INTERNAL WATERS

OR INTERNATIONAL STRAIT?

THE NORTHWEST PASSAGE

AND THE COLD WAR

“Any American threat to this region . . . would be seen as an assault upon Canada’s very own heritage and identity.”

– THOMAS M. TYNAN, political scientist, 1979

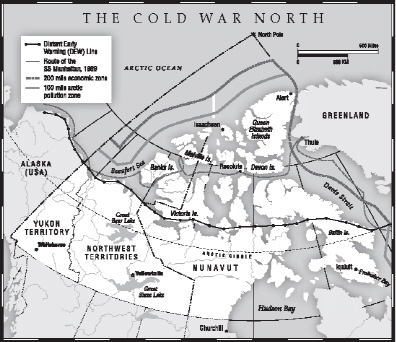

By the end of the 1960s, sovereignty concerns had shifted from the Arctic Archipelago—the offshore islands themselves—to the water (ice) passage between the islands. No one questioned Canada’s sovereignty over the lands and islands. The status of the waters between Canada’s Arctic islands, however, remained contentious. This should come as no surprise. Most land belongs to one state or another, and is thus subject to its laws. Land conflicts are thus about which particular state owns a particular territory. When it comes to water bodies, however, the first step is to determine whether a particular region falls under the control of a particular state or whether it belongs to everyone. In the case of the Northwest Passage—or Passages, because there are seven routes from the Chukchi Sea to the Atlantic Ocean through Canada’s Arctic islands—no states challenge Canadian ownership of the waters. The question is whether a strait runs through Canadian waters, in which case Canada has limits on how much it can control access to the Passage. The doctrine of the “freedom of the seas” holds that state jurisdiction ends at the coast, and the high seas are open to everyone. Thus the rules governing the seas must be made by the international community under international law. Canada has always considered the Northwest Passage to be internal waters. Others view it as an international strait stretching 2,850 nautical miles (3,280 miles, or 5,280 kilometres) from Greenland’s Cape Farewell to the Bering Strait in Alaska: 1,932 kilometres (1,200 miles) in the Canadian Arctic, 1,208 kilometres (750 miles) of Alaskan waters, and 1,449 kilometres (900 miles) of sea shared by Canada, Greenland and Denmark.1

The status of the Northwest Passage is a bone of contention between Canada and the United States. Canada maintains that the Northwest Passage is internal and thus subject to full Canadian “sovereignty,” with no right of transit passage to any foreign ship. Canada welcomes domestic and foreign shipping in its waters, but retains the legal right to control entry to and the activities conducted in its internal waters as if these were land territory. The United States insists that the Passage is an international strait with the right of transit passage. The Americans are inflexible on this issue. They see it as a potential commercial route between the Atlantic and the Pacific, and insist that commercial and their naval vessels need full access to it. There is more at stake for the Americans than Arctic waters, however, for if they accept the Canadian position, a precedent may be set for more strategically valuable straits in other parts of the world. For its part, Canada has refused to budge on the issue. Challenges to Canada’s sovereignty over Arctic waters have led Canadian governments to assert national rights, not by ringing claims over control of the Passage, but statements about the need to protect the delicate Arctic environment, the Inuit inhabitants of the North, and Canada’s icy inheritance.2 The federal government, hoping to demonstrate its commitment to defending Canadian sovereignty, ordered the Canadian Forces to “show the flag” and make a demonstration of Canada’s presence in the North. This was ironic, given that our closest military and economic ally was also our main opponent in the matter. Of course, and to no one’s surprise, the rhetoric about sovereignty and the military’s role was mostly bloviating, for the government was not willing to spend money on the equipment or personnel needed to turn hot air into reality, so when the American ships went home and the mini-crises faded, the speeches stopped. One thing had changed, however: sovereignty, though still largely symbolic, was now vested in the Canadian Forces and the Canadian Coast Guard who now replaced the RCMP as uniformed symbols of southern Canada’s willingness to safeguard its North from foes—and friends.

Canadian Confusion about Its Arctic Waters

Several commentators have noted how well defined Canada’s archipelago is geographically. “The Arctic Archipelago is really a prolongation of the main mass of [the] Canadian mainland North of the Hudson Bay in the direction of the North Pole, and the whole Archipelago is a clear unity with the continental mass,” a British diplomatic document stated in 1958. Rather than far-flung, scattered islands, Canada’s archipelago was more of “an island fringe off a mainland coast” far removed from the main commercial shipping routes or lanes. Its symmetrical, unitary appearance—“practically a solid land mass intersected by a number of relatively narrow channels of water”—distinguished it from other archipelagos around the world. (Neither Indonesia nor the Philippines are natural extensions of a continent, and the former is a long chain while the latter is a scattered group of islands. Both are on important shipping routes.3) Canadian External Affairs legal expert G. Sicotte wrote that the properties of Canada’s Arctic waters made them even more unique. They were not open to navigation without extensive Canadian assistance, and because of their ice cover resembled land more than the open seas that covered much of the globe:

A further consideration is that for most of the year the waters within the archipelago are completely frozen and form an integral part of the land areas. The sea ice is lived on and moved over in precisely the same fashion as the land masses. In fact, the sea ice is used to a greater extent for surface transportation and for hunting by the local inhabitants. For practical purposes the waters within the archipelago are, therefore, completely indistinguishable from the land during most of the year.

The Arctic Archipelago was not just physically and geographically united with the mainland. It was also closely tied to it economically. “The local inhabitants depend almost entirely on the resources of these waters for their livelihood,”4 Sicotte noted. But as late as the 1950s senior Canadian officials admitted that Canada had not clearly formulated its position with regard to sovereignty over the waters of the Arctic basin and the channels between its Arctic islands, both from “narrow national” and international points of view.5 This clarification would take decades to realize.

