28

The Unsung Heroism of DeForest Kelley

When I see the trade papers, after a whole season, still only list Bill Shatner and Leonard Nimoy as co-stars, I burn a little inside,” said DeForest Kelley, in a rare fit of candor with a TV Guide interviewer in 1968. “What I want, as a co-star, is to be counted in fully. I’ve had to fight for everything I’ve gotten at Star Trek, from a parking space at the studio to an unshared dressing room, and sometimes the patience wears raw.”

Kelley went on to grouse about the passive nature of his role as Dr. McCoy, compared to the dynamic Captain Kirk and Mr. Spock, and to express exasperation with his character being omitted from an unnamed teleplay (likely “Errand of Mercy”). “It was an oversight,” Kelley was told by the writer of the episode (probably Gene Coon). “An oversight!” Kelley bemoaned. “If a producer-writer on my own show forgets me, then I’ve got problems!”

The outburst was notable because, throughout his long association with Star Trek, Kelley’s talent was surpassed only by his professionalism. Among producers, directors, and fellow actors, he was the single best-liked and most-respected member of the cast, a skilled and dedicated craftsman who seldom complained about anything.

Nevertheless, the actor had every reason to gripe. Throughout Star Trek’s broadcast run, Kelley’s contributions to the show remained undervalued. He didn’t receive costar billing until Season Two, when his salary jumped from a meager $800 per episode to about $2,500 per episode, on par with Nimoy’s but still far less than Shatner’s $5,000. Even then, Kelley seldom garnered the kind of attention, in terms of interviews and public appearances, his costars enjoyed. For instance, Roddenberry tried to send all three of the show’s leads for a 1967 appearance on NBC’s Today Show, but was informed that Today only wanted Shatner and Nimoy. This was common; producers and event organizers didn’t consider Kelley a significant draw.

Yet the actor’s work was just as crucial to Star Trek as that of his costars. Kelley’s prickly-yet-warmhearted “old country doctor” helped humanize the series, widening its appeal by making its futuristic setting and gadgetry seem more familiar and approachable. Kelley’s superb, selfless performances in his many scenes with Shatner and Nimoy accounted for much of the program’s vaunted Kirk-Spock-McCoy chemistry. This beloved troika—with Kelley’s McCoy playing Tin Man to Shatner’s Lion and Nimoy’s Scarecrow—quickly emerged as one of the series’ most appealing features. Nimoy earned greater accolades, winning Emmy nominations in each of the show’s three seasons in his far flashier role. But Kelley—arguably—was the show’s most dependable player, delivering pitch-perfect performances in episode after episode, including the following classic adventures.

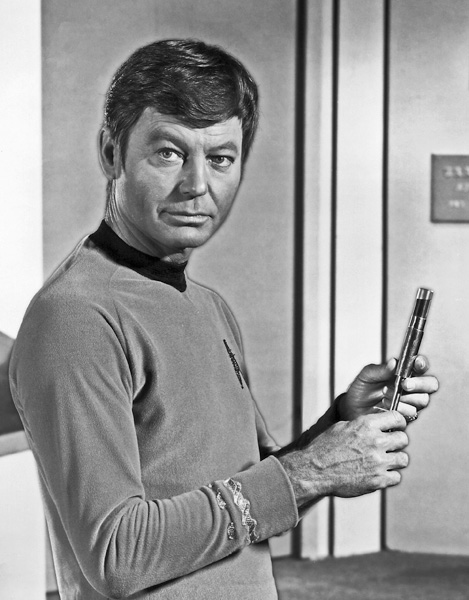

Kelley’s folksy charm as Dr. McCoy humanized the universe of Star Trek.

“The Empath”

It’s no wonder that Kelley named “The Empath” his favorite Star Trek episode. No single installment provides a more complete summation of all the actor’s formidable gifts. Kelley was blessed with wondrously expressive eyes. His voice—a Georgia drawl tempered by diction lessons during his tenure as a Paramount contract player in the 1940s—was distinctive yet supple, capable of shifting tone in mid-sentence, lilting or rasping as the material dictated. He was a fine dramatic actor who, unlike many fine dramatic actors, also possessed excellent comic timing.

All these attributes are showcased in “The Empath,” which also stands as the fullest expression of Dr. McCoy’s self-sacrificing devotion to his friends and to his calling as a physician. The teleplay—an unsolicited submission by a fan, Joyce Muskat, not a professional screenwriter—affords Kelley the opportunity to appear heroic, compassionate, and funny, sometimes simultaneously. In Muskat’s story, Kirk, Spock, and McCoy are taken prisoner by the inscrutable Vians; the captain and the doctor are tortured but later healed by a mute alien woman (Kathryn Hays) with empathic extrasensory powers.

