38

The Animated Adventures

Star Trek’s return to television didn’t begin with Gene Roddenberry. It started instead with Lou Scheimer, cofounder of Filmation Associates, which vied with Hanna-Barbera Productions and other animation studios in the mercurial, ultracompetitive Saturday morning cartoon market, where shows usually came and went quickly. In the early 1970s, Filmation was best known as the maker of Fat Albert and the Cosby Kids (1972–85), as well as numerous programs based on Archie Comics characters and DC Comics superheroes. Scheimer was always on the lookout for marketable properties with a built-in audience that might work in the half-hour animated format. And he was a Star Trek fan. So in 1972 Scheimer approached Trek creator-producer Roddenberry with the idea of reviving the series in cartoon form. Roddenberry was intrigued by Scheimer’s proposal but dreaded dealing with Paramount Pictures, with whom he shared ownership of the franchise. Predictably, Paramount tried to wrest control of the project away from Roddenberry, but the Great Bird refused, afraid that without his oversight the animated Star Trek would become “Archie and Jughead go to the moon.”

Unfinished Business

Ultimately Roddenberry was retained as Executive Consultant (and paid $2,500 per episode), with full creative control over the series, although he delegated day-to-day production chores to his trusted associate Dorothy Fontana, who served as the show’s story editor and associate producer. For Fontana, the animated series represented an opportunity to take care of unfinished business. “In 1969 when it [the live-action series] went off the air, we felt unfinished,” said Fontana in an interview for a documentary included with the Star Trek: The Animated Series DVD collection. “We hadn’t had a chance to complete the next voyages we had in mind, and this was one way to do it.” The show utilized the same “Bible” as the live-action series, and Roddenberry approved all scripts, sometimes adding touches of his own.

To bring the animated series as close to the original as possible, Scheimer and Fontana brought in most of the cast from the live-action Star Trek to supply the voices of their characters. Initially, they planned to save money by hiring only William Shatner, Leonard Nimoy, DeForest Kelley, James Doohan, and Majel Barrett Roddenberry, who would work with members of Filmation’s stable of voice artists. But Nimoy refused to participate unless Nichelle Nichols and George Takei voiced Uhura and Sulu. Doohan, Nichols, and Barrett Roddenberry wound up supplying voices for several other characters as well.

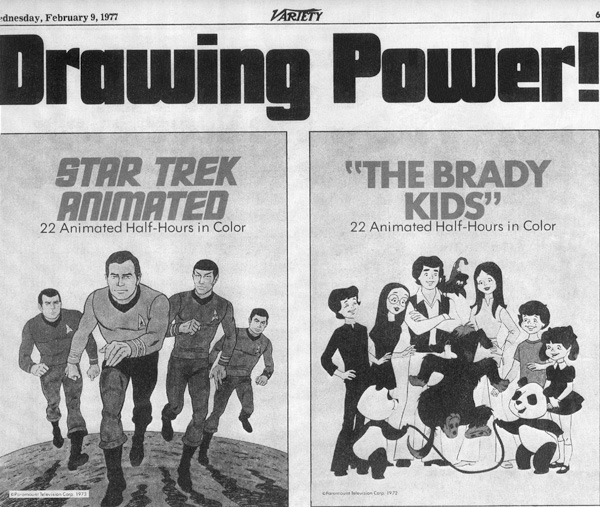

Close-up of a Variety ad designed to entice local stations to purchase syndicated reruns of the Star Trek animated series and another Filmation cartoon, The Brady Kids.

To further enhance the show’s Trek bona fides, Fontana secured the services of screenwriters who had worked on the live-action program. A 1973 Screen Writers Guild strike worked in her favor. The strike prevented guild members from working on live-action movies and TV shows, but cartoon shows were exempt. So Fontana was able to commission teleplays from Trek veterans David Gerrold, Margaret Armen, Samuel Peeples, and Stephen Kandel, and purchase scripts from Joyce Perry, Larry Brody, and Larry Niven, all of whom had submitted scenarios to Trek that were never produced due to the show’s cancellation. Walter Koenig, the only regular cast member left out of the animated show, also contributed a cartoon teleplay, as did Marc Daniels, who had directed more than a dozen episodes of the classic Trek series. Peeples, who wrote the second pilot for the live-action series (“Where No Man Has Gone Before”), wrote the first animated episode, “Beyond the Farthest Star.”

