23

Miracle Gadgets of the Twenty-Third Century

For many viewers, one of the most thrilling aspects of Star Trek is the wealth of futuristic technology featured on the show, devices with seemingly miraculous capabilities. From the beginning, viewers tuned into the series in part to ooh and ah (or at least exclaim, “That’s so cool!”) over gadgets like the transporter, communicator, and replicator. Detailed explanations of the inner workings of these and other twenty-third-century gizmos have been a staple of Star Trek literature as far back as Franz Joseph’s Star Trek Blueprints and Starfleet Technical Manual (both 1975) and Eileen Palestine’s Starfleet Medical Reference Manual (1977). As fresh and exciting as the show’s Treknological marvels seemed at the time, however, most had ample precedent in science fiction literature or films. And as far-out as many of them seemed then, at least a few of these devices actually exist today or seem to be on the cusp of reality.

Warp Drive

What it does: Enables starships to travel at speeds many times faster than light.

How it works: The engines warp space around the craft, contracting space in front of the ship and expanding space behind it. The vessel is propelled by the force of the warp itself, riding it “like a surfboard on a wave,” according to physicist Lawrence M. Krauss in his invaluable book The Physics of Star Trek.

Sci-fi precedents: Faster-than-light space travel is a long-standing fixture of literary and cinematic science fiction because it’s a priceless storytelling device. It’s virtually impossible to write spacefaring SF without it unless the story is restricted to our own solar system, which effectively rules out encounters with “new life and new civilizations.” Over the years, writers have suggested many different mechanisms for achieving speeds faster than light, some more plausible than others. In the Star Wars films, for instance, spacecraft cross over into “hyperspace,” temporarily entering an alternate dimension where our physical laws of relativity do not apply.

So when can I buy one? Not soon. As with many of the technologies seen on Star Trek, physicists grant that warp drive is theoretically possible. However, the energy required to warp space in this manner is almost beyond comprehension and certainly beyond current or foreseeable human capability. On Star Trek, engines generate this power through the controlled interaction of matter and antimatter, but this is a problematic solution for many reasons. In the real world, there is no proven way of harnessing the ensuing explosive reaction of matter and antimatter (dilithium crystals being fictional). Besides, antimatter is exceedingly rare, making it impractical for use as fuel.

However, in September 2011, physicists in Italy claimed to have clocked a subatomic particle called a neutrino moving at speeds faster than light—something believed impossible under Albert Einstein’s theory of special relativity. As of this writing (in the fall of 2011) the result remained unconfirmed, but if it is verified, this development could radically reshape our understanding of how space and time operate—and open a new frontier for research into faster-than-light travel.

The Transporter

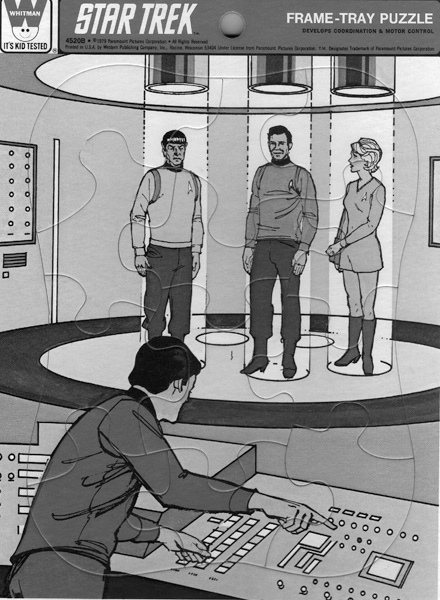

The transporter, depicted in this children’s jigsaw puzzle (vintage 1979), remains one of Star Trek’s most iconic technologies—and also one of its least plausible.

What it does: Moves people and cargo from one place to another almost instantly, dematerializing them at point A and rematerializing them at point B.

How it works: The transporter scans an object (or person) and stores a map of the subject’s molecular structure in a “pattern buffer.” Then it scrambles the object to basic molecules, transmits this raw matter to its destination, and then reassembles it according to the configuration stored in the buffer.

Sci-fi precedents: While not as pervasive a concept as faster-than-light travel, many stories and films have explored the idea of teleportation. Most of these have focused on the possible pitfalls of such technology, most famously The Fly (1958), in which a scientist tests an experimental transporter device and accidentally has his atoms mixed with those of a housefly. From a storytelling perspective, the transporter was a stroke of genius for Star Trek. It provided an elegant alternative to shooting expensive, repetitious scenes of the Enterprise landing and taking off in every episode. And it suggested intriguing plotlines for episodes such as “The Enemy Within,” in which a transporter malfunction splits Captain Kirk into two entities, and “Mirror Mirror,” in which another mishap transports an away team to an evil parallel universe.