Despite the away team’s incarceration, McCoy remains in good spirits early in the episode, when he nicknames the mute Empath “Gem.” (“It’s better than ‘Hey, You,’” McCoy reasons.) In this script, Kelley receives a heavy dose of the dry, expository dialogue usually reserved for Mr. Spock: McCoy must explain that Gem is a mute, how per powers work, and other background information. Fortunately, the actor’s folksy, easygoing delivery puts this material over convincingly, and even entertainingly. Kelley also delivers one of his signature catchphrases when McCoy derisively informs Spock that “I’m a doctor, not a coal miner.” But Kelley’s finest moments arrive toward the end of the tale. With Kirk recovering from grievous injuries, the Vians ask for a new torture subject. McCoy drugs Kirk and then Spock so that he, alone, is available to endure the punishment. Kelley’s earlier nonchalance gives way to quiet yet implacable determination as McCoy risks his life to preserve the well-being of his friends. Afterward, the doctor lies apparently dying on a table, attended by Mr. Spock. “You’ve got a good bedside manner, Spock,” Kelley utters in a thin whisper, as the doctor lapses into a coma. His eyes reveal the love his character feels, but seldom expresses, for his Vulcan friend. Moments like that one make “The Empath” the brightest of many shining moments for both the actor and his character.

“For the World Is Hollow and I Have Touched the Sky”

Most of the show’s cast, crew, and fans consider Star Trek’s third season a creative wasteland. But, at least for Kelley, Season Three also included the occasional artistic oasis. Some of his—and Dr. McCoy’s—best episodes originated in the series’ final year, including “The Empath,” “Spectre of the Gun,” “Day of the Dove,” and “For the World Is Hollow and I Have Touched the Sky.” The lattermost of that quartet, written by Rik Vollearts and directed by Tony Leader, is a melodramatic but imaginative yarn that puts Dr. McCoy center stage. The good doctor diagnoses himself with a terminal illness, goes on a dangerous away mission, falls in love, joins a cult, commits espionage and is tortured, escapes the cult, breaks up with his girlfriend, and is miraculously cured, all in the course of one fifty-minute episode. Somehow Kelley makes all this seem believable and even moving.

The actor’s performance is subtle and multilayered, conveying McCoy’s complex and conflicted emotions though carefully nuanced delivery and revealing facial expressions. When the doctor informs Captain Kirk that he has contracted “xenopolycythemia” and has less than a year to live, McCoy tries to appear chipper and upbeat, but Kelley’s eyes betray the character’s worry and fatigue. Later, the Enterprise investigates a mysterious planetoid, which turns out to be a massive, elaborately disguised spacecraft on a collision course with the densely populated planet Daran V. McCoy falls in love with Natrina (Katherine Woodville), the high priestess of the asteroid’s occupants, who do not realize they are on board a starship. Reluctantly at first, the dying McCoy decides to grasp this last chance at happiness. Kelley brings a tender, confessional quality to his romantic interludes with Woodville, in which McCoy describes his life as “very lonely.” McCoy renounces his Starfleet commission and joins Natrina’s cult, which worships the planetoid-ship’s nearly omniscient computer. But McCoy’s restless scientific curiosity prevents him from blindly following orders. Kelley again convincingly portrays churning, mixed emotions, as McCoy remains committed to Natrina yet itches to uncover the secrets of the giant spacecraft and help avert the tragedy of its impending collision with Daran V (which, of course, he does).

Like “The Empath,” “For the World Is Hollow” remains an outstanding entry for both Kelley and McCoy. However, with its downbeat storyline and dark tone, this is an unusually humorless episode, denying Kelley the opportunity to demonstrate the full spectrum of his abilities.

“Friday’s Child”

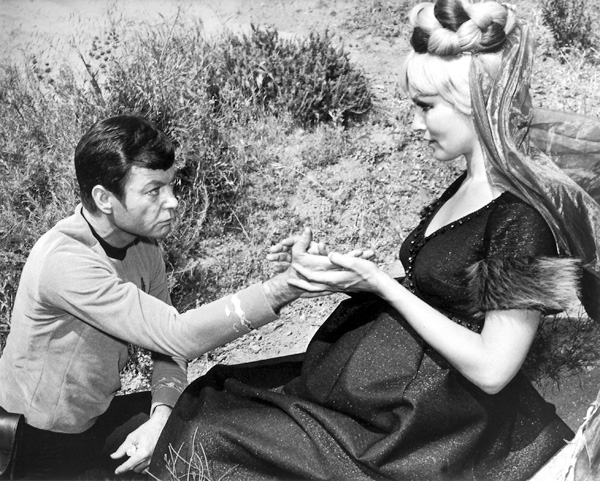

“Friday’s Child” places Kelley’s gift for comedy in the forefront, as he tends to the haughty Eleen (played by ex-Catwoman Julie Newmar).