Hiring top talent wasn’t cheap, however. Star Trek became the most expensive Saturday morning cartoon on television, with production costs of $75,000 per episode. Since most of this money went to pay the cast, the writers, and Roddenberry, Star Trek didn’t look any more impressive than other Saturday morning cartoons. In terms of animation, it met the usual Filmation standard—far below that of, for example, a Walt Disney feature film but on par with the Hanna-Barbera product of the period.

But Is It Trek?

Despite Scheimer and Fontana’s painstaking and costly efforts to shore up the show’s credentials, however, the animated adventures’ status within the Trek universe remains a matter of passionate debate. In the late 1980s, Roddenberry disowned the cartoon series, officially “de-canonizing” it in 1988 and declaring that he never would have agreed to make the animated show if he had had any idea the franchise would later return to live-action TV and feature films. Nevertheless, many other Star Trek insiders, including Fontana, remain adamant that the animated show is canon-worthy, and several elements introduced through it were later “canonized” by their repetition in later live-action programs. Among other items, Captain James T. Kirk’s middle name—Tiberius—was first revealed in the animated installment “Bem” and later confirmed in the sixth feature film, The Undiscovered Country. And the holodeck, a concept utilized heavily by most of the later Star Trek series, first appeared in the animated adventure “The Practical Joker,” where it was referred to as the “recreation room.” Garfield and Judith Reeves-Stevens, fans of the cartoon show who served as writers and producers for Star Trek: Enterprise, intentionally used concepts from the animated series as often as possible to bring them into the canon.

For the most part, the animated show explored themes, ideas, and character relationships established by its live-action predecessor. But the cartoon introduced new elements as well. Freed from the production limitations of a live-action show, the Enterprise crew visited many more alien planets and encountered many more nonhumanoid species. These included two new members of the bridge crew, navigator Arax (voiced by Doohan), a three-armed, three-legged Edosian, and M’Ress (voiced by Barrett), a member of the catlike Caitian species, who served as the ship’s backup communications officer. Stories were limited only by screenwriters’ imaginations and the show’s half-hour, kid-friendly format.

Outstanding Episodes

“Yesteryear”—The most celebrated episode of the series was its second installment, “Yesteryear,” written by Fontana. Mr. Spock and Captain Kirk have been conducting time-travel experiments using the Guardian of Forever (the trapezoidal gateway used to transport Kirk and Spock into the past during the classic live-action episode “The City on the Edge of Forever”). When the duo returns to the Enterprise, Spock finds that no one other than the captain recognizes him; in his place, the ship employs an Andorian first officer. Somehow, he and Kirk have altered the timeline, resulting in Spock’s death at age seven while undergoing the Vulcan ritual known as the Kahs-wan, in which children validate their maturity by fending for themselves alone in the desert. Spock uses the Guardian to travel into the past and save his own life. In so doing, he meets not only his younger self but also a younger version of his father, Sarek (voiced by Mark Lenard).

Several elements of Fontana’s “Yesteryear” scenario were later accepted as canon, including the Vulcan rite of Kahs-wan and city of Shikahr (both of which were later discussed or depicted on Star Trek: Enterprise). “Yesteryear” also showed Spock’s pet sehlat, a saber-toothed, doglike animal first mentioned in the live-action “Journey to Babel.” His sehlat, I-Chaya, is mortally wounded during the adventure, which plays like a Vulcan variation on the theme of Old Yeller. Director J. J. Abrams revived the idea of Spock traveling in time to meet a younger version of himself for his 2009 feature film Star Trek. Producers submitted this episode to the National Academy of Television Arts and Sciences for consideration in the category of Outstanding Entertainment Children’s Series at the First Annual Daytime Emmy Awards. It earned a nomination but failed to win.

