16

Rivalries and Feuds

Star Trek was many things—a breakthrough in adult-oriented sci-fi television, an uplifting vision of the future, etc.—but it was never a candidate for one of those “Best Places to Work” lists. The grinding pressure to produce the ambitious series on the tight schedules and skimpy budgets of 1960s TV could be crushing. And this stress was only worsened by contentious relationships between members of the cast and creative leadership. The camaraderie displayed by the Enterprise crew on-screen belied the interpersonal tension that roiled the show off-screen.

William Shatner vs. Leonard Nimoy

When William Shatner signed on with Star Trek, it was with the understanding that his would be the face of the program. After all, he was the best-known and highest-paid member of the cast, and he played the captain. However, within weeks of the show’s debut, it became apparent that the character creating the most interest was not Shatner’s heroic Captain Kirk but rather Leonard Nimoy’s half-human First Officer Spock. Critics praised Nimoy’s work (the actor would earn three consecutive Emmy nominations), and Nimoy received much more fan mail than anyone else in the cast. This irritated Shatner. “I was now faced with no longer being the only star of this show,” Shatner wrote in his book Star Trek Memories. “And to be unflatteringly frank, it bugged me.” He felt jealous and insecure. “I wasn’t proud of these feelings, but they were simply the natural human reaction,” he wrote.

Shatner’s “natural human” feelings boiled over early one morning when a Life magazine photojournalist arrived in the dressing room to snap pictures of Nimoy’s transformation into Spock. Shatner, who, along with Nimoy, had an early makeup call (to affix his working toupee), resented the intrusion and ordered the photographer away. Nimoy was furious and pointed out that the visitor’s presence had been approved by both producer Gene Roddenberry and Desilu’s publicity office. “To which I apparently replied, ‘Well, it wasn’t approved by me!’” Shatner recalls in his autobiography, Up Till Now. “Why I responded this way I certainly don’t remember, but my envy certainly had something to do with it.” Nimoy stormed off to his dressing room and refused to report to work until Roddenberry came down and smoothed over the actor’s ruffled ego.

Shatner’s attitude accelerated Nimoy’s rapidly growing impression that he was underappreciated (not to mention underpaid) and that his character was getting short shrift. He lobbied continuously for scripts with larger and more interesting roles for Spock. Meanwhile, Shatner remained protective of Kirk’s primacy to the show’s teleplays. An on-again, off-again series of skirmishes ensued. In his memoir I Am Spock, Nimoy characterizes the tension between himself and Shatner as “sibling rivalry,” with Roddenberry (or associate producer Bob Justman or costar DeForest Kelley) stepping in to play Daddy and resolve disputes between “two squabbling kids.”

The situation festered into the show’s third season, when an exasperated Fred Freiberger (who replaced Roddenberry as the show’s line producer during its final year) finally corralled Shatner, Nimoy, and Roddenberry and demanded that the Great Bird of the Galaxy clarify once and for all who was the star of Star Trek. Roddenberry tried to evade the question, but when pressed he stated that Shatner was the star. This response inflicted further injury on Roddenberry’s already bruised relationship with Nimoy.

Years later, Nimoy stressed that even at their worst he and Shatner respected one another and enjoyed each other’s work, and their differences arose from similarly competitive temperaments. Once the show was off the air, and they began appearing together at Star Trek conventions without having to compete for lines in a script, Shatner and Nimoy finally buried the hatchet and became fast friends. They have remained close ever since.

Leonard Nimoy vs. Gene Roddenberry

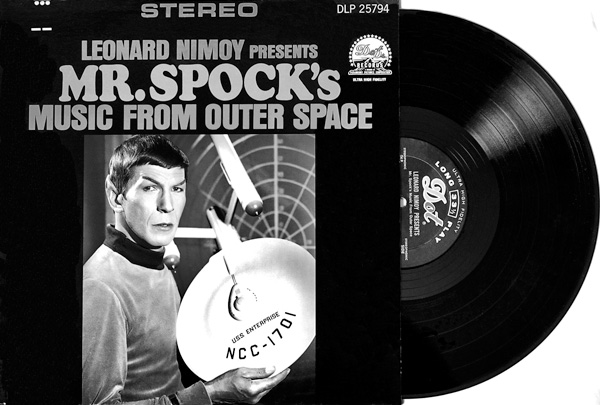

Dividing the profits from Mr. Spock’s Music from Outer Space, the first of four (!) albums Leonard Nimoy recorded for Dot Records between 1967 and 1969, exacerbated the strained relations between producer Gene Roddenberry and the actor-“singer.”