So when can I buy one? Right after you ride your unicorn over to Frodo’s house and borrow his magic ring. The transporter defies so many of the basic laws of physics that it is, essentially, a fantasy element dressed up as science fiction. The theoretical ways of overcoming all the real-world obstacles to constructing such a device are convoluted and unlikely in the extreme. “No single piece of science fiction technology aboard the Enterprise is so utterly implausible,” Krauss wrote in The Physics of Star Trek. “Building a transporter would require us to heat up matter to a temperature a million times the temperature at the center of the sun, expend more energy in a single machine than all of humanity presently uses, build telescopes larger than the size of the Earth, improve present computers by a factor of 1,000 billion billion, and avoid the laws of quantum mechanics.” But after that, it’s a piece of cake.

Note: In late 2011, a Nova episode (part of the PBS Fabric of the Cosmos miniseries) described experiments taking place in the Canary Islands aimed at “teleporting” photons, comparing this process with the Star Trek transporter. However, the experimental procedure depicted involves the creation of an identical duplicate photon, rather than transporting the actual matter of the original photon. The process of creating the copy obliterates the original photon. This is quite a different proposition than the technology shown on Star Trek.

The Replicator

What it does: Converts inert matter into food … or anything else.

How it works: Based on the same technology as the transporter, the replicator dematerializes matter and then reconfigures it into any stored pattern, from a bowl of chicken soup to a phaser.

Sci-fi precedents: A handful of classic science fiction books and stories introduced similar devices, but the most memorable was author Damon Knight’s classic 1961 novel A for Anything (aka “The People Maker”). In this tale, a scientist invents a machine called a “Gismo” that can reproduce anything, including a human being or another Gismo. As a result, world economies instantly collapse, since Gismo users can, instantly and at virtually no cost, produce unlimited quantities of gold, diamonds, gasoline, or anything else imaginable. As Gismos spread, society breaks down and a repressive, slave-holding culture emerges.

For Star Trek, the replicator solves a thorny story problem (namely, how do you acquire and store enough food for a crew of more than 400 on a deep space voyage?). But Trek writers never seemed to grasp the full, revolutionary ramifications of this technology. A starship equipped with a replicator would never have to worry about running out of dilithium crystals—or anything else.

So when can I buy one? It will arrive in a convenient boxed set along with your transporter. Enjoy!

Phasers

Captain Kirk walked softly but carried a fully charged phaser. Will U.S. soldiers someday do the same?

What it does: Delivers a jolt of energy of variable intensity, mild enough to render an opponent unconscious or powerful enough to vaporize its target.

How it works: Phasers concentrate stored energy and then release it toward the target along a beam of light. They can be set for stun, heat, or kill. Starfleet officers carry small handheld phasers; starships are equipped with larger, more powerful versions.

Sci-fi precedents: Ray guns—laser pistols, blasters, death rays, and the like—have been around virtually as long as science fiction itself and are ubiquitous in the subgenres of military SF and space opera.

So when can I buy one? In the not-too-distant future. Maybe.

Since in the 1990s, the U.S. military has launched multiple projects aimed at the development of variable-power directed-energy weapons. While details on military research and development efforts are often classified, two such programs were active as of 2009, according to an article in Wired. One involves the development of the aptly named Phased Hyper-Acceleration for Shock, EMP and Radiation (PHASER). The idea is to create a rifle that fires a ball of lightning, which could be set to either stun or destroy and that could disable electronic equipment. Another active initiative is the Multimode Directed Energy Armament System (MDEAS). This concept involves using a laser pulse to create an ionized channel through which an electric shock can be fired at the target. Again, depending on the voltage, the charge sent could either stun or kill. Like the PHASER, the MDEAS would also be effective at wiping out enemy electronics. Both the PHASER and the MDEAS remain in development and could be years away from delivery, if they are delivered at all. In the early 2000s, after six years and more than $14 million, the military abandoned the Pulsed Energy Projectile (PEP) weapon, an earlier, similar project. Nevertheless, the military seems to be serious about developing a phaser-like weapon.

Tricorders

What it does: Combines scanning, analyzing and recording functions in a single handheld device. Several specialized models exist, including the medical tricorder, which is designed to detect changes in bodily functions and help diagnose illnesses.

How it works: Never fully explained.

Sci-fi precedents: Although they seem handy on Star Trek, similar devices rarely turn up in other SF books or movies.