“The Lorelei Signal”—Written by Margaret Armen, who had penned three live-action episodes, “The Lorelei Signal” stands out as more boldly feminist than any episode of the classic Trek series. When the Enterprise responds to an interplanetary distress call, the all-male landing party (including Captain Kirk, Mr. Spock, Dr. McCoy, and Engineer Scott) beams down to Taurus II and falls under the hypnotic spell of the planet’s residents, a race of curvaceous blondes who turn out to be psychokinetic energy vampires. Lieutenant Uhura is forced to take over command of the ship. Joined by Nurse Chapel and an all-female away team, Uhura beams down to the planet, stuns the alien temptresses, and rescues the men, who are now near death. For obvious reasons, this remains Nichelle Nichols’s favorite animated episode. While the gender politics of the Star Trek have been hotly debated over the years (see Chapter 36, “What Are Little Girls Made Of?”), this episode’s feminism is beyond question. It’s significant that even the emotionless (but still male) Spock falls prey to the Taurian temptresses and that Uhura’s command skills and Chapel’s medical know-how ultimately save the day. The “Lorelei” title refers to a Germanic legend similar to the Greek myth of the siren, about beautiful maidens whose singing lures ships to their destruction. Armen also wrote “The Gamesters of Triskelion,” “The Cloud Minders” and “The Paradise Syndrome” for the live-action series, as well as “The Ambergris Element,” a far less remarkable animated yarn.

“More Tribbles, More Troubles”—While escorting two robot ships full of grain to a colony facing starvation, Kirk saves the pilot of a federation vessel under attack by a Klingon Bird of Prey. Then he discovers that the ship’s pilot is troublemaking tribble peddler Cyrano Jones, and his pursuer is Captain Koloth, Kirk’s antagonist from “The Trouble with Tribbles.” Jones is once again selling tribbles—new, genetically engineered tribbles that no longer multiply. However, the creatures still eat gluttonously and now grow huge, creating an entirely different set of headaches. Meanwhile, the Klingons maintain that Jones must be turned over to them, launching a series of attacks that threaten the Enterprise’s humanitarian mission.

A sequel to one of the most enduringly popular of all Star Trek episodes, “More Tribbles” remains highly amusing but isn’t as sharp as the original, in part because it tries too hard to mirror its predecessor, right down to a closing pun by Scotty (“If we’ve got to have tribbles, it’s best if all our tribbles are little ones”). Also, the animated series’ half-hour format made it tougher to develop the same careful balance of humor and political tension found in the sixty-minute live-action original. In fact, “More Tribbles” was originally written for Season Three of the live-action series. David Gerrold, who wrote the original “Trouble with Tribbles,” created “More Tribbles” at the request of Gene Roddenberry only to have the story rejected by producer Fred Freiberger, who replaced Roddenberry as line producer during the show’s final season and who never liked “The Trouble with Tribbles.” Gerrold’s live-action concept introduced ferocious, tribble-eating predators that bred as rapidly as the tribbles themselves; out of control, these creatures began feeding on Enterprise crew members. This plot was too violent for a Saturday morning cartoon, so Gerrold undertook a nearly complete overhaul. “More Tribbles” is bolstered by the return of actor Stanley Adams, who reprises his role as Cyrano Jones. William Campbell was approached to voice Koloth but was unavailable. Gerrold wrote one more animated episode, the seriocomic “Bem,” which is remembered primarily as the show that revealed Captain Kirk’s middle name.

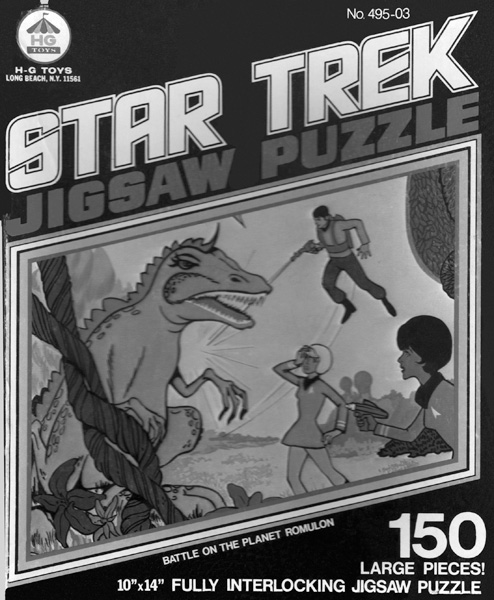

This mid-1970s jigsaw puzzle featured imagery from the animated series. Note the prominence of female crew members and Spock in his flight belt, seen only in the cartoon show.

