21

Alternate Earths, Time Travel, and Parallel Dimensions

NBC continually pressured Star Trek’s creative brain trust for more “planet shows,” episodes where Captain Kirk and his crew fulfilled their mission to “explore strange new worlds” literally. But creating the sets, costumes, and makeup effects required for a planet show was expensive. With budgets tight and shrinking season by season, producer Gene Roddenberry and his team were compelled to shoot an increasing number of “ship shows,” with the action confined to the standing Enterprise sets. Many of the program’s finest adventures were ship shows (including “The Naked Time,” “Charlie X,” “The Doomsday Machine,” “Journey to Babel,” and “Space Seed,” among others), but the network’s thirst for planet shows remained unquenchable.

Roddenberry and his team developed a three-pronged strategy to sate NBC’s desire for planet shows while controlling costs, developing teleplays in which the Enterprise crew ventured to worlds that mirrored Earth, or traveled in time, or even crossed into other dimensions. Although born of necessity, some of these voyages helped expand the horizons of the franchise’s rapidly coalescing mythology.

Strangely Familiar Worlds

In their script for “Bread and Circuses,” Roddenberry and Gene Coon introduced “Hodgkin’s Law of Parallel Planetary Development,” a fictional principle that states that similar sentient species inhabiting planets with similar environments (for instance, humanoids from Earthlike Class M worlds) tend to develop similar cultures. This was the explanation given for the society of planet 892-IV, which mirrored the culture of ancient Rome, only with twentieth-century technology. While utterly ludicrous, Hodgkin’s Law serves as a prime example of the show’s ability to make even the most fanciful ideas sound reasonable by dressing them up in pseudoscientific jargon. Later, the biological applications of Hodgkin’s Law were used to explain why so many of the species Starfleet met as it expanded throughout the galaxy were bipedal mammals.

Roddenberry had planned for the Enterprise to visit parallel Earths from the beginning. The idea was included in his original prospectus for the series, where it was referred to as the “Similar Worlds Concept.” He noted in the proposal that this idea “gives extraordinary story latitude—ranging from worlds which parallel our own yesterday, our present, to our breathtaking distant future.” There were practical advantages, too. “Similar worlds” episodes could be shot on everyday locations or standing sets leftover from other productions and could utilize stock costumes and props. “Bread and Circuses,” for instance, reused wardrobe from movies including Cecil B. DeMille’s “The Sign of the Cross” and Joseph Mankiewicz’s “Cleopatra.” Also, placing Kirk, Spock, and friends in environments that approximated contemporary or historical settings invited the kind of Swiftian social commentary that, for Roddenberry, remained the program’s prime directive. “Bread and Circuses,” for instance, is a scathing satire of television, with Romanesque gladiatorial contests staged (and rigged) to maximize viewership. The Master of the Games (Jack Perkins) warns a producer, “You bring this network’s ratings down, Flavius, and we’ll do a special on you!”

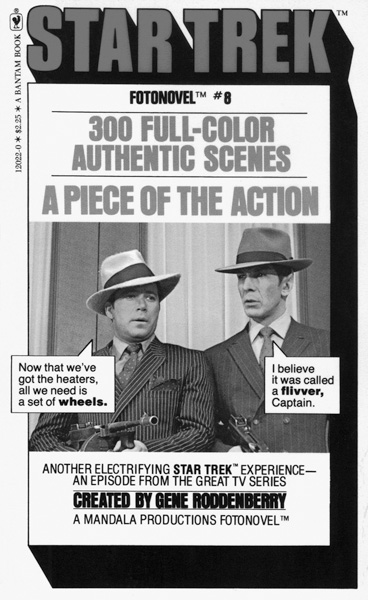

In “A Piece of the Action,” Kirk and Spock struggle to fit in on the gangster planet Sigma Iotia II, one of Star Trek’s many parallel Earths. (“Fotonovel” cover, 1977)

Unfortunately, the drawbacks to the parallel Earth concept were also significant, which is why the later Star Trek films and TV series generally eschewed such scenarios, even though Roddenberry had considered the concept foundational.

