24

Memorable Musical Moments

If you’ve purchased (or borrowed or stolen) a copy of this book, chances are you’re a Star Trek fan. And if you’re a Star Trek fan, you can probably hum the show’s title theme from memory—and possibly a few other musical cues, as well. Perhaps you enjoy the singing of Nichelle Nichols or even (heaven help you) of Leonard Nimoy. But odds are that, one way or another, the music of Star Trek has burrowed itself into your brain.

That’s to be expected. Musical scores often play a vital role in the success of movies and TV shows, subtly enhancing the emotional impact of the drama unfolding on the screen. And many of Star Trek’s now-famous musical cues were repeated not only in episode after episode but within individual episodes. The occasional on-screen musical performances of the show’s cast remain unforgettable for other reasons, including a few that defy all efforts to blot them out.

“Theme from Star Trek ”

Star Trek’s immortal title theme—the brassy, bongo-driven, eight-note fanfare that plays under William Shatner’s narration (“Space, the final frontier …”)—was written by composer Alexander Courage for the show’s original pilot, “The Cage.” Variations on this theme were repeated in every episode and were consistently used to score exterior shots of the Enterprise. Series creator Gene Roddenberry hired Courage at the suggestion of composer Jerry Goldsmith, who had been the producer’s first choice to score “The Cage.” Courage wrote, arranged, and recorded the Trek theme in a single week, according to author Jeff Bond’s The Music of Star Trek. But the original orchestration was slightly different than the one used later, featuring electronic keyboard accents and shimmering vocal tonalities by operatic soprano Loulie Jean Norman. For the second Star Trek pilot, “Where No Man Has Gone Before,” Courage reorchestrated the theme, removing the keyboards and vocals and adding organ and flute, as well as (from his own mouth) the “whoosh” sound effects that coincide with the starship’s flybys.

Roddenberry restored Norman’s vocal track to the title theme for the show’s second and third seasons and remixed the music to feature the singer more prominently—so prominently, in fact, that Courage complained it now sounded like a soprano solo. By then, however, more contentious issues had arisen between Roddenberry and Courage. The contract the composer had signed contained a clause stipulating that if Roddenberry wrote lyrics for Courage’s theme, he would be entitled to 50 percent of Courage’s royalties from the composition. The producer’s awkward, sappy lyrics (“Beyond the rim of the starlight, my love is wand’ring in starflight …”) were never intended to be sung, let alone recorded, but they were duly filed with music licenser BMI. As a result, Courage’s Star Trek royalties dropped sharply. Roddenberry hadn’t informed Courage he planned to take advantage of the lyrics clause, which Courage had failed to notice when he signed his contract. The two exchanged testy letters, and Courage vowed never to work for Roddenberry again. Nevertheless, Courage eventually returned to the show during its final season, scoring the lackluster “Plato’s Stepchildren.” Goldsmith later hired Courage to orchestrate cues for his scores to Star Trek: The Motion Picture (1979), Star Trek: First Contact (1996), and Star Trek: Insurrection (1998). Courage worked extensively in film and television as a composer and orchestrator from the 1950s through the early 2000s and won an Emmy in 1988 for directing the music for a Julie Andrews Christmas special.

A swinging lounge version of Courage’s title theme is heard in the background of a party in “The Conscience of the King” and in a bar in “Court Martial.” “Theme from Star Trek” was also reprised in all eleven Trek feature films. Its opening notes were combined with Goldsmith’s “Star Trek March,” originally written for The Motion Picture, to create the title music for Star Trek: The Next Generation. The music was sometimes quoted by other Trek series, as well—perhaps most memorably at the conclusion of the final episode of Star Trek: Enterprise, as Scott Bakula read Shatner’s famous monologue. Numerous other movies and TV shows have also employed the theme, usually for comedic effect. Shatner and soprano Frederica von Stade recreated the Star Trek opening theme live for the 2005 Primetime Emmy Awards. Famed trumpeter Maynard Ferguson recorded a jazz-rock fusion version of the theme for the 1977 album Conquistador. For her 1991 album Out of This World, Nichelle Nichols recorded a disco version of the theme featuring original lyrics (not Roddenberry’s). Actor Jack Black’s mock-and-roll band, Tenacious D, recorded the theme using Roddenberry’s lyrics, releasing the track as a B-side.

