27

Leonard Nimoy Discovers Spock

Unlike William Shatner, who was classically trained, and DeForest Kelley, who rose through the ranks of the Hollywood studio system, Nimoy was a devotee of the Method—an intimate, psychological approach to the craft originated by Constantin Stanislavski in the late nineteenth century and advanced in America by Lee Strasberg’s Actors Studio beginning in the 1940s. Prior to signing on with Star Trek, Nimoy taught the Method to pupils in Hollywood (for years these classes had been his steadiest source of income). Method actors do not shape their characters so much as they allow themselves to be shaped by their characters. That was certainly the case with Nimoy and Spock. Nimoy thinks of Spock not so much as a creation but as a discovery. A sampling of key episodes reveals the growing rapport between actor and character (or vice-versa).

“Fascinating”

In Star Trek’s original pilot, “The Cage,” Nimoy played a very different Spock—the character’s coolly logical personality was not yet defined. In the second pilot, “Where No Man Has Gone Before,” Nimoy portrayed a more recognizable Spock, but not particularly well. The actor seems stiff and uncomfortable. In his two memoirs, Nimoy credits director Joseph Sargent with fostering a creative breakthrough. During the filming of “The Corbomite Maneuver,” the first regular Star Trek episode produced, Nimoy felt unsure how to handle an early scene in which the Enterprise encounters a giant spacecraft. The rest of the bridge crew seems intimidated by the huge alien vessel, but Sargent instructed Nimoy to read his one-word line—“Fascinating!”—with a kind of detached scientific curiosity, completely free of anxiety. “What came out wasn’t Leonard Nimoy’s voice, but Spock’s,” Nimoy wrote in I Am Spock. “I began to seriously understand where Spock was coming from.” The dialogue between character and actor had begun. And the word “fascinating” instantly became a signature expression for the character.

Improvising the FSNP

Just two episodes later, during the production of “The Enemy Within,” Nimoy’s link with the character was strong enough that he was able to improvise what would become another Spock trademark—the Vulcan nerve pinch. Richard Matheson’s teleplay called for Spock to clobber the Evil Kirk with a haymaker, but Nimoy felt the refined, violence-averse Vulcan should have a subtler way of incapacitating his opponent. So he ad-libbed an alternative (Spock pinches Kirk at the base of the neck; Kirk instantly collapses) and rehearsed it with Shatner between camera setups. Nimoy and Shatner demonstrated the gag for director Leon Penn, who loved it and incorporated it into the scene. The maneuver became so well known and frequently repeated that later Trek teleplays often referred to it as simply the “FSNP,” short for Famous Spock Nerve Pinch. This was only the first in a series of inspired improvisations that Nimoy devised (or, the actor might suggest, that Spock gave him), which became trademarks for the character and linchpins of the show’s rapidly coalescing Vulcan mythology.

Spock Weeps

The most impressive—and moving—of all Nimoy’s improvisations was a brief sequence the actor invented for “The Naked Time,” in which Spock, infected by a virus that breaks down emotional inhibitions, locks himself away in a briefing room and cries. John D. F. Black’s teleplay called for Spock to burst into tears in the hallway of the Enterprise; then a laughing crewman was supposed to paint a mustache on the crying Vulcan. Nimoy considered the scene beneath the dignity of his character. However, he believed the scenario provided an opportunity to dramatize Spock’s perpetual inner conflict—with his detached, logical Vulcan side battling his emotional human side and, at least this once, losing. Spock would never cry in public, Nimoy reasoned, but would hide himself away and try to quell his surging emotions. Director Marc Daniels agreed and worked out the blocking and camera movement for the scene with Nimoy. As the briefing room door slides shut behind him, Spock attempts to steady himself. “I am in control of my emotions,” Nimoy says, clenching his teeth. (All the dialogue for this sequence was ad-libbed.) Then he begins to sob, staggering across the room and collapsing into a chair. Staring at a blank computer screen, still talking to himself, he struggles not to weep. Daniels’s camera slowly dollies in and then glides 180 degrees around the actor, ending in close-up on Nimoy’s tear-streaked face. It’s a brilliantly imagined and deeply touching little scene, one that helped endear the Vulcan to thousands fans—and one that Nimoy, amazingly, nailed in a single take.