On a purely visceral level, mirror-Earth episodes could be a letdown for the audience. It was deflating to have the Enterprise trek halfway across the galaxy to reach a planet that looked like something viewers had seen many times before. And, perhaps because the Earthlike settings made the program’s allegories seem too obvious, the thematic content of these episodes often came across as clumsy or ham-fisted. That was certainly the case with such “similar worlds” tales as “The Omega Glory,” set on a savage world trapped in a centuries-old war between the Yangs (Yankees) and Kahms (commies), and “Miri,” featuring a planet devastated by medical experiments gone haywire. The results were better with “The Return of the Archons,” in which an Earthlike planet is subjugated by a totalitarian theocracy, and “Bread and Circuses” partially because both of those teleplays included a wicked streak of dark humor. Laughter atones for a multitude of sins.

Another major drawback to the “Similar Worlds” concept is that, Hodgkin’s Law aside, the idea of an alien planet developing into a virtual carbon copy of Earth is simply too preposterous to bear scrutiny. That problem was solved in a handful of episodes where a planet’s similarities to Earth were explained in different, more plausible ways. In “Patterns of Force,” for instance, the Nazi-like culture of planet Excalbia was the result of ill-advised meddling by a Federation cultural observer. In “A Piece of the Action,” the mobster society of planet Sigma Iota II arose when an Earth ship accidentally left behind a book about Chicago gangs of the 1920s. And in “Spectre of the Gun,” a landing party is sent to a ghostly recreation of 1880s Tombstone, Arizona, as a punishment for encroaching on the home world of the xenophobic Melkotians. Not coincidentally, these episodes proved far more effective than those that relied on the flimsy Hodgkin’s Law. “A Piece of the Action” and “Spectre of the Gun,” arguably, remain the most satisfying of all Star Trek’s alternate-Earth adventures.

Strange Old Worlds

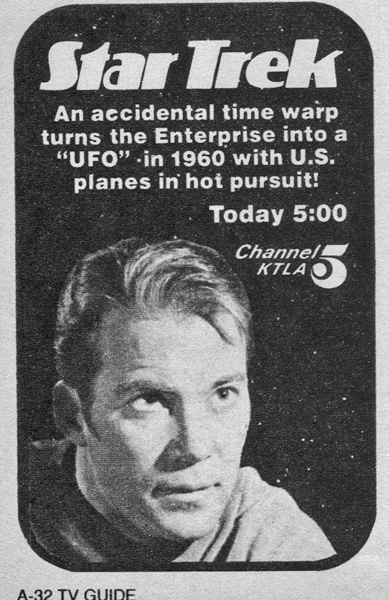

Another way for the program to employ contemporary, real-world locales was for the Enterprise—or members of its crew—to travel back in time, as happened on four memorable occasions. In “Tomorrow Is Yesterday,” the Enterprise is accidentally catapulted back to the 1960s and forced to rescue an Air Force pilot whose disappearance may alter history. In “The City on the Edge of Forever,” Kirk and Spock use an alien time portal to travel into the past and correct a damaged timeline caused by the actions of Dr. McCoy, who passed through the portal after an accidental drug overdose. In “Assignment: Earth,” the Enterprise travels back in time to conduct historical research and discovers an enigmatic alien time traveler who may be trying to alter history. And in “All Our Yesterdays,” Kirk, Spock, and McCoy use a different time portal to journey to different historical eras of planet Sarpeidon, which conveniently happens to be yet another parallel Earth. Kirk becomes entangled in the planet’s equivalent of the Salem Witch Trials, while Spock and McCoy are stuck in Sarpeidon’s ice age. The Enterprise also travels backwards in time, briefly, at the end of “The Naked Time,” which was originally planned as a two-part episode paired with “Tomorrow Is Yesterday.”

TV Guide advertisement for a syndicated rebroadcast of “Tomorrow Is Yesterday,” Star Trek’s first time-travel story.