“Mr. Spock Theme”

For the classic episode “Amok Time,” in which Spock goes into a Vulcan form of heat known as Pon Farr, composer Gerald Fried created a brooding theme, plunked out by guitarist Barney Kessel on an electric bass, which instantly became one of the show’s most distinctive compositions. Spock “struggled to express emotion, so I picked an instrument where emotion is a struggle to express, like the bass guitar,” Fried told Bond in The Music of Star Trek. “I felt somehow [this approach] might match Spock’s inability to be emotionally accessible.” The instantly recognizable “Mr. Spock Theme” was reused in “Journey to Babel” and “The Changeling,” among other episodes. Fried was one of a handful of composers who stepped in to fill the void created by Courage’s departure from the show. He later shared an Emmy Award with Quincy Jones for his contributions to the score of the landmark miniseries Roots (1977). Jazz guitarist Kessel was a veteran session player who had performed with luminaries such as Oscar Peterson, Charlie Barnet, Artie Shaw, and even Chico Marx (yes, that Chico Marx) during a career that began in the 1940s and lasted until 1992, when he suffered a debilitating stroke. For “Amok Time,” Fried also composed the stirring “Ritual/Ancient Battle” suite, which henceforth served as the series’ default music for nearly every fight scene, including the battle sequences from “A Private Little War” and “Bread and Circuses.”

“Good Night, Sweetheart”

Fred Steiner wrote more music for Star Trek than any other composer. Associate producer Bob Justman brought him back time and again because he adored Steiner’s work. “My first choice, always, unless there was a particular reason, was Fred, who caught the inner being of Star Trek,” Justman told Bond in The Music of Star Trek. Roddenberry instructed all the show’s composers to avoid ethereal, self-consciously “spacey” compositions. But “even before I had that conference with Gene Roddenberry, I think I’d made the decision that it had to be old-fashioned, blood-and-guts music,” Steiner said. His most memorable Star Trek music was originally written for early episodes such as “The Corbomite Maneuver,” “Charlie X,” and “Balance of Terror,” and repeated endlessly in many later installments. For example, his menacing “Romulan Theme” from “Balance of Terror” served as a leitmotif for villains of all sorts in many adventures and was used extensively in the Evil Mirror Universe scenes from “Mirror, Mirror.”

But Steiner could do more than “blood and guts” music, as evidenced by his lilting romantic themes from “What Are Little Girls Made Of?” and “Elaan of Troyius.” For “The City on the Edge of Forever,” Steiner searched for a period love song to play under Captain Kirk’s scenes with the doomed Edith Keeler (Joan Collins). He decided to use English bandleader Ray Noble’s chart-topping hit “Goodnight, Sweetheart,” which in “City on the Edge” is first heard playing on a radio and later reappears as a love theme during all of Shatner’s subsequent scenes with Collins. Even though the song was a minor anachronism (Noble’s record was released in 1931; the story takes place in 1930), the tune worked beautifully, providing a quaint, plaintive musical backdrop for the budding but hopeless romance. Unfortunately, Paramount later lost the rights to the song. When Star Trek was first released on videotape in the 1980s, “Goodnight Sweetheart” had to be replaced and the episode’s romantic interludes rescored without Steiner’s input. Thankfully, Paramount eventually recovered the rights to “Goodnight, Sweetheart” and restored the original music for Star Trek’s DVD release.

Steiner also wrote scores for The Twilight Zone and Lost in Space, as well as the famous title theme from the classic legal drama Perry Mason. In 1985, he earned an Oscar nomination for his music from the film The Color Purple.

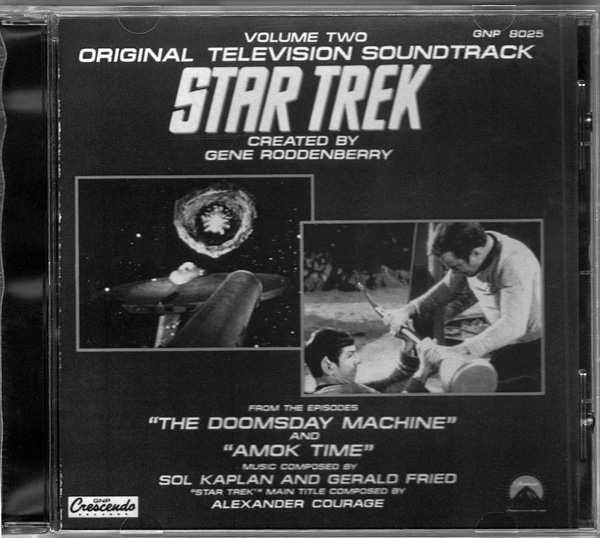

“The Doomsday Machine”

Two of Star Trek’s most memorable scores, Gerald Fried’s inventive “Amok Time” and Sol Kaplan’s powerful “The Doomsday Machine,” were released together on this Crescendo label CD.

