40

Vintage Star Trek Merchandising

In 1977, 20th Century-Fox unleashed a blockbuster of previously unimaginable proportions in George Lucas’s Star Wars, which not only shattered all existing box-office records but also generated hundreds of millions of dollars in ancillary revenue through the sale of toys, T-shirts, posters, soundtrack albums, and other ephemera. Immediately, rival studios began a frantic search for properties with similar merchandising possibilities. Paramount quickly realized that in Star Trek it already had one. For years, diehard fans had supported Trek not only by watching the show but by spending their money. They had turned an assumed-dead TV series into a merchandising bonanza, snapping up Trek-branded toys, model kits, books, trading cards, T-shirts, buttons, posters, bumper stickers, watches, and … well, just about everything else in the galaxy. Fans’ passion for all things Trek played a major role in convincing Paramount Pictures to revive the franchise with a theatrical film.

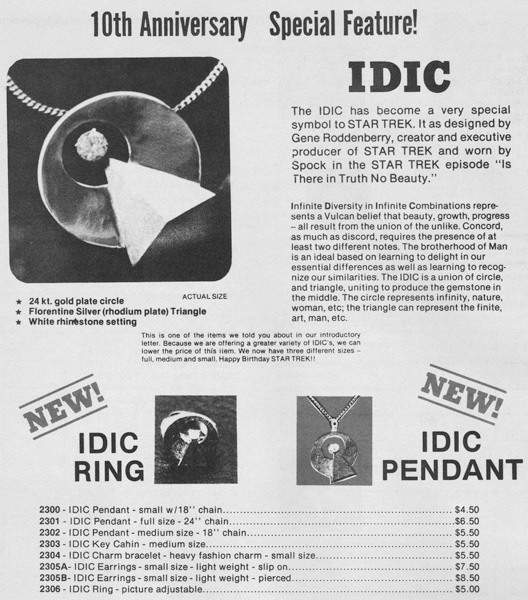

Lincoln Enterprises

Well into the 1970s, Roddenberry continued to sell IDIC jewelry through his Lincoln Enterprises mail-order business. (This ad ran in a 1978 catalog.)

From the beginning, creator-producer Gene Roddenberry grasped the merchandising potential of Star Trek, and in 1967, he set up a mail-order company, Lincoln Enterprises, to capitalize on it. The business was actually owned by Roddenberry’s attorney, Leonard Maizlish, who officially turned the company over to Majel Barrett Roddenberry in the early 1980s. Operated by Roddenberry and Barrett, Lincoln began as a mechanism for handling the show’s copious fan mail and requests for photographs and other souvenirs. Soon it was selling publicity photos and copies of scripts through mail-order catalogs and at science fiction conventions. Initially, in apparent violation of Writers Guild of America rules, the authors of the teleplays received no compensation from these sales, but Lincoln ironed out a deal with the Guild to continue selling scripts.

Beginning in 1968, Lincoln offered fans the chance to own a piece of their favorite show—literally—when the company began selling 35 mm frames clipped from the program’s daily outtakes. This development stoked brewing animosity between Paramount Pictures and Roddenberry, since technically this footage was owned by the studio and not the producer. Also in 1968, another Lincoln endeavor damaged the already strained relationship between Roddenberry and Leonard Nimoy. During production of the episode “Is There in Truth No Beauty?,” Roddenberry inserted a scene in which Kirk and Spock explain to guest star Diana Muldaur the significance of a stylized medal the Vulcan is wearing—the IDIC, short for “infinite diversity in infinite combinations.” This interlude served no function within the framework of the plot; it was created specifically to introduce IDIC pins and medallions, which were about to go on sale from Lincoln Enterprises. Nimoy felt that this ploy cheapened the show and protested vociferously. The sequence was rewritten to minimize the dialogue about the IDIC (which Kirk refers to as “the most revered of all Vulcan symbols”), and Nimoy reluctantly played the scene. In the finished episode, Spock models both an IDIC brooch (which receives a loving close-up) and, later, a large IDIC necklace.