Time travel, of course, has been a staple of science fiction at least as far back as H. G. Wells’s The Time Machine, first published in 1895. However, time-travel stories are notoriously troublesome. Even setting aside the overwhelming scientific implausibility of travel into the past or round-trip travel into the future, such stories present vexing narrative conundrums. Writers are forced to make tough choices about how time travel works in order to avoid the potential paradoxes such stories present. To cite the classic example: If you travel into the past and accidentally kill your own grandfather, would you cease to exist? And if you no longer exist, how were you able to travel back in time and nullify your existence? Perhaps by traveling back in time, you create an alternate timeline where you do not exist without affecting the original timeline in which you do exist. Or perhaps it’s safe to travel back in time because you cannot kill your own grandfather; it simply couldn’t happen that way because if it did, you wouldn’t have been around to make the trip in the first place. The possibilities are mind-numbing. Unfortunately, screenwriters never settled on a consistent, fully satisfactory set of rules governing the temporal mechanics of the Trek universe.

Even the great “City on the Edge of Forever” suffers from a gaping chasm of story logic. Moments after the Cordrazine-addled McCoy leaps through the Guardian of Forever, Captain Kirk attempts to contact his ship. The Guardian informs him that the Enterprise has vanished, along with the entire Federation of Planets, because the timeline has been altered. “All that you knew is gone,” the Guardian reports. The landing party is stranded, Spock says, “with no past and no future.” But this makes no sense. Why hasn’t the away team disappeared along with the ship? Surely the one cannot exist in this revised timeline without the other. It’s a classic case of the screenwriter (in this case, the esteemed Harlan Ellison) trying to have it both ways. The temporal logic involved in “Tomorrow Is Yesterday” and “Assignment: Earth” is no less convoluted.

Despite these flaws, however, Star Trek’s time-travel stories rank among the series’ most entertaining and enduringly popular installments. All four are lively, engrossing yarns with touching character moments and amusing comedic interludes, strengths that trump other shortcomings. Besides, audiences usually make greater allowances for time-travel stories. Maybe this is because time travel itself is so fantastic that the fine-grain details seem insignificant; in for a penny, in for a pound. Or perhaps viewers simply prefer to avoid the headache of working out the internal logic of such tales.

Whatever the reason, fans’ enthusiasm for episodes like “The City on the Edge of Forever” and “Tomorrow Is Yesterday” helped ensure that time travel would remain an important story element for the franchise. Every subsequent Star Trek series featured several time-travel tales, including classics like “Yesterday’s Enterprise,” “Cause and Effect,” and “All Good Things” from The Next Generation; “Past Tense (Parts I and II),” “Little Green Men,” and “Trials and Tribble-ations” from Deep Space Nine; and “Future’s End (Parts I and II)” and “Endgame” from Voyager. Star Trek: Enterprise’s “Temporal Cold War” was a recurring plot element that weaved its way in and out of numerous story arcs throughout the series’ four-season run. “Yesteryear,” the finest of Star Trek’s twenty-two animated episodes, was a time-travel story. And time travel figured in the plots of four of the eleven Trek feature films: The Voyage Home (1986), Generations (1994), First Contact (1996), and the Star Trek reboot (2009).

Strange New Dimensions

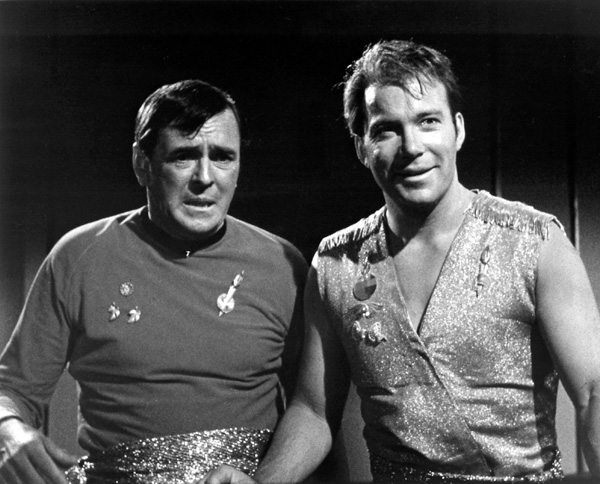

Scotty and Kirk, disguised as their Mirror Universe alter-egos, take a breather after mopping up sick bay with the Evil Sulu and his henchmen in “Mirror, Mirror.”