“Mudd’s Passion”—The funniest—and one of the best—of the animated adventures, “Mudd’s Passion” reunites Kirk with another vexing adversary, Harry Mudd. This time, Kirk apprehends the interstellar shyster for selling an illegal drug—a love potion. Once aboard the Enterprise, however, Mudd tempts Nurse Chapel into using the drug on Mr. Spock. When (to Mudd’s surprise) the stuff works, Mudd creates havoc by using it on the rest of the crew and escapes in the confusion, taking Chapel as a hostage. Written by Stephen Kandel (who penned “Mudd’s Women” and “I, Mudd”), the “Mudd’s Passion” teleplay is razor-sharp, full of humorous dialogue and rich in character development. Kandel plays on well-established crew relationships, especially Chapel’s unrequited affection for Spock, in ways that are funny yet seem authentic. Roger C. Carmel returns to provide the voice of Harry Mudd and delivers a splendid performance. The show’s regulars also contribute spirited work. Nimoy and Shatner are hilarious playing the inexplicably lovelorn Vulcan and his puzzled commander. And, as the potion begins to affect the rest of the crew, each of the other principals enjoys a moment of hilarity. “I’ve saved just about everybody on this here ship,” DeForest Kelley coos as Dr. McCoy romances a young female lieutenant. “If the Enterprise had a heart, I’d save her, too. Now, let’s talk about your heart, my dear.”

“The Survivor”—While patrolling on the edge of the Romulan Neutral Zone, the Enterprise rescues a small spacecraft from a meteor storm. The pilot proves to be (or at least seems to be) Carter Winston, a renowned philanthropist long believed dead. Coincidentally, Winston’s former fiancée, Anne, now serves on Captain Kirk’s ship. Anne begins to suspect something is amiss when Winston rebuffs her. Eventually it’s revealed that the pilot is not Winston but a shape-shifting Vendorian who absorbed the consciousness of the dying philanthropist. The Vendorian is in league with the Romulans and leads the Enterprise into a deadly trap. But because he has absorbed so many of Winston’s memories, the shape-shifter also loves Anne, and to protect her, he double-crosses the Romulans and helps the humans escape. Written by James Schemerer, “The Survivor” boasts a compelling plot, similar in some aspects to the live-action episode “Metamorphosis,” and excellent dialogue, including some barbed repartee between Spock and McCoy, including this closing exchange:

McCoy: “I’m glad to see him [the Vendorian] under guard, Jim. If he’d turned into a second Spock, it would’ve been too much to take.”

Spock: “Perhaps. But then two Dr. McCoys just might bring the level of medical efficiency on this ship up to acceptable levels.”

Ted Knight, who would gain fame playing a dim-witted sportscaster on The Mary Tyler Moore Show, provides the voice of the Vendorian. “The Survivor” is also notable as the only Star Trek episode to mention McCoy’s daughter, JoAnna, a character created for, but then written out of, the live-action story “The Way to Eden.”

“The Slaver Weapon”—Perhaps the most imaginative episode of the animated series, “The Slaver Weapon” remains remarkable for several reasons. Written by Hugo and Nebula Award–winning author Larry Niven (best known for his Ringworld novels), this story introduces elements from Niven’s “Known Space” series into the Star Trek universe, including the warlike, telepathic Kzinti species. The episode also features several other novelties: It was the only Star Trek adventure since “The Cage” not to include Captain Kirk (only Spock, Uhura, and Sulu are featured); it’s the only animated story not to take place at least in part aboard the Enterprise; and it’s the only animated episode in which a character is killed. A three-member away team led by Mr. Spock is transporting an ancient “stasis box” to the Enterprise. These boxes—remnants from an ancient civilization known as The Slavers that once dominated the galaxy—often contain rare artifacts or fantastically advanced technology. Spock, Uhura, and Sulu are transporting it back to the Enterprise for investigation when they are duped and captured by the Kzinti, who open the box and discover a weapon of almost limitless power. Spock and friends must recover the weapon before the Kzinti use it to embark on a war against the Federation. “The Slaver Weapon” was adapted from Niven’s novella “The Soft Weapon.” Apparently Niven was happy with the episode itself but displeased when—like all the other animated episodes—it was novelized by Alan Dean Foster for publication in the Star Trek Logs book series. “So I wound up competing with myself, and I find that annoying,” Niven explained in a posting on his website.