While Canadian nationalists are always quick to react to perceived threats to sovereignty, the nature and extent of Canada’s claims have always been ambiguous. The sector theory introduced in the early twentieth century—which theoretically extended Canadian control over all the lands and waters in a pie-shaped wedge— never became official policy. The voyages of British explorers formed the original basis for Canada’s claims in the Far North, and their concern was with land, not water. Bernier’s 1909 declaration also referred to lands and islands.6 Postwar military activities bolstered Canada’s legal claims to the mainland and archipelago. The Arctic waters were an entirely different story.

As historian Elizabeth Elliot-Meisel has written, Canada chose to focus its postwar naval efforts on fulfilling its NATO obligations in the Atlantic—antisubmarine warfare and protecting shipping lanes—rather than “showing the flag” in the Arctic. As a result, Canada’s early plans to control resupply of the Arctic weather stations were frustrated by a lack of resources.7 Instead, U.S. Navy and Coast Guard icebreakers, sometimes with Canadian observers aboard, gained operational experience probing Canadian Arctic waters. The USS Edisto became the first ship to transit the Fury and Hecla Strait and to circumnavigate Baffin Island. The American navy and Coast Guard had free rein in the High Arctic, given the lack of Canadian maritime activity in the region, and there is no evidence that they considered this “a form of watery trespass.” RCN Captain T.C. Pullen later noted that “somebody had to undertake ‘icebreaker reconnaissance,’ to make ‘observations of geographical, navigational and aviation interest,’” and to conduct hydrographic, meteorological, and electromagnetic experiments.8 Canada was incapable of performing these tasks, so they naturally fell to its superpower ally.

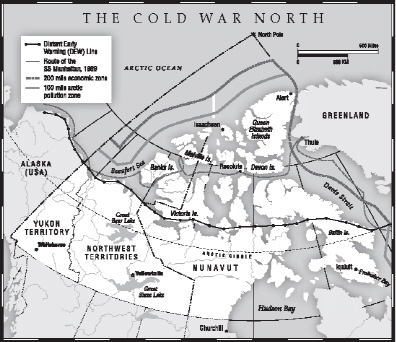

Beginning in 1948–49, Canada began to send naval vessels to the Arctic. That winter, five Royal Canadian Navy (RCN) ships undertook northern operations, and in January 1949 the navy let a contract to a Sorel, Quebec, shipyard to build a modified United States Navy Wind–class icebreaker capable of operating in the High Arctic. This ship, christened HMCS Labrador, which first ventured north in 1954 and was the first naval vessel to transit the Northwest Passage, resupplied weather stations and the DEW Line and served as a platform for scientific research. By agreement, U.S. Navy and Coast Guard vessels that supplied the DEW Line applied for and received Canadian waivers under the Canada Shipping Act before they proceeded.9 Captain Pullen, serving as the commanding officer of the Labrador at the time, was appointed U.S. Navy task group commander and reported to a U.S. Navy admiral during the 1957 sealift. One of his jobs was to ensure that three U.S. Coast Guard ships got safely through the Northwest Passage. “In those days, Canadians did not react as they would now to foreign encroachment in their Arctic waters,” he reminisced thirty years later; “but they had no cause. Great care was taken by the United States to respect Canadian interests. The joint security interest in the DEW line provided a shared incentive to devise arrangements that would avoid injury to either national position.”10 Indeed, journalists heralded Canada’s supply efforts as a “big gain for sovereignty” in that it “immeasurably strengthens our claim to the waters between the islands.”11

HMCS Labrador, the first and only Royal Canadian Navy icebreaker, provided icebreaking and operational support for the task groups supplying the DEW Line during its construction. Image courtesy of Canada Post Corporation

What were Canada’s claims? Senior government officials in Ottawa scrambled to find out. In the mid-1950s, the government requested copies of the original British title documents to the Arctic islands and began to study its rights to the waters in the archipelago.12 Before Canada formulated an official position, it had to ponder national goals and the international implications of claiming the waters and ice, as well as the underlying seabed and airspace above. “In addition to any advantages,” Gordon Robertson, the chairman of the Advisory Committee on Northern Development, explained, “sovereignty would imply certain obligations including the provision of such services as aids to sea and air navigation, the provision of any necessary local administration, and the enforcement of law”— in other words, the expenditure of public money. In response, the Soviet Union might either reject the claim or use it as a pretext to assert sovereignty over an even larger sector north of its mainland, and other countries would likely refuse to recognize a Canadian claim.13 Indeed, reporters recognized that “the Russians would like nothing better than to stir up a row between Uncle Sam and Canada over who owns the Arctic ice and sea on our side of the North Pole.”14 “It is almost a certainty that the United States would not concede such a claim and that the world at large would not acquiesce in it,” a legal appraisal at External Affairs explained. “It would therefore seem preferable not to raise the problem now and to implicitly reserve our position in granting permission for the U.S. to carry out work in Canadian territorial waters.” It made more sense for Canada to reach agreements with the U.S. on “the unstated assumption that ‘territorial waters’ in that area means whatever we may consider to be Canadian territorial waters, whereas the U.S. does likewise. These two views may not coincide but this need give rise to no difficulty until something happens which might involve Canada asserting jurisdiction over an area which the U.S. considers to be high seas. Then, and only then, would it be necessary for Canada to state its claim or by implication from silence, relinquish it or seriously weaken it.”15