When can I buy one? Sorry, you missed your chance! Beginning in 1996, Canada’s Vital Technologies Corporation began selling a unit it called the TR-107 Mark 1, marketed as a “real-life Tricorder,” which scanned for electromagnetic radiation and measured barometric pressure and temperature. Unfortunately, Vital Technologies went out of business in 1997. However, something more closely approximating an actual Star Trek tricorder could be on the horizon. In 2011, the X Prize Project, a philanthropic enterprise that grants lucrative cash awards to individuals and corporations who “bring about radical breakthroughs for the benefit of humanity,” announced a $10 million Tricorder Competition. The contest will reward the development of a handheld medical examination tool similar in function to those used by Dr. McCoy.

Communicators

What it does: Enables the user to communicate with the mother ship or other communicator-equipped personnel.

How it works: Flip it open and talk. Knob-twisting is optional.

Sci-fi precedents: The communicator was one of Star Trek’s snazziest-looking inventions and a widely influential one, but the idea of a handheld communication device was hardly original. Its many predecessors included the “signal watch” worn by detective Dick Tracy in Chester Gould’s classic comic strip as well as real-world walkie-talkies, which were used extensively on the battlefields of World War II.

So when can I buy one? You probably already own one. Cellular and satellite telephones are, essentially, communicators. Martin Cooper, the project manager whose team developed the first functional cell phone, freely admits that he was inspired by the flip-top communicators seen on Star Trek. In fact, if you have a smartphone, you have a more powerful device than a Star Trek communicator in most respects, capable of taking photos, recording sound, sending text messages, and uploading and downloading information from a computer network. From a post-iPhone perspective, it seems obvious that communicators and tricorders should have been combined into a single tool. Star Trek communicators represent an advance over modern cell phones only in terms of range and affordability. It is not yet possible to communicate with spacecraft via a cell phone, and Captain Kirk traveled throughout the galaxy without being slapped with a roaming charge.

The Universal Translator

What it does: Bridges the language gap, enabling the user to communicate with alien beings.

How it works: “There are certain universal ideas and concepts common to all intelligent life. This device instantaneously compares the frequency of brain wave patterns, selects those ideas and concepts it recognizes and then provides the necessary grammar.” That’s according to Captain Kirk, from “Metamorphosis.”

Sci-fi precedents: Like faster-than-light space travel, the concept of a universal translator is one of the most common in science fiction literature and movies, for obvious reasons. If you want to write a story about humans interacting with extraterrestrials, it’s very helpful if the two parties can converse with one another. And, as with faster-than-light spaceflight, numerous technologies have been suggested as the basis for a universal translator, some far-fetched. On Dr. Who, for instance, the TARDIS (Time and Relative Dimension in Space) mechanism projects a telepathic field that automatically translates most languages into English. In Douglas Adams’s satirical Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy books, universal translation is accomplished by inserting a symbiotic “Babel fish” into your ear! Many other works have proposed the development of a universal language. In the Star Wars universe they speak “Galactic Basic,” which sounds a lot like English.

So when can I buy one? If you have a smartphone, you can download it today. Or at least you can download the beginning of something like it.

In 2010, three different smartphone applications were released, all designed to instantly translate various spoken languages. Trippo Voice Magix, developed for the iPhone, translates English into fourteen languages. Another iPhone app, Speechtrans TM, instantly translates back and forth between American English, British English, French, German, Italian, Japanese, and Spanish. Speaking Universal Translator, an Android app, serves the same function for users of that smartphone brand, translating to and from English, French, Italian, and Spanish. Also, Google has announced plans to develop similar voice recognition/translation software for broader, non–cell phone use. It may be a while, however, before these programs enable us to communicate with extraterrestrials.

More Gadgets

The preceding is merely a representative sample of the many futuristic technologies employed by Starfleet. There are many more, some (including deflector shields, tractor beams, and artificial gravity) that are highly implausible and others (like the superadvanced, voice-activated Enterprise computer) that seem to be close at hand. (IBM’s “Watson” computer, which competed on the TV quiz show Jeopardy!, was inspired by the Enterprise computer.) Later Trek movies and series introduced other notable, and often far-fetched, technologies, such as the holodeck, first seen on the animated series, and Commander Data from The Next Generation.

One of the more fascinating aspects of Star Trek science is that it takes for granted the authenticity of telepathy and telekinesis, which are generally dismissed as superstition and pseudo-science and which might seem more the stuff of horror or fantasy than sci-fi. But the program’s acceptance of psychic phenomena (such as Spock’s mind melds) demonstrates the show’s prevailing attitude toward science and technology. The program readily embraced any and all scientific and pseudoscientific concepts, no matter how fantastic, if they were rich in story value. And, on a deeper level, Star Trek always erred on the side of confidence in human progress, whether this meant tapping into currently unproven psychic abilities or developing machines capable of overcoming apparently insurmountable scientific obstacles. In the world of Star Trek, human beings are limited not by the laws of physics but only by their own imaginations.