15

Little-Recognized Contributors

Star Trek turned its creator and principal cast members into household names. Even the show’s behind-the-scenes leaders—such as Bob Justman, Dorothy Fontana, Matt Jefferies, Bill Theiss and Fred Phillips—eventually earned due recognition for their superlative efforts. But, for a variety reasons, a handful of writers, craftspeople, and actors performed important functions on the program without receiving on-screen credit. As a result, many of these have yet to receive the accolades their contributions merited.

Isaac Asimov

Gene Roddenberry solicited stories and scripts from many esteemed science fiction authors. But Isaac Asimov, without penning a single teleplay, had greater influence on the development of Star Trek than any other sci-fi writer.

Asimov, a grand master of the genre who garnered six Hugos and three Nebula Awards in his lifetime, is best remembered for his panoramic, centuries-spanning Foundation series and for his many novels and stories about robots. He coined the term “robotics” in his 1941 short story “Liar!” Roddenberry first met Asimov in early September 1966 at WorldCon in Cleveland, under slightly embarrassing circumstances. Not realizing who Asimov was, Roddenberry shushed the author, who was chatting with a friend during the screening of Star Trek’s as-yet unaired pilot, “Where No Man Has Gone Before.” Afterward, Asimov graciously admitted he had been rude. Three months later Asimov wrote a short article for TV Guide bemoaning the poor quality and scientific inaccuracy of television sci-fi, including Star Trek. Roddenberry, chagrined, wrote a letter to Asimov defending his program as an earnest attempt to bring adult-oriented science fiction to TV.

This letter sparked a friendly correspondence between the two men. Asimov did an about-face and soon began promoting Star Trek whenever the opportunity arose. He was one of many authors who participated in the two “Save Star Trek” write-in campaigns. More importantly, Asimov began to suggest ways the show could be improved. Roddenberry deeply respected Asimov and implemented many of the writer’s ideas. Asimov’s input was not limited to scientific concerns but also included suggestions regarding character development and other storytelling issues. When Roddenberry expressed concern that Mr. Spock’s popularity had eclipsed that of Captain Kirk and irritation with the rift this had created between the show’s two stars, Asimov suggested that the two characters function more as a team. In a July 1967 letter to Roddenberry (reprinted in Herb Solow and Bob Justman’s book Inside Star Trek), Asimov wrote that Kirk and Spock should “meet various menaces together, with the one saving the life of the other on occasion. The idea of this would be to get people to think of Kirk when they think of Spock.”

Asimov remained a booster for the series even after its cancellation and was a guest of honor at the first Star Trek convention in 1972. Roddenberry hired Asimov to serve as scientific advisor for Star Trek: The Motion Picture (1979). This was the author’s only official Trek credit, but the franchise paid tribute to him several times over the years. On The Next Generation, Commander Data was given a “positronic” brain, a term lifted directly from Asimov’s robot stories. Asimov and his “Three Laws of Robotics” (programming that prevents androids from intentionally harming human beings) are mentioned by name in the TNG episode “Datalore.” The Deep Space Nine yarn “Far Beyond the Stars” takes place during the Golden Age of pulp science fiction and recasts the show’s regulars as the staff of a fictional SF magazine that supposedly publishes stories by Isaac Asimov and other famous writers. And the Voyager episode “Scorpion” features a character named Captain Amasov (commander of the Starship Endeavor), whose name was intended as a subtle tip of the cap to Asimov.

Majel Barrett

Majel Barrett’s contributions to the development of Star Trek went far beyond her performances as Nurse Chapel and the voice of the Enterprise computer. She was Roddenberry’s most trusted confidant and sounding board throughout the development and production of the show. Roddenberry made almost no major decisions about the program without asking for Barrett’s opinion. In author Yvonne Fern’s book Gene Roddenberry: The Last Conversation, a half-dozen prominent behind-the-scenes personnel, including associate producer Bob Justman, unanimously credit Barrett as the one person besides Roddenberry who did the most to shape the Star Trek universe. After her marriage to Roddenberry, fans fondly referred to her as “The First Lady of Star Trek.” She became the primary standard-bearer for the franchise following her husband’s death in 1991.

