17

What Went Wrong with Season Three

By the end of its first season, Star Trek was firing on all nacelles, but most fans consider Season Two the show’s zenith. Nearly all the twenty-six episodes that first aired in 1967–68 were superb. Classic adventures that originated that season include “Mirror, Mirror,” the gripping parallel universe yarn featuring an evil, goateed Mr. Spock; “The Doomsday Machine,” a spacefaring variation on the theme of Moby Dick; “Amok Time” and “Journey Babel,” the first stories to explore Vulcan culture in depth; and “The Trouble with Tribbles” and “A Piece of the Action,” the show’s two funniest installments. In general, the series was imaginative and exciting, action oriented but rich in characterization, thought-provoking yet (usually) unpretentious. The working rapport between Kirk and Spock gelled, and the playful bickering between Spock and McCoy became a fixture. Ensign Chekov joined the bridge crew, and the supporting characters gained depth with increased screen time. For the second year in a row, Star Trek earned an Emmy nomination for Outstanding Dramatic Series.

Then it all seemed to fall apart with Season Three.

Star Trek’s devoted fans, many of whom had showered NBC with cards and letters to help save the series from cancellation the previous spring, eagerly anticipated the start of a new season’s worth of brilliant science fiction. On the night of September 20, 1968, Season Three finally began—with “Spock’s Brain,” widely reviled as the series’ single weakest episode. In this notorious clunker, Spock’s brain is stolen and plugged into a supercomputer that does all the thinking for a civilization comprised entirely of gorgeous but dim-witted women. Kirk leads an away team to the planet’s surface to recover the brain, bringing along Spock’s body, which somehow survived the brainectomy and now functions by remote control. When the end credits rolled on that fateful September night, fans must have stared slack-jawed at their TV sets, wondering if the writers of Lost in Space had taken over the show.

The truth behind Trek’s third-season decline was more complicated. It begins in July 1967, during the series’ Season Two heyday.

Lucy Sells Desilu

It was the Summer of Love. But even as tens of thousands of young people with flowers in their hair descended on San Francisco, corporate behemoths were gobbling up Hollywood. In 1967, the Seven Arts conglomerate bought the iconic but cash-strapped Warner Brothers Pictures, and Transamerica took over the enfeebled United Artists. The executives who authorized these deals knew nothing about moviemaking (Transamerica, for example, was a life insurance company whose other investment properties included Budget Rent-a-Car), but they recognized that the studios were underperforming assets that might regain value over time. Gulf + Western began the corporate takeover of Hollywood a year earlier by purchasing the tottering Paramount Pictures. Now the company wanted to expand into television and had its eye on neighboring Desilu Productions. The two studios’ parking lots were separated by a chain link fence.

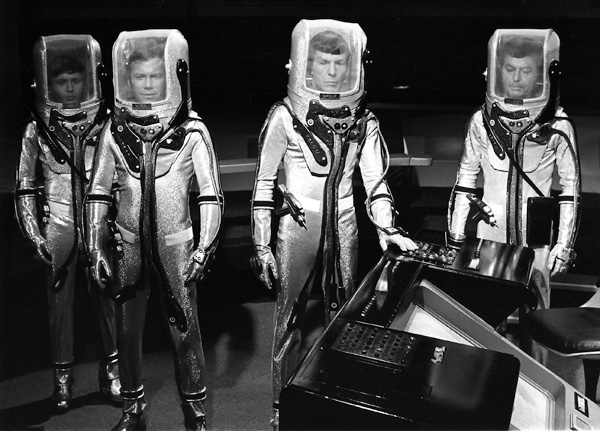

The remote-controlled Mr. Spock stands around uselessly while Kirk berates Kara (Marj Dusay) in this scene from “Spock’s Brain,” which opened Star Trek’s troubled third season.

