9

Roads Not Taken to the Second Star Trek Pilot

In July 1965, Star Trek boldly went where no show had gone before: back into pilot.

Ordinarily, when a series fails to sell, the project is consigned to oblivion. But NBC executives were impressed enough with “The Cage,” Star Trek’s rejected original telefilm, that they took the unprecedented step of ordering a second pilot rather than abandoning the concept. While this presented an extraordinary second chance, producer Gene Roddenberry and his creative team understood this was also the series’ final chance. After investing $450,000 in “The Cage” (Desilu Productions kicked in an extra $164,000 to cover overruns), NBC agreed to sink another $300,000 in a second, as yet untitled, pilot, making this an extremely expensive do-over. If the network remained unsatisfied with this second attempt, Star Trek would be scrapped and NBC would write off a princely three quarters of a million dollars in development funds ($5.4 million in inflation-adjusted figures).

With its money on the line, the network demanded major changes to the cast, characters, and overall tone of the show. To meet NBC’s expectations, Roddenberry would have to reshape and, in some aspects, reimagine the program. Along the way, he and his team would have to choose wisely from various options as they made pivotal decisions regarding the show’s content and cast. The Star Trek story might have had a very different ending if this second pilot had been “The Omega Glory,” starring Jack Lord as Captain January, leader of a Spock-less starship Enterprise. Here are the key issues Roddenberry and company faced at this delicate stage of the program’s development, the decisions they made, and the alternatives they discarded.

Rejected Teleplays

The first order of business was to devise a storyline for the second pilot. NBC wanted a show that packed more action than “The Cage,” which executives considered too static and “cerebral.” They also wanted Roddenberry to tone down the sexual content of the show. Three potential pilot teleplays were written, which Roddenberry supplied to NBC for consideration.

From those, the network selected screenwriter Samuel Peeples’s “Where No Man Has Gone Before.” In this episode, Enterprise helmsman Gary Mitchell accidentally gains superhuman telepathic and telekinetic abilities after the ship encounters a mysterious energy barrier at the edge of the galaxy. Mitchell, a Starfleet Academy classmate of Kirk’s, becomes imperious and unstable as his powers increase, posing a danger to the Enterprise. Forced to choose between his ship and his friend, and acting on advice from Spock, Kirk decides to strand Mitchell on a distant planet—but Mitchell, whose powers are now approaching the godlike, resists. Appropriately, since Roddenberry had sold NBC on Star Trek by describing the show as an outer space Western, at the time Peeples was best known as the author of several popular Western novels, written under the pen name Brad Ward. His teleplay “Where No Man Has Gone Before” featured a tension-packed scenario, rich in both interpersonal drama and bare-knuckled action scenes. It proved to be an ideal choice for a pilot episode.

The other two teleplays Roddenberry sent to NBC might not have worked so well. They were:

“The Omega Glory”—Captain Kirk, Mr. Spock, and Dr. McCoy beam down to Omega IV, a planet reduced to barbarism by a centuries-old war between factions known as the “Kahms” and the “Yangs.” The situation is complicated by the presence of Captain Ronald Tracey of the starship Exeter, who, after being stranded on the planet, has provided military aid to the Kahms in blatant violation of the Prime Directive. Kirk eventually realizes that Omega IV is a parallel Earth and that the ancient conflict is the Cold War between East (the name “Kahms” derived from Communists) and West (“Yangs” = Yankees). Although written by Roddenberry himself, this remains one of the most improbable and heavy-handed of all Star Trek stories. Not only was “The Omega Glory” passed over as a potential pilot, but it lingered on the shelf until late in Season Two, even though the show remained desperate for usable teleplays throughout its first season. It finally aired March 1, 1968.

“Mudd’s Women”—This humorous episode features Harcourt Fenton Mudd, an interstellar con man who provides gorgeous wives to lonely space settlers—until Kirk discovers that Mudd’s women owe their beauty thanks to regular doses of an illegal drug. Written by Stephen Kandel from a story by Roddenberry, “Mudd’s Women” would become a fan favorite. It introduced the recurring character of Harry Mudd (played by Roger C. Carmel), a likeable scoundrel who would exasperate the Enterprise crew in two classic Trek episodes and an installment of the animated series. Nevertheless, the story was too lighthearted and too racy to satisfy NBC as a pilot. Instead, it became the second regular episode of the show produced and the sixth one to air, running October 13, 1966.