In addition to its travels through space and time, Star Trek sometimes ventured to even more exotic destinations: alternate dimensions. In “Mirror, Mirror,” a freak transporter accident sends Kirk, McCoy, Scotty, and Uhura to a twisted parallel dimension populated by evil duplicates of themselves and the rest of the crew. Although “Mirror, Mirror” was a ship show, the scenario was so colorful that it seemed like a planet show. Or at least it seemed to be taking place somewhere remarkably different than the familiar Enterprise. From a scientific perspective, of course, interdimensional journeys remain even more far-fetched than time travel (we know time exists, whereas the existence of alternate dimensions remains at best speculative). The possible existence of a mirror universes like the one depicted in this episode remains a hotly contested among theoretical physicists. Yet “Mirror, Mirror” remains a thrilling and thought-provoking yarn, and there’s no denying the sheer fun of meeting the villainous alter egos of the beloved Enterprise crew. Superbly produced and performed, “Mirror, Mirror” ranks among the most beloved of all Trek adventures. It belatedly spawned five Deep Space Nine episodes and a two-part Star Trek: Enterprise story arc.

Star Trek’s other interdimensional journeys didn’t make as big a splash but created some interesting ripples. In “The Tholian Web,” Captain Kirk is lost in an “interdimensional rift” while investigating the disabled USS Defiant. Star Trek: Enterprise’s two-part Mirror Universe adventure, “In a Mirror, Darkly,” concerned the fate of the Defiant, which slips through the rift both into the evil alternate dimension and back in time as well. In “The Alternative Factor,” an interdimensional fissure opens between our universe and a negatively charged parallel universe. The situation is further complicated by a mad alien (Robert Brown) bent on destroying his negatively charged doppelganger. Captain Kirk and crew must prevent Lazarus from coming into physical contact with the anti-Lazarus, since the ensuing repercussions could obliterate both universes. While not a scintillating installment, “The Alternative Factor” nevertheless spawned an animated tie-in. In the final episode of the Star Trek cartoon series, “The Counter-Clock Incident,” the Enterprise accidentally crosses over into this negative universe, where time runs backwards and the crew grows younger.

Strange New Worlds (Really)

Naturally, the Enterprise visited truly alien planets sometimes, too—just not as often as you might think. Excluding stories involving alternate Earths, time travel, and parallel dimensions, sixteen of twenty-nine Season One adventures can be categorized as planet shows (if you include “Court Martial,” which takes place on a space station). Thirteen of twenty-six Season Two installments were planet shows (counting “The Trouble with Tribbles,” also set on a space station), as were fifteen of twenty-four Season Three entries. However, this Season Three number is misleading and drops significantly if you exclude episodes such as “The Day of the Dove,” “The Lights of Zetar,” “The Way to Eden,” and “Turnabout Intruder,” which take place almost exclusively aboard the Enterprise, except for brief planet-side sequences. While those numbers would seem to validate NBC’s impression that Star Trek wasn’t exploring “strange new worlds” often enough, the network was also responsible for the show’s shrinking budget, which made producing such stories so difficult.

Besides, shooting a true, full-blown planet show was no guarantee of success. While some of the series’ finest installments fit this description (“The Menagerie, Parts I and II,” “The Squire of Gothos,” “The Devil in the Dark,” “Amok Time,” “The Empath,” etc.), so do many mundane, even subpar entries (“Operation—Annihilate,” “The Gamesters of Triskelion,” “The Paradise Syndrome,” “Spock’s Brain,” etc.).

What NBC, with its fetish for planet shows, seemed to miss was that there was no single blueprint for making a good Star Trek episode—and, in the final analysis, this was a good thing. If such an outline had been discovered, more consistently high-caliber episodes may have been produced, but the series inevitably would have taken on a monotonous, formulaic quality. Instead, the show’s producers and writers simply tried anything and everything they could think of. The result was a freshness, a vitality, a sense of adventure that more than compensates for the occasional clunker episode. Later Star Trek series and films strived to emulate the classic series’ willingness, even eagerness, to take risks. Through the original seventy-nine episodes, this freewheeling spirit was encoded on the DNA of the franchise and remains one of its greatest strengths.