By the late 1970s, Lincoln had grown into a thriving cottage industry, selling T-shirts, patches, iron-on transfers, buttons, bumper stickers, posters, stationary, commemorative coins, and jewelry (including IDICs), as well as 35 mm frames, teleplays, and reprints of the series’ writer’s guide. Roddenberry also used Lincoln to promote his post-Trek productions, selling copies of his scripts for Pretty Maids All in a Row, Genesis II, Planet Earth, The Questor Tapes, Spectre, and even his unrealized Tarzan and Magna I projects. The company remains in business, now operated by Rod Roddenberry, whose Roddenberry.com website replaced the old mail-order catalogs.

AMT Model Kits

AMT’s “U.F.O. Mystery Ship” (originally released as the “Leif Ericson Galaxy Cruiser”) featured a spacecraft designed by Matt Jefferies for Star Trek but never used on the series. (This is one of Round2’s reissue kits, struck from the original AMT molds and reproducing the original packaging.)

Among the earliest and most popular Trek tie-ins were plastic model kits manufactured by Troy, Michigan–based AMT, then a leading producer of model cars and trucks. In 1966, during the show’s first season, Roddenberry struck a deal with AMT: The company’s skilled model makers helped production designer Matt Jefferies create some of the miniatures used in the show’s production; in exchange, AMT received an exclusive license to produce and market Star Trek model kits. AMT craftsmen also constructed the life-size mock-up of the shuttlecraft Galileo 7. A plastic reproduction of the USS Enterprise, which first appeared in 1966, marked AMT’s first venture beyond automotive models. The Enterprise became a top seller and was followed a year later by a Klingon battle cruiser kit. During the show’s cash-strapped third season, Jefferies sometimes used AMT models in the background for complex shots involving multiple spacecraft. These models are recognizable by their lack of internal lights.

Eventually, AMT issued several more Star Trek kits: a Romulan Bird of Prey; the Galileo 7 shuttlecraft; the Enterprise bridge; Space Station K-7 (from “The Trouble with Tribbles”); and an “Exploration Set” including ¾-scale replicas of a phaser, communicator, and tricorder. The model series outlived the television show, continuing well into the 1970s. AMT (short for Aluminum Model Toys) leased the international Star Trek model rights to rival Aurora, a company best known for its figure model kits. In 1976, Aurora introduced a model of Spock, depicted with phaser drawn against what looked like a three-headed space serpent. Through a reciprocal agreement, the Spock model was sold by AMT in the U.S.

AMT went on to release a plethora of models based on other sci-fi properties, including Star Wars, Alien, and Space: 1999, as well as kits featuring spacecraft from the Star Trek feature films, The Next Generation and Deep Space Nine. In 1968, AMT issued a model spaceship designed by Jefferies for Star Trek but never actually used on the series—an angular, double-finned craft sold as “The Leif Ericson Galaxy Cruiser.” This kit included a 45 rpm record of “the sounds of outer space” and a two-page short story (“Danger on an Alien Planet”) depicting the adventures of the ship’s crew, led by the valiant Captain Walker of the Galactic Expeditionary Force. The Leif Ericson’s Star Trek origins were never mentioned. In the 1970s, the Leif Ericson was recast in glow-in-the-dark plastic and sold as the “Interplanetary UFO Mystery Ship.”

AMT was absorbed by Britain’s Lesney Products, makers of the Matchbox line of toy cars, in 1978. Ownership of the brand changed hands twice more, winding up with Round 2 LLC, a South Bend, Indiana–based model maker known for reissues of classic models, in 2007. Beginning in the late 2000s, Round 2 began selling new pressings of the classic AMT Star Trek models cast from the original molds. Vintage AMT model kits remain treasured collectibles. AMT’s original, exclusive Trek license expired in 1999, and since then several other companies—including Revell-Monogram, Polar Lights, and Bandai—have also released Star Trek models. In addition, many unlicensed, homemade, or semiprofessional “garage kits” have emerged over the years. These models—from makers with names like Warp Models, Federation Models, and Nova Hobbies—often feature lesser known vessels of interest only to hardcore fans, such as the Botany Bay from “Space Seed.”

