41

The Long Voyage Back, 1975–79

In March 1978, Paramount Pictures held a massive press conference, with scores of journalists from around the world, to announce the return of Star Trek. Production would soon commence for Star Trek: The Motion Picture, a $15 million theatrical feature produced by Gene Roddenberry and directed by Oscar winner Robert Wise, which would reunite the entire cast of the TV series and introduce new characters as well.

Fans were elated, but most had one question: What took so long?

Although few outsiders knew it at the time, the revival of Star Trek was a torturously convoluted process that consumed much of the 1970s and left a barge-load of false starts and scuttled projects in its wake. As early as 1972, former story editor Dorothy Fontana revealed that Paramount (which essentially co-owned the franchise with Roddenberry) was considering a Star Trek feature film. The following year, a frustrated Roddenberry told reporters that NBC was interested in resurrecting the series but that Paramount refused to move forward because it feared new episodes would deflate the market for Trek’s highly profitable syndicated reruns. The Star Trek animated series premiered that fall, but this Saturday morning cartoon show did little to quell the pent-up demand for new live-action Trek adventures. Over the next five years, Roddenberry and a host of other writers, producers, and directors worked on a myriad of film and television efforts intended to resuscitate the franchise. Most of these led nowhere.

The God Thing (1975)

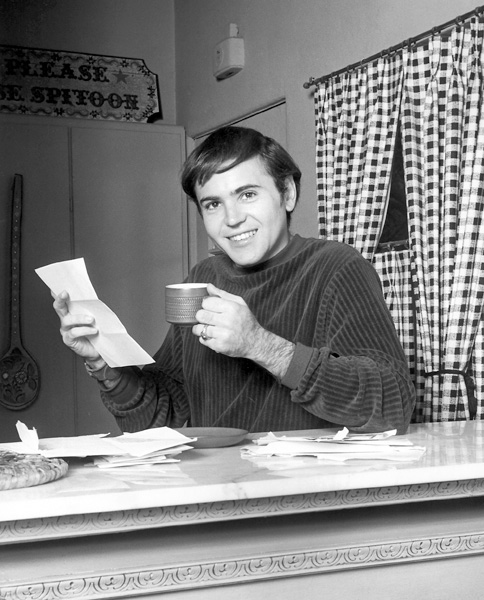

Walter Koenig, seen here reading his fan mail, later novelized Gene Roddenberry’s rejected God Thing screenplay.

Throughout the 1970s, Paramount leadership dithered and vacillated regarding Star Trek. The series’ success in syndication and merchandising was unprecedented, and executives didn’t know what to make of it. Some believed the show’s popularity was a fad that would quickly pass. With that possibility in mind, in 1975, the studio hired Roddenberry to develop the screenplay for a low-budget ($2–3 million) theatrical film. The idea was to rush the picture into production and capitalize on the Trek craze before its appeal faded. The studio even gave Roddenberry his old office back to write the screenplay. One day, William Shatner—who was on the lot filming his short-lived TV series Barbary Coast—found Roddenberry in the old Star Trek offices, pounding away on a typewriter. The actor recalls in his book Star Trek Movie Memories:

“Hey, Gene!” I called from the doorway. “Didn’t anybody tell you? We got cancelled!”

“Whaddya mean?” he said, not looking up but continuing to type. “I’m almost finished revising our 1968 scripts!”

In fact, the erstwhile Great Bird of the Galaxy was writing a screenplay titled The God Thing. Although the script itself has never been published, a basic outline of the story can be discerned by piecing together accounts from the published memoirs of Roddenberry, Shatner, Susan Sackett (Roddenberry’s secretary), and Water Koenig.

Admiral James T. Kirk hastily reassembles the crew of the starship Enterprise and races out to counter a giant alien Object, which has already destroyed the starship Potemkin and is now headed toward Earth. The Object claims to be God and demonstrates its powers by restoring the amputated legs of helmsman Sulu (injured in the earlier battle). A shape-shifting emissary from the Object boards the Enterprise, appearing in several forms including that of Jesus Christ. Eventually, the Object is revealed to be a malfunctioning interdimensional computer intelligence programmed to relate and interpret interstellar law. During its first visit to Earth, the Object was mistaken for God by the Hebrews of the Old Testament; Christ, it turns out, was one of its mechanical lawgivers. Finally, Kirk convinces the Object to return to its own dimension.