The election of John Diefenbaker’s Conservatives to a minority government in 1957 and a majority in 1958 suggested that the federal government would pay more attention to prioritize the territorial and provincial Norths. Although much of Diefenbaker’s “northern vision” was foggy and was built upon the groundwork laid by his Liberal predecessors, his “roads to resources” policy led to the building of the Dempster and Mackenzie Highways, and his government continued to extend special social, educational, economic, and infrastructure programs to northern communities. Pearson, the Liberal Opposition leader, ridiculed the Conservatives for building roads “from igloo to igloo,” squandering federal resources that might have been better spent elsewhere—a disgraceful and partisan sneer from an essentially decent man that one hopes he soon regretted. Nevertheless, the number of government officials in the North grew during the early 1960s, for the burgeoning social welfare state in Canada included igloo dwellers as well as everyone else, and the new schools, housing, and a cornucopia of government programs meant many new civil servants living north of the 60th parallel. At the same time, the military’s relative presence diminished.16 So too did its actual activity levels, particularly in Arctic waters. In the mid-1950s, the Royal Canadian Navy had pondered whether, to bolster Canada’s claims, it should or could build nuclear-powered submarines or icebreakers.17 Instead, it got out of the Arctic game altogether. The RCN’s priorities lay with NATO antisubmarine operations, so in April 1958 it transferred the Labrador to the Department of Transport. Although criticized for this decision, the navy justified it on the grounds that the transfer of the Labrador would release 200 officers and men for duty in “fighting ships.”18 The government, focused on civilian administration and development initiatives, concurred.

The USS Skate surfaces at the North Pole, March 17, 1959. The prospect of submarine-launched ballistic missiles reduced the importance of the DEW Line, designed to deal with the threat posed by manned bombers. By permission of Ohio State University Libraries

“This great northland of ours is not ours because it is coloured red on a map,” Alvin Hamilton, the Conservative minister of Northern Affairs, told the House of Commons on July 7, 1958. “It will only be ours by effective occupation.” Nevertheless, what boundaries did Canada actually claim? And who was effectively occupying the Arctic waters? No one had a concrete answer, but the question of maritime sovereignty re-emerged when the U.S. launched icebreaker construction programs in the fifties. In 1958, the nuclear-powered submarine USS Nautilus crossed under the polar ice cap in its voyage from Pearl Harbor to Iceland. International law expert Maxwell Cohen wrote in Saturday Night magazine:

[N]ow that the Nautilus has made the full undersea voyage that Jules Verne visualized for his readers and Sir Hubert Wilkins actually planned a few years ago—with much less manageable equipment—the Arctic seas have become another arena among the many that now provide military and strategic vantages in the continuing contest of East and West.

For it will not be lost upon the Russians that atomic-fueled submarines can roam beneath the ice pack, not only under that portion of the pack regarded as the North American “sector” but also within the Soviet angle of “presumed” authority as well. How dangerous this may be to either side, with submarine-launched missiles such as the Polaris having a 1,500-mile range—and perhaps in the near future a 2,000 and 3,000–mile range—requires no great military imagination to understand. So the Arctic waters, now with Arctic air-space, are all a potential battleground while the romance of exploration and dog-team yields to the cruder demands of polarized power.19

The submarine USS Seadragon passed westward through the Northwest Passage in 1960, and the USS Skate transited eastward two years later. This tied back to Cold War technology. If radar systems like the DEW Line could detect bombers, then new strategic delivery systems would be deployed to change the strategic game. The Arctic Ocean, covered by a dense (and noisy) ice pack, offered protection from aerial surveillance and sonar detection. Using this logic, the U.S. Navy—or the Russians—could use the polar region to creep silently under the sheltering ice, and get close to enemy territory to launch a nuclear attack using submarine-launched ballistic missiles (SLBMs). Commander James F. Calvert of the Skate told public audiences that the United States could “best hold its world leadership by gaining superiority in the Arctic,” and that the Arctic waters would soon become an “entirely nuclear sub-ocean.” While this was not official policy, it indicated to Canadian officials that the American government would take “ever increasing interest” in the region.20 Soon afterwards, U.S. international lawyers began arguing that the Arctic seas constituted international territory, belonging not wholly to Canada, or the Russians, or anyone else.21

What was Canada’s stance? When in 1963 Ivan Head, a lawyer with the Department of External Affairs, surveyed the official record, he found confusion. “Few Canadian policies have been so inconsistently or unhappily interpreted over the years as that pertaining to the Arctic frontiers,” he lamented. In 1946, Lester Pearson, then Canadian ambassador to the U.S., had written that Canada’s northern territory included “the islands and frozen seas north of the mainland between the meridians of its east and west boundaries extended to the North Pole.” Then, a decade later, Jean Lesage, the minister of northern affairs, stated that Canada’s sovereignty extended to all the Arctic islands, but that “the sea, be it frozen or in its natural liquid state, is the sea; and our sovereignty exists over the lands and over our territorial waters.” Did this include the Arctic waters? Prime Minister Louis St-Laurent responded a few months later that his government considered the waters between the Arctic islands to be “Canadian territorial waters.” In June 1958, Alvin Hamilton clarified the position: “The area to the north of Canada, including the islands and waters between the islands and areas beyond, are looked upon as our own, and there is no doubt in the minds of this government, nor do I think in the minds of former governments of Canada, that this is national terrain.” Hamilton’s assertion rested on the idea of “effective occupation,” which the government believed was consistent with international law.22

The essential issues had to do with international law. Maritime boundaries differ from territorial boundaries because they not only mark the place where one state ends and its neighbour begins, but also separate a state’s jurisdiction from parts of the earth which belong to the world community at large.23 There are three distinct types of water in international law that bear directly upon the Northwest Passage:

1. the “high seas,” the oceans of the world, are international waters over which no individual state can control the shipping of other states. In short, the high seas belong to everyone and no state can claim them as their own. They are free to everyone.

2. “internal waters” over which the state has full sovereignty. There is no right to innocent passage—defined by the UN Convention on the Law of the Sea as passage that is “not prejudicial to the peace, good order or security of the coastal State”—through internal waters, which are either enclosed by land, harbours and waters surrounding coastal islands, or waters lying to the land side of baselines drawn by the state. The “mean low-water line” on the coast serves as the normal “baseline” to determine the outer limit of internal waters, measured out from this baseline. Of course, few coastlines are straight. So states have also drawn “straight baselines” across the mouths of deeply indented bays or archipelagos bordering a coast, claiming that the waters within them are also subject to full state authority. They have also claimed “historic title” to waters like Hudson Bay, but the question of “historical waters” has not yet been settled legally.