Desilu had staged a comeback since the arrival of executives Oscar Katz and Herb Solow in 1964. It now had four series in production (The Lucy Show, Mission: Impossible, the detective show Mannix, and Star Trek) and others in development, but the studio remained unprofitable due to cost overruns. Ball—who became the first woman to head a Hollywood studio when she bought out her ex-husband Desi Arnaz in 1960—had grown weary of serving as Desilu’s president and chief executive officer while also starring in her own weekly series. On July 17, 1967, while director Marc Daniels was shooting “The Changeling,” Gulf + Western purchased Desilu for $17 million and officially renamed the company Paramount Pictures Television. Ball realized a profit on her initial investment but lost hundreds of millions of dollars in future revenues when the Star Trek franchise became enormously lucrative in the 1980s. Unfortunately, Gulf + Western—whose other divisions included sugar plantations in the Dominican Republic, textile mills, and auto parts factories, in addition to media properties such as Stax Records and Simon & Schuster Publishing—also failed to realize the potential value of Star Trek. Although there was little immediate impact from the sale on the show’s creative team, the parent company’s later meddling and penny-pinching would damage the series.

Gene Coon and Herb Solow Leave Star Trek

During his tenure on the show, Gene L. Coon was an anchor of the Star Trek production team. He signed on just prior to the shooting of “Miri” in late August 1966, replacing creator Gene Roddenberry as line producer, and left shortly after completion of “Bread and Circuses” in mid-September 1967. During that span, Coon oversaw the creation of thirty-one episodes, including many of the series’ finest efforts, and wrote classics such as “The Devil in the Dark,” “Space Seed,” and “Errand of Mercy.” Other than Roddenberry, no one more profoundly influenced the series’ emergent mythology. When Coon left the show in the fall of 1967, his personal life was in turmoil. The writer-producer left his wife, Joy, because he had fallen in love with model Jackie Mitchell, an old flame with whom he had recently reconnected. His divorce placed financial demands on Coon that forced him to take a higher paying job at Universal Studios, where he produced the Robert Wagner adventure series It Takes a Thief (1968–70). Under the pseudonym Lee Cronin, Coon continued to submit teleplays to Star Trek, but his editorial guidance was sorely missed. Coon’s replacement, John Meredith Lucas, wrote four Trek episodes and directed three others. But Lucas failed to impress Roddenberry in his new role and left the show at the conclusion of Season Two.

Herb Solow, who had been hired as an assistant by Desilu production chief Oscar Katz in 1964, assumed the title of Executive in Charge of Production following Katz’s departure the following year. Solow, a former NBC executive, was instrumental in Star Trek’s sale to NBC and spent much of the past three years running interference for Roddenberry with the network. After Paramount absorbed Desilu in the summer of ’67, Solow was invited to remain on board as the head of production for Paramount Pictures Television. He accepted but came to rue the decision when Gulf + Western financial executives began to insert themselves into the management of Paramount TV. In January 1968, the frustrated Solow jumped ship, joining Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer as a vice president. (MGM had been purchased by Canadian investor Edgar Bronfman Sr. in 1967 and would be sold again the following year.) While Solow’s departure didn’t directly affect the Star Trek’s creative team, his absence removed the firewall between Roddenberry and NBC and weakened the show’s defenses against tinkering Gulf + Western bean counters.

The Great Bird Flies the Coop

Like the show’s fans, Gene Roddenberry was relieved when NBC announced that Star Trek would return for a third season. But he was positively ecstatic when the network suggested the show might move to a more favorable time slot—Monday nights at 7:30—something Roddenberry had been lobbying for throughout the series’ first two seasons. Reenergized, he indicated he would resume duty as line producer, a responsibility he had handed off to Coon midway through Season One. But after further consideration, NBC decided to keep Star Trek on Friday nights, moving it back from 8:30 to 10 p.m. (According to some reports, Trek’s move to Mondays was scuttled by producers of the highly rated Rowan & Martin’s Laugh-In, who refused to surrender that show’s Monday 8 p.m. slot.) Roddenberry knew his show’s new “graveyard” time slot spelled doom for the series, since most of Trek’s young viewers would be away from their TVs on Friday nights. Dejected, he effectively absented himself from the program beginning in late March 1968.