Spock in Command

“The Galileo Seven” was one of the first teleplays designed to meet the network’s demand for more Spock-centric adventures. Nimoy is the de facto star of this installment, in which a shuttlecraft crashes on planet Taurus II. There Spock, McCoy, Scotty, and four other crew members struggle to effect repairs while fending off attacks from a race of giant anthropoids. McCoy refers to the catastrophe as Spock’s “big chance”—his first command. Spock pooh-poohs the idea—“I neither enjoy the idea of command, nor am I frightened of it,” he says. “It simply exists.”—but a hint of eagerness in Nimoy’s voice suggests that the confident-sounding Vulcan secretly relishes the prospect of proving that logic is the best basis for leadership decisions. As usual, the actor’s approach remains delicate and low-key; the more alarmed and overwrought his crew becomes, the more still and quiet Nimoy grows, underscoring Spock’s separation from the humans.

The crew is put off by Spock’s matter-of-fact assertion that some of them may need to be left behind to allow the others to escape—and that as commander Spock will decide who stays and who goes. The Vulcan is never comforting or conciliatory. Eventually, however, Spock realizes that command—command of humans, at least—requires more than the antiseptic application of rigid logic. He must take emotional reactions into account—those of his crew and those of the primitive anthropoids. In the end, he prevails by taking a highly illogical gamble. But the action itself isn’t as important as the motivation behind it—a new willingness to entertain hunches and other emotional, human thinking. As story arcs go, this one is tiny; it would span about a centimeter. It takes a performance of masterful restraint and subtlety for it to register at all. Yet register it does, and as a result “The Galileo Seven” became a landmark early adventure. It explored the mind of Spock more deeply than any previous installment—and instantly became a fan favorite.

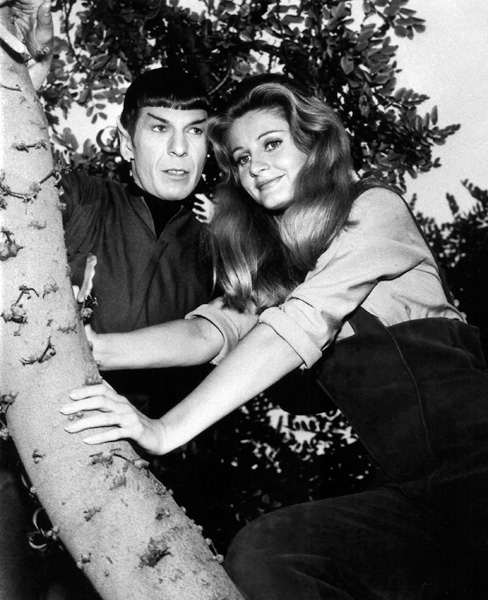

The Lovely Leila

Spock unwinds with Leila Kalomi (Jill Ireland) in “This Side of Paradise,” which features one of Nimoy’s most subtle and touching performances.

While visiting planet Omicron Ceti III, Spock is infected by spores from a plant that instills feelings of happiness and security. Under the influence of the spores, Spock falls in love with botanist Leila Kalomi (Jill Ireland), an old companion from his days on Earth. That’s the plot of the watershed “This Side of Paradise,” which is dotted with outstanding moments for Nimoy, who seems energized by this emotionally rich scenario. In the first of many memorable interludes, Spock falls to the ground after being sprayed by the spores. He writhes and groans in agony as his mind tries to fight the emotions swelling within him. Then suddenly, the fight is over. A smile creases his face. A contented-looking Spock takes Kalomi’s hand and says, “I love you. I can love you.” Nimoy’s voice is filled with more wonder than adoration, as the Vulcan experiences joy for the first time. In a subsequent scene with Kalomi, it was Nimoy’s idea for Spock to hang upside down in a tree, in a state of blissful abandon.