3. “territorial waters,” coastal waters of a country that extend seawards from either the coast or the baselines that enclose the internal waters of a state. In the nineteenth century, the U.S. and Britain adopted a 3-nautical-mile (3.45 miles or 5.55 kilometres) limit on territorial waters, which became a standard in many parts of the world. By the 1960s, however, most states were claiming that their territorial sea extended up to 12 nautical miles (13.8 miles, or 22.2 kilometres) off the coast, and some Latin American countries much more than that. The coastal state has limited authority over the “territorial sea” that is similar to sovereignty, except that foreign vessels have a right of “innocent passage” through territorial waters of any state. This right to innocent passage does not extend to the airspace above territorial waters, which falls under the sovereignty and jurisdiction of the state.

These definitions, coupled with the body of rights, privileges, practices, and customs that have evolved since the Middle Ages, form the basis of “the Law of the Sea.”24

The status of the Northwest Passage can be read in different ways according to these criteria. Since 1985, Canada claims that the waters within the archipelago are historic internal waters that are part “of the natural unity of the Canadian Arctic Archipelago.” In order for Canada’s stance to hold, it has to withstand the challenge that the Northwest Passage constitutes an international strait: a body of water linking one area of the high seas to another, or connecting the high seas to a territorial sea that is used for international navigation. In straits used for international navigation, ships have a right to transit passage. The extent to which a passageway must be used for international navigation before it constitutes an “international strait” is unclear in international law, but evidence of foreign shipping is certainly necessary to claim that a waterway is an international strait. Furthermore, Canada maintained that entry into its Arctic waters could not be classed as “innocent passage” because the dangers of navigating ice-filled waters inherently threatened the northern ecosystem. This helps to explain why Canada moved cautiously to follow controversial international trends to widen its territorial sea and establish a contiguous zone of limited jurisdiction beyond that limit.25

In the 1960s, Lester Pearson’s Liberal government continued to officially endorse a 3-mile (4.83-kilometre) territorial sea, but it also announced its intention to expand its control beyond those limits: “Following the failure of the 1958 and 1960 conference on the Law of the Sea to reach agreement on the breadth of the territorial sea and fishing, Canada decided to implement by unilateral action a nine-mile fishing zone adjacent to its three-mile territorial sea,” an External Affairs statement declared on January 21, 1965. Although the government introduced legislation to this effect and instituted an exclusive fishing zone based upon straight baselines along the east and west coasts, it retreated from making any moves to do the same in the Arctic. The government knew that the U.S. would object to any action to any internal waters claim or to straight baselines, as it did everywhere in the world, but it hoped that the Americans might support an extension of Canada’s claim to Arctic waters for reasons of defence and national security. The U.S., however, reacted sharply because any move in the Arctic could set a dangerous precedent. The Canadian government thus retreated from its plans, and Canada did not officially issue any geographical co-ordinates to delineate its claim to baselines in the Arctic for another twenty-three years.26

By 1970 it was resource development, not superpower security threats, that put the competing Canadian and American visions on the front burner. The search for petroleum had begun near Point Barrow, Alaska, during the Second World War, and large-scale exploration for new fields began in the Queen Elizabeth Islands in 1959. By the mid-1960s, an exploration boom drew unprecedented attention to the Beaufort Sea north of Canada and Alaska. Oil companies organized syndicates, secured exploration permits, conducted geological mapping and geophysical prospecting, and drilled at a few sites in the Canadian archipelago. “This has presented the first opportunities for use of part of the Northwest Passage for strictly commercial shipping,” Trevor Lloyd noted in Foreign Affairs in 1964. “Even if oil in commercial quantities were to be discovered shortly, there might well be considerable delay before it could reach world markets as the method of transportation is still to be determined.”27

When Robert Anderson, chairman of the Atlantic Richfield Company, announced the discovery of one of the world’s largest petroleum deposits on the north slope of Alaska in 1968, Lloyd’s hypothetical scenario became a reality. What was the most expeditious and cost-effective manner to get the estimated ten billion barrels of oil to southern U.S. markets? The oil industry immediately launched pipeline and transportation studies to determine the feasibility of various options, including the possibility of using tankers to transport oil through the Northwest Passage to East Coast refineries. In 1969, Atlantic Richfield, British Petroleum Company, and Standard Oil floated a plan to send an ice-strengthened vessel through the Passage, stating that “if successful, the test could result in the establishment of a new commercial shipping route through the Arctic region with broad implications for future Arctic development and international trade.”28

The Manhattan voyage of 1969 had broad implications for Canadian-American relations, and has since assumed mythic proportions. If Canada’s approach to Arctic diplomacy generally had, to this point, been marked by quiet diplomacy between close allies, its new activism signalled the changing times. By the late 1960s, Canada was differentiating its foreign policy from that of its southern neighbour. The Canadian social welfare state that blossomed during the Pearson years seemed very different from the American “warfare state” embroiled in Vietnam. Canadians now worried about their sovereignty for new reasons: the vulnerability of their economy, which was inextricably bound to American owners and markets, and disillusionment with prospects for continental cooperation generally.29 “At no point had Canada in the past abandoned its sovereignty and jurisdiction in the Arctic. Indeed, it had taken considerable pains to affirm it diplomatically,” political scientist Thomas Tynan explained. “In an era of heightened concern with Canadian sovereignty across the board, however, matters affecting the Arctic were drawn into the public sector and brought to high visibility. They could no longer be suitably dealt with through simply informal, or closed, diplomatic channels. A bold statement of national interest in the Arctic was needed to replace a merely quiet affirmation of it.”30

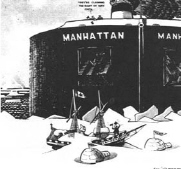

When the S.S. Manhattan tested the feasibility of carrying Alaskan oil to the American eastern seaboard through the Northwest Passage, Canadian nationalists reacted with alarm. Duncan Macpherson’s cartoon in the Toronto Star showed how limited Canada’s Arctic capabilities were. Copyright: Estate of Duncan Macpherson. Reprinted with permission—Torstar Syndication Services.