Wah Chang

The intimidating “alter ego” of the mysterious Balock, who plays a cat-and-mouse game with Captain Kirk and his crew in “The Corbomite Maneuver,” was one of sculptor Wah Chang’s many uncredited contributions. (1976 Topps trading card)

Sculptor Wah Chang produced a variety of iconic specialty props for Star Trek but never received credit for his contributions due to union rules. Since Chang’s Projects Unlimited wasn’t a union shop, he was prohibited from working on Star Trek. To bypass this restriction, Associate Producer Justman invented the fiction that the show was simply purchasing ready-made props from Chang, which was allowed under union regulations. However, Chang could not receive an on-screen credit for his contributions, which included the iconic communicator, phaser, and tricorder props; the monster suits for the Gorn from “Arena” and the Salt Vampire from “The Man Trap”; the Balok puppet from “The Corbomite Maneuver”; and the original Romulan Bird of Prey spacecraft from “Balance of Terror.” Due to budget constraints, Chang’s association with Star Trek ended midway through Season Two, but by then his creations had placed the sculptor’s indelible stamp on the program. For more about Chang and his work, see Chapter 12 (“Equipment Locker”).

Albert Whitlock

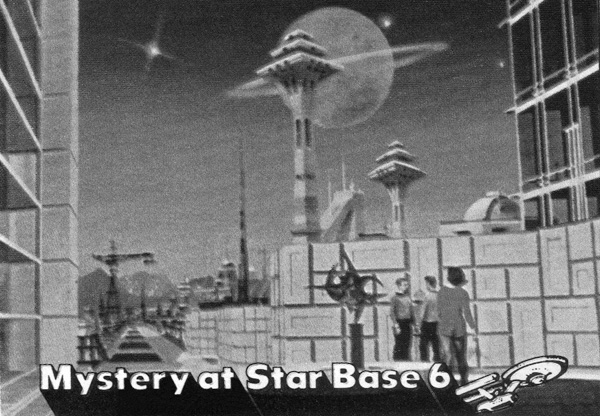

This view of Starbase 6 (from “The Menagerie”), one of artist Albert Whitlock’s most beautiful matte paintings, was immortalized on a 1976 Topps trading card.

Like Chang, matte painter Albert Whitlock established the look of Star Trek without receiving a single screen credit. Whitlock’s exotic alien landscapes added color to and enhanced the realism of several classic Trek adventures. For “The Cage,” he created the romantic, Indian-influenced vistas of Rigel IV; for “Where No Man Has Gone Before,” he painted the grungy, refinery-like towers and tubes of mining colony Delta Vega; and for “A Taste of Armageddon,” he depicted the gleaming cityscapes of Eminar VII. His work also appeared in “Court Martial” and “The Devil in the Dark.” Whitlock’s mattes were reused in several later episodes, including “Dagger of the Mind,” “The Conscience of the King,” “The Menagerie,” “The Gamesters of Triskelion,” “Wink of an Eye” and “Requiem for Methuselah.”

Matte paintings were utilized to create elaborate alien exteriors that could be realized no other cost-effective way using the technology of the era. While they functioned spectacularly as special effects, Whitlock’s mattes (painted in oils on masonite) also remain impressive as works of art, especially when viewed in person. His Rigel IV painting was displayed as part of Star Trek: The Exhibition, a collection of props, costumes, and other artifacts that began touring science museums across the U.S. in 2009. Unfortunately, in 2006, when Star Trek was remastered in high definition for release on HD-DVD and Blu-ray, some of Whitlock’s evocative paintings were digitally “touched up” or scrapped entirely in favor of new, computer-generated panoramas.

