31

Human Exceptionalism

Everything that is truest and best in all species of beings has been revealed by you. Those are the qualities that make a civilization worthy to survive.

—Vian scientist Lal (Alan Bergman) in “The Empath”

In the late 1960s, the near-utopian future imagined by Gene Roddenberry offered hope to viewers shaken by the Vietnam War, race riots, political assassinations, and cultural upheavals of all kinds.

This upbeat tone was bracingly different than most science fiction of the era, which tended toward the dystopian and apocalyptic. Consider these two revealing examples: Producer George Pal’s The Time Machine (1960), an update of H. G. Wells’s classic novel, predicted that a nuclear conflagration would occur by 1966 and forecast a future where mankind has split into two species—the sheeplike Eloi and the cannibalistic Morlocks. Hammer Films’ The Damned (1963), based on H. L. Lawrence’s 1960 novel The Children of Light, assumed not only that the world was teetering on the brink of Armageddon but that world leaders assumed the same thing. Its plot involved secret government experiments aimed at producing a race of radioactive children capable of surviving the inevitable holocaust. While otherwise very different, both of these tales took for granted that in order to survive, humanity will have to mutate into something no longer human. And these are just two of countless nihilistic stories published or filmed during the ’60s.

Star Trek stood in bold opposition to this prevailing pessimism. The cornerstone of the show’s radical optimism was Roddenberry’s unflagging confidence in the perfectibility of the human race. The show’s overriding message was that our species can and will overcome war, racism, and poverty, and that once those ancient evils are defeated, the stars are the limit.

“It isn’t all over; everything has not been invented,” Roddenberry told a TV Showpeople interviewer in 1975. “The human adventure is just beginning.”

This Is Only a Test

Roddenberry’s faith in humanity was expressed most clearly through several teleplays in which Enterprise crew members, functioning as representatives of the human race, are subjected to elaborate tests devised by more evolved or more technologically advanced beings. This was the basic premise of both Star Trek’s original pilot, “The Cage,” and the Star Trek: The Next Generation pilot, “Encounter at Farpoint,” among many other episodes. Time and again throughout the original seventy-nine Trek adventures, curious aliens took humanity’s measure and declared our species exceptional.

The Metrons—“Arena” is best remembered for Captain Kirk’s epic battle with the reptilian Gorn, but, thematically speaking, the Gorn remains the less important of the two species Kirk meets in this installment. More significant is his encounter with the Metrons, the race who force Kirk and the Gorn captain into a life-and-death struggle (with the fate of their respective starships in the balance) after the Enterprise pursues a Gorn cruiser into Metron space. After a cat-and-mouse struggle that consumes nearly half the episode’s running time, Kirk finally incapacitates the Gorn by building a cannon out of bamboo and rocks, MacGyver style. Over the course of the contest, the captain not only figures out how to fashion the weapon, but also overcomes his fear and loathing for the reptilian creature, whose soldiers wiped out a Federation outpost. Kirk surprises the Metrons by refusing to deliver the coup de grace to the fallen Gorn.

“By sparing your helpless enemy, who surely would have destroyed you, you demonstrated the advanced trait of mercy, something we hardly expected,” a Metron emissary informs the captain. “We feel there may be hope for your kind. Therefore, you will not be destroyed.” The alien goes so far as to suggest that perhaps humanity and the superadvanced Metrons may become friends—in another thousand years or so. “You’re still half savage, but there is hope,” the Metron declares.

During the final wrap-up on the Enterprise bridge, Kirk boasts to Spock, “We’re a most promising species, as predators go. Did you know that?”

“I frequently have my doubts,” Spock replies.

“I don’t, not anymore,” Kirk answers. “And maybe in a thousand years we’ll be able to prove it.”

Although “Arena” was written by Gene Coon (based on a short story by Fredric Brown), this closing sentiment could have come from Roddenberry’s own mouth. In fact, the producer echoed the idea nearly twenty years later at the ceremony unveiling his star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame in 1985. “I believe in humanity,” Roddenberry said. “We are an incredible species. We’re still just a child creature; we’re still being nasty to each other. And all children go through those phases. We’re growing up; we’re moving into adolescence now. When we grow up, man—we’re going to be something.”