Original music was created for just thirty-five of Star Trek’s original seventy-nine episodes—and many of those were partial scores, with new themes supplemented by library cues. In most cases, music editor Richard Lapham cobbled together all or part of an episode’s score out of recycled and leftover cues from previous installments. This practice—known in the industry as “tracking”—is no longer permitted by the American Federation of Musicians. Full, new scores were created for every episode of every subsequent Star Trek live-action series. But AFM rules during the 1960s were more lenient. The union required just thirty-nine hours of recording time per twenty-six-episode season—hardly an extravagant amount considering that it took between four and five hours to record the twenty-one minutes of music written for “Charlie X” alone.

Composer Sol Kaplan provided a rare, fully original score for “The Doomsday Machine.” His thrilling score, which makes evocative use of piano, woodwinds, flute, and cellos, is now revered as the program’s musical high point, rivaled only by Fried’s inventive “Amok Time.” Kaplan’s urgent, spine-tingling “Planet Killer” theme prefigured John William’s remarkably similar score for Jaws (1975).

Uhura Sings

The emblematic scores of Courage, Fried, Steiner, Kaplan, George Duning, Jerry Fielding, and Joe Mullendore served as Star Trek’s musical hallmarks. But the show’s stars and guest stars sometimes provided musical interludes, as well. Most of these are burned indelibly in fans’ memories—for one reason or another. Fans’ more pleasant recollections often stem from the handful of vocal performances by Nichelle Nichols, who spent years touring as a jazz vocalist before joining Trek.

With “Charlie X,” the seventh episode produced, Nichols made her Star Trek singing debut. Originally, screenwriter Dorothy Fontana had written a scene where Lieutenant Uhura entertains her shipmates in the Enterprise recreation room by doing an impression of first officer Spock. However, the sequence was retooled to take advantage of Nichols’s vocal talents. Instead of mimicking Spock, she sings a song (“Oh, on the Starship Enterprise”) that pokes good-natured fun at her superior officer, who accompanies her on his Vulcan lute: “Oh, on the Starship Enterprise there’s someone who’s in Satan’s guise/Whose devil’s ears and devil’s eyes could rip your heart from you …” Later, to the same melody, she sings “Oh, Charlie’s Our New Darling,” about new arrival Charlie Evans (Robert Walker), a teenager with powerful but as yet unrecognized psychic abilities: “Now from a planet out in space there comes a lad not commonplace/A-seeking out his first embrace …” Charlie, who doesn’t appreciate the joke, renders Uhura temporarily mute. The tune Nichols sings is derived from the Scottish folk song “Charlie Is My Darling.” (The “Charlie” of the song’s title was the exiled prince Charles Edward Stuart, a Catholic who in 1745 unsuccessfully attempted to retake the British throne from the protestant George II.) It’s unclear who wrote the new lyrics for “Oh, on the Starship Enterprise” or “Oh, Charlie’s Our New Darling.”

Nichols’s favorite of Uhura’s songs was “Beyond Antares,” a love song with music by Desilu music consultant Wilbur Hatch and lyrics by producer Gene L. Coon. She sang the number twice, first in “The Conscience of the King” and later in “The Changeling” (in which her performance caused the puzzled NOMAD to drain Uhura’s brain). Although its lyrics are asinine (“the skies are green and glowing” … “the scented lunar flower is blooming”), the song’s melody is enchanting, and Nichols delivers a committed, sensitive a cappella vocal in both episodes. She recorded a fully orchestrated version of “Beyond Antares” for her 1991 album Out of This World. She also recorded a version of the song for her self-produced 1986 cassette release, Uhura Sings.