The key to the actor’s approach to Spock was its simplicity. Nimoy understood that, playing the austere Vulcan, even the slightest display of emotion—a raised eyebrow, a shift in posture or tone of voice—would be amplified a hundredfold in the minds of viewers. This technique is showcased perfectly in the climax of “This Side of Paradise.” Freed of the spores, Spock must break off his relationship with Kalomi—and in so doing, remove her from the infection-created reverie she has enjoyed on Omicron Ceti III. The stoic Spock simply allows Kalomi to realize that he has returned to his normal, logical self—and as a result, his love for her is gone. Nimoy’s tender, sad tone of voice—counterpointed by the actor’s stiff, straight-backed posture—suggests that the Vulcan secretly shares Kalomi’s heartache, even if he cannot express it, or even admit it to himself. Nimoy’s mournful reading of the episode’s final line says it all: “For the first time in my life, I was happy.”

Mind Meld with the Horta

The Vulcan Mind Meld, first seen in “Dagger of the Mind,” was invented by Gene Roddenberry as a device to speed up expository sequences. In later episodes, Spock melded with numerous entities—human, alien, and even mechanical—but the most memorable of these encounters remains Spock’s telepathic link with the Horta in screenwriter Gene L. Coon’s “The Devil in the Dark.” This is hardly one of Nimoy’s most refined performances; he moans, “Eternity ends! … The Chamber of the Ages! … The Altar of Tomorrow!” with nearly Shatnerian fervor. But this sequence (which runs just over six minutes, the series’ longest mind meld) is critical to the entire episode, which many fans rank among the show’s finest installments. This is the moment when Spock realizes that the murderous “monster” he and Kirk have been pursuing is actually a grieving mother trying to defend the lives of her unhatched offspring, which the miners of planet Janus IV have unwittingly killed by the thousands. Although perhaps a touch overplayed, this paradigm shift registers emphatically with audiences, whose sympathies switch from the besieged humans to the desperate Horta. Nimoy’s anguished delivery provides the conduit for, arguably, the most effective and moving of Star Trek’s many calls for understanding in the face of prejudice.

Blood Fever

Here’s another great episode and another great improvisation by Nimoy (or, if you prefer, from Spock). For Theodore Sturgeon’s “Amok Time,” which launched the series’ second season, Spock invented the split-fingered Vulcan salute to coincide with Sturgeon’s immortal line, “Live long and prosper.” Nimoy borrowed the hand sign from his Orthodox Jewish upbringing. It’s a gesture used by Jewish priests known as the Kohanim during the High Holiday services. “The hand, held in that shape, spells out the Hebrew letter Shin,” Nimoy explained in I Am Not Spock. “This is the first letter in the word Shadai, which is the name of the Almighty.” Like the endlessly quoted (and parodied) “Live long and prosper,” Nimoy’s Vulcan salute became another trademark, both for Spock and Star Trek in general.

However, Nimoy’s excellence in this episode extends well beyond the split-fingered hand sign. Once again, he seizes on the opportunity to visualize Spock’s inner conflicts. This time, the struggle is between his animalistic drive to reproduce and his rational desire to remain in control of his mind and body. Nimoy is superb throughout. He has an endearing scene with Nurse Chapel in Spock’s cabin. The nurse is heartsick with fear and longing for the ailing Vulcan, whom she secretly loves. “I had a most startling dream—you were trying to tell me something but I couldn’t hear you,” Nimoy says tenderly as Spock wipes a tear from Chapel’s eye. This whole sequence reverberates with unspoken sexual and romantic tension. As the episode progresses and Spock grows more and more sick, Nimoy’s performance gradually becomes more exaggerated. Later, Spock is able to calmly explain the rules of the koon-ut-kal-if-fee mating ritual to Kirk and McCoy but seems distracted, as if dazed or drugged. As Spock sinks deeper into the mental quagmire of the “plak tow” (“blood fever”), Nimoy walks robotically, his mouth hanging open. He seems physically as well as mentally staggered when his fiancée, T’Pring (Arlene Martel), refuses to marry him and calls for Spock to battle her chosen champion (Kirk). When asked if he accepts the challenge, Spock can’t even answer in words. Nimoy merely nods. His eyes roll back in his head. During the fight itself, Nimoy seems convincingly bent on murder. (In view of his ongoing, off-camera rivalry with Shatner, perhaps trying to kill Captain Kirk wasn’t much of a stretch for Nimoy!) However, his intimidating performance reminds audiences why, prior to Star Trek, he was frequently cast as a villain.