Paramount rejected this scenario as too anti-religious. “Gene had been iconoclastically asking, What if the God of the Old Testament, full of tirades and demands to be worshipped, actually turned out to be Lucifer?” Sackett wrote in The Making of Star Trek: The Motion Picture. “If so, was the serpent’s offer of the Fruit of Knowledge actually a gift from the real God? Captain Kirk versus God. This was not the story Paramount had expected!”

Despite the studio’s antipathy for this concept, Roddenberry remained fascinated by his God Thing story and incorporated many elements from it into the final, approved script for Star Trek: The Motion Picture. He also planned to novelize the rejected screenplay, but he never completed the manuscript. In 1976, Walter Koenig collaborated with Roddenberry on a novella-length adaptation of The God Thing, but the book was abandoned when Roddenberry received a green light for the TV series Star Trek: Phase II. In 1993, The God Thing (billed as a “lost Star Trek novel by Gene Roddenberry and Michael Jan Friedman”) was solicited by Pocket Books, but the title never appeared. Friedman, who had written several Star Trek novels, was assigned to expand and revise the Roddenberry-Koenig God Thing novella by Pocket Books editor David Stern, but the project was abandoned at the request of the Roddenberry estate.

The Billion Year Voyage and Other Tales from the Scrap Heap (1976)

The studio’s rejection of The God Thing dimmed the prospects for a quick cash-in on the Star Trek “fad,” but Paramount decided to give Roddenberry a second chance. He had until the spring of 1976 to develop a usable screenplay. Screenwriter Jon Povill, who worked extensively with Roddenberry during this period, produced a treatment in which Captain Kirk and friends travel into the past to battle a psychic cloud that is driving the people of the planet Vulcan mad. Roddenberry liked the idea but felt Povill’s story lacked the scope necessary to carry a feature.

Roddenberry then penned a time-travel yarn of his own. In this tale, a shuttlecraft crewed by Spock, Scotty, and a handful of other officers gets sucked into a black hole, triggering a reaction that temporarily scrambles the molecules of the Enterprise and its crew, who eventually coalesce back into existence after an eleven-year absence. But the universe as they knew it is gone. The shuttle was transported into the past (Earth, circa 1937), where Scotty’s well-intentioned efforts to avert World War II created a corrupted timeline. Now the Earth is ruled by a benevolent supercomputer. The planet is peaceful, famine and sickness have been wiped out, but human beings have become mere automatons with no ambition or imagination. After wrestling with the pros and cons of the situation—after all, Earth is a near-utopia, and millions of lives have been saved—Kirk decides to travel into the past and restore the original timeline. It’s up to the crew of the Enterprise to restart the Second World War! While the available details of this story remain sketchy, this seems to be a very promising scenario, reminiscent in key aspects of the treasured “City on the Edge of Forever.” Nevertheless, Paramount rejected this concept as well.

Still hoping to exploit Star Trek’s surging popularity, Paramount next turned to writers other than Roddenberry in its search for a filmable story. Executives, including Roddenberry, entertained pitches from four writers: John D. F. Black, who had served as story editor during the first half of Star Trek’s initial season and penned the key episode “The Naked Time”; Harlan Ellison, the author of “The City on the Edge of Forever”; and fellow esteemed science fiction authors Ray Bradbury and Robert Silverberg.

Black’s concept involved a black hole that was being used as an interstellar garbage dump by the inhabitants of a renegade solar system. After consuming centuries of space junk, the black hole explodes and begins consuming whole planets and suns. The Enterprise is sent to find some way of preventing the hole from devouring the entire galaxy. Paramount dismissed the idea because, as Black has often repeated in interviews, “it wasn’t big enough.”