Whitlock was born in England in 1915 and began his association with motion pictures at Gaumont Studios at age fourteen, building sets and working as a grip. At Gaumont, Whitlock worked on several projects with Alfred Hitchcock, creating mattes and miniature effects for seminal thrillers such as The Man Who Knew Too Much (1934). He continued to work with Hitch through the years and created the eerie, crow-covered backdrop used in the final shot of The Birds (1963). Walt Disney brought Whitlock to America in 1950 and utilized the artist’s unique talents on feature films such as 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea (1954) and Darby O’Gill and the Little People (1959), as well as TV series like Zorro (1957) and Walt Disney’s Wonderful World of Color (1964). Whitlock also helped design Disneyland. He won Academy Awards in 1975 and ’76 for his contributions to the big-budget disaster films Earthquake and The Hindenburg, both of which featured amazingly realistic (and sometimes terrifying) matte effects. In all, Whitlock worked on more than 150 films and televisions shows, covering nearly every conceivable genre. He died in 1999 at age eighty-four.

Little-Recognized Recurring Cast Members

Think you can name all of Star Trek’s regular cast members? Maybe you can, but probably not. (If the names Bill Blackburn, Eddie Paskey, and Frank Da Vinci just rolled off your tongue, feel free to skip to the next subheading.) That’s because, in addition to the show’s instantly recognizable stars and supporting players, a half-dozen performers appeared regularly on Star Trek in relative anonymity. Most of them had few lines, and some never earned a screen credit, but they were present nonetheless—stationed in engineering, the transporter room, and even on the bridge, or standing in for the show’s leads during fight scenes.

Bill Blackburn appeared in sixty-one Star Trek adventures, usually as DeForest Kelley’s stunt double or as a gold-shirted extra (often a navigator or helmsman, sometimes referred to as Lieutenant Hadley). Blackburn, a former professional ice skater, also played numerous other bits and was the actor inside the rabbit suit in “Shore Leave.” Similarly Eddie Paskey, William Shatner’s stunt double, appeared in fifty-seven episodes, frequently as the red-shirted Lieutenant Leslie. Paskey also played the truck driver who runs down Edith Keeler in “The City on the Edge of Forever.” He later portrayed Admiral Leslie in the pilot episode of the fan-produced Internet series Star Trek: The New Voyages. Neither Blackburn nor Paskey ever received a screen credit and very seldom spoke a line, yet both played in more installments than George Takei (fifty-one episodes), Walter Koenig (thirty-six), or Majel Barrett (thirty-four). Frank da Vinci, who doubled for Leonard Nimoy, made a total of fifty-one uncredited appearances, thirty-two of those as the blue-shirted Lieutenant Brent. He played Vulcan background characters in both “Amok Time” and “Journey to Babel.” Recurring extra Roger Holloway made thirty-three uncredited appearances, often as security officer Lemli, and later turned up on an episode of Deep Space Nine.

Burly, blonde British actor John Winston played bit parts in eleven Star Trek adventures, usually as the red-shirted Lieutenant Kyle, often seen on the bridge or in the transporter room. Although Winston received screen credit and occasionally had dialogue, his character was never developed. In “The Immunity Syndrome,” William Shatner repeatedly mispronounces the character’s name as “Cowell.” Nevertheless, Kyle appeared in more episodes than Grace Lee Whitney’s Janice Rand. In “Mirror, Mirror,” Winston played both Kyle and Kyle’s evil Mirror Universe twin, who the Evil Spock punishes with an “agonizer.” The actor worked in episodes scattered throughout all three seasons and returned as Commander Kyle in Star Trek II: The Wrath of Khan (1982). (The Kyle character also appeared in six episodes of the Star Trek animated series but was voiced by James Doohan.) Winston also portrayed Captain Jefferies in the pilot episode of the fan-created Internet series Star Trek: The New Voyages, where he appeared alongside Eddie Paskey.