Captains Who Abandoned Ship

While Roddenberry struggled to develop a teleplay that would meet NBC’s demands, Star Trek was dealt another serious blow: Jeffrey Hunter wanted out. Hunter, who had starred in “The Cage” as Captain Christopher Pike, was under contract to appear in the series if the original pilot sold but not to appear in the unforeseen second pilot. The actor was unhappy with “The Cage” and ambivalent about moving out of feature films and into a full-time job on television. The show’s leadership had no recourse other than to let him go, leaving Star Trek without a star. Selecting Hunter had been a long and arduous process. Among the forty names submitted for the role by one casting consultant were Hunter, Lloyd Bridges, Nick Adams, Cameron Mitchell, Peter Graves, Rod Taylor, Sterling Hayden, Robert Stack, George Segal, Jack Lord, and William Shatner. This list was eventually whittled down to a group of five that included James Coburn in addition to Hunter. NBC asked Roddenberry to consider Patrick McGoohan and Mel Ferrer, but neither were serious candidates. Now, with Hunter out of the picture, Roddenberry, Desilu production chief Herb Solow, and casting director Joe D’Agosta went back to their forty-name original list and reconsidered their options.

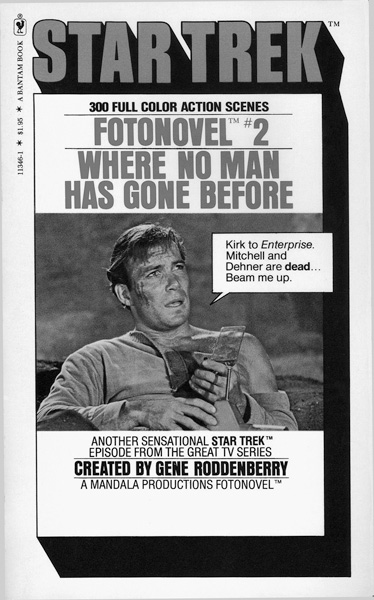

In 1977, Bantam Books adapted Star Trek’s second pilot, “Where No Man Has Gone Before,” as a comic book–like “Fotonovel.”

The team settled on Jack Lord as their top choice. Lord (the stage name of actor John Joseph Patrick Ryan) had appeared in more than a dozen films and guest starred on scores of television series but, in 1965, was best recognized for his turn as CIA agent Felix Leiter in the first James Bond film, Dr. No (1962). Roddenberry offered the captaincy of the starship Enterprise to Lord but balked when the actor asked to produce as well as star and demanded an astronomical 50 percent profit participation in the program. Roddenberry moved on, and so did Lord. In 1968, the actor agreed to star in TV’s Hawaii Five-O, which ran for twelve seasons and 279 episodes (200 more than Trek). For appearing as Detective Steve McGarrett—whose signature catchphrase “Book ’em, Danno” quickly entered the popular vernacular—Lord received one-third profit participation. When series creator Leonard Freeman died in 1974, Lord took over as executive producer and gained complete creative control over the series.

After scratching Lord’s name off his list, Roddenberry turned to a Canadian actor with a résumé not dissimilar to Lord’s—William Shatner. Shatner was stinging from the midseason cancellation of his first television series, the courtroom drama For the People. Despite the failure of that program, Shatner remained recognizable to TV viewers as a frequent guest star on other shows—by 1965, he had racked up appearances on forty-five television series, some on multiple occasions, not counting appearances on stage and in feature films. Casting director D’Agosta told Roddenberry biographer David Alexander that in 1965 Shatner “had the same thrust going for him that Clint Eastwood and Steve McQueen did.” Clearly, Shatner would be the show’s star (or so he thought), and his agent negotiated a star’s contract. Shatner received a salary of $5,000 per week plus 20 percent of that salary for the first five reruns of each episode, as well as 20 percent profit participation. He was an inspired choice to play Trek’s new starship captain. His zesty, upbeat approach to the role helped supply the energy boost NBC felt the program needed.