The Manhattan was an ice-reinforced double-hulled tanker converted into the world’s largest icebreaker, designed to test the feasibility of carrying oil from Prudhoe Bay north of Alaska to the American eastern seaboard. In the months before the voyage, oil company executives and the U.S. Coast Guard consulted with Canadian officials and even requested that a Canadian icebreaker accompany the ship during its transit. “Canada agreed, and gave the voyage full concurrence and support,” navy captain Thomas C. Pullen observed. He served as the Canadian government’s representative on the Manhattan during its voyage, acted as the Department of Transport’s link with the tanker, and served as the ice adviser. The Canadian government also provided aerial ice reconnaissance and an on-board ice observer. “In return for this substantial Canadian participation,” Pullen explained, “the valuable data on ice and ship performance acquired during the voyage were to be shared with Canada.” Only six of the Manhattan’s forty-five tanks actually contained oil, so the environmental risk was minimal. Equally important, Pullen stressed that the Manhattan’s master, Roger Steward, “was meticulous in matters of protocol, and flew the Canadian flag as appropriate,” and “the sponsors of the voyage did their best to offend no one.”31 Pullen was as surprised as the Manhattan’s crew when Canadian press reports began to depict the voyage as a direct challenge to Canada’s Arctic sovereignty. He must have been unfamiliar with the ways of journalists.

“The legal status of the waters of Canada’s Arctic archipelago is not at issue in the proposed transit of the Northwest Passage by the ships involved in the Manhattan project,” Pierre Elliott Trudeau explained to the House of Commons on May 15, 1969. “The Canadian government has welcomed the Manhattan exercise, has concurred in it and will participate in it.”32 The government’s position was that there were no sovereignty challenges to Canada’s northern lands, territorial waters, or the continental shelf. But the U.S. refused to ask Canada permission to enter the Northwest Passage because this could be construed as recognition of Canadian internal waters. The nationalist media jumped on this attitude as a direct affront to Canada’s claims, even though the Canadian government had still not defined “strait baselines” in the Arctic to enclose what politicians and journalists seemed to consider “internal waters.” For all practical purposes, Humble Oil’s request for Canadian co-operation seemed to imply that the passage was Canadian, even if it left official responses about sovereignty questions to the U.S. State Department, which would, of course, not say as much.33

Mitchell Sharp, the Canadian secretary of state for external affairs, responded in the Globe and Mail that “the Manhattan project would not have been possible without . . . extensive Canadian input, consisting of preparatory studies extending for many years over a vast area of the North. . . . It is wholly misleading, therefore, to portray the Manhattan passage as a test of Canada’s sovereignty in the Arctic, the issue simply does not arise.” He stressed that this was “no time for wide-ranging assertions of sovereignty—rather Canada must concentrate on specific objectives, the most important of which is the opening up of the Canadian Arctic region for development.”34 Unconvinced, journalists fed public anxieties about American encroachments and continued to press the government to take a strong stand, particularly after the owners of the Manhattan planned a second voyage the following year to test an alternate route. “Manhattan’s two voyages,” law expert Maxwell Cohen astutely noted, “made Canadians feel that they were on the edge of another American . . . [theft] of Canadian resources and rights which had to be dealt with at once by firm governmental action.”35

In the Manhattan case, what was quickly perceived as a U.S. sovereignty challenge provided an important connection to the larger theme of Canada’s custodial responsibilities in the North. “If the Manhattan succeeds,” a Globe and Mail editorial predicted on September 9, 1969, “other oil laden vessels will follow in her wake. Before that happens Canada must be ready to receive and control them; for it is Canada’s northland that would be devastated if the ice won and the tanker lost.” What if a supertanker ran aground along the Northwest Passage? The Liberian tanker Arrow had run aground off Chedabucto Bay, Nova Scotia, in early 1970, discharging nine million litres of oil and polluting hundreds of kilometres of shoreline. Canadian scientists suggested that a similar accident in the Arctic Ocean would have catastrophic effects.36

In contrast to previous characterizations of the Arctic as an area through which to pass to get somewhere else, or as distant strategic space, or as a treasure-laden frontier, the idea of an ecologically delicate Arctic now became a convenient reason to extend Canadian jurisdiction northward. In his October 1969 Throne Speech to Parliament, Trudeau explained that

Canada regards herself as responsible to all mankind for the peculiar ecological balance that now exists so precariously in the water, ice and land areas of the Arctic Archipelago. We do not doubt for a moment that the rest of the world would find us at fault, and hold us liable, should we fail to ensure adequate protection of that environment from pollution or artificial deterioration. Canada will not permit this to happen. . . .

Part of the heritage of this country, a part that is of increasing importance and value to us, is the purity of our water, the freshness of our air, and the extent of our living resources. For ourselves and for the world we must jealously guard these benefits. To do so is not chauvinism, it is an act of sanity in an increasingly irresponsible world. Canada will propose a policy of use of the Arctic waters which will be designed for environmental preservation . . . as a contribution to the long-term and sustained development of resources for economic and social progress.37

The prime minister’s environmentalist spin on lingering nationalist concerns was innovative. The decision to frame foreign, particularly American, activities, as a threat to Canada, violating the country’s territorial integrity and jeopardizing the broader human right to live in a “wholesome natural environment,” was cited as a reason for the government to adopt extraordinary means to protect its environmental interests with unprecedented haste.38

