10

Laying the Foundation

From the very beginning, Star Trek was a remarkable program, daring in both format and content. But it took a while for the show’s writing and production capabilities to catch up with its ambitions, and for the cast to get a handle on their characters. Throughout its first season, despite many intimidating obstacles, the series slowly came together. During the spring, summer, and fall of 1966, creator-producer Gene Roddenberry assembled a gifted team of writers, directors, technicians, and artisans. Once everyone was in place, the show ascended to a new level of excellence. Along the way, the building blocks of Star Trek mythology fell into place. In the end, the zealous efforts of the show’s cast and crew were rewarded with an Emmy nomination for Best Dramatic Series and, most importantly, a renewal by NBC. The following milestones mark the series’ first-season maturation.

April 27, 1966: Dorothy Fontana Submits Her Treatment for “Charlie X”

Initially, the biggest problem facing Roddenberry, associate producer Bob Justman, and script consultant John D. F. Black was a dearth of filmable stories. Star Trek was unattractive to most established screenwriters, who had little interest in science fiction and who feared the offbeat show wouldn’t survive long enough for their teleplays to be produced, or to earn additional royalties through reruns. To fill this creative void, and to shore up the program’s sci-fi credentials, Roddenberry invited high-profile authors such as Theodore Sturgeon, Harlan Ellison, Robert Bloch, Richard Matheson, Jerry Sohl, Jerome Bixby, and George Clayton Johnson to write for the show. A handful of these luminaries (including Ellison, Bloch, and Matheson) had experience writing for TV, but most did not, and turning their ideas into episodes often required long and arduous rewrites. Some SF authors invited to write for Trek, including the legendary A. E. van Vogt, never devised a workable concept at all.

Fledgling screenwriter Dorothy Fontana was working as Roddenberry’s secretary when he asked her to pen the Star Trek Writers Guide (commonly referred to as the show’s “Bible”), which summarized the series’ characters, setting, and core concepts for prospective screenwriters. Impressed by her work, Roddenberry assigned Fontana to develop a script based on his outline for a story called “Charlie Is God.” Fontana’s treatment, retitled “Charlie X,” marked her first contribution to a Trek teleplay. Three drafts later, the script was ready to shoot. “Charlie X,” filmed July 12–19 and aired September 14, emerged as one of the best of the show’s early installments. Under the gender-neutral byline D. C. Fontana, she went on to write nine more episodes, including the landmarks “Journey to Babel” and “The Enterprise Incident.” When Black left the show midway through Season One, Fontana took over as story editor, a position she retained until the conclusion of Season Two. In that capacity she provided uncredited polishes on twenty-six teleplays. Fontana, whose tenure as story editor coincided with the show’s creative peak, became a mainstay of Star Trek’s original incarnation, as well as of the later animated series and the first season of The Next Generation.

May 24, 1966: Shooting of “The Corbomite Maneuver” Begins, with DeForest Kelley, Nichelle Nichols, and Grace Lee Whitney

“The Corbomite Maneuver,” the first regular episode of the series produced, also featured the debuts of DeForest Kelley as Dr. McCoy, Nichelle Nichols as Lieutenant Uhura, and Grace Lee Whitney as Yeoman Rand.

Roddenberry transferred Kelley to the Enterprise when another pilot, Police Story, failed to sell. It was the producer’s second failed attempt to create a series for Kelley, following the stillborn legal drama 333 Montgomery in 1964. The actor’s fine work as Leonard “Bones” McCoy rewarded Roddenberry’s loyalty. Kelley’s warmth, humor, and compassion helped humanize Star Trek, making the show seem almost homey despite all the futuristic gadgetry and alien settings. And his rapport with costars William Shatner and Leonard Nimoy provided the secret ingredient in the Kirk-Spock-McCoy chemistry. Kelley excelled in both McCoy’s sympathetic heart-to-hearts with Kirk and his (usually) comedic verbal jousts with Spock. Writers enjoyed writing for Kelley and gave his character little quirks (like the doctor’s loathing of the transporter device) that were fun to play and further endeared McCoy to audiences. Although Kelley’s contract didn’t guarantee him work in every episode, McCoy failed to appear in just three installments throughout the next three seasons: “What Are Little Girls Made Of?” “The Menagerie, Part II,” and “Errand of Mercy.”