Ellison proposed a story where the Enterprise crew travel into the past to combat a race of time-hopping alien reptiles bent on the conquest of Earth. The movie would have begun with a series of unexplained occurrences, including the disappearance of one of the Great Lakes. Then a mysterious, cloaked figure would have been seen kidnapping members of the Enterprise crew. The kidnapper would be revealed as Captain Kirk, rounding up his former crew for a secret mission back in time to combat the nefarious lizard people. According to numerous accounts of the meeting (including Ellison’s, from his book about the writing of “City on the Edge of Forever”), the author’s pitch came to an abrupt end when Paramount executive Barry Trabulus asked if the story could involve Mayans. Trabulus, intrigued by Erich von Daniken’s book Chariots of the Gods (which postulated that extraterrestrials may have influenced the development of ancient civilizations, including that of the Maya) wanted to shoehorn that concept into Ellison’s story. The testy Ellison dismissed Trabulus’s suggestion as “a stupid idea.” A confrontation resulted, and Ellison stormed out of the meeting.

Details of Bradbury’s idea remain elusive, but Silverberg pitched a story called The Billion Year Voyage that was more pure science fiction than the typical Trek sci-fi action yarn. In it, an Enterprise away team would have discovered the ruins of a long-dead but superadvanced civilization known as the Great Ones and battled other alien races for the Great Ones’ fantastically powerful relics. This scenario, which shares some common concepts with Larry Niven’s excellent animated Trek adventure “The Slaver Weapon,” was also rejected.

Planet of the Titans (1976–77)

Paramount’s nearly two-year search for an acceptable Star Trek story came to an end—or so it seemed—in October 1976 when the studio finally purchased a scenario titled Planet of the Titans from British screenwriters Chris Bryant and Allan Scott.

The Federation and the Klingon Empire both lay claim to a recently discovered planet that may be the home world of the near-mythical Titans, an ancient, long-extinct, superadvanced race. The possible treasures awaiting discovery on the planet could tip the balance of power in the galaxy, but the world is about to be consumed by a black hole. The Enterprise arrives and discovers a second opponent even more formidable than the Klingons—the mysterious Cygnans, who effected the disappearance of the Titans eons ago. In order to defeat the Cygnans, Kirk is forced to fly the Enterprise into the black hole, which catapults the starship through time and space to prehistoric Earth. There, Kirk and his crew aid the primitive humans of the era and suddenly realize that they themselves are the legendary Titans.

Curiously, this story plays like Silverberg’s discarded Billion Year Voyage mashed up with pieces and parts from many of the other rejected tales, plus a dash of Chariots of the Gods at the end. Story elements from The God Thing were also present—including an opening scene depicting the destruction of a Federation vessel (here named the Da Vinci) and Spock studying on Vulcan to purge the last vestiges of his humanity. Bryant and Scott’s yarn featured several spectacular action sequences, including the separation of the Enterprise’s saucer section from the rest of the ship during a battle with the Klingons.

Paramount assigned Planet of the Titans a budget of $7.5 million and hired writer-director Philip Kaufman, who would later helm such successful films as Invasion of the Body Snatchers (1978), The Right Stuff (1983), and The Unbearable Lightness of Being (1988), to oversee the production. To devise the look of the picture, the studio engaged production designer Ken Adam, renowned for his work on the James Bond films and Stanley Kubrick’s Dr. Strangelove, along with conceptual artist Ralph McQuarrie, who had served a similar function on George Lucas’s Star Wars and Steven Spielberg’s Close Encounters of the Third Kind. Planet of the Titans was scheduled to shoot in England beginning in late 1977.

Bryant and Scott expanded their treatment into a full screenplay, which they delivered in March 1977. Kaufman, a gifted writer who penned (among other things) the story for Spielberg’s Raiders of the Lost Ark (1981), immediately began revising the script. His version more prominently featured Spock and a Klingon commander he hoped would be played by Japanese screen legend Toshiro Mifune. But Kaufman clashed with Roddenberry, who felt the director’s alterations were turning the movie into something that wasn’t Star Trek. Paramount chief Barry Diller shared Roddenberry’s trepidation about the script and was alarmed by the production’s rising costs. By this point the budget had ballooned to $10 million, and shooting was still months away. In early May, before Kaufman had completed his rewrite, Diller abruptly cancelled Planet of the Titans.