In April 1970, the Liberal government introduced two bills into Parliament that indicated a new “functional” approach to Canadian sovereignty. Bill C-202, the Arctic Waters Pollution Prevention Act (AWPPA), was designed to allow Canada to regulate and control future tanker traffic through the Northwest Passage by creating a pollution-prevention zone 100 nautical miles (115 miles or 185 kilometres) outside the archipelago as well as the waters between the islands. “The Arctic Waters bill represents a constructive and functional approach to environmental preservation,” Secretary of State for External Affairs Mitchell Sharp asserted during the debate in the House of Commons. “It asserts only the limited jurisdiction required to achieve a specific and vital purpose.” It was not a full declaration of sovereignty. Rather, by putting aside but not renouncing any claim to sovereignty, the government claimed jurisdiction to ensure that “dirty” tankers did not pollute Canadian waters.39 Bill C-203, the Territorial Sea and Fishing Zone Act, extended Canada’s territorial sea from 3 to 12 miles (4.83 to 19.32 kilometres), which meant that any foreign vessels entering the Northwest Passage through Barrow and Prince of Wales Straits would have to cross waters subject to Canadian control. In explaining the bills in the House of Commons, Trudeau said that “the important thing is that we . . . have authority to ensure that any danger to the delicate ecological balance of the Arctic is prevented or preserved against by Canadian action. . . . It is not an assertion of sovereignty, it is an exercise of our desire to keep the Arctic free of pollution.”40 Both bills passed Parliament unanimously.

A key aspect of both pieces of legislation was that Canada did not claim outright sovereignty over the Northwest Passage. Instead, it asserted “functional” sovereignty: jurisdiction to regulate certain activities in Arctic waters. Trudeau acknowledged that, while Canadian governments considered the archipelago and the waters between the islands to be “national terrain,” not all countries would accept that these were “internal waters over which Canada has full sovereignty. The contrary view is indeed that Canada’s sovereignty extends only to the territorial sea around each island.”41 Although this was a statement of the obvious, the prime minister seemed to highlight the uncertainty surrounding Canada’s position. Because the Arctic Waters Pollution Prevention Act did not assert full Canadian sovereignty, critics alleged that the government was actually diminishing Canada’s sovereignty claim. Despite growing clamour from the Opposition benches and the popular media, Trudeau refused to concede to the “ultranationalists” and issue a straightforward declaration of sovereignty. His course, he suggested, was that of “legal moderation” with a clear focus on the popular issue of environmental protection.42 After all, the prime minister explained, “to close off these Arctic waters would be as senseless as placing a barrier across the entrance to Halifax or Vancouver harbour.” The government’s commitment was to actively develop the Passage for safe navigation by any vessel that followed Canadian regulations and safety standards.43 External Affairs documents, recently acquired under Access to Information, suggest that Canada’s long-term objective was to lay the groundwork to apply the straight baseline to the system of the archipelago, even though this was strongly opposed by the U.S.44 Indeed, as international lawyer Donald McRae observed, the legislation was a “manifestation of sovereignty” that was ultimately accepted by the international community, and thus “helped to consolidate Canada’s authority over the waters of the Canadian Arctic Archipelago.”45

Prime Minister Trudeau in Igloolik, 1970. In response to the Manhattan voyage, the government adopted a “functional approach” to sovereignty in the Northwest Passage: it did not claim outright sovereignty but regulated commercial activities. Glenbow Archives NA-4141-1

Political scientist David Larson observed that the U.S. response, issued a week after Canada announced its new legislation, revealed how “this confrontation brought the United States and Canada squarely into conflict with each other over a number of law of the sea issues.” The American position held that “international law provides no basis for these proposed unilateral extensions of jurisdiction on the high seas, and the United States can neither accept nor acquiesce in the assertion of such jurisdiction.” The explanation was based on strategic considerations. If the U.S. did not oppose Canadian action, then it “would be taken as precedent in other parts of the world for other unilateral infringements of the freedom of the seas.” This could affect merchant shipping, naval mobility, and heighten the potential for international controversy and conflict.46 “We can’t concede them the principle of territoriality or we’d be setting a precedent for trouble elsewhere in the world,” a Department of State official had previously told the Toronto Star. All bodies of water connecting the high seas were international, making this an international issue that could “not be resolved by Canada’s attempt to apply domestic law to ships plying these passageways.”47

The Canadian position stressed that the Northwest Passage was not “high seas.” While it acknowledged U.S. interests in free transit through international straits around the world, it maintained that the Northwest Passage was not an international strait and therefore could not serve as a precedent for elsewhere. The Canadian government thus proceeded with the legislation, despite American protests and counterproposals.48 The Canadian ambassador in Washington and other senior government advisers had met with State Department officials in March 1970 and promised that American views “would be taken into account.” It was clear, however, that “the Canadians were not interested in having [American] comments, suggestions, modifications, or alternatives,” Theodore L. Eliot Jr. explained to President Nixon. “They admitted their embarrassment in giving us so little advance notification. It is equally clear that the Canadian presentation was in fact only a notification and that they did not anticipate real bilateral consultations before the legislation is a fait accompli.” Canada said it was willing to open discussions to secure international confirmation for the legislation after it was in place, but not before. There was little ground for compromise. “The proposed Canadian legislation is in our view entirely unjustified in international law,” Eliot explained. “There is no international basis for the assertion of a pollution control zone beyond the 12-mile contiguous zone; there is no basis for the establishment of exclusive fishing zones enclosing areas, of the high seas; and there is no basis for an assertion of sovereignty over the waters of the Arctic archipelago. The proposed Canadian unilateral action ignores our frequent request that Canada not act until we have had an opportunity for serious bilateral discussions.”49

Rather than convincing Canadians to back down, American opposition “only buttressed popular support” for Ottawa’s action. Thomas Tynan explained that it came “to represent a firm Canadian stand in the face of the American rush into the Canadian Arctic.” Newspapers like the Globe and Mail took up the issue and tied it to diverging Canadian-American interests more generally:

The United States objects to the Canadian bill. Let it. The ships that pose the greatest threat of oil pollution to the Arctic are American. And the Americans have been something less than a driving force in pushing for realistic international controls.