Trading Cards

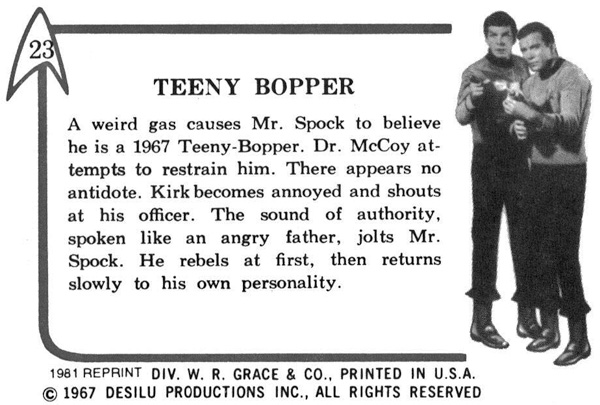

Front and back of one of the most bizarre (and hilarious) of the 1967 Leaf trading cards, which were quickly withdrawn from circulation. (This image derives from a 1981 reprint edition.)

Chicago-based Leaf Brands (now known as Donruss) issued the first set of Star Trek trading cards in 1967. These cards, which were not distributed outside the Midwest, were sold briefly but quickly recalled. This may have been due to a licensing issue or because Roddenberry was displeased with the product, which was far from ideal. The Leaf cards featured grainy black-and-white photos backed by poorly written text that misidentified the picture on the front and “recapped” absurd stories never featured on the show. Card Number 63, for instance, features a publicity still of Spock from “The Cage” but suggests that this shot originates from an episode where the Enterprise is “demobilized” and boarded by space pirates. Card 23 backs a picture of McCoy supporting a dazed Spock with this far-fetched explanation: “A weird gas causes Mr. Spock to believe he is a 1967 teeny-bopper. Dr. McCoy attempts to restrain him.” And Card 45 recounts a nonexistent episode where Spock (“again the dead center target of an enemy ion fuser”) escapes the unnamed enemy by telling jokes (“Why do some men wear suspenders?”). Despite—or perhaps because of—these oddities, the ultra-rare Leaf Star Trek cards, which originally sold for a nickel per pack, now command a princely $35 or more per card. In pristine condition, a complete set of seventy-two cards can sell for thousands. Even empty wrappers are valuable. An unauthorized reprint series of these cards emerged in 1981.

The next set of Star Trek trading cards, from a British maker called A&BC, featured sharp-looking color photos but had other drawbacks. Most importantly, all fifty-five cards in the series originated from a single episode—“What Are Little Girls Made Of?” And once again the text on the back of the cards contained glaring inaccuracies. Among other errors, Spock is identified as “part Martian.” These cards were sold only in the U.K. The first set of Star Trek trading cards widely available in the U.S. was issued by industry giant Topps in 1976. Although best known for originating the modern baseball card in 1952 (and monopolizing that market for nearly thirty years), Topps was also a pioneer of nonsports trading cards, issuing sets devoted to the space program, the life story of President John F. Kennedy, and the Beatles. In 1962, Topps released its now-legendary (and ultracollectible) Mars Attacks cards. The company’s 1976 Star Trek cards, which sold for ten cents per pack, included eighty-eight cards and twenty-two stickers with color frame enlargements from various episodes on the front and accurate descriptions (in “Captain’s Log” format) on the back. In the years since, numerous companies, including Skybox and Rittenhouse Archives, have issued additional trading card series devoted to the Star Trek franchise. In 1997, Skybox inserted autographed cards (one signed card per box) into random packs of its Star Trek: The Original Series - Season One cards. This gambit was quickly copied by other companies and has become nearly a standard practice for cards based on movies or television shows.