Tension developed between Nimoy and Roddenberry early on and steadily escalated throughout Star Trek’s first season. On a purely personal level the two failed to connect, in part because Nimoy considered Roddenberry’s frequent practical jokes (and not only those aimed at him) insensitive and in poor taste. More significantly, both Nimoy and Roddenberry were extremely protective of Spock. Each considered himself the character’s creator, yet the two sometimes disagreed about how the Vulcan should behave or speak in a given scene.

When Spock emerged as the series’ breakout character, Roddenberry and Desilu executives feared that Nimoy would demand more money—as indeed he did following Season One. Reluctant to establish precedents that might work against them in future negotiations, Desilu took a hard line in a series of petty disputes with the actor. For instance, Nimoy requested pens and pencils to reply to his copious fan mail. Even though Desilu provided Nimoy a $100 allowance toward the salary of a secretary, supplied Star Trek letterhead and publicity photos, and paid postage costs, the studio refused to give Nimoy any pens or pencils. Nimoy was also rebuffed when he attempted to install a telephone in his office (even at his own expense). At that point, the show’s entire cast and crew were sharing a single soundstage telephone. And Nimoy had to resort to theatrics—asking his secretary to feign heatstroke—to get a window air conditioner installed in his office, even with temperatures climbing toward 100 degrees. Although Roddenberry wasn’t directly involved in all these conflicts, Nimoy nevertheless blamed the Great Bird for refusing to intervene on his behalf.

The situation reached crisis proportions in the interim between Seasons One and Two. A gaping disparity in compensation existed between the show’s two leads during its first season: Shatner received a salary of $5,000 per week as well as 20 percent profit participation. He was also guaranteed a $500 per week raise every season the series was renewed. Nimoy was paid $1,250 per week with no profit participation. (Most of Star Trek’s other cast members were paid around $600 per show and were not guaranteed work in every episode.) As expected, Nimoy wanted to renegotiate before production began on Season Two. However, Roddenberry balked when Nimoy’s agent, Alex Brewis, demanded $9,000 per week, star billing, profit participation, and a percentage of the show’s merchandising, among other items. Alarmed, Roddenberry, Herb Solow, and Desilu’s other executive leadership, including attorney and contract negotiator Edwin Perlstein, considered recasting the role of Spock. Among those considered for the part were Mark Lenard, who had played a Romulan in “Balance of Terror” and would go on to portray Spock’s father, Sarek, in “Journey to Babel,” and Larry Montaigne, who had also appeared in “Balance of Terror” and would play Spock’s rival for his betrothed, T’Pring, in “Amok Time.” However, NBC was adamant that Nimoy be retained. Eventually, the two sides agreed on a new salary of $2,500 per week with better billing, more story input, and limited profit participation. The rest of the cast received smaller pay increases.

Even with the salary negotiation behind them, however, Nimoy and Roddenberry continued to clash. The next major dustup came when Dot Records signed Nimoy to a record deal. The company’s first Nimoy release was Mr. Spock’s Music from Outer Space (1967), featuring a cover photo of the actor-“singer” in full makeup, holding a model of the Enterprise. The album opens with Alexander Courage’s Star Trek title theme. Roddenberry demanded, and eventually received, a share of the royalties. To avoid future conflicts, Nimoy’s association with Star Trek was de-emphasized—and eventually eliminated—from the jacket artwork on his three subsequent Dot Records releases. Meanwhile, Nimoy continued to argue with Roddenberry over the development of the character of Spock. His disagreements with the Great Bird and other studio executives continued well after the cancellation of the show. The rebirth of Star Trek as a feature film franchise was delayed by an outstanding lawsuit the actor filed against Paramount Pictures for royalties from the sale of Star Trek merchandise. Nevertheless, in I Am Spock, Nimoy wrote that he is “deeply respectful of Gene’s creativity, his talent and his sharp intelligence,” and for Roddenberry’s tenacious fight with NBC prior to Season One to keep Spock aboard the Enterprise. “For that, I’ll always be grateful to him,” Nimoy wrote.

