34

What Are Little Girls Made Of?

The Gender Politics of Star Trek

Worlds may change, galaxies disintegrate, but a woman always remains a woman.

—James T. Kirk, “The Conscience of the King”

Star Trek offered the soaring vision of a future free from prejudice, with men and women of all races and nationalities working side by side in mutual respect for the common good. But the program didn’t always live up to its lofty ideals, especially in its treatment of female characters. Although Gene Roddenberry considered himself a feminist, many feminists have questioned his understanding of the term or the sincerity of his commitment to the cause. It’s easy to see why. At times the disconnect between the show’s guiding principles and its individual teleplays could be glaring. Consider these examples:

• “Spock, the women on your planet are logical,” Kirk declares in “Elaan of Troyius. “No other planet in the galaxy can make that claim.”

• In “The Changeling,” NOMAD describes human females as “a mass of conflicting impulses.”

• In “Wolf in the Fold,” it’s explained that the fear-eating life force known as Redjac preys on females because they frighten more easily than males. (This apparently applies to women of all species and from many planets.)

• “I have never understood the female capacity to avoid a direct answer to any question,” Spock complains in “This Side of Paradise.”

In these and numerous other moments Star Trek seems embarrassingly chauvinistic. Often women are treated more as art objects than flesh-and-blood characters or depicted as emotionally unstable and unfit for command. Clearly, despite Roddenberry’s “feminism,” the show’s gender politics were complex and conflicted.

Although he espoused progressive social and political views consistently throughout his life, and made a concerted effort to portray a racially integrated Starfleet, Roddenberry blew the chance to depict a post-sexism future. In an essay published on the Sixties City pop culture website, author J. William Snyder writes that “Star Trek’s portrayal of women was … at best, ambivalent—wavering between an implicit belief in women as equals but an unwillingness to exemplify, in a tangible way, what was being professed.” This is a keen observation. However, it may not have been a lack of will but rather a lack of vision that prevented the show from better realizing its feminist convictions. Created by a man born in 1921, and written mostly by men of the same generation, Star Trek seemed incapable of looking beyond the patriarchal culture of mid-twentieth-century America, the world in which its creators had been raised. As a result, the program reinforced traditional gender roles and social structures. It was a man’s galaxy.

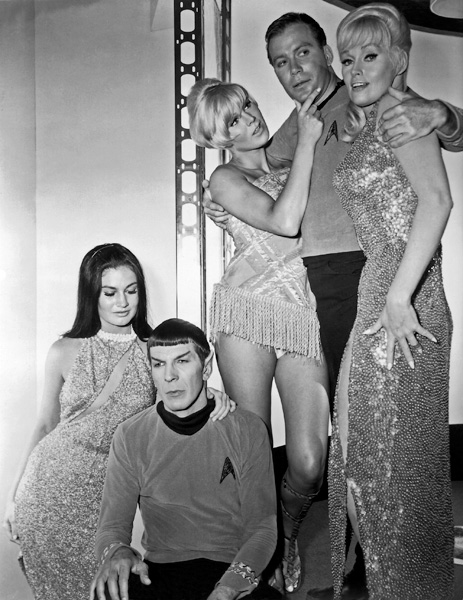

Spock and Kirk pose alongside “Mudd’s Women” (played by, from left to right, Maggie Thrett, Susan Denberg, and Karen Steele) in this press shot.

Starfleet’s Glass Ceiling

This reflexive reversion to patriarchy was expressed most visibly in Star Trek’s dearth of female leaders. In the utopian meritocracy that Starfleet is purported to be, given that the majority of the human population is female, more women should serve as captains and admirals than men, or at least an equal number. Anything less would indicate the persistence of prejudice that humankind has supposedly evolved beyond. Yet, as viewers learn in “Turnabout Intruder,” Starfleet has no female commanders at all! Although women serve the Federation as diplomats, scientists, and in other important capacities, there are no female captains.

The only woman ever seen in charge of a Federation starship is First Officer Number One (Majel Barrett) in “The Cage” (and “The Menagerie”), whose icy persona and gender-neutral non-name not only defeminizes her but nearly dehumanizes her. Captain Pike even complains to her (about Yeoman Colt), “I can’t get used to having a woman on the bridge. … No offense, Lieutenant. You’re different, of course.” Of course, there are female bridge officers, most notably Lieutenant Uhura, but Kirk never leaves the Enterprise under their command. Other than Uhura, the ship’s most prominent female crew members were the ever-servile Nurse Christine Chapel and Yeoman Janice Rand, whose primary duty seemed to be delivering food and beverages to Captain Kirk like some interstellar Hooters Girl.