At first, Nichols, a former guest star on Roddenberry’s The Lieutenant (and an ex-girlfriend of the producer), was given nothing much to do other than sit in a chair on the bridge and announce, “Hailing frequencies open, Captain.” Eventually, however, writers began to flesh out Uhura and occasionally gave Nichols the opportunity to demonstrate her lovely singing voice. Even when her role seemed robotic and thankless, however, Nichols—by her mere presence—delivered a powerful statement. Star Trek premiered in the thick of African Americans’ struggle for civil rights. The sight of a black woman in a leadership position on the flagship of the Federation inspired numberless young people of color.

Whitney, another Police Story refugee, was featured prominently in the show’s early publicity. A sexy female yeoman had been part of Roddenberry’s original outline for Star Trek, and other young, blonde, female yeomen had appeared in the two pilots. Yet Janice Rand failed to develop as a character. Whitney left the show under controversial circumstances four months later, after appearing in just eight episodes.

“The Corbomite Maneuver” also remains notable as the first episode with George Takei’s Lieutenant Sulu at the helm of the Enterprise. Takei had appeared in the second pilot, “Where No Man Has Gone Before,” but Sulu had a less prominent assignment as a blue-shirted physicist. Designer Bill Theiss’s iconic “redshirt” uniforms also debut here, although the gold-blue-red color designations (correlating to command, science, and operational functions) was not yet established, as evidenced by Uhura’s appearance in a gold minidress rather than her usual red.

June 3–13, 1966: Cyclorama Introduced During Production of “Mudd’s Women”

“Mudd’s Women,” the second episode produced for Season One, marked several firsts, including Roger C. Carmel’s bow as planet-hopping flimflam artist Harry Mudd. Also making its first appearance in this episode was the soundstage cyclorama that, with strategic employment of red and yellow gels, created the pink-orange sky of planet Rigel XII. Production designer Matt Jefferies and cinematographer Jerry Finnerman reused the cyclorama, lit with gels of various colors, to generate skies for all the many planets Captain Kirk and crew visited—except those rare adventures shot on location. The cyclorama was typical of Jefferies’s elegant and ingenious solutions, which helped maximize the show’s modest construction budget. Except for the bridge, every Enterprise set pulled double or triple duty: the briefing room was redressed for use as the commissary, the recreation room, and numerous other spaces; the engine room doubled as the shuttle bay; and the same cabin set was shared by everyone—Kirk, Spock, and passengers alike.

June 23: Marc Daniels Begins Directing “The Man Trap”

Marc Daniels directed more episodes of Star Trek than anyone else—fifteen in all, including classics like “Space Seed,” “The Doomsday Machine,” and “Mirror, Mirror.” But his most important contribution to the show’s success may have occurred while the cameras were turned off. During the shooting of “The Man Trap,” Daniels set up a folding table adjacent to the soundstage. While sets were dressed and lights were rigged, he sat at the table with the cast and ran lines for the upcoming scenes. As a result, actors’ performances improved and filming required fewer takes. Daniels, coincidentally, was scheduled to helm the next episode as well, so the table—and the read-throughs—remained in place throughout production of “The Naked Time,” from July 1 through July 11. By the time Larry Dobkin arrived to direct “Charlie X” on July 12, the show’s “table rehearsals” had become a fixture. They would continue until the final episode, “Turnabout Intruder,” which wrapped on January 9, 1969. Directors came and went, but the cast remained committed to working together between setups rather than retreating to their dressing rooms, as was common on most series. Guest stars were also expected to participate. These informal rehearsals were especially important during the show’s first season because revised pages arrived on the set daily. Roddenberry often worked until the wee hours of the morning, sometimes pulling amphetamine-powered all-nighters, polishing dialogue or reworking scenes. His efforts, combined with the dedication of the cast and directors like Daniels, resulted in a better written, more convincingly performed, and more efficiently produced program.

July 1–11, 1966: Nurse Chapel Debuts in “The Naked Time”

Adding Majel Barrett to the cast as Nurse Chapel provided DeForest Kelley with a counterpart to share scenes with. This, in turn, helped writers expand Dr. McCoy from a supporting character to the show’s third lead.

“The Naked Time,” written by John D. F. Black and directed by Marc Daniels, was another key early episode. By introducing Majel Barrett as Christine Chapel, it completed the show’s legendary cast of characters. Roddenberry, who was carrying on an affair with Barrett, had been searching for an opportunity to bring the actress back aboard the Enterprise ever since her “Number One” character was axed (by network demand) following “The Cage.” He created Chapel for her, but the nurse’s presence was as big a boon to DeForest Kelley as to Barrett. Nurse Chapel provided a colleague for Dr. McCoy to share scenes with as writers continued to expand Kelley’s role. Although hired as a supporting player, Kelley was rapidly becoming the show’s third lead.

