33

The Corrosive Power of Hate

Give up your hate! … You must both end up dead if you don’t stop hating!

—James T. Kirk, “Let That Be Your Last Battlefield”

Gene Roddenberry hoped to tackle social issues with his first television series, the peacetime military drama The Lieutenant (1963–64). But those aspirations were dashed by the Marine Corps (shot at Camp Pendleton, the show carried a USMC seal of approval) and wary network executives, who steered the program away from controversial subject matter, especially if the topic reflected poorly on the military. In frustration, Roddenberry turned to science fiction. For him, Star Trek’s primary function was to address political and moral issues through the lens of fantasy, as Jonathan Swift had done with Gulliver’s Travels. The show was not only Roddenberry’s vision of the future but also his vehicle for commentary on the present.

Consequently, Star Trek took on several hot-button topics, albeit in allegorical terms. Deciphering the parallels between the universe of Star Trek and the real world became a kind of parlor game among fans: The Federation represented the United States, the Klingons stood in for the Soviets, the Romulans equated to the Chinese, and so on. This wasn’t a particularly difficult pastime, since Star Trek’s messages usually were thinly veiled. While it often lacked subtlety, however, the series never lacked courage. Trek backed away from none of the controversial issues of the day, confronting segregation, the Vietnam War, the Cold War, women’s liberation, and other topics head-on. Ultimately, Star Trek’s politics could be boiled down to a single statement: Hate is toxic. It poisons all who possess it and destroys everything it touches, like slow-working acid. The program reiterated this simple yet truthful and (sadly) ever-relevant idea in numerous episodes.

Infinite Diversity in Infinite Combinations

Segregation remained an explosive issue throughout Star Trek’s broadcast life. Even though the U.S. Supreme Court had banned “separate but equal” schools in its Brown v. Board of Education ruling in 1954, public schools in Mississippi remained segregated until 1969. In many states, it remained illegal for blacks and whites to marry until the U.S. Supreme Court struck down antimiscegenation laws in June 1967, between Seasons One and Two of Trek. Race riots gripped several major American cities in the summer of 1967. In April 1968, shortly after the conclusion of Star Trek’s second season, Martin Luther King Jr. was assassinated, unleashing another wave of riots. The following week, President Lyndon B. Johnson signed the Civil Rights Act of 1968, which forbade racial discrimination in housing.

On the topic of race relations, Star Trek wore its politics on its sleeve. The composition of the Enterprise crew—with men and women of many different races and nationalities, and even different species, working side by side in mutual respect—renounced segregation in a subtle but unmistakable, ever-present manner. But merely placing Uhura and Sulu on the bridge wasn’t enough for Roddenberry. His series frequently confronted bigotry directly.

Former Riddler Frank Gorshin guest starred as Bele in “Let That Be Your Last Battlefield,” Star Trek’s most overt attack on racism.

That was the case with “Let That Be Your Last Battlefield,” which delivers its antiracism message with all the force of (and about as much subtlety as) a ball peen hammer. The Enterprise apprehends Lokai (Lou Antonio), an alien traveling in a stolen shuttlecraft. The fugitive’s physical appearance is remarkable: black on one side, white on the other. Shortly afterward, a similarly bicolored alien, Bele (Frank Gorshin), arrives and attempts to take custody of the prisoner, who he claims is a terrorist and mass murderer from the distant planet Cheron. Lokai claims to be a member of a race of former slaves now fighting for equality. He requests political asylum. However, both aliens seem trapped in the entrenched racism of the Cheron culture. Lokai ventures that “you monotone humans are just alike.” Later, Bele dismisses humankind as “mono-colored trash.” Racial bias is the root of the conflict between Lokai’s people and Bele’s people, as Bele states flatly.

“It is clear to even the most simple-minded observer that Lokai is of an inferior breed,” Bele proclaims. When Spock protests that Bele and Lokai appear to be of the same race, Bele balks. “Are you blind, Mr. Spock? Look at me. I’m black on the right side. … Lokai is white on the right side, all his people are white on the right side.”

This priceless moment nearly redeems the entire (otherwise slow-moving and heavy-handed) episode with its delightful satirical absurdity. Instantly the Cherons are reduced to the level of Dr. Seuss’s Sneetches (star-bellied and otherwise) from the classic children’s story. “Last Battlefield” draws an overt parallel with the American civil rights movement when Chekov comments that “there was persecution on Earth once. I remember reading about it in my history class.” Sulu replies, “Yes, but it happened way back in the twentieth century. There’s no such primitive thinking today.”