John D. F. Black vs. Gene Roddenberry

John D. F. Black served as Star Trek’s first story editor. He was also among the earliest victims of Roddenberry’s infamous practical jokes. One afternoon Roddenberry asked the newly arrived Black to interview an aspiring actress. The actress was actually Majel Barrett, who pretended to try to seduce the befuddled Black in order to win a part on the show. With Black squirming in his chair, Roddenberry and several cast members burst into the room, laughing hysterically. The embarrassed story editor shrugged off that incident but eventually grew frustrated by his lack of on-screen credit for the teleplays he polished. He also received no credit for coauthoring the show’s famous opening narration. “The Naked Time” remains his only official Trek writing credit. Under extreme pressure to meet airdates during the show’s inaugural season, Black was tasked with writing an “envelope” that would surround footage from “The Cage,” Star Trek’s rejected original pilot, and create a two-part epic. Roddenberry promised the network a two-parter that would wow viewers. More importantly, it would buy the show desperately needed breathing room in its production schedule. Black responded with the framing sequence for “The Menagerie,” with Spock commandeering the Enterprise to transport the disfigured Captain Pike to Talos IV. In an October 7, 1966, memo to associate producer Bob Justman (reprinted in Justman’s book Inside Star Trek), Roddenberry referred to “The Menagerie” as “fifty or sixty pages of pure genius.” Nevertheless, he rewrote the teleplay so extensively that, when it was done, he saw no need to credit Black. The finished script was credited entirely to Roddenberry, who had penned the original “Cage.” Black filed a grievance with the Writers Guild, demanding a credit, but lost. Embittered, Black quit the show in midseason and was temporarily replaced by Steve Carabastos. By the start of Season Two, Carabastos had been replaced in turn by Dorothy Fontana.

Harlan Ellison vs. Gene Roddenberry

Harlan Ellison was among the first of many acclaimed science fiction authors Roddenberry approached about writing for Star Trek. By 1966, Ellison had already won multiple Hugo and Nebula Awards for his groundbreaking short stories. He was also an experienced, talented screenwriter who had earned a Writers Guild Award for his classic Outer Limits episode “Demon with a Glass Hand.” The lone Star Trek episode Ellison penned—“The City on the Edge of Forever”—is widely regarded as the best of them all. This is the show where a delirious Dr. McCoy uses an alien time-travel device to return to Depression-era Earth and then alters history, with devastating consequences. Kirk and Spock follow McCoy into the past, where Kirk falls in love with beautiful young social activist Edith Keeler (Joan Collins)—only to discover that in order to correct the timeline, he must allow Keeler to die.

The reason Ellison wrote only one Trek teleplay is because he was irate with Roddenberry for making numerous changes to his original script. Ellison labored over “City” for months, writing and rewriting at Roddenberry’s request before turning in what he thought would be the final product. Nevertheless, major changes were made to the scenario by Roddenberry and his writing staff (including Steve Carabastos, Gene Coon, and Dorothy Fontana). In Ellison’s original version, Kirk and Spock travel back in time to undo damage caused by a murderous, drug-dealing crewman who escapes into the past. These elements were eliminated to avoid flack from network censors. The original script also includes a greater role for the Guardians, a race of time travelers who live in the titular “City on the Edge of Forever.” In a cost-cutting measure, this setting was also eliminated, reducing Ellison’s title to a poetic non sequitur. Perhaps most importantly, in Ellison’s version it’s the coldly logical Mr. Spock, not the love-struck Kirk, who prevents Keeler from being saved.

Despite the extensive rewrites, and even though he considered removing his name from it, Ellison received sole credit on the final version of the teleplay. But he was nevertheless incensed by the alterations. The author submitted his original “City on the Edge of Forever” script to the Writers Guild of America, where it won Most Outstanding Dramatic Episode Teleplay for 1967–68. After receiving the award, Ellison thumbed his nose at Roddenberry, who was in the audience. Roddenberry, not to be outdone, submitted the final version of “The City on the Edge of Forever” for consideration at the 1968 WorldCon science fiction convention, where it won a Hugo Award. Ironically, since Roddenberry didn’t attend the event, Ellison collected the trophy. The two bad-mouthed one another for decades, with Roddenberry often mischaracterizing elements of Ellison’s teleplay (for instance, making the erroneous claim that the original version had Scotty dealing drugs). Yet Ellison was invited to pitch an idea for the first Trek feature film in 1978 and, at the request of director Nimoy, consulted on the script for Star Trek IV: The Voyage Home (1986). Ellison got the final word by publishing his original “City on the Edge” teleplay in book form following Roddenberry’s death. This volume included a vindictive introductory essay in which he assailed Roddenberry’s “demented lies” and dismissed the broadcast version of the story as “crippled, eviscerated, [and] fucked-up.”