Just a few weeks later, Star Wars premiered.

Star Trek: Phase II (1977)

Diller, who had taken over as CEO of Paramount in 1974 and moved up to chairman in 1976, had an ulterior motive for shutting down Planet of the Titans. He dreamed of starting a fourth television network and saw Star Trek as the anchor for this venture, a highly desirable property with a young, relatively affluent built-in audience. The original Trek series was being broadcast on 137 stations across the U.S. at the time. Diller’s plan, announced on June 10 (about a month after Planet of the Titans was scrapped), was for the new Paramount network to begin modestly, with one night of programming per week: Star Trek: Phase II, an all-new weekly series, at 8 p.m. Saturdays, followed by a made-for-TV movie at 9. (Diller, as a programming VP at ABC in the 1960s, had pioneered the weekly telefilm concept with that network’s long-running ABC Movie of the Week.) The Paramount network was slated to debut in February 1978.

Roddenberry promptly corralled Paramount executive Robert Goodwin to serve as line producer for Phase II, brought in screenwriter Harold Livingston to serve as coproducer/story editor, and tried to hire his old friend Matt Jefferies away from the hit series Little House on the Prairie to return as production designer. Jefferies demurred but recommended Joe Jennings, who Roddenberry hired as art director. Roddenberry also brought back Trek veteran William Ware Theiss to design costumes for the new show.

Most of the original cast was soon brought on board as well. The glaring exception was Leonard Nimoy, who was embroiled in a lawsuit against Paramount over royalties from the sale of merchandise featuring his (Spock’s) likeness. He had also filed a Screen Actors Guild complaint against Roddenberry due to the producer’s unauthorized use of the Star Trek blooper reel at speaking engagements. Although Roddenberry hoped to woo Nimoy into making guest appearances on Phase II, the producer hired actor David Gautreaux to portray Xon, the Enterprise’s new, young, full-Vulcan science officer. (Spock would be off teaching at the Vulcan Science Academy.) Roddenberry also planned to introduce two new characters: Commander Will Decker (the son of Commodore Matt Decker from “The Doomsday Machine”), envisioned as a younger version of Kirk who would serve as the ship’s second-in-command; and Ilia, an exotically beautiful, bald female Deltan, a telepathic species known for its brazen sexuality.

Planet of the Titans’ $10 million-plus budget made the project impractical for television, sending Roddenberry back to the drawing board in search of a screenplay for the Star Trek: Phase II pilot telefilm. He dusted off “Robot’s Return,” an episode concept from his failed Genesis II TV series that was highly reminiscent of both his previously jettisoned God Thing screenplay and John Meredith Lucas’s classic Trek episode “The Changeling.” He handed off the story outline and other materials to Alan Dean Foster, a best-selling science fiction author who had novelized the teleplays of the Star Trek animated series. Foster cooked up an expanded version of the story titled “In Thy Image,” which was quickly selected to serve as Phase II’s feature-length pilot episode. The concept was favored by both Roddenberry and Michael Eisner, who had succeeded Diller as Paramount CEO. Livingston expanded the yarn into a full-length teleplay.

Roddenberry, hoping to avert the teleplay gap that plagued the original Star Trek during its first season, solicited additional stories from many different writers. A few of these were later developed into treatments or even full-length scripts. Foster submitted a story where the Enterprise discovers a parallel Earth akin to the American South of the early 1800s, only with whites enslaved by blacks. Shimon Wincelberg, John Meredith Lucas, and Margaret Armen, all of whom wrote for the original Star Trek, sold stories to Phase II. Roddenberry bought a half-dozen scenarios from sci-fi author Jerome Bixby, who had written four classic episodes including “Mirror, Mirror” and “Day of the Dove.” In all, eighteen scenarios were purchased, including:

• “The Child” by Jon Povill and Jaron Summers, in which Ilia is impregnated by a noncorporeal alien life force. This scenario was later revived for The Next Generation.