“The Naked Time,” the seventh episode produced and the fourth one broadcast, became the first story to focus on the show’s supporting characters. In it, the crew of the Enterprise falls prey to an alien infection that compels them to act out repressed feelings and desires: Sulu takes up a fencing foil and bounces around like one of the Three Musketeers; Spock hides away and cries. “The Naked Time” not only introduces Chapel but establishes the nurse’s unrequited romantic interest in Spock. The character would continue to serve as an on-again, off-again source of sexual tension for the Vulcan. This episode, along with Richard Matheson’s “The Enemy Within,” served as guideposts for future screenwriters as they fleshed out the personalities and backstories of the Enterprise crew.

Chapel also featured conspicuously in her next appearance, “What Are Little Girls Made Of?,” but soon fell into line with the rest of the supporting characters, stepping forward only occasionally for isolated moments during “Journey to Babel,” “Return to Tomorrow,” and a handful of other installments.

Late August 1966: Welcome Aboard, Gene Coon

Gene L. Coon, who replaced Roddenberry as the show’s line producer three months into its maiden voyage, was exactly what Star Trek needed. He was a capable producer whose steady hand ensured that the series didn’t miss a beat in production efficiency, while enabling Roddenberry to focus more on story development. Coon also wrote or cowrote eight episodes during his tenure as producer, including the classics “The Devil in the Dark,” “Space Seed,” and “Errand of Mercy,” and is credited with introducing the Klingons, the Prime Directive, the villainous Khan Noonien Singh and warp drive inventor Zefram Cochrane, among other building blocks of Trek mythology. Perhaps best of all, given the program’s continued stress to meet its airdates, Coon was also an astonishingly fast writer. Reportedly, he penned “The Devil in the Dark” from start to finish in four days. He also mentored young writers like David Gerrold, who he encouraged and guided through the creation of “The Trouble with Tribbles.” In all, Coon oversaw the production of thirty-one episodes, including many of the series’ finest installments. With his arrival, the final piece of the creative puzzle clicked into place.

September, 1966: The Curious Case of Janice Rand

Whitney’s Yeoman Rand made her final appearance in “The Conscience of the King,” the show’s thirteenth episode, produced in late September. Her last scene is a brief, nonspeaking walk-on. Rand would not be seen again for the remainder of the series and her departure would never be explained or even mentioned. The character was eliminated because, although Janice Rand was created to provide a source of romantic tension for Captain Kirk, writers believed that her presence was cramping Kirk’s Playboy-of-the-Galaxy style with the bevy of beautiful babes who beamed aboard each week. At least that’s always been the official version of events, and it’s a reasonable explanation.

However, the truth behind the departure of Grace Lee Whitney may be more complex. In her autobiography The Longest Trek, Whitney claims that on August 26, 1966, after the Friday night cast party for the previous episode (“Miri”), someone she refers to only as “The Executive”—but whom she describes as tall and “a womanizer”—sexually assaulted her in a Desilu meeting room following a bungled seduction attempt. She believes she was removed from the show as a result of this incident. In his book Star Trek Memories, Shatner provides Whitney’s account of the alleged assault but also reports that the actress’s behavior on the set had become erratic due to heavy drinking. In The Longest Trek, Whitney acknowledges being an alcoholic and diet pill addict during her tenure on the show but denies that this affected her performance. Her termination from Star Trek sent Whitney into a tailspin of addiction and other self-destructive behavior, but she gained sobriety in the 1980s and made cameo appearances as Rand in four of the Star Trek feature films (Star Trek: The Motion Picture, The Search for Spock, The Voyage Home, and The Undiscovered Country).

October 11–18: New Footage Created for “The Menagerie”

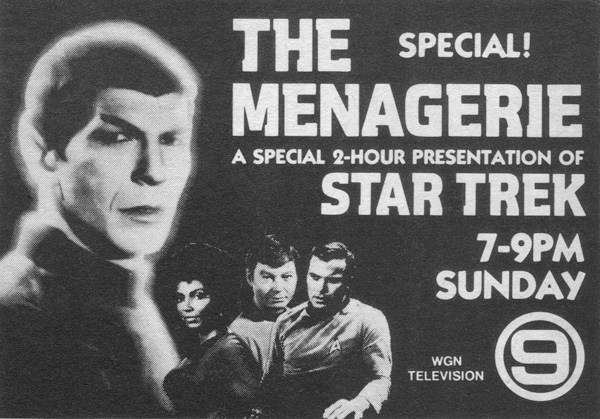

TV Guide ad for a special two-hour syndicated broadcast of “The Menagerie, Parts I and II” from the 1970s. This two-part adventure, which provided desperately needed breathing room in the show’s production schedule, remains one the series’ most beloved stories.