“Turnabout Intruder,” the series’ final episode, throws these shortcomings into sharp relief. Exo-archeologist Dr. Janice Lester (Sandra Smith), a former lover of Kirk’s from his days at the Academy, uses an alien device to switch bodies with the captain. Lester is bent on settling old scores—one with Kirk, who dumped her, and one with Starfleet, who rejected her bid for command. “Your world of starship captains doesn’t admit women,” Lester seethes. Yet her actions seem to validate the wisdom of Starfleet’s glass ceiling. Masquerading as Kirk, Lester’s (female) leadership proves so flaky and temperamental that she can’t get through a single duty shift without giving herself away. She issues a series of irrational, contradictory orders and snaps at anyone who suggests a more logical course of action, including Spock. After less than a day on the job, she’s asked to report to sick bay to have her head examined. McCoy wants to run tests on the captain due to “emotional instability and irrational mental attitudes.”

McCoy isn’t the only one with doubts. “Doctor, I’ve seen the captain feverish, sick, drunk, delirious, terrified, overjoyed, boiling mad,” Scotty says. “But up to now I have never seen him red-faced with hysteria.” Meanwhile, Lester (that is, Kirk-in-Lester’s-body) tries to convince Spock, McCoy, and anyone else who will listen that she (he) is the real captain. Finally, Spock, McCoy, and Scotty mount a full-scale mutiny to remove their feminized leader, switch the “life forces” of Lester and Kirk back to their appropriate receptacles, and return a man to the captain’s chair.

“Turnabout Intruder” is a substandard episode in most respects—Shatner’s amusingly prissy performance as Lester-inhabiting-Kirk, and Smith’s dead-on Shatner imitation as Kirk-inhabiting-Lester provide the only points of interest—but the inherent sexism of Herb Wallerstein’s teleplay remains its most appalling feature. Unfortunately, however, this wasn’t the only Trek adventure to cast doubt on female leadership.

The other woman captain depicted on Star Trek—the unnamed Romulan commander from “The Enterprise Incident”—performs more capably than Janice Lester but ultimately is undone by her feminine nature. With the Enterprise held at bay, and Kirk and Spock both captive on her Bird of Prey, the commander has a crowning achievement within her grasp. Yet she allows her infatuation with Spock to distract her and lets down her guard while trying to seduce the Vulcan in her cabin. While she’s slipping into something more comfortable, Captain Kirk slips away with her ship’s cloaking device. Her behavior could not be more dissimilar to that of the unnamed male Romulan commander from “Balance of Terror” whose life is ordered by duty and honor. She temporarily loses her grip on these responsibilities; Spock holds fast to his. “Why would you do this to me? What are you that you could do this?” the humiliated Romulan asks Spock. “First officer of the Enterprise,” the Vulcan replies. Outfoxed by the wily men of the Federation, she winds up a prisoner on the Enterprise.

The women of Sigma Draconis VI, from “Spock’s Brain,” use “pain bands” to lord over the males of their planet. But they’re a bunch of airheads who need Spock’s masculine brain to serve as the control matrix for the supercomputer that supports their bizarre, matriarchal-in-name-only civilization. Then there’s the Elasian leader Elaan (France Nuyen) from “Elaan of Troyius,” a petulant, uncouth, arrogant fire-eater whose impending marriage to a Troyian leader will avert a war between two rival planets. She’s a shrew who’s only fit to lead once she’s been tamed by Captain Kirk. In “The City on the Edge of Forever,” Kirk and Spock must prevent crusading missionary Edith Keeler from emerging as a prominent political figure. If Keeler survives, her growing influence will soften America’s masculinity, leaving the U.S. too timid and peace-loving, too stereotypically feminine, to effectively combat Nazi aggression. In these and other scenarios, Star Trek seemed unable to imagine a culture without the ingrained patriarchal attitudes of 1960s America.