Discarded Names for the Captain of the Enterprise

With Shatner stepping in for Hunter, Roddenberry felt the character needed a new name. Already the captain’s name had changed multiple times. In his initial proposal, Roddenberry had named the captain Robert T. April. For a while he considered the names Captain Winter or even Captain Gulliver. In “The Cage,” Hunter had portrayed Captain Christopher Pike. A memo Roddenberry sent to the Desilu research department sought legal clearance for fifteen possible new names for the captain of the Enterprise. According to the list, reprinted in Herb Solow and Robert Justman’s Inside Star Trek, the ship might have been led by any of the following captains: January, Flagg, Drake, Christopher, Thorpe, Richard, Patrick, Raintree, Boone, Hudson, Timber, Hamilton, Hannibal, Neville, or (last on the list) Kirk. As an afterthought, Roddenberry scrawled a sixteenth name, “North,” at the bottom of the list in all-capital letters. Roddenberry finally chose “Kirk” simply because he liked the sound of the name. This was another good call. Somehow, Captain Kirk rolls off the tongue better than Captain Timber or Captain Neville.

Decommissioned and Short-Tenured Crew Members

Not only was Captain Pike replaced for the second Star Trek pilot, but so was nearly his entire crew. Ironically, although the network was satisfied with Hunter, it wanted most of the other roles recast. John Hoyt as Dr. Boyce, Laurel Goodwin as Yeoman Colt and Peter Duryea as Lieutenant Tyler were out. NBC also demanded that two characters—First Officer Number One (played by Majel Barrett) and Second Lieutenant Mr. Spock (Leonard Nimoy)—be eliminated entirely. NBC’s marketing research indicated that Spock’s satanic appearance might make the program difficult to sell in the Bible belt. Roddenberry reluctantly agreed to eliminate Number One but, despite intense pressure to meet the network’s demands, refused to jettison the Vulcan, making it clear that there would be no Star Trek without Spock. The presence of a nonhuman crew member was integral to the concept of the show, he argued. Eventually, NBC acquiesced and the character remained on board.

However, First Officer Spock of “Where No Man Has Gone Before” would be very different from the smiling, curious second lieutenant Spock of “The Cage.” Roddenberry not only promoted the Vulcan to second-in-command (giving him a more prominent role in storylines) but gave him Number One’s cool, computer-like personality as well. Curiously, since NBC objected primarily to the character’s physical appearance, Roddenberry never entertained the possibility of changing Nimoy’s makeup to something less threatening. Retaining Spock would prove to be perhaps the best of all the choices Roddenberry made at this time. The (admittedly limited) success Star Trek enjoyed during its original network run grew in large part from the audience’s fascination with Mr. Spock and the logic-driven Vulcan culture.

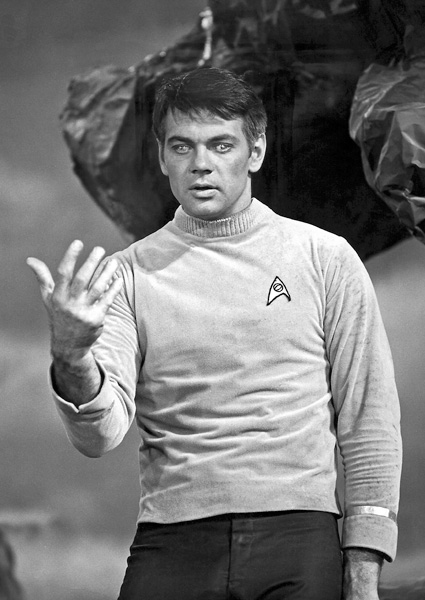

Careful consideration was given to the show’s guest stars, since helmsman Gary Mitchell and psychologist Elizabeth Dehner were the most prominent characters in Peeples’s teleplay other than Kirk and Spock. Roddenberry brought in Gary Lockwood, star of his first series, The Lieutenant, to appear as the doomed Mitchell. To play Dr. Dehner, he hired Sally Kellerman, who would earn an Oscar nomination as Best Supporting Actress for her performance as Margaret “Hot Lips” Houlihan in director Robert Altman’s 1970 blockbuster M*A*S*H. Both Lockwood and Kellerman contributed excellent performances to “Where No Man Has Gone Before,” even though they were forced to perform in painful, silver-colored hard contact lenses.