James Doohan, Walter Koenig, Nichelle Nichols, and George Takei vs. William Shatner

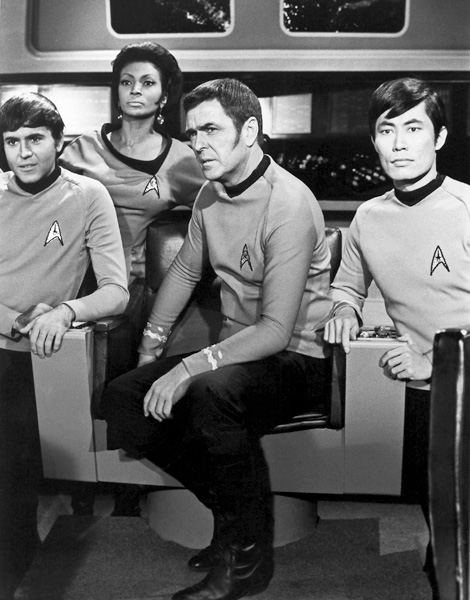

The “Gang of Four” (from left to right, Walter Koenig, Nichelle Nichols, James Doohan, and George Takei) all complained bitterly that William Shatner stole their lines and minimized their characters. But none of them confronted the star at the time.

Star Trek’s “Gang of Four” (so nicknamed by Walter Koenig) has vented its loathing toward star William Shatner countless times over the years. At conventions, in published interviews, and in their memoirs, Koenig, James Doohan, Nichelle Nichols, and even affable George Takei repeatedly have blasted Shatner for his treatment of Trek’s supporting cast. All four have complained about Shatner’s habit of stealing lines from their characters, often pulling directors aside and suggesting that dialogue originally scripted for one of the supporting cast be given to Captain Kirk. Episodes were written with little moments designed to flesh out the characters of Scotty, Chekov, Uhura, and Sulu and to provide screen time for the supporting cast. But Shatner, in his efforts to “protect” Kirk against the growing footprint of Spock in the show’s teleplays, believed it was essential that his character receive as many lines as the Vulcan, or more, and wasn’t particular about the source of the dialogue. If Shatner became involved in a screenplay early on, his suggested alterations might remove a supporting character from the story entirely—costing his fellow actor a week’s work (and a week’s pay).

Shatner “made it plain to anyone on the set that he was the Big Picture and the rest of us were no more important than the props,” Nichols wrote in her autobiography Beyond Uhura. “Anything that didn’t focus exclusively on him threatened his turf, and he never failed to make his displeasure known.” Resentment quickly grew among the supporting players. Doohan was especially disgruntled and often railed against Shatner at conventions. However, in his autobiography Beam Me Up, Scotty, Doohan wrote simply that “I just don’t like the man” and ventured: “It’s a shame that he wasn’t secure enough in himself or his status to refrain from practicing that sort of behavior.”

For his part, Shatner claims to have been unaware of the supporting cast’s feelings toward him until he set about interviewing them for his 1993 book Star Trek Memories. After concluding his interview with Nichols, the actress finally let Shatner know what she and the rest of the cast had never previously had the courage to reveal: That they despised their former Captain. Doohan refused to speak to Shatner at all. In 2010, Koenig blasted Shatner face-to-face in an episode of Shatner’s Raw Nerve, an interview show hosted by the erstwhile Kirk. But in his 1997 memoir Warped Factors, Koenig took a more conciliatory approach. “Bill Shatner has repeatedly said that he was not aware that we felt the way we did,” Koenig wrote. “Knowing his tunnel-visioned approach to his work I think that is possible. If that is true then we must share the burden of guilt with him.”

George Takei vs. Walter Koenig

Can a rivalry exist if only one of the two involved parties is aware of it? If so, then one briefly flared up between George Takei and Walter Koenig. Takei had signed on to appear in John Wayne’s Vietnam War film The Green Berets during the summer break between Star Trek’s first and second seasons. But when shooting of the movie ran long, Takei was forced to miss the first several weeks of filming for Season Two. As a result, episodes originally written to feature Sulu were hastily reworked for the show’s new addition, Ensign Pavel Chekov, played by Koenig. In his autobiography To the Stars, Takei writes that he was “heartsick and resentful” toward “the person to whom I had lost all my lines, an actor named Walter Koenig who had just sailed into our second season on the wings of fate, wearing that silly Prince Valiant wig.” Yet Takei—who by all accounts was one of the most agreeable and widely liked members of the cast—never voiced his jealousy. In fact, Takei remained so pleasant and endearing that Koenig wasn’t even aware of Takei’s feelings until the publication of To the Stars in 2007! Instead, Takei overcame his initial resentment and forged a warm and lasting friendship with his onetime rival. In 2008, Koenig served as best man at Takei’s wedding to longtime partner Brad Altman.