The Melkotians—In “Spectre of the Gun,” acting on orders from Starfleet to make contact with the reclusive inhabitants of planet Melkot, the Enterprise ignores a telepathic warning to stay away and beams down a landing party. In retaliation, the xenophobic Melkotians force the away team to replay the Gunfight at the O.K. Corral—with the Earthmen cast in the role of the doomed Clanton gang. Once again the humans triumph but refuse to kill their adversaries (even though “Morgan Earp” apparently has killed Ensign Chekov). And once again, the aliens are surprised and deeply impressed.

“Captain Kirk, you did not kill. Is this the way of your people?” the Melkotians ask. After being assured that peace is the way of the Federation, the Melkotians extend an invitation: “Approach our planet and be welcome.”

During the wrap-up, Kirk admits to Spock that he wanted to kill the gunslinger who had seemed to murder Chekov. Yet he was able to resist taking revenge. When Spock wonders how humanity survived, Kirk says, “We overcame our instinct for violence.” Perhaps this may even be true someday. The magic of Star Trek is that the show at least conjures the possibility.

The Talosians—While the Metrons and Melkotians offered benedictions for humanity, the Talosians provided a backhanded compliment. In “The Cage” (and “The Menagerie”), these bubble-headed, telepathic aliens capture Captain Pike (Jeffrey Hunter) in hopes of breeding a race of human laborers to help them recapture the war-ravaged surface of planet Talos IV. But ultimately, after performing several tests and scouring data from the computer banks of the Enterprise, the Talosians determine that humans are unfit for the job. “We had not believed this possible,” a perplexed Talosian explains. “The customs and history of your race show a unique hatred of captivity. Even when it’s pleasant and benevolent, you prefer death. This makes you too violent and dangerous a species for our needs.”

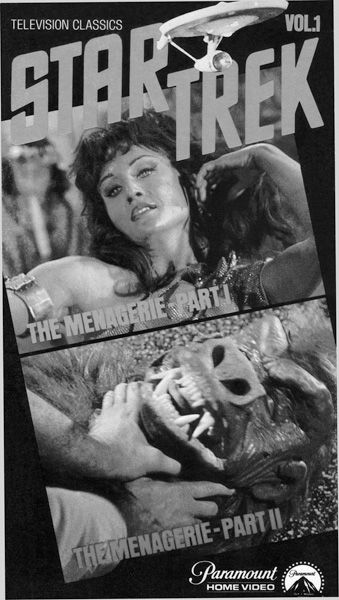

Early videotape packaging for “The Menagerie,” in which the Talosians test the human race (through the example of Captain Pike).

In other words, humans’ unquenchable thirst for freedom and steadfast resistance to oppression make them unfit for slavery. Guilty as charged, Your Honor.

The Excalbians—In “The Savage Curtain,” Kirk and Spock are lured to the surface of the planet Excalbia and forced to take part in a “drama” staged by its residents. The Excalbians, in order to learn about the human concepts of good and evil, stage an “Arena”-like battle in which Kirk and Spock fight alongside Abraham Lincoln and Surak of Vulcan against four fearsome adversaries, including Genghis Khan and Kahless the Unforgettable, founder of the Klingon Empire. As in “Arena,” the combatants are free to fabricate weapons from anything around them. Naturally, good wins over evil. But it’s a meaningless victory, at least according to the Excalbians. “You have failed to demonstrate for me any difference between your philosophies,” the alien explains. “Your good and your evil use the same methods, achieve the same results.”

The Excalbians fail to grasp the subtleties of the “drama” they just witnessed. It apparently means nothing to them that Kirk, Spock, Surak, and Honest Abe tried to make peace (Surak is killed trying to broker an agreement) and fought only as a last resort. The aliens also fail to grasp the significance of the combatants’ divergent motivations. While their adversaries competed for personal gain, Kirk’s team fought for the lives of the crew of the Enterprise, threatened by the Excalbians. Moreover, the aliens state flatly their belief that “the need to know new things” gives them the right to force other species to participate in such potentially fatal “spectacles.”