Mego Action Figures

Mego was a leading manufacturer of action figures in the 1970s, marketing eight-inch poseable dolls with cloth uniforms and plastic accessories based on Marvel and DC Comics superheroes, as well as film and television properties including Planet of the Apes, The Wizard of Oz, and Universal Studios monsters. Mego also issued figures in the likenesses of musicians and celebrities such as Farrah Fawcett, Sonny and Cher, and Kiss. The secret to the company’s success was the ingenious design of its plastic figures, which had interchangeable heads. This enabled the company to stockpile standard body types that, by changing only the costume and the head, could be refitted to resemble many different characters.

In 1974, the company issued its first collection of Star Trek figures, which included Kirk, Spock, McCoy, Uhura, Scotty, and a generic Klingon (who favored William Campbell’s Koloth from “The Trouble with Tribbles”). Not surprisingly, Mego’s Star Trek toys sold like crazy. The company followed with two waves of Star Trek Aliens figures, released in 1975 and ’76. These eight dolls varied widely in their fidelity to the characters seen on the show. Mego’s Romulan, Andorian, and Cheron were quite faithful, but its Talosian, Gorn, and Mugato looked almost nothing like their on-screen counterparts. And one figure—“The Neptunian,” a bipedal lizard with an insectoid head—was a wholly original creation with no origin in Star Trek at all. Mego’s Star Trek line also included a series of “playsets,” including the Enterprise bridge (complete with a plastic replica of the captain’s chair); a transporter room (featuring a spinning “transporter” that made figures seem to disappear); and a pair of “communicator” walkie-talkies. Mego thrived throughout the early and middle 1970s, but its sales declined late in the decade after rival Kenner outbid Mego for the license to produce Star Wars action figures. Mego went out of business in 1983.

Although many far more realistic Star Trek action figures have been sold in the decades since, the original Mego toys retain a nostalgic value for many fans. Some of them also carry a big-dollar collectible value. Over the years, hobbyists recreated the classic Mego Trek figures and expanded the line with “custom” versions of characters like Nurse Chapel and Harry Mudd, with homemade heads and hand-sewn uniforms. Beginning in 2006, EMCE Toys, in conjunction with Diamond Select Toys, began releasing authorized recreations of the original Mego Trek figures as well as a newly created Khan figure. Nine of the thirteen classic Mego figures have been reissued so far, and EMCE has announced plans for releases featuring Lieutenant Sulu and Ensign Chekov, whom Mego ignored, and a revised, accurate version of the Gorn.

Scores of other Trek products were also produced during this era. Puzzle and trivia books from various publishers, board games, and a Bally pinball machine served as the forerunners of the later, highly lucrative Star Trek video game franchise. Fans could also invest in Star Trek beach towels, bed linens, belt buckles, dinnerware, lunch boxes, Halloween costumes, paint-by-numbers kits, Frisbees, and freeze pops. In 1970, Primrose Confectionary even sold Star Trek–branded candy cigarettes.

About the only thing fans couldn’t buy were the shows themselves—at least not officially. Sony’s first Betamax home video systems went on sale in the spring of 1975, in the midst of Trek’s popular resurgence. The following year, JVC’s first Video Home System (VHS) recorders entered the market. While Paramount Pictures and other Hollywood Studios sat out the ensuing format war, Star Trek became one of the most-taped programs in the early history of the medium. Bootleggers soon began hawking unauthorized recordings of the program in both formats. Paramount Pictures Home Entertainment didn’t begin selling authorized, prerecorded VHS tapes until 1985. However, in 1979, RCA produced licensed editions of Star Trek episodes in its proprietary SelectaVision CED format (video discs played with a special needle, like a vinyl record album). In 1982, Pioneer released the series on laser disc.