This issue has a significant potential for confrontation between our two nations. But Canadians should realize that we are different nations with different interests and different purposes. Inevitably, as we grow and develop, there are going to be conflicts.

And so Canadians should begin to prepare for a moving apart, not only on this issue, but many others affecting our economy, our culture, our approach to international affairs.50

The Northwest Passage became a litmus test for Canadian sovereignty. Here again was Canada’s official “passive-reaction” tradition in response to perceived American threats to its northern sovereignty.51 In the mid-1970s, it seemed, the stakes were higher than ever before.

If Canada’s actions seemed hesitant to some commentators, they were ahead of international law and thus represented an important change in official direction. Legal advisers warned the government that the AWPPA might not stand up to an international challenge in the International Court of Justice. Nothing in customary law or in the UN Law of the Sea agreements to that time gave a country the right to implement pollution controls beyond its territorial waters. As a result, in 1973 the government reserved its pollution and fisheries legislation from the compulsory jurisdiction of the International Court of Justice—meaning it would not allow the Court to strike it down—thus pre-empting any foreign challenge to its legislation.52 That same year, the Canadian Bureau of Legal Affairs issued the first official claim that the waters between the islands within the archipelago were “internal waters of Canada, on historical basis,” a claim followed by a ministerial statement to the Standing Committee on External Affairs and National Defence two years later.53 Through these actions, political scientists John Kirton and Don Munton explain, the government had accomplished “one of the largest geographic extensions of the Canadian state’s jurisdiction in the country’s history.” It had also broken “with the liberal-internationalist traditions that had dominated Canadian foreign policy since the Second World War.”54

Claiming jurisdiction was one thing; implementing it was another. How would Canada enforce its laws if foreign vessels decided to challenge Canadian controls? On April 3, 1969, Trudeau had identified “the surveillance of our own territory and coastlines—i.e., the protection of our sovereignty”—as the first priority in his government’s defence policy. However, the specific nature of the Canadian Forces’ role in asserting sovereignty remained ambiguous.55 What exactly could the military accomplish as sovereignty soldiers? On April 30, 1969, Eric Wang, of the Department of External Affairs, emphasized that the sovereignty question related to Arctic waters was “a legal, political and economic problem. It is not a military problem. It cannot be solved by any amount of surveillance or patrol activities in these channels by Canadian Forces.” Increasing Canada’s military or non-military surveillance activities would neither strengthen its legal case nor undermine that of the U.S.56

The following year, M. Shenstone, of External Affairs’ North American Defence and NATO Division, was still concerned because the rationale for the government’s new defence policy had never been clarified in any classified or published document. “We are not aware of any current intelligence estimates forecasting a need for a greater level of military surveillance and capability in the North,” he explained, but recent announcements showed that “the Canadian Armed Forces are moving in the direction of a significant reallocation of resources towards the North and away from other areas such as NATO Europe.”57 Why? The government insisted that there was no challenge to Canada’s northern lands, territorial waters, and seabed, and that the only likely challenge was to the Northwest Passage—one that would be commercial and peaceful. “At the same time, Canada’s Armed Forces had been given the primary mission of protecting sovereignty, with particular emphasis on the North,” Ken Eyre explained. “Yet, by the government’s own admission, the only possible challenge to Canadian claims—and that in a very specific and restricted area—was mounted not by an international rival or threat, but by the United States, Canada’s closest ally and major trading partner.” Given this confusion, he was not surprised that both the Canadian Forces and the broader public had difficulty discerning what the military’s role should actually be in this “new North.”58

Strategic planners at National Defence headquarters in Ottawa insisted that “apart from the threat of aerospace attack on North America, which can be discounted as an act of rational policy, Canada’s geographic isolation effectively defends her against attack with conventional land or maritime forces.”59 Who, after all, was challenging our sovereignty, and what role could the armed forces play? The military eventually identified three classes of northern “anomaly” that could undermine Canadian control. The first, “tactical anomalies,” were acts by foreign militaries such as overflights of Canadian territory, submarine or warship transits of Canadian internal waters, or the unlikely prospect of a military incursion in the North. The second, “commonweal anomalies,” included disasters that threatened the ecological or social stability of the region and its people, such as floods, pollution, or air crashes. The third and most likely class, “sovereign anomalies,” included foreign companies or individuals who, acting without direct government approval, contravened Canadian law but probably would not be detected given the vastness of the Arctic. Senior officials determined that the Canadian Forces should be able to respond to each of these anomalies from detection, to reconnaissance, to enforcement. In short, the military had to rethink its surveillance and reconnaissance role to incorporate non-evasive, non-hostile, and often co-operative “targets” that might undermine Canadian sovereignty.60

These were not primarily combat roles, of course, but reflected the complexities that the government faced in asserting sovereignty in the North. The minutes of an interdepartmental committee meeting on the Law of the Sea explained that

The role of the forces is in many respects complementary to that of the civil authorities, but the proportionate requirement for the military is generally higher in the more sparsely settled regions until a more advanced stage of economic and social development is reached and the associated expansion of civil agencies and resources occurs. Similarly where shortage of civil resources for the policing of waters off the coasts occurs, this requires an expanded role for the armed forces.

The Government’s objective is to continue to occupy effectively and to have surveillance and control capability to the extent necessary to maintain authority over all Canadian territory, airspace and waters off the coasts over which Canada exercises sovereignty or jurisdiction. This involves a judgment on the challenges which could occur and on the surveillance and control capability required in the circumstances.

It is a complicated problem. The area to be covered is vast, in certain regions facilities are limited and weather conditions are often adverse. Indeed Canada has the longest coast line of any country in the world and fronts on three oceans. The problem would in a sense be simpler if defence were restricted to dealing only with the more traditional security threat of direct military attack from a predictable enemy. Instead challenges could arise in more ambiguous circumstances, from private entities as well as foreign government agencies. Incidents may involve, for instance, a fishing vessel, an oil tanker or a private aircraft. But the principle involved is well established. By creating a capability for surveillance and control which is effective and visible, the intention is to discourage such challenges.61

Other federal departments and agencies had lead roles in these areas, but the military bore ultimate responsibility for Canadian sovereignty. It had only meagre capabilities, however, to answer any challenges.