Kelley enjoys a much livelier, wittier part in “Friday’s Child.” Although a less challenging assignment than either “The Empath” or “For the World Is Hollow,” Kelley’s charming performance here remains a delight. In this episode, Kirk, McCoy, and Spock find themselves trapped on planet Capella V, competing with the Klingon Empire to win a mining agreement from the planet’s warlike, preindustrial natives.

McCoy spends much of the episode caring for Eleen (Julie Newmar), a pregnant Capellan woman, the wife of a murdered chieftain who feels compelled by Capellan custom to sacrifice her life and that of her unborn child. McCoy must overcome Eleen’s cultural programming to not only deliver the baby but convince its mother that the child’s life—and her own—is worth saving. The good doctor accomplishes this in rather unorthodox ways, locking horns with the warrior-queen verbally and even physically. “Now let me see that arm!,” Kelley practically growls after Eleen accidentally burns herself. Later, when the Capellan patient slaps him, the doctor slaps her back. (When Kirk later notes that this technique isn’t covered in the Starfleet medical guide, McCoy counters, “It’s in mine from now on.”) This exchange finally earns McCoy Eleen’s respect, but as a result she gloms onto him and begins referring to her unborn baby as “our child,” much to the doctor’s consternation—and Kirk and Spock’s amusement. Kelley’s comedic slow burns in these sequences are hilarious. The story presents a few serious, dramatic moments for Kelley, as well, like when McCoy pleads for Eleen to accept her newborn son, who will perish without her. But for the most part the tone remains light. Kelley alone among the show’s cast could believably hold a baby and say, “Oochy-woochy-koochy-koo.” (Kirk explains to a puzzled Mr. Spock that McCoy is speaking in “an obscure Earth dialect. If you’re curious, consult Linguistics.”)

Prickly yet warmhearted, amusing yet with underlying gravitas, Kelley (as always) brings McCoy to vivid life in “Friday’s Child.” Appealing appearances like this one are what made the doctor one of the show’s most popular characters.

“Shore Leave”

Kelley’s flair for comedy must have come as a revelation to viewers accustomed to seeing the actor portray dastardly Western gunmen. Yet Star Trek’s screenwriters took advantage of Kelley’s comedic abilities from the outset. In the first nonpilot episode produced, “The Corbomite Maneuver,” Kelley was seem muttering to himself, “If I jumped every time a light came on around here, I’d wind up talking to myself.” Theodore Sturgeon’s lighthearted teleplay “Shore Leave” gave Kelley another highly entertaining, largely comedic role, this time with romantic overtones. And McCoy finally gets the girl.

The girl, in this case, is Yeoman Tania Barrows (Emily Banks), who, along with McCoy, Sulu, and a pair of other crewman, beams down to a beautiful, Earthlike, uninhabited planet for shore leave—only to be plagued by annoyances and dangers conjured up from their own memories and imaginations. McCoy mentions Alice in Wonderland and then sees a giant white rabbit with a pocket watch and a waistcoat disappear through a hole in a hedge; the rabbit is soon followed by a young blonde-haired girl in a blue dress. Kelley’s incredulous, mute reaction expresses consternation, amusement, fear, and a thousand other thoughts and feelings simultaneously. Later, McCoy romances Barrows, encouraging her to try on the Elizabethan gown of a storybook princess, which magically appears on a nearby shrub. When Barrows warns McCoy not to peek while she changes, Kelley counters: “My dear, I’m a doctor. When I peek, it’s in the line of duty.” When a black knight appears on horseback to challenge McCoy for Barrows’s honor, the brave physician (reasoning that none of these fantastic events could be real, so they must be an illusion) boldly stands his ground—and is run through with a lance. Kelley’s look of surprise and anguish as the lance strikes proves unsettlingly realistic. But McCoy returns, miraculously healed, for the episode’s finale. To Barrow’s irritation, he reappears with a fur-bikini-clad, Playboy Bunny–like showgirl on each arm. Clearly delighted with this resolution, Kelley flashes a beaming smile. The actor probably wished someone had written a few more “Shore Leave”–like adventures. Many fans would share that sentiment.

“Return of the Archons,” “The City on the Edge of Forever,” and “Day of the Dove”

Dr. McCoy was not only the most human, and in many respects most endearing, character on Star Trek but also the most vulnerable. He was not only older and more frail than the dashing, athletic Kirk or the superhuman Spock but more susceptible to outside influence. If the script called for a character to get drugged, duped, hypnotized, or possessed, that afflicted character would more than likely be McCoy, who always led with his heart. Such storylines supplied further evidence of Kelley’s apparently boundless versatility.