The aliens may not understand, but viewers certainly get the message: Not only is good superior to evil, but humans are superior to Excalbians, at least morally speaking.

Others—A few more episodes operate on the same wavelength. In “The Corbomite Maneuver,” Balok, a mysterious alien in a giant spaceship, toys with the Enterprise to test the character of its people and the mettle of its commander. But the exercise turns out to be an elaborate jest. Balok was merely seeking a congenial traveling companion. In “The Empath,” it’s not the humans but rather a mute woman with psychic powers who is being tested. The Vians capture and torture Kirk, Spock, and McCoy in hopes that the shining example of humanity will inspire the Empath, whom McCoy nicknames “Gem.” Finally, in the animated adventure “The Magicks of Magus-Tu,” humanity is placed on trial—literally—in a sort of reverse Devil and Daniel Webster scenario—by a species of demonic-looking aliens. As always, the essential goodness of human beings is confirmed.

Rage Against the Machines

Kirk confronts NOMAD, one of Star Trek’s many mechanical menaces, on the cover of this videotape release of “The Changeling.”

The future Roddenberry envisioned was predicated on the development of fantastic technologies: warp drive, enabling faster-than-light space travel; the transporter, initiating the near-instantaneous (and pollution-free) teleportation of people and goods; the replicator, which produces food from basic molecules; as well as medical advances, including the cure of most known diseases. Any of these breakthroughs would signal dramatic shifts in the social and political order of our world. A civilization in possession of all four could eradicate poverty, famine, and disease; renew our planet’s damaged ecology; and set out to explore the galaxy—just like on Star Trek. While these Treknological wonders were introduced as story devices, they also serve as testaments to Roddenberry’s faith in the potential of human intellect.

Yet Trek also displayed wariness toward such mechanical marvels, exemplified by Dr. McCoy’s distaste for the transporter. Such skepticism might seem out of place in Roddenberry’s twenty-third-century techno-utopia, but this was merely an alternate expression of the program’s guiding humanism. Repeatedly the series emphasized that the key to a long and prosperous future lies in improving ourselves (through peaceful cooperation and the eradication of racism, for instance), not in building better machines.

Several teleplays reminded viewers that technology exists to serve humankind—not the other way around. The Enterprise often encountered cultures where artificial intelligences lorded over human beings; Captain Kirk and his cohorts never failed to overthrow these mechanical tyrants. Even faulty human leadership was deemed superior to that of the most capable and benevolent computers. This follows logically, since in the universe of Star Trek nothing can be greater than humanity itself.

Computers in Command—“The Ultimate Computer” remains the most straightforward of these storylines, delivering its prohuman message with admirable directness. The Enterprise is chosen to test the experimental M-5 computer, supposedly capable of handling all aspects of starship command, up to and including battle. If successful, the M-5 will revolutionize space travel—and make starship captains obsolete, a prospect that disturbs Kirk, McCoy, and even, surprisingly, Spock. “Computers make excellent and efficient servants, but I have no wish to serve under them,” the Vulcan states.

The storyline plays out like a variation on the theme of the Legend of John Henry, with Kirk standing in for the hammer-swinging African American folk hero and the M-5 serving as the twenty-third-century equivalent of the steam-powered drill. “There are certain things men must do to remain men,” Kirk insists, a line that recalls the lyrics of the well-known folk song about John Henry (“Did the Lord say that machines ought to take the place of livin’?”).

At first the M-5 performs commendably, but eventually the unit goes haywire and destroys a Federation starship. Kirk, Spock, and Scotty mount a desperate effort to return the Enterprise to human command before more lives are lost. When the stardust settles, the M-5 is out of commission and its creator is being hauled away to the interstellar loony bin. For all its superhuman efficiency, the computer lacked one element essential for any leader of men. “Compassion,” McCoy ruminates. “That’s the one thing no machine ever had. Maybe it’s the one thing that keeps men ahead of them.”