Despite the best efforts of the show’s writers, cast and crew, meeting airdates remained a week-to-week battle for Star Trek. To buy desperately needed breathing room in the production schedule, Roddenberry and his team decided to shoot new footage that could be combined with scenes from the scrapped original pilot, “The Cage,” to create a two-part epic. This would enable the program to fill two airdates but would require less than a week of original production. The plan meant scuttling Roddenberry’s original idea of expanding “The Cage” to feature length (by shooting the crash of the starship Columbia on Talos IV) and issuing the picture theatrically. The plan also presented some tricky writing problems, given the presence of Leonard Nimoy as a very different Spock in “The Cage” and Majel Barrett as both the brunette “Number One” and the blonde Nurse Chapel. The clever solution—having Spock commandeer the Enterprise to transport the grievously injured Captain Pike to Talos IV—was conceived by John D. F. Black, but his teleplay was heavily rewritten by Roddenberry, who received sole writing credit for the episode. Ace director Marc Daniels was engaged to shoot the new footage, which was skillfully integrated with judiciously edited material from “The Cage” to form “The Menagerie.”

The resulting two-part episode won a Hugo Award at the 1966 WorldCon and remains one of the series’ most enduringly popular tales. But the most important thing about this landmark adventure was that it alleviated some of the pressure on the Trek creative team. With a couple of fortuitous programming changes by NBC (Star Trek was preempted twice during its first season—for a Jack Benny holiday special Thanksgiving week and again for a Ringling Brothers Circus special in March) and one strategically deployed rerun (“What Are Little Girls Made Of?” was repeated December 22, just eight weeks after its initial broadcast), Star Trek met the remainder of its Season One airdates.

With increased flexibility in terms of deadlines and budgets came a significant uptick in quality. “The Menagerie, Parts I and II” aired November 17 and 24, 1966. Nearly all the thirteen episodes that followed during Season One were outstanding. This lineup of classics includes “Shore Leave,” “The Squire of Gothos,” “Arena,” “Tomorrow Is Yesterday,” “Return of the Archons,” “Space Seed,” “This Side of Paradise,” “The Devil in the Dark,” “Errand of Mercy,” and “The City on the Edge of Forever.”

September 8, 1966: Star Trek Premieres with “The Man Trap”

By the time Star Trek made its broadcast debut, several episodes had been completed. Which one to air first was a matter of considerable debate. “The Corbomite Maneuver,” the first episode produced, would have served as an ideal introduction but was nixed by NBC because it took place entirely aboard the Enterprise; the network preferred stories that involved travel to alien planets. “Charlie X” was ruled out for the same reason. Justman argued for “The Naked Time,” but it was also a “ship show” rather than a “planet show.” The second pilot, “Where No Man Has Gone Before,” was problematic because it didn’t include key cast members such as Kelley. And everyone agreed the comedic “Mudd’s Women” would give viewers a misleading impression of the series’ tone. Finally, NBC settled on “The Man Trap,” a rip-snorting sci-fi adventure complete with a murderous monster, the “Salt Vampire” of planet M-113.

Star Trek’s premiere earned middling ratings and unenthusiastic reviews. Weekly Variety’s critic ventured that the show was “better suited to the Saturday morning kidvid bloc” than prime time. NBC continued to air episodes in a haphazard order that made it difficult for viewers to follow the development of the show’s characters and its emerging mythology. “Charlie X,” produced eighth, aired second, followed by “Where No Man Has Gone Before” and “The Naked Time.” Although made first, “The Corbomite Maneuver” was broadcast tenth. When the show was syndicated in the 1970s, episodes were typically sequenced in production order.

February 2, 1967: Production Wraps on “Errand of Mercy”

This episode, written by Gene Coon and directed by John Newland, remains best known as the adventure that introduced the Klingons. But it’s also notable as the last episode in which Spock is referred to as a “Vulcanian.” Moving forward, persons from the planet Vulcan were referred to simply as Vulcans. Despite some nagging “Vulcanian”-like anomalies—in “Mudd’s Women,” for instance, the Enterprise engines rely on lithium (not dilithium) crystals—the show’s mythology had begun to cohere.