In “The Return of the Archons,” McCoy falls under the telepathic control of the supercomputer Landru—he’s “absorbed” into “The Body.” Kelley’s vacant smile and brainwashed demeanor (“Blessed be the body and health to all of its parts!”) at first borders on the comic, but later, when McCoy realizes that Kirk and Spock are only pretending to have been absorbed, the doctor’s steely-eyed denunciation of his former friends (“You’re not of the body! Traitors!”) is chilling.

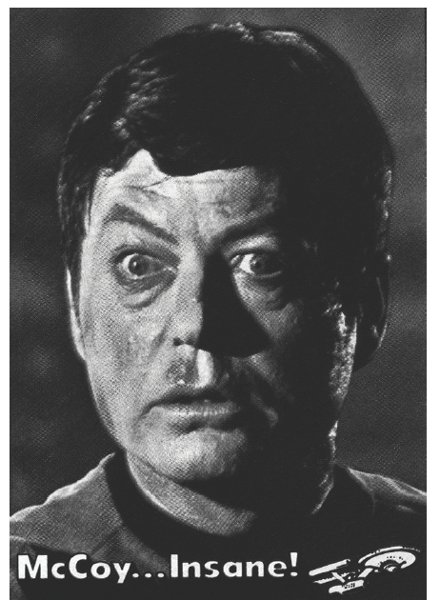

Kelley was unnervingly effective as the “insane McCoy” from “The City on the Edge of Forever,” as pictured on this 1976 Topps trading card.

In “The City on the Edge of Forever,” McCoy accidentally overdoses on a dangerous drug and temporarily becomes a raving madman. Although Kelley is off-screen for most of this classic adventure, he’s strikingly effective in his isolated scenes as the sweaty, delusional, paranoid McCoy. At one point, the doctor weeps in agony thinking about twentieth-century surgery (“needles and sutures … oh, the pain … to cut and sew people like garments!”). Kelley’s portrayal of the unbalanced McCoy reminded viewers why he was so good at playing crazed Western outlaws like Toby Jack Saunders from Apache Uprising. He seems fully capable of murder—or worse.

In “Day of the Dove,” McCoy (along with the rest of the crew) comes under the mental influence of a mysterious, hate-devouring life force that has trapped a platoon of Klingons on board the Enterprise. The human and Klingon factions fight for control of the ship, a bloody conflict staged with swords and daggers (which the hate-creature magically substituted for the ship’s more advanced weapons). Under the entity’s sway, McCoy begins spewing hate-speak: “Murderers, we should wipe out every last one of them!” Kelley’s impassioned delivery, with eyes blazing and voice full of gravel, makes the addled physician seem more dangerous than the Klingons.

Whenever McCoy was taken over by some alien force, which also happened in a handful of other adventures, Kelley could be counted on to deliver a distinctive, powerful portrayal, as demonstrated by his diverse yet uniformly excellent performances in these three episodes.

Other Outstanding Performances

About the only installments in which DeForest Kelley failed to perform with distinction were “Where No Man Has Gone Before,” “What are Little Girls Made Of?,” “The Menagerie, Part II,” and “Errand of Mercy.” That’s because he didn’t appear in those episode at all! Narrowing the actor’s best Star Trek work to a handful of adventures is nearly impossible. But a few other performances deserve mention:

• “The Man Trap,” the first episode broadcast, gave Kelley more screen time than most of the show’s early installments. The actor made the most of it, delivering a touching performance as McCoy encounters his lost love—Dr. Nancy Crater (Jeanne Bal), who turns out to be a shape-shifting salt vampire. Kelley’s heartfelt work helps elevate the episode to something (slightly) better than a typical sci-fi monster yarn.

• In “Miri,” Dr. McCoy devises a cure for a ghastly plague that has wiped out nearly the entire population of a planet, leaving only a clutch of orphaned children. Unwilling to risk anyone else’s life, he then injects himself with the untested, and potentially lethal, vaccine. Kelley’s sober, determined demeanor bolsters the credibility of this otherwise shaky episode.

• Almost everyone performs brilliantly in the classic “Journey to Babel,” in which Spock must be convinced to relinquish command of the Enterprise so he can donate blood for an operation to save his father’s life. Kelley earns high honors for his verbal battles with Spock, this time played for drama rather than comedy, as he strives to save the life of Ambassador Sarek (Mark Lenard).

• In “The Deadly Years,” in which McCoy and several more crew members contract an alien disease that causes hyper-accelerated aging, Kelley dabbles in self-parody. As the crotchety, elderly McCoy, Kelley exaggerates his character’s trademark speech patterns and mannerisms to highly amusing effect.

• “Spectre of the Gun,” an eerie, outer space retelling of The Gunfight at O.K. Corral, was written by Gene L. Coon specifically as a tribute to Kelley and his gunslinging past. It’s an enjoyable romp, with Kelley in fine fettle throughout.