David Soul

Before gaining fame as Detective Ken Hutchinson on the cheesy cop show Starsky and Hutch (1975–79), David Soul played a young native of planet Gamma Trianguli VI in “The Apple.” Barely recognizable in a blond bouffant wig and red body paint, Soul (understandably) seems a bit awkward as Makora, who angers the godlike supercomputer Vaal by kissing his girlfriend Sayana (Shari Nims), copying the behavior of Enterprise crew members Pavel Chekov (Koenig) and Martha Landon (Celeste Yarnall). Although dozens of unknown actors played small roles on Star Trek, Soul (born David Richard Solberg in Chicago in 1943) was the only one to later achieve stardom. Soul began his performing career as a folksinger, opening concerts for the likes of the Byrds and the Lovin’ Spoonful. He parlayed his Starsky and Hutch fame into a successful recording career, cutting a soft-rock album that included the No. 1 single “Don’t Give Up on Us” in 1976. He followed with four more Top 20 singles and two Top 10 albums between 1976 and ’78. In the mid-1990s, Soul immigrated to England, where he became a regular on the West End stage. He acquired British citizenship in 2004.

Man of a Thousand Voices

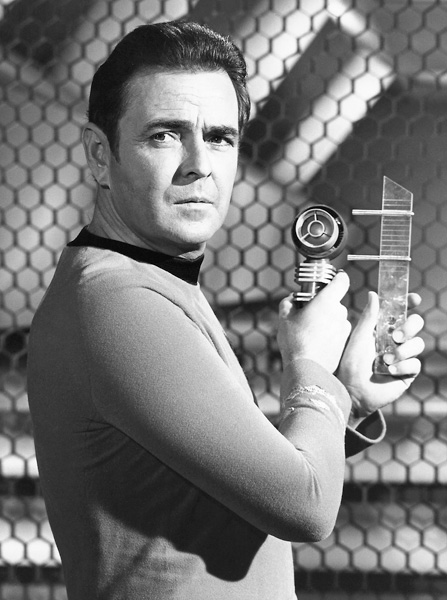

The versatile James Doohan not only played stalwart chief engineer Montgomery Scott but supplied the voices of several other characters on both the live-action Star Trek and the later animated series.

James Doohan became forever linked with indomitable Chief Engineer Montgomery Scott, but Scotty wasn’t the only role Doohan played on Star Trek. He was a masterful voice actor with a flair for accents that went far beyond Scotty’s familiar brogue, and directors often called upon Doohan to supply off-camera voice-overs. He was never credited for this voice work, and no official record of these contributions has been compiled, but the actor may have provided additional voices to a dozen classic Trek episodes or more. It’s known that Doohan voiced the following characters: Trelaine’s parents from “The Squire of Gothos”; Providers One and Two from “The Gamesters of Triskelion”; Sargon from “Return to Tomorrow”; the M-5 Computer from “The Ultimate Computer”; a radio announcer in “A Piece of the Action”; a NASA technician in “Assignment: Earth”; and the Oracle from “For the World Is Hollow and I Have Touched the Sky.” Doohan worked even more extensively on the Star Trek animated series, where he voiced more than fifty characters in addition to Scotty. In the lone animated adventure in which Scotty does not appear—“The Slaver Weapon”—Doohan supplied the voices of the three Kzinti aliens who menace Spock, Uhura, and Sulu.

Chef Roddenberry

In “Charlie X,” the telekinetically superpowered Charlie Evans (Robert Walker Jr.) overhears Captain Kirk asking the Enterprise’s chef to try to make meat loaf look like turkey for Thanksgiving dinner. A few minutes later, the astonished cook calls Kirk to report that “Sir, I put meat loaf in the ovens. There’s turkeys in there now—real turkeys!” The voice of the galley chief was supplied by the Great Chef of the Galaxy himself, Gene Roddenberry. It was the only acting role of his career.