot in Utah on a tiny budget, the telefilm was directed by Phil Karlson (whose filmography includes the noir gem Kansas City Confidential [1955] and the later cult classic Walking Tall [1973]) and costarred John Cassavetes, Joseph Cotten, Simon Oakland, and a pre-Batman Adam West. Despite this astounding cast, Seligman was unable to find a taker for his unusual series. Alexander the Great belatedly aired as a movie-of-the-week in January 1968.

Magazine ad for Shatner’s short-lived legal drama For the People, in which he played a young prosecuting attorney with a complicated personal life.

In retrospect, the failure of his two previous TV shows was a disguised blessing. If CBS had given For the People a more favorable time slot, Shatner may not have been available when Star Trek producer-creator Gene Roddenberry went looking for replacement starship captains in the spring of 1965. Then fans may have been stuck with someone like Jack Lord as Captain Kirk. But that’s another chapter.

Incubus (1966)

In most respects, writer-director Leslie Stevens’s Incubus is a fairly typical low-budget horror film. In fact, with an overtly symbolic, Bergmanesque storyline and cinematographer Conrad Hall’s German Expressionist-influenced lighting schemes, it’s smarter and better crafted than most other movies of its stripe. But that’s not why Incubus is remembered. It’s famous—or perhaps infamous—because Stevens shot the film in Esperanto, the “global language” invented by Russian philologist L. L. Zamenhof. In 1887, Zamenhof published the first textbook for Esperanto, which he hoped would eventually serve as a universal second language and help promote understanding between people from different nations and ethnic backgrounds. Stevens, creator of The Outer Limits, shared Zamenhof’s idealism and wanted to promote use of the language.

Incubus is the story of a demon named Kia (Allyson Ames), a succubus who lures sinners to their doom and claims their souls for Satan. But she’s bored with preying on the weak-willed and black-hearted. Looking for a greater challenge, she decides to try to seduce and destroy the saintly Marc (Shatner), a devoutly Christian war hero. To her surprise, Marc falls in love with her, refusing a simple tryst and insisting on a church wedding; the story becomes a battle of wills between Marc’s pure love and Kia’s inveterate evil.

When William Shatner signed to play the lead in the film, he didn’t know it would be shot in Esperanto. The script was written in English, so the actor naturally assumed it would be performed in that language. Nevertheless, Stevens won Shatner over with his enthusiasm for the idea of shooting in Esperanto. Since none of the cast spoke Esperanto, they were all shipped out for an intensive, two-week training on the language and its proper pronunciation (despite which, the same words are pronounced completely differently by various members of the cast). Stevens directed in Esperanto, or tried to. Shatner first saw the film at an international film festival, where it was subtitled in Italian. Since he didn’t speak Italian, and had long since forgotten his limited Esperanto, he found the experience incomprehensible. So did most other viewers wherever the film was shown—which wasn’t many places. Incubus played a few film festivals in the U.S. and received general release only in France.

Filmed in May 1965, after the cancellation of The Outer Limits, Incubus wasn’t issued anywhere until 1966. By then, Shatner had taken on a new role, the one that really would (eventually) make him a star: Captain James T. Kirk of the starship Enterprise.