The Needs of the Many …

In Star Trek II: The Wrath of Khan, the dying Spock famously stated, “The needs of the many outweigh the needs of the few … or the one.” But Spock first voiced this logical imperative—less eloquently, perhaps—in episodes such as “The Galileo Seven,” in which Spock says, “It is more rational to sacrifice one life than six”; and “Journey to Babel,” in which Spock hesitates to save his father’s life out of his sense of responsibility to the Enterprise and its crew. “Babel” ranks among the best loved of all Star Trek episodes and features excellent performances by nearly the entire cast. Nimoy has a series of outstanding moments, playing opposite Mark Lenard (as Spock’s father, Sarek), Shatner, and DeForest Kelley. But the actor’s finest scene in this episode—and one of the most emotionally riveting sequences in all of Trek lore—is Spock’s tête-à-tête with his mother, Amanda (Jane Wyatt). She pleads with her son to relinquish command of the Enterprise (Kirk has been incapacitated by a would-be assassin) so Spock can donate the Vulcan blood needed for Sarek’s lifesaving heart operation. Spock emphasizes that he is now responsible for the lives of the ship’s crew and passengers, including more than a hundred dignitaries bound for a key diplomatic summit. The ship is under attack from an unknown enemy; he cannot risk hundreds of lives to save just one person, not even his father. Sarek, he insists, would agree with his logic. But Amanda does not agree. “Nothing is as important as your father’s life,” she says. This scene provides another outstanding example of Nimoy’s understated approach. “How can you have lived on Vulcan so long, married a Vulcan, raised a son on Vulcan, without understanding what it means to be Vulcan?” Spock asks. Nimoy stands straight, his arms neatly folded behind his back, betraying nothing. Yet his gentle tone of voice, with a slight quiver for emphasis, informs us that despite his apparent exasperation, he admires his mother’s devotion to Sarek; it makes him love her even more deeply—even though Amanda slaps her son across the face at the conclusion of the sequence.

Spock, flanked by his faithless fiancée T’Pring (Arlene Martel), flashes the Vulcan salute in this publicity photo from “Amok Time.” The hand sign was one of Nimoy’s famous improvisations.

By the middle of Star Trek’s second season, Nimoy and Spock were on such good terms they felt at ease leaving the friendly confines of the series to have a little fun on the town. Nimoy made a memorable guest appearance on The Carol Burnett Show in late 1967. In a skit titled “Mrs. Invisible Man,” Burnett played a confused young mother in search of parenting advice who mistakenly calls in Mr. Spock rather than famed pediatrician Dr. Spock. Nimoy appeared in full costume and makeup, poking good-natured fun at his famous alter ego.

Nimoy was dismayed by the drop-off in quality of teleplays (and everything else) during Star Trek’s final season and complained bitterly to producer Fred Freiberger that his character was stagnating in episodes such as “Spock’s Brain.” Nevertheless, Nimoy delivered outstanding work in numerous adventures, including “The Enterprise Incident,” in which Spock seduces a female Romulan commander (Joanne Linville) as part of a plot to capture the Romulan Cloaking Device; and “The Tholian Web,” in which a bereft Spock assumes command of the Enterprise following Kirk’s apparent death. Even subpar scripts couldn’t disconnect Nimoy from Spock. Or Spock from the hearts of fans.