Defence initiatives also had to reflect Canada’s broader northern policy agenda. A memorandum to Cabinet in early 1971 stressed that “the North has caught the imagination and attention of all Canadians and some people outside, which underlines the importance of the ‘image of Canada’ reflected in Government policies and activities there.” By 1965, it argued, Canadian policy in the North had shifted from “almost exclusive emphasis on defence matters to increasing concentration on people programs” such as housing and municipal services, education, health, and welfare. By the late 1960s, the focus had turned to development. Then it had shifted to environmental protection. The government was now committed to “a systematic movement of all programs toward a steady pace and rhythm for total development in the territories.” In addition to maintaining sovereignty and security, the federal government identified three main goals: the provision of a higher standard of living for northern residents; the maintenance and enhancement of the northern environment; and the encouragement of economic development. The government’s priority was to strike a balance between people, ecology, and resource exploitation, with a primary emphasis on the first two considerations.62 The Canadian Forces would have to operate within this new context.

The new look for Canada’s Arctic patrols was “to see and be seen.”63 In 1970, naval vessels sailed into Arctic waters for the first time in eight years, initiating annual northern deployments or NORPLOYs that continued through the decade. Maritime Command began Arctic-surveillance patrols using medium- and long-range patrol aircraft, performing such tasks as surveying northern airfields, examining ice conditions, monitoring wildlife and pollution, and documenting resource extraction and fishery activities. The army began regular, small-unit “Viking” Arctic training patrols, as well as elaborate paratroop assault exercises in the archipelago involving the Canadian Airborne Regiment. These activities were transient and limited. So too were long-range air surveillance patrols (which were limited by weather and the lack of northern airfields), and naval ships confined to select waters only in ice-free months. To provide a permanent presence, the Canadian Forces set up a new Northern Region headquarters in Yellowknife in May 1970, which boasted that it was responsible for “the largest single military region in the world.” To cover 40 percent of Canada’s land mass, the only resources at Northern Region’s direct disposal were the headquarters staff, two Twin Otter aircraft, 600 to 700 Rangers in units that were being resurrected after their abandonment during the 1960s, and a few hundred personnel at communications research and radar stations.64

Strategist Ken Eyre has shown that the government not only avoided stationing regular forces in the North, it did not obtain any new equipment for the forces, such as special reconnaissance aircraft or surveillance equipment, ice-capable ships or submarines for the navy, or all-terrain vehicles for the army. “To protect sovereignty in the North, the government adopted a policy strikingly analogous to the situation that existed in Canada at the time of the 1922 Eastern Arctic Expedition,” he noted. “In the 1920s, Canada established sovereignty in the Arctic with a symbolic presence of the Royal Canadian Mounted Police. In the 1970s, Canada prepared to protect that same sovereignty with a symbolic presence of the Canadian Armed Forces.” An important difference, however, was that the southern military units that operated in the North were transient and their roles in national defence included much more than northern training. They were not able to stay for long periods, as the Mounties had done. Nevertheless, by 1975, “the Canadian Forces had re-established themselves in the North to an unprecedented degree.” Perhaps more importantly, Eyre observed, “for the first time, the Department of National Defence was prepared to admit that the North had an intrinsic value to the country as a whole and that a military presence was required in the area.”65

The Canadian Rangers (local residents who received a rifle, ammunition, and basic training) gave the military a permanent presence along Arctic coastlines. Here, Ranger Raymond Mercredi fires a rifle in a Nanook Ranger exercise. DND photo ISC88-367

The intrinsic value of the region came to the fore during discussions surrounding the proposed Mackenzie Valley Pipeline. The difficulties encountered by the Manhattan convinced the oil industry that the Northwest Passage route was not commercially feasible at that time. Instead, U.S. president Richard Nixon authorized construction of the Trans-Alaska Pipeline from Prudhoe Bay on Alaska’s North Slope to the Gulf of Alaska on the state’s southern coastline. From there, tankers would transport the oil along the Canadian west coast for refining and distribution in the southern United States. Canadian officials, worried about the environmental and economic consequences of a tanker accident and oil spill in Juan de Fuca Strait or the Strait of Georgia, lobbied the American industry and government officials to try to convince them that an overland pipeline through the Mackenzie Valley region made more sense. J.J. Greene, the minister of energy, mines and resources, explained to the Vancouver Men’s Canadian Club in February 1971 that

the Canadian Government is not opposed to the construction of oil and gas lines from Alaska through Canada to the continental United States. . . . [T]he United States oil industry has been too hasty and too unplanned in its decision to move Alaska North Slope oil across Alaska from Prudhoe Bay to Valdez and then by sea to receiving points in the U.S. Northwest. . . . To us it appears that an oil line from Alaska through Canadian territory would have the advantage of ruling out a vulnerable tanker link to markets and would provide more economic transportation of oil to the U.S. Midwest. . . . Canada, for its part of the bargain, would undertake to ensure the uninterruptibility of the flow of Alaska oil down a Canadian “land bridge” line equivalent in volume to any flow which could be put through the [Trans-Alaska Pipeline system] lines.66

The Americans decided against the Canadian pipeline route because it was not “the most cost efficient, secure, economically beneficial and, in particular, expeditious.”67 The Trudeau government continued to explore the option, anticipating Canadian petroleum discoveries. Indeed, the prime minister likened the proposed Mackenzie Valley Pipeline to the Canadian Pacific Railway, which had opened the West after Confederation. The ensuing debate over the pipeline, however, signalled that the future of the northern frontier could no longer be decided in government or corporate boardrooms.