Roddenberry always explained that he had threatened to remove himself from the show’s day-to-day operations unless NBC agreed to a better time slot; when NBC refused, he had to stand by his threat or else lose all leverage in further negotiations with the network. But if this was his thinking, then the Great Bird’s logic was less than Spock-like. If cancellation was now a foregone conclusion, what further negotiations was he concerned about? Solow, associate producer Bob Justman, and other insiders insist that Roddenberry was simply protecting his own interests, which is perfectly understandable. Roddenberry didn’t need a crystal ball to see unemployment looming in his near future. As a result, he devoted most of his energy during Season Three to developing ideas for other series and feature films he would pursue after Star Trek was gone, and to growing his fledgling Lincoln Enterprises souvenir business. Although he retained the title of Executive Producer and occasionally parachuted in to resolve conflicts among the cast and crew, he stopped submitting stories and rewriting teleplays and withdrew from most other production tasks. His name remained in the credits, but “the Roddenberry Touch” was gone.

The New Regime

When Roddenberry changed his mind about returning to line production for Season Three, Bob Justman believed he would assume the reins. After all, he had been with the program in various capacities since “The Cage” and had served diligently as associate producer during Seasons One and Two. But instead Roddenberry hired producer Fred Freiberger, who had worked on The Wild, Wild West and who was represented by Alden Schwimmer, Roddenberry’s agent. Justman received a new credit (the separate-but-unequal “co-producer”) and a pay increase, but Star Trek would not become his show. Bitter over this perceived betrayal and fed up with budget cuts and other headaches, Justman quit the show with eight episodes left in its final season.

Some argue that Freiberger has taken a disproportionate share of the blame for Trek’s drop-off in quality. Many of the producer’s other projects—including the TV series The Fugitive and The Six Million Dollar Man and the classic sci-fi movie The Beast from 20,000 Fathoms—demonstrate formidable talent. Nichelle Nichols, in her autobiography Beyond Uhura, insists that Freiberger “did everything he could to shore up the show. … Star Trek was in a disintegrating orbit before Fred came aboard.” To support Nichols’s argument, one can point to the departures of Roddenberry, Coon, and Solow, along with the show’s anemic budget, which NBC slashed to $178,500 for its third season, down $14,500 from Season One, despite salary increases for the cast and other rising production costs.

But if Freiberger was left holding the bag, he shook the remainder of its contents onto the floor. One of the things that had made the last season and a half of Star Trek so uniformly strong was the consistent presence of three very talented men—directors Marc Daniels and Joseph Pevney, and cinematographer Jerry Finnerman. Together, Daniels and Pevney had helmed twenty-eight of the show’s first fifty-five episodes, including most of its best-loved installments. On Freiberger’s watch, however, Daniels directed just one episode and Pevney none at all. Just six episodes into Season Three, Finnerman resigned, incensed when Freiberger demanded cuts in both the cinematographer’s pay and equipment allowance. Finnerman had photographed every Star Trek adventure since “Where No Man Has Gone Before,” creating a signature look for the program through his evocative use of colored gels and other lighting techniques. Al Francis, Finnerman’s camera operator, took over as cinematographer, but with Daniels, Pevney, and Finnerman out of the picture, Star Trek lost most of its previous visual style.

Poor Scripts and Script Supervision

Before Season Three began, Dorothy Fontana stepped down as story editor to focus on writing her own teleplays and to be free to write for other series. Freiberger replaced her with his friend Arthur Singer. Like Freiberger, Singer was experienced and talented—but knew nothing about Star Trek. As a result, the show suffered lapses in continuity and credibility. The lone episode Singer wrote himself, “Turnabout Intruder” (in which Captain Kirk switches bodies with a jealous ex-girlfriend) ranks among the least loved of the show’s original seventy-nine adventures. It was the final installment broadcast and ended the series with a sickening thud.

“Fred Freiberger came in and to him Star Trek was ‘tits in space,’” said screenwriter Margaret Armen, as quoted in Edward Gross’s book Trek: The Lost Years. “That’s a direct quote. I was in the projection room watching an early episode when Fred came in and watched it and said, ‘Oh, I get it. Tits in space.’ Fred was looking for all the action pieces, whereas Gene was looking for the subtlety that is Star Trek.”