• “To Attain the All” by Norman Spinrad (who had penned “The Doomsday Machine”), about a superadvanced, noncorporeal alien race who offers the gift of immortality and other wonders in exchange for the temporary use of human bodies to move about the galaxy. Although similar to the Season Two episode “Return to Tomorrow,” Spinrad’s story took a very different direction, with the aliens remaining benevolent but their gifts proving too dangerous.

• “The Prisoner” by James Menzies, in which someone who looks like Albert Einstein claims to have been abducted by aliens during the twentieth century and kept prisoner on a distant planet.

• “Tomorrow and the Stars” by Larry Alexander, in which a transporter accident sends Kirk back in time to Pearl Harbor just prior to the 1941 Japanese attack

• And “Devil’s Due” by William Lansford, designed as a science fiction update of “The Devil and Daniel Webster,” with Kirk in the role of the defense attorney.

Within a few months, Paramount’s plans for a fourth television network fell apart. The studio couldn’t prebook enough advertising to make the operation profitable. Despite this setback, Diller retained his dream of founding a fourth network and realized that goal after jumping from Paramount to Fox in 1984. Along with owner Rupert Murdoch, Diller launched the Fox Broadcasting Company in 1986. Nine years later, Paramount belatedly premiered its UPN Network, which lasted until 2006, when it merged with the Warner’s failed WB Network to form the CW Television Network.

Even though Paramount’s 1977 network plans were sunk, the studio continued preproduction on Phase II in hopes of selling the series directly to syndication, as it would Star Trek: The Next Generation a decade later. At the same time, however, Paramount executives found themselves under increasing pressure to respond to Star Wars, which was smashing box-office records and raking in hundreds of millions of dollars in merchandising revenue. It soon became clear that the studio’s best chance at a similar bonanza was Star Trek. That meant pulling the plug on Phase II and converting the project back into a feature film. The “In Thy Image” screenplay was retained as the basis for the movie but would undergo a new round of rewrites. Director Robert Collins, who had been hired to helm Phase II’s pilot episode, was discharged and replaced by Oscar winner Robert Wise. Although the official announcement wouldn’t arrive until the spring of 1978, by December 1977 (when gossip columnist Rona Barrett broke the story), Star Trek: Phase II had morphed into Star Trek: The Motion Picture.

With a potential blockbuster hanging in the balance, Paramount settled its suit with Nimoy, and Spock rejoined the crew of the Enterprise. (Gautreaux’s Xon character was promptly eliminated.) Expectations soared. Fans were jubilant over the mouth-watering prospect of a big-budget, big-screen Star Trek movie directed by the great Wise (who in 1951 had made The Day the Earth Stood Still). How could it fail? A Star Trek movie with such sterling credentials was guaranteed to be at least as wonderful as Star Wars, right? “Industry insiders hint that if the movie is successful, as it is sure to be, more features will be made” (italics added for emphasis), author Gerry Turnbull wrote in his 1979 book A Star Trek Catalog, published as fans breathlessly awaited Trek’s silver screen debut. “With more time, a bigger budget and some of the recent new frontiers crossed in the studio special effects field, the new Star Trek promises to be even more exciting [than the series].”

Unfortunately, Star Trek: The Motion Picture didn’t turn out quite the way fans dreamed. The production was beleaguered from the start, plagued by perpetual rewrites, cost overruns, and personality clashes between Roddenberry and Wise, among other problems. The movie finally debuted December 6, 1979, nearly five years after Paramount first commissioned a Trek screenplay from Roddenberry. But this lackluster effort squandered much of the fan loyalty Star Trek had built over the course of the past decade, and cost Roddenberry his previously unassailable position as master of his twenty-third-century universe. To survive, the franchise would have to make a second remarkable comeback.

For that story, tune in to Star Trek FAQ 2.0: Everything Left to Know About the Feature Films, the Next Generation, and Beyond, coming in 2013.