Lokai and Bele, however, remain locked in their racial animus. When Spock refers to them as “two irrevocably hostile humanoids,” Scotty suggests a more succinct term: “Disgusting is what I call them.” Eventually, Bele forces the Enterprise to return to Cheron, only to discover that the entire population of the planet is dead. The two races have totally annihilated one another. Nevertheless Lokai and Bele beam down to their home world to continue their feud amid the ruins of their civilization and the unburied bodies of their slain brothers and sisters.

But before they leave, Kirk urges the two to make peace. “Give up your hate!” he pleads. “Listen to me, you both must end up dead if you don’t stop hating.” His plea is to no avail. “You’re an idealistic dreamer,” Lokai says dismissively. True enough. Star Trek was made proudly by idealistic dreamers, and “Let That Be Your Last Battlefield” remains the program’s most uncompromising attack on racial intolerance.

It was hardly the show’s only such assault, however. “Is There in Truth No Beauty?” introduced the Vulcan philosophy of IDIC (Infinite Diversity in Infinite Combinations), a phrase that perfectly encapsulates the show’s advocacy for tolerance and inclusion. “Plato’s Stepchildren,” an otherwise humdrum installment, boasted a pair of remarkable features: the first interracial kiss in TV history (between Kirk and Uhura, at the command of tyrannical telepathic aliens) and a subplot involving a dwarf, Alexander (Michael Dunn), tormented due to his stature and lack of psychic powers. “Alexander, where I come from, size, shape or color makes no difference,” Kirk explains.

“Day of the Dove” and “The Cloud Minders” also tackled issues of prejudice from different angles. In “Day of the Dove” a noncorporeal, hate-eating life force stokes xenophobic animosity between humans and Klingons trapped together aboard the Enterprise. In “The Cloud Minders,” racism and classism merge in the plight of the working-class, subterranean Troglytes, who are exploited by the haughty denizens of Stratos, a floating city in the clouds. “Is There in Truth No Beauty?” challenged racist/species-ist standards of beauty. But “The Devil in the Dark” offered the series’ most deftly crafted and poetic argument for interracial (even interspecies) dialogue and understanding. The Horta, a tunneling alien creature that has killed dozens of miners and seems bent on the destruction of a mining colony on planet Janus VI, turns out to be a misunderstood mother protecting her unhatched young. Eventually a compromise is struck that enables humans and Horta to coexist peaceably and profitably. Issues of fairness and tolerance are raised, at least in passing, in numerous other adventures as well.

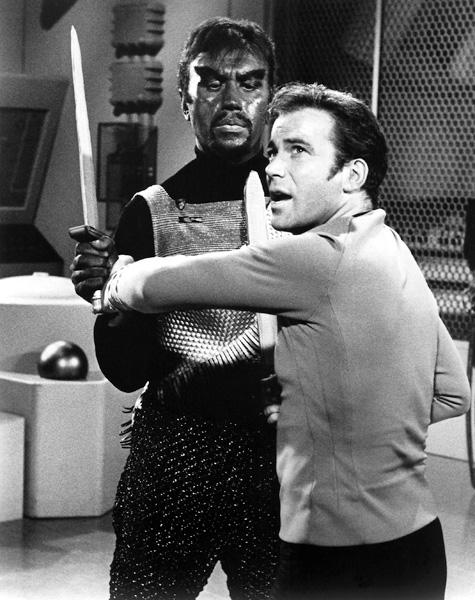

Kirk and Kang (Michael Ansara) battle each other before joining forces against a hate-devouring life force in “Day of the Dove.”

War (What Is It Good For?)

Star Trek’s attitude toward another major political issue of the era, the Vietnam War, was considerably more nuanced than its straightforward stance on segregation. Roddenberry’s secretary, Susan Sackett, claims that the Prime Directive (not to interfere in developing cultures) was intended as a subtle rebuke of U.S. policy in Southeast Asia. But if so, then it was too subtle, especially since Captain Kirk’s attitude toward the General Order Number One (as the directive was formally known) seemed uncertain; he violated it on several occasions. Also indicative of the program’s ambivalence about the war was Kirk’s tendency to say “We come in peace” while pointing a phaser. Created by a World War II veteran, and with numerous other vets in key roles both in front of and behind the camera, Star Trek, despite its progressive ideals, was hardly a stronghold for peaceniks. The show’s attitude seemed to be that war was something to be prevented if possible (several storylines involved Kirk and Spock trying to avert interplanetary conflicts) but not to be avoided at any cost.