To make matters worse, Roddenberry’s merciless rewriting of teleplays during the first two seasons had alienated some of the show’s better writers, making it tougher to acquire quality scripts. Few of the big-name authors who had contributed to Star Trek during Seasons One and Two wrote for the show during its final campaign. And some of the show’s stalwarts submitted subpar teleplays, such as Coon’s “Spock’s Brain” and Fontana’s “The Way to Eden,” in which the Enterprise is hijacked by a band of space hippies. (This was one of two Fontana scripts so heavily rewritten that the author removed her name from them.) Finally, in a cost-cutting measure, Gulf + Western insisted that Freiberger’s creative staff utilize stories that had been purchased during prior seasons but discarded as substandard. Coon’s “A Portrait in Black and White” (about warring aliens who are black on one side and white on the other) had been deemed too slow-moving and preachy. Yet it was revived and, under the new title “Let That Be Your Last Battlefield,” became another less than scintillating installment.

Assessing Season Three

Nearly everyone acknowledges that Star Trek’s third broadcast year marked a precipitous drop-off from the show’s first two seasons. The Hugo Awards provide one measure of the show’s declining quality. In 1967, “The Menagerie, Parts I and II” won the Hugo for Best Dramatic Presentation. That year two other Trek episodes were nominated in the same category (“The Naked Time” and “The Corbomite Maneuver”). In 1968, all five Hugo nominees in the category were Star Trek episodes—“The Trouble with Tribbles,” “Mirror, Mirror,” “The Doomsday Machine,” “Amok Time,” and the award-winning “City on the Edge of Forever.” But in 1969, Star Trek failed to earn a single Hugo nomination.

Still, Season Three could have been much worse. Given all the behind-the-scenes turmoil, it’s a wonder Trek didn’t become a complete disaster—“Spock’s Brain” week in and week out. Instead, the season proved to be wildly inconsistent. It included most of the series’ worst episodes but also some of its best, such as “The Enterprise Incident,” “Spectre of the Gun,” “The Empath,” and “The Tholian Web.” Season Three also remains notable for its many romances: An amnesia-stricken Kirk marries a native girl in “The Paradise Syndrome” (and continues his Playboy-of-the-Galaxy modus operandi in other episodes); Spock falls in love in “All Our Yesterdays” and seems smitten in “The Cloud Minders,” as well; Scotty and McCoy also find romance (not with each other) in “The Lights of Zetar” and “For the World Is Hollow and I Have Touched the Sky,” respectively. And Chekov makes time with young women in a handful of episodes. Meanwhile, Star Trek remained true to Roddenberry’s uplifting pro-humanist vision and established antiwar, prointegration advocacy. Episodes sometimes devolved into blatant sermonizing, as in “Let That Be Your Last Battlefield,” but Trek made history with TV’s first interracial kiss (between Kirk and Uhura, in the otherwise mundane “Plato’s Stepchildren”).

An away team consisting of (from left to right) Ensign Chekov, Captain Kirk, Mr. Spock, and Dr. McCoy beams aboard the disabled starship Defiant in “The Tholian Web,” a rare Season Three highlight.

With a new director at the helm almost every week, the show’s visual style became just as uneven as its teleplays. However, Freiberger encouraged directors to try new things, and some of those worked brilliantly, like Ralph Senensky’s use of fisheye lens point-of-view shots in “Is There in Truth No Beauty” and “The Tholian Web” to signify characters’ warped perspectives. On the other hand, without Finnerman’s sophisticated lighting, episodes occasionally looked downright garish. The show sometimes went over the top in other departments, too—with overblown makeup, costumes, and acting. Shatner, who in Star Trek Memories refers to himself as “the ham-asaurus,” raised scenery chewing to a new pinnacle in “The Paradise Syndrome.” (“I am Kirok! KIROK!!”)

Despite occasional lapses, however, what carried the day throughout Season Three was the excellent work of the show’s cast, and especially its leads. The acting styles of Shatner, Leonard Nimoy, and DeForest Kelley were as divergent as the personalities of the characters they portrayed, yet together they formed a perfect synthesis. From week to week, viewers tuned in because they remained deeply invested in Kirk, Spock, and McCoy, even if the trio’s adventures sometimes seemed a little silly. As a result, even the worst of Star Trek’s third season episodes ultimately seem endearing rather than insufferable.