Although no one imagined that generations of fans would devote themselves to studying such minutiae, writers and producers nevertheless strived to ensure the continuity of the show’s setting, characters, and technology, meticulously crafting an integrated “future history” from week to week, teleplay by teleplay. By now, most of the foundational elements of the Star Trek universe were present, including the United Federation of Planets (named in “A Taste of Armageddon”) and its two main adversaries, the Romulans (introduced in “Balance of Terror”) and the Klingons. Also established:

• The names Starfleet and Starfleet Command entered the Trek lexicon with “Court Martial.” This episode also featured the Enterprise’s first trip to a star base.

• The frequently ignored Prime Directive was first explained in “The Return of the Archons.”

• The Vulcan neck pinch was first seen in “The Enemy Within,” and the mind meld was first witnessed in “Dagger of the Mind.”

• The Eugenics Wars and other future-historical events were introduced in “The Conscience of the King” and “Space Seed.”

• Photon torpedoes enter the arsenal of the Enterprise with “Arena.”

• The shuttlecraft and shuttle bay both debut with “The Galileo Seven.” (All the show’s shuttlecraft effects footage originates here, by the way. Whenever shuttles are seen in future episodes, it’s through the use of stock shots from The Galileo Seven, sometimes matted into different backgrounds.)

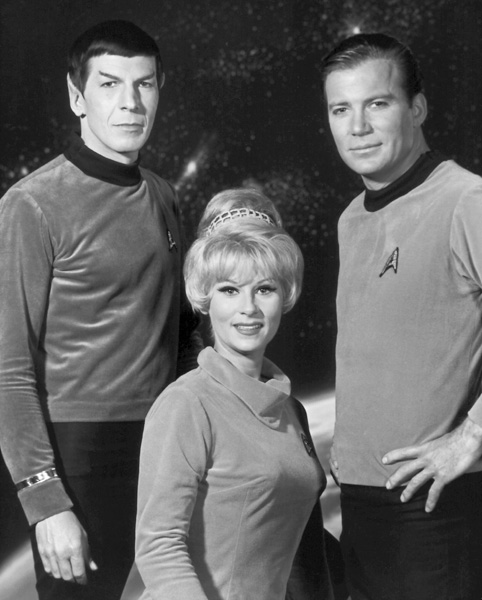

The show’s early publicity photos (including this one) seemed to suggest that the stars of Star Trek would be William Shatner, Leonard Nimoy, and Grace Lee Whitney. Nevertheless, Whitney was released midway through Season One, after appearing in just eight episodes.

March 9, 1967: “The Devil in the Dark” Airs

“The Devil in the Dark” remains notable in its own right for many reasons. It’s a terrific episode, with Kirk and Spock facing what seems to be a bloodthirsty monster, but which turns out to be a loving mother simply trying to protect her offspring. William Shatner considers this, along with “The City on the Edge of Forever,” the show’s high point, a sentiment shared by many fans. But the original broadcast of “The Devil in the Dark” had additional significance. As the end credits rolled, NBC made a voice-over announcement that Star Trek would return for a second season. This unprecedented, on-air renewal commitment ended a months-long letter-writing campaign in support of the program surreptitiously organized by Roddenberry and involving prominent science fiction authors, led by Harlan Ellison. On more than one level, it was a moment of triumph.

April 6, 1967: “The City on the Edge of Forever” Airs

And this installment marked another victory. Produced in February 1967, at great expense ($245,316, more than any episode other than the show’s two pilots) and after numerous painstaking rewrites (which sparked a decades-long feud between Roddenberry and screenwriter Ellison), “The City on the Edge of Forever” became the show’s most popular adventure and a television landmark. Among other accolades, this episode went on to win a Hugo Award for Best Dramatic Presentation.

June 4, 1967: The Emmy Awards

By the time the Emmys rolled around, Roddenberry and his team had already thrown themselves headlong into story development and preproduction for Season Two. But the show’s brain trust took time out to attend the ceremony because Star Trek was nominated in five categories including Outstanding Dramatic Series and Outstanding Performance by an Actor in a Supporting Role in a Drama (Leonard Nimoy). Unfortunately, Trek was shut out. Another rookie series from Desilu, producer Bruce Geller’s Mission: Impossible, was named Outstanding Dramatic Series. Nimoy lost to Eli Wallach for his work in the TV movie The Poppy Is Also a Flower. (At the time, supporting performers in TV movies and series competed in the same category.)

Nevertheless, Star Trek’s first season must be considered an astounding success. Despite unique production problems, oppressive budget restrictions, and incessant network needling, the show had proven critics wrong and built a loyal following. Out of imagination and elbow grease, long workdays and sleepless nights, Roddenberry, Coon, Fontana, Jefferies, Daniels, the cast, and the rest of the Star Trek team laid the foundation for a towering monument—the greatest franchise in science fiction history.