The series’ clearest response to Vietnam was “A Private Little War,” written by Roddenberry from a story by Don Ingalls. Ingalls is credited under a pseudonym (“Jud Crucis”) because he was displeased with Roddenberry’s extensive reworking of his material. In its original form, Ingalls’s scenario was even more blatantly about Vietnam and mentioned North Vietnamese leader Ho Chi Minh by name.

While conducting a biological survey mission to Neural, a world where the natives have only recently developed metallurgy, Kirk and Spock find that the previously peaceful, primitive natives are now armed with flintlock rifles and engaged in a civil war. This represents a highly unlikely leap forward in technology and a jarring shift in culture. Kirk suspects that the Klingons, who covet the planet’s natural resources, may be arming the planet’s city dwellers and fomenting conflict with its Hill People. When this is confirmed, Kirk decides to even the score by arming the Hill People as well.

“A Private Little War,” one of the hardest-hitting of all Trek episodes, evidences a clear distaste for violence. “I thought my people would grow tired of killing, but you were right. They see it is easier than trading and it has pleasures,” the leader of the city folk tells his Klingon contact, chillingly. Meanwhile, the transformation of Hill People leader Tyree (Michael Witney) from gentle pacifist to bloodthirsty warrior is deeply unsettling. When Tyree picks up a rifle and declares, “I will kill them!,” Kirk winces. Nevertheless, the episode advocates interventionism, arguing that military involvement in places like Neural (or Vietnam) is sometimes a necessary evil. McCoy is reluctant to accept this.

“You’re condemning this whole planet to a war that may never end,” he says. Not coincidentally, when “A Private Little War” premiered on Groundhog Day of 1968, the U.S. military was entering its seventh year of action in Vietnam, where civil war would continue until 1975. “It could go on for year after year, massacre after massacre,” McCoy says, parroting the argument many in the antiwar movement were making in the late ’60s.

Nevertheless, Kirk insists on establishing “a balance of power.” It’s “the trickiest, most difficult, dirtiest game of all, but the only one that preserves both sides,” he says. Ironically, Kirk’s argument for war is rooted in compassion (the desire to preserve these two rival cultures), not hatred.

“Liberty and Freedom Have to Be More Than Just Words”

Kirk’s use of the phrase “balance of power” invokes American policy toward the Soviet Union in the 1960s. Inevitably, Star Trek had its say on the Cold War, as well. Roddenberry himself penned the episode’s most overt treatment of the subject, “The Omega Glory.”

An away team consisting of Kirk, Spock, McCoy and a redshirt security officer are trapped on the surface of planet Omega IV, infected with a potentially deadly virus and trapped in the middle of a civil war between the Asian-featured Kahms and the Caucasian Yangs. To make matters worse, Captain Ron Tracey (Morgan Woodward) of the Starship Exeter has violated the Prime Directive and intervened on the part of the Kahms. These story threads build to a far-fetched climax (“punch line” may be the more apt term) in which Omega IV is revealed to be a parallel Earth, where the Yankees (or “Yangs”) fought a biological war against the Commies (or “Kahms”), bombing one another into a savage, preindustrial condition. The Yangs even possess a tattered American flag and a copy of the U.S. Constitution, which they worship blindly. The Yangs win the centuries-old war but have lost all understanding of the ideals they originally fought to defend. Kirk tries to enlighten them with a bombastic, Shatnerian reading of the preamble to the Constitution. Afterwards, McCoy wonders if Kirk’s oratory also violates General Order Number One. “We merely showed them the meaning of what they’ve been fighting for,” Kirk says. “Liberty and freedom have to be more than just words.”

Although widely considered one of the series’ weakest entries, “The Omega Glory” delivers its message in unequivocal terms: Freedom is worth defending, but its defenders must not sacrifice their own freedoms to achieve victory. The story is pro-Cold War but also anti-McCarthyism. Additionally, the war-ravaged setting of Omega IV illustrates the folly of waging a global war with weapons of mass destruction.

Star Trek also addressed the Cold War through the makeup of its bridge crew, adding navigator Pavel Chekov at the start of Season Two. His mere presence signaled confidence that Americans and Soviets could and eventually would overcome their differences—something not readily apparent in 1967.