However, in its travels across the galaxy, the Enterprise encountered numerous colonies or civilizations that had made the fatal error of ceding control to soulless machines. In “Spock’s Brain,” the citizens of Sigma Draconis VI regress to childlike ignorance under the rule of a cybernetic supercomputer. In “The Gamesters of Triskelion,” three disembodied brains, now plugged into a computer console, force a planet full of living beings to compete in gladiatorial contests. In “What Are Little Girls Made Of,” a noble scientist becomes an unfeeling monster when he transfers his mind into an android body. In “A Taste of Armageddon,” computers sanitize war to such an extent that it becomes a palatable proposition, continuing for hundreds of years and claiming billions of lives. And in “The Return of the Archons,” “The Apple,” and “For the World Is Hollow and I Have Touched the Sky,” computers are worshiped like gods (more on that in the following chapter). On a lighter note, Harry Mudd’s attempt to escape his shrewish flesh-and-blood wife and surround himself with beautiful androids goes comically awry in “I, Mudd.” And even the usually reliable Enterprise computer runs amok in the animated episode “The Practical Joker.”

Killer Machines—Not only must humans refuse to submit to computer control, but they must retain mastery of their machines. That was the lesson of “The Changeling” and “The Doomsday Machine,” in which powerful robots are loosed by their creators, with devastating consequences.

In “The Changeling,” NOMAD, a twentieth-century space probe, is damaged in a collision with an alien satellite and emerges with greatly enhanced capabilities and warped programming. Its new mission is to seek out perfect life forms and to destroy all imperfect ones. Since nobody’s perfect, this means NOMAD wipes out every living thing it encounters—until it meets the Enterprise and mistakes Kirk for its creator, Dr. Jackson Roykirk. Eventually, by pointing out NOMAD’s error, Kirk is able to induce the probe to commit suicide. Apparently this was the captain’s preferred method of dispatching dangerous mechanical adversaries. He uses the same trick in “The Return of the Archons,” “I, Mudd,” “What Are Little Girls Made Of?,” and “The Ultimate Computer.”

It takes more than mere words to vanquish “The Doomsday Machine,” a giant, nearly indestructible, planet-eating robot. The sacrifice of a crippled starship—the USS Constellation—is required to stop the device, a superweapon launched during a long-forgotten war and still wreaking destruction. In “That Which Survives” and “Shore Leave” (and even more pointedly in the animated “Shore Leave” sequel “Once Upon a Planet”), apparently inexplicable events that threaten the safety of the Enterprise and its crew are revealed to be the work of superpowered computers left to run without adequate oversight. Throughout the galaxy, it seemed, danger lurked wherever people failed to keep their technology on a proper leash.

Although Roddenberry’s humanism remained a constant, later Star Trek series backed off this man-over-machine element of the show’s message. This softening is exemplified by Commander Data from The Next Generation and the Doctor from Voyager. Both of these artificial life forms—an android and a hologram, respectively—were worthy to be called “human” in a larger sense of the word. In fact, one of Next Gen’s most memorable installments (“The Measure of a Man”) devoted itself to proving that Data was a sentient being, with human rights, to be treated with human dignity.

Human beings are inherently good and are capable of wondrous achievements. Humanity can never be replaced or mechanized. These two interrelated themes recur in at least 17 of the original seventy-nine episodes. It could be argued that the series’ humanism finds some form of expression in every installment. Moreover, through its consistent depiction of human beings at their best, Star Trek’s optimistic spirit took on a more intimate dimension, serving its audience as a sort of weekly (or, in syndication, daily) affirmation. In From Sawdust to Stardust, a biography of DeForest Kelley, author Terry Lee Rioux sums up the show’s message as “You are better than you think you are.”

That was something audiences of the 1960s yearned to hear. And it’s a message that continues to reassure viewers.