Spock ’n’ Roll Music

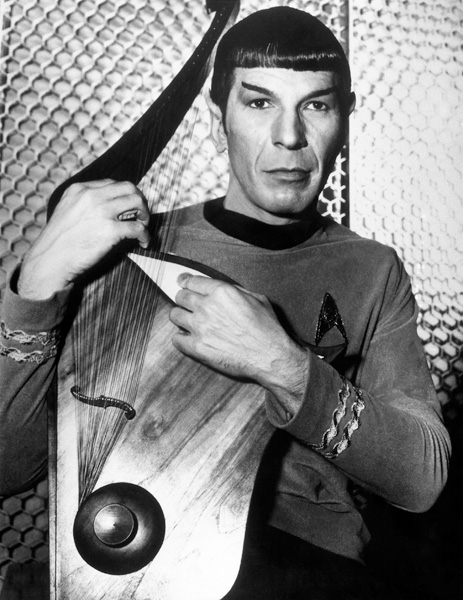

Unfortunately, Star Trek’s other most frequent musical stylist was Leonard Nimoy, whose contributions proved less pleasing than Nichols.’ In several installments, Spock can be seen playing his Vulcan lute—an instrument designed by sculptor Wah Chang purely for its appearance rather than its sonic qualities. According to author Franz Joseph’s Starfleet Technical Manual (1975), the instrument “combines the tonal qualities of a harp, lute, sitar, and to some extent, violin.” Nevertheless, Spock’s musical performances were less than scintillating—especially when Nimoy was required to sing. In the episode “Plato’s Stepchildren,” Spock croaks out “Maiden Wine,” an original composition by Nimoy that later appeared on his album The Touch of Leonard Nimoy.

Without question, however, Spock’s ill-advised jam session with the space hippies from “The Way to Eden” marked Star Trek’s musical nadir. Although Spock plays a fairly inoffensive instrumental—dueting with Mavig (Deborah Downey) and her unnamed, wheel-shaped, harplike instrument—it’s appalling to see the dignified Vulcan sink to the level of these addle-brained doofuses. Throughout this abysmal episode, hippie second banana Adam (Charles Napier) belts out a series of dippy folk-rock tunes, reportedly composed by Napier himself. This musical assault begins, appropriately enough, in sick bay, where Napier warbles a tune that might be called “In the New Land” (these poorly structured numbers contain no choruses, making titles guesswork). It continues with a four-minute medley in the rec room (“Long Time Back When the Galaxy Was New”/“There’s a Wide Wide Emptiness Between Us (Brother)”/“Hey Out There”) that eventually gives way to The Spock-and-Mavig Experience. Finally, after the hippies have assumed control of the ship, Napier croons the ballad “Headin’ Out to Eden” in the auxiliary control room. Eventually, Adam meets a gruesome fate—he dies from eating poisonous fruit—but perhaps not gruesome enough for agitated viewers who, reeling from this sonic onslaught, may have been tempted to smash their Simon and Garfunkel albums as a precautionary measure. “The Way to Eden” featured Spock’s final screen appearance with his lute. Pity he went out on such a sour note.

Other Musical Interludes

A handful of other musical moments should be noted:

• The Irish jig Gerald Fried wrote as a leitmotif for Captain Kirk’s Starfleet Academy nemesis Finnegan in the episode “Shore Leave” might seem like such an idiosyncratic piece of music that it would seldom be reused. And yet the ditty was revived, for comic effect, several times, in episodes such as “This Side of Paradise,” “The Apple,” and even “The City on the Edge of Forever,” where it’s heard when Kirk and Spock encounter a surly Irish cop.

• The composition that Spock discovers and plays in “Requiem for Methuselah”—attributed to Brahms in the episode—is not actually a classical piece. It was a Brahmsian pastiche written especially for the episode by Ivan Ditmars, at the request of Wilbur Hatch. This was the only Star Trek assignment for Ditmars, who from 1963 through 1972 served as the organist/musical director for the daytime game show Let’s Make a Deal.

• On the other hand, the harpsichord music Trelaine is playing when he first meets Captain Kirk and his landing party during “The Squire of Gothos” is a classical composition—namely, Johann Strauss’s “Roses from the South.”

• And, finally, what Trek devotee could forget the singing of actor Bruce Hyde, who delivered the longest vocal performance in Star Trek history—spanning more than twelve minutes of screen time, on and off—as mentally incapacitated navigator Kevin Riley in “The Naked Time.” Fancying himself as a captain, Riley commandeers the intercom and sings interminable choruses of “(I’ll Take You Home Again) Kathleen,” which he occasionally interrupts to deliver absurd orders such as “in the future, all female crew members will wear their hair loosely about their shoulders.” Riley’s cringe-inducing crooning inspires another crewman to serenade Yeoman Rand with a variation of the same ditty and drives Captain Kirk to distraction. “One … more … time!”

Spock and his Vulcan lute. (Sans space hippies, thank heavens.)