The subject of war—or its aversion—remains central to several other episodes. In “Friday’s Child,” Kirk finds the Klingons once again meddling in the internal politics of a developing world, instigating tribal unrest on planet Capella IV. As in “A Private Little War,” Kirk and Spock must set things right or else ignite an interplanetary war. In “Elaan of Troyius,” Kirk spends most of the episode trying to prepare a petulant, uncouth warrior princess for an interspecies marriage that will secure peace between two rival worlds. In “The Savage Curtain,” Kirk and Spock (not to mention Abe Lincoln and Surak of Vulcan) battle a quartet of interstellar supervillains (including Genghis Khan and Kahless the Unforgettable, founder of the Klingon Empire), but only after exhausting every possibility of making peace.

On the other hand, in “Errand of Mercy,” Kirk seems to be spoiling for a fight. He becomes exasperated with the pacifist Organians’ unwillingness to resist when the Klingons invade their planet. Finally, the Organians reveal hidden powers that enable them to repel the invaders—and quash a just-declared war between the Federation and the Empire. After spending most of the episode trying to goad the Organians into action, Kirk is brought up short when they intervene, preventing the humans and Klingons from settling their differences among themselves. “We have a right …” he begins. “To wage war, Captain?” asks the Organian elder (John Abbott). “To kill millions of innocent people? To destroy life on a planetary scale? Is that what you’re defending?” If it’s hard to square Kirk’s attitude in “Errand of Mercy” with his actions in other episodes, this is merely indicative of Star Trek’s mixed emotions on the subject of war.

A Balance of Terrors

Another expression of hate—the thirst for revenge—is the subject of several Star Trek episodes as well, including “The Doomsday Machine,” in which Commodore Matt Decker (William Windom) nearly destroys the Enterprise trying to strike back at the giant, planet-eating robot that consumed his crew; “The Conscience of the King,” in which a crewman thirsts for vengeance against a war criminal who murdered his parents (and thousands of other civilians); “Obsession,” in which Kirk questions his own motivations for delaying a vital, lifesaving mission to attack an alien creature that years earlier killed his mentor; and “The Alternative Factor,” which features an alien locked in a perpetual struggle with his alter ego from a parallel universe.

The subjects of vengeance, racism, and war converge in a single narrative with “The Balance of Terror,” one of the most brilliantly written and performed of all Trek adventures. The Enterprise swings into action when a cloaked Romulan war bird devastates several Federation outposts along the Neutral Zone separating Federation and Romulan space. A cat-and-mouse battle ensues, with Kirk matching wits with a skilled but battle-weary imperial commander (Mark Lenard). The primary theme of the episode is the horrific waste of life brought by war, personified in the death of a young crewman on what was supposed to be his wedding day. Kirk tries desperately to avert war, while his unnamed Romulan counterpart remains glumly resigned to it. “Our gift to the homeland, another war,” he muses. “Must it always be so? How many comrades have we lost in this way?”

A subplot involving the Enterprise’s navigator, Lieutenant Stiles (Paul Comi), brings both revenge and racism into the story. Stiles’s parents, he reveals, were killed in an earlier attack by the Romulans. He wants revenge, but Kirk insists the previous conflict was “their war, Mister Stiles, not yours.” Later, when the Romulans are revealed to have Vulcan-like features, Stiles immediately grows suspicious of Spock. Based on the first officer’s physical appearance alone, Stiles believes the Vulcan may be a Romulan spy. Again, Kirk forcefully rejects this idea. “Leave any bigotry in your quarters,” he says. “There’s no room for it on the bridge.” (Seated next to Lieutenant Stiles is George Takei, who spent his childhood in a World War II internment camp because many Americans thought like Stiles.) One of this episode’s most touching features is the growing respect and admiration between Kirk and the Romulan commander, which the Romulan acknowledges in a transmission to the Enterprise: “You and I are of a kind. In a different reality, I could have called you friend.”

Friendship: That’s the antitoxin for hate prescribed by Star Trek in many of these same episodes. Or perhaps it’s something greater than simple friendship—fraternity. Having experienced the “Band of Brothers” spirit in action during World War II, Roddenberry envisioned a similar experience for humanity as a whole: People from many backgrounds and of many races joining together in bonds of brotherly love, united in a common cause that elevates everyone involved—making the group stronger than the sum of its parts and bringing out the finest in every person. It may sound corny, but that’s the way Starfleet operates, and it’s the way Roddenberry believed the world would work—someday.