With Lockwood and Kellerman on board, all that remained was filling out the rest of Captain Kirk’s crew. Perhaps emboldened by a memo from NBC programming chief Mort Werner encouraging Roddenberry to hire minority (especially “negro”) actors (another document reprinted in Inside Star Trek), the Great Bird of the Galaxy this time selected an ethnically diverse bridge crew for the starship Enterprise, including Japanese American George Takei as physicist (not yet helmsman) Sulu and African American Lloyd Haynes as communications specialist Alden. Both of these parts were newly created for the pilot, as was a third role: chief engineer Montgomery Scott, played by Canadian James Doohan. Fresh-faced ingénue Andrea Dromm signed on to play Yeoman Smith, while Hollywood veteran Paul Fix was hired to play Dr. Piper.

While Takei and Doohan would become forever identified with Sulu and Scotty, none of the other cast members stuck. Once the series finally received the green light, Star Trek underwent another round of recasting. Haynes, given virtually nothing to do in “Where No Man Has Gone Before,” was replaced by Nichelle Nichols as Lieutenant Uhura. Haynes went on to costar in writer-producer James L. Brooks’s acclaimed comedy-drama series Room 222 from 1969 to 1974. Dromm, who enjoyed a meteoric rise to fame playing a perky flight attendant in an airline commercial, left no impression whatsoever as Yeoman Smith. Grace Lee Whitney was hired to step in as Yeoman Janice Rand, while Dromm landed only one more screen role, in the forgettable Troy Donahue comedy-mystery Come Spy with Me (1967). Fix’s gruff Dr. Piper was overshadowed in “Where No Man Has Gone Before” by Kellerman’s Dr. Dehner. He was replaced by DeForest Kelley as Dr. Leonard “Bones” McCoy. Fix’s career, which began in the silent era, continued into the early 1980s. He played supporting roles in well over a hundred movies and TV shows, appearing most memorably as Judge Taylor in To Kill a Mockingbird (1962).

The Jettisoned Original Version

The second Star Trek pilot went into production July 20, 1965, and wrapped eight days later, one day over schedule and $30,000 over budget (once again, Desilu made up the difference). But postproduction dragged on for ten months, partly due to delays in completing its special visual effects and partly because Roddenberry was also finishing the Police Story pilot. NBC finally received “Where No Man Has Gone Before” in January 1966. It took a month for the network to render its verdict. Despite a disastrous test screening, NBC decided to move forward with Star Trek and informed Desilu that the program would appear on the network’s fall schedule. Even though half the Enterprise crew was subsequently replaced, and even though the show’s costumes and props were more like those from “The Cage” than those seen in later episodes, “Where No Man Has Gone Before” was considered usable as a regular installment of the series. It became the third episode broadcast, airing on September 22, 1966.

“Where No Man Has Gone Before” guest starred Gary Lockwood, who had played the title role in Gene Roddenberry’s previous series, The Lieutenant. A few years later, Lockwood would portray astronaut Frank Poole, who is murdered by the HAL-9000 computer in 2001: A Space Odyssey.

However, the broadcast version differed noticeably from the pilot approved by NBC executives. The original version of “Where No Man Has Gone Before” had a unique title sequence, different musical cues, and featured on-screen titles designed to follow commercial breaks (announcing “Act I,” “Act II,” and so on) in the style popularized by producer Quinn Martin with hits like The Fugitive. The original “Where No Man Has Gone Before” also included nearly five minutes of additional footage that had to be trimmed to get the episode to the then-standard fifty-minute broadcast length (allowing time for commercials). For many years this original version was believed lost, but a print surfaced in Germany in 2009 and was included as a bonus feature on Star Trek: The Original Series—Season Three Blu-ray collection. As of this writing (in the fall of 2011), it has never aired on television. However, it was shown at the WorldCon science fiction convention in Cleveland, Ohio, in September 1966, where Roddenberry first unveiled his soon-to-premiere series to genre fans and insiders. It earned a standing ovation.