“The Counter-Clock Incident”—The final animated installment produced, “The Counter-Clock Incident” introduces elderly Commodore Robert April, the “first captain of the Enterprise.” While transporting April to a retirement gala on the planet Babel, the Enterprise attempts to rescue another ship and is accidentally drawn through the heart of a supernova and into a negative universe, where time runs backwards. Everyone aboard the ship begins to regress in age, leaving April and his wife (the ship’s former chief medical officer) to save their beloved Enterprise a final time, as they temporarily return to youth and vitality. This highly enjoyable episode, written by John Culver (under the pseudonym Fred Bronson), builds on elements of Trek history and mythology: Robert April was the name Roddenberry gave the captain of his starship (then called the USS Yorktown) in his initial prospectus for Star Trek; the negative universe was introduced in the live-action episode “The Alternative Factor”; and the basic scenario (with the crew reverting in age) inverts the plot of the classic Trek adventure “The Deadly Years,” in which the crew ages rapidly. Also, it’s undeniably cute to see pint-sized versions of Kirk, Spock, and friends crawling around the bridge.

Other memorable animated adventures include:

• “The Time Trap,” which featured the Klingon Kor (introduced in “Errand of Mercy”) as well as cameos by members of several recognizable alien species from the live-action series (a Vulcan, an Orion, an Andorian, a Tellarite, and a Gorn), along with several species first seen on the animated show, including a Kzinti.

• “Once Upon a Planet,” a sequel to the live-action episode “Shore Leave.”

• “The Infinite Vulcan,” written by Walter Koenig, an imaginative but convoluted scenario that integrates the Eugenics Wars backstory from “Space Seed” and “The Conscience of the King.”

• “How Sharper Than a Serpent’s Tooth,” despite a shopworn storyline (a thinly veiled rewrite of “Who Mourns for Adonais?”), won Outstanding Entertainment Children’s Series at the Second Annual Daytime Emmy Awards, bringing Star Trek its first Emmy win in eighteen nominations (including sixteen, in various categories, for the live-action show and the animated series’ previous nomination a season earlier in the same category). “How Sharper Than a Serpent’s Tooth”—in which the Enterprise encounters Kukulkan, a spacefaring feathered serpent who visited Earth centuries ago and was mistaken for a god by the ancient Mayans—was also the first Trek episode to feature a Native American Starfleet officer, Ensign Walking Bear, a Comanche.

• “Keep America Beautiful” PSA—Filmation also produced a public service announcement for the nonprofit Keep America Beautiful Inc., in which the Enterprise encounters the “Rhombian Pollution Belt.” Set on the bridge, the spot features Captain Kirk, Mr. Spock and Lieutenant Sulu voiced by Shatner, Nimoy, and Takei. Arax and Uhura are also shown but have no lines. For reasons unknown, this charming spot was not included with the DVD release of the animated series.

Although today it tends to polarize fans (for many, it’s a love it or hate proposition), in its day the animated series offered new stories (albeit sometimes juvenile ones) to a fan base starved for new Star Trek adventures after watching the same seventy-nine episodes over and over again in syndication. In an era when few Saturday morning cartoon series lasted more than a single season, Star Trek earned a renewal, running on NBC at 10:30 a.m. EST in 1973 and 11:30 a.m. EST in 1974. Sixteen episodes were produced for the first season and another half-dozen for Season Two. While it garnered solid ratings, Star Trek failed to attract the young viewers essential to long-term Saturday morning success. “We ended up doing a show that was basically the same as the nighttime show—same writers in many cases, same actors obviously and the same audience, too,” Hal Sutherland, who directed most of the animated episodes, said in a DVD interview. “The problem was, the audience was all in their 20s and 30s, and our [Filmation’s] normal audience was, like, 8 to 10.”

As a result, NBC once again cancelled Star Trek, this time after only two seasons. Yet, like its live-action predecessor, the animated series went on to a long and prosperous afterlife in syndication.