Of Miniskirts and Mechanical Maidens

Even when Roddenberry placed women on the bridge of the Enterprise, he costumed them in miniskirts and go-go boots. The show’s female guest stars often wore far less. Star Trek’s so-called feminism was never allowed to interfere with costume designer Bill Theiss’s genius for cheesecake. After screening several episodes to familiarize himself with the show, Season Three producer Fred Freiberger reportedly remarked, “Oh, I get it. [It’s] tits in space.”

The show not only put female flesh on display, it allowed male characters to take in the view. Ogling women is an accepted pastime in the “liberated” world of Star Trek. Kirk and other male officers often turn their heads to check out a new female crewmate. Every man on board stares at Harry Mudd’s chemically enhanced mail-order brides in “Mudd’s Women.” Captain Pike and a colleague leer at Vena when she appears as an Orion slave girl in “The Menagerie.” And Kirk, McCoy, and Scotty gawk at an Argelian belly dancer in “Wolf in the Fold.” Even Spock exhibits this behavior in “The Cloud Minders,” gaping at the scantily clad Droxine (Dana Ewing). “Extreme feminine beauty is always disturbing,” he explains.

In other episodes, women are objectified in more literal ways. No fewer than four installments involve attempts by men to manufacture perfect mates. In “Mudd’s Women,” Harry Mudd (Roger C. Carmel) convinces three plain-looking old maids to take the forbidden “Venus drug,” which grants them unearthly beauty (and makes them acceptable brides). Once transformed, however, they become a commodity that Mudd sells to the highest bidder. That is Mudd’s bargain: to become marriage-worthy, the women must relinquish their humanity and become property. (This is moderated to an extent when, deprived of the Venus Drug, the women revert to their original looks and forge more adult and equitable relationships with their husbands/purchasers.) In “I, Mudd,” Mudd returns as the ruler of a planet populated entirely by gorgeous female androids of his own design. Both “What Are Little Girls Made Of?” and “Requiem for Methuselah” also involve powerful, intelligent men constructing idealized, robotic brides. These android dream women are beautiful, intelligent, and, perhaps most importantly, perfectly compliant. They are twenty-third-century Stepford Wives.

By far the most egregious misstep in Star Trek’s treatment of women comes at the conclusion of “The Enemy Within.” Earlier, the Evil Kirk attempted to rape Yeoman Rand. Now, during the show’s wrap-up on the bridge, Spock jokes with her about the experience. “The imposter had some … interesting qualities, wouldn’t you say, Yeoman?” he asks teasingly, apparently inferring that Rand secretly enjoyed the sexual assault. Somehow the line seems even more reprehensible coming from Spock, the show’s bastion of logic and intellect. It’s an exchange most fans would prefer to forget, but it remains emblematic of the show’s unfortunate tendency to treat women as expendable eye candy.

Dream Girls

Former Batgirl Yvonne Craig as the homicidal Orion temptress Marta, from “Whom Gods Destroy.”

Star Trek’s attitude toward women also can be observed through the romantic interests of the show’s main characters. Over the course of the original seventy-nine episodes, Kirk, Spock, McCoy, and Scotty all fell in love at least once, but these relationships were seldom equal partnerships. Most placed the man, for one reason or another, into a position of dominance over the woman. And these unions always ended by the close of the episode. None of the show’s female love interests became recurring characters (unless you count Nurse Chapel, whose feelings for Spock were unrequited). As Karen Blair writes in Meaning in Star Trek (1977), the first book to seriously analyze the appeal of the series, “In almost every episode we have a different female guest star, which usually guarantees that the character she portrays will be alien and disposable.”

Captain Kirk romanced dozens of women over the years but seemed to connect most strongly with Miramanee, the native woman he married and with whom he fathered a child while suffering from amnesia in “The Paradise Syndrome,” and Edith Keeler from “The City on the Edge of Forever,” for whom he’s tempted to sacrifice the future of humanity. Miramanee remains blatantly subservient to Kirk—she literally worships the “god” known as “Kirok.” The captain’s relationship with Edith takes place on more even footing, but Kirk secretly possesses centuries more knowledge (her dream of the future is his past), giving him a secret, mental upper hand and a comforting feeling of superiority.

When McCoy falls in love, it’s with Natrina (Katherine Woodville), high priestess of the Oracle from “For the World Is Hollow and I Have Touched the Sky.” While she displays exemplary moral fiber and leadership skills, Natrina remains only a few steps ahead of Miramanee in her primitive understanding of the world around her. McCoy submits to her religious leadership in order to become her mate but soon disobeys her because he knows what’s best for her people better than Natrina does.

Scotty, in “The Lights of Zetar,” falls for Lieutenant Mira Romaine (Jan Shutan), a brilliant scientist who is (at least) his intellectual equal. But she’s a young woman making her first deep space voyage and leans on the older, more seasoned Scotty for support and guidance. The engineer’s attitude toward Romaine is remarkably paternal—doting and protective.

Of all Star Trek’s romances, Spock’s relationships with Leila Kalomi (Jill Ireland) from “This Side of Paradise” and Zarabeth (Mariette Hartley) from “All Our Yesterdays” come the closest to being true partnerships between equals. But in both cases Spock is out of his mind, and he breaks off the relationship when he comes to his senses.

While it doesn’t involve a primary character, the “romance” between Zefram Cochrane (Glenn Corbett) and the gaslike, electromagnetic entity known as the Companion from “Metamorphosis” also proves illuminating. The superhuman Companion rescues Cochrane from a disintegrating spacecraft and nurses him to health. She protects and feeds him, restores him to youth and prevents him from aging, taking care of all his worldly needs for 150 years. When he complains of loneliness, the Companion immobilizes a shuttlecraft and pulls it to her tiny planetoid home, where Kirk, Spock, McCoy, and the critically ill Commissioner Nancy Hedford (Elinor Donahue) are to remain as distractions for Cochrane. Despite all the affection she has shown him during their century and a half together, Cochrane rejects the Companion once he realizes her interest in him is romantic. He’s only willing to embrace the Companion’s love once she forsakes her nearly limitless power and joins with the mortal form of Commissioner Hedford. To become acceptable to Cochrane, the Companion literally disempowers herself. Plus, Commissioner Hedford (who we learn has “never known love”) abandons her high-ranking career—in the middle of delicate negotiations to avert an interplanetary war, no less. Two powerful females essentially give up their jobs to get married, surrendering a galaxy full of possibilities to spend the rest of their lives on the outer space equivalent of a desert island as a housewife.

This seems to be the Star Trek feminine ideal. Certainly the relationship between Spock’s parents, Sarek (Mark Lenard) and Amanda (Jane Wyatt), follows this traditional pattern. Kang (Michael Ansara) and Mara (Susan Howard)—the husband-and-wife Klingon warriors from “The Day of the Dove”—have one of the show’s more enlightened relationships, but Mara serves under Kang’s command. On the other hand, women who challenge the masculine power structure—like Janice Lester from “Turnabout Intruder” or Marta, the mad, man-killing Orion woman from “Whom Gods Destroy”—are portrayed as villains and monsters.

If Star Trek often failed to live up to its stated ideals of equality, perhaps we shouldn’t judge Roddenberry and his writers too harshly. After all, in 1776, Thomas Jefferson wrote that “all men are created equal” and “endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights.” Yet when the Founding Fathers adopted the U.S. Constitution in 1787, they approved a government that kept millions of African Americans in slavery and denied women the right to vote. Sometimes these things take time.

Later Star Trek movies and series strived to correct the franchise’s troubling sexism. In 1986, Star Trek IV: The Voyage Home depicted (for the first time) a female Starfleet captain—the unnamed commander of the USS Saratoga, played by Madge Sinclair. Later, Kathryn Janeway (Kate Mulgrew) commanded the starship Voyager for seven seasons. And the prequel series Star Trek: Enterprise tried to retrofit female leadership into the Star Trek universe by introducing Captain Erika Hernandez (Ada Maris) of the pre-Federation Starfleet.

Just as importantly, the later series often presented strong female officers who exercised sound judgment and showed strong leadership skills. Without being defeminized like Number One, characters such as Lieutenant Tasha Yar (Denise Crosby) from The Next Generation, Chief Engineer B’Elanna Torres (Roxann Dawson) and Seven of Nine (Jeri Ryan) from Voyager, and Colonel Kira Nerys (Nana Visitor) from Deep Space Nine were capable of pulling their weight no matter what the situation demanded, up to and including a firefight or a donnybrook. Characters like these compensated in large measure for the deficits of the classic Trek series, moving Star Trek toward the future it talked about but at first seemed unable to visualize.