THE FINAL RACE

TO THE NORTH POLE:

CLIMATE CHANGE, OIL AND GAS

AND THE NEW BATTLE FOR THE ARCTIC

“The question of Arctic sovereignty is not a question. It’s clear. It’s our country. It’s our water. It’s the ‘True North strong and free’ and they are fooling themselves if they think dropping a flag on the ocean floor is going to change anything.”

– PETER MACKAY, Minister of National Defence (2007)

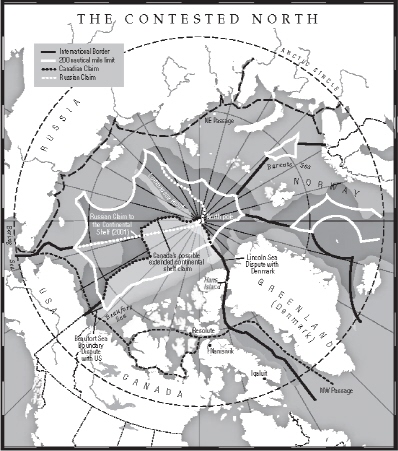

Suddenly, after decades of being coffee-table conversation for academics, the Canadian Arctic is front-page news—in the New York Times, in Time magazine, and in papers around the world—and, because of the melting ice cap that according to Al Gore threatens to drown the coastlines of the world, has a prominent place in his documentary, An Inconvenient Truth. Overnight the Far North has become the canary in the mine shaft, a symbol of the impending catastrophe of global climate change. But there’s more to the issue than melting ice. Developers lust after the oil, gas, and mineral potential of the region; there may be billions of dollars to be extracted from what have long been seen as ice- and snow-covered wastes. Russian submarines patrol the Arctic seabed, and a revitalized Russia is scientifically staking its extended continental shelf. Indeed, all Arctic Ocean coastal states have or are making submissions to delineate the outer limits of our respective continental shelves. Russian submarines have been there for years, navigating the high seas, as they have every right to do under international law. But that same Russia, written off a few years ago as a declining superpower, is now flying patrols in the Far North, foreshadowing a remilitarization of the Arctic. Is this a new Cold War, the Hot Arctic, or some combination of both? Whatever the cause and the outcome, the Arctic has moved towards the centre of the international stage, fuelling misguided debates about the best means of protecting Canadian sovereignty in an area over which we previously had no rights. Confused by press reports of land extension and possible confrontation, the public’s concern is really driven by its misunderstanding about the existing process. All Arctic states, Russia included, are engaged in a legally established United Nations process to delimit their extended continental shelves. States are not really enlarging their territory, but identifying the seabed area outside their 200-nautical-mile (230 miles, or 368 kilometres) economic zones where they have the exclusive right to exploit resources. Nevertheless, Canadian anxieties speak to the heightened tempo of activity and uncertainty in a changing Arctic region that will soon be more accessible to a resource-hungry world.

Climate Change and the Threat to the North

In a strongly worded October 2007 op-ed piece in the New York Times, Canadian scholar Thomas Homer-Dixon offered a sobering commentary on the threat posed by global warning. He used the Arctic as the symbol for the critical challenge facing the international community:

The vast expanse of ice floating on the surface of the Arctic Ocean always recedes in the summer, usually reaching its lowest point in the last half of September. Every winter it expands again, as the long Arctic night descends and temperatures plummet. Each summer over the past six years, global warming has trimmed this ice’s total area a little more, and each winter the ice’s recovery has been a little less robust. These trends alarmed climate scientists, but most thought that sea ice wouldn’t disappear completely in the Arctic summer before 2040 at the earliest.

But this past summer sent scientists scrambling to redo their estimates. Week by week, the National Snow and Ice Data Center in Boulder, Colorado reported the trend: from 2.23 million square miles of ice remaining on August 8 to 1.6 million square miles on September 16, breaking through the previous low of 2.05 million square miles, reached in 2005.

. . . One of the climate’s most important destabilizing feedbacks involves Arctic ice. . . . Melting ice leaves behind open ocean water that has a much lower reflectivity (or albedo) than that of ice. Open ocean water absorbs about 80 percent more solar radiation than sea ice does. And so as the sun warms the ocean, even more ice melts, in a vicious circle. This ice-albedo feedback is one of the main reasons why warming is happening far faster in the high north, where there are vast stretches of sea ice, than anywhere else on Earth.

Homer-Dixon, and many others, believe that these changes foreshadow dramatic and potentially irreversible climatic catastrophe. The ringing of Arctic alarm bells represents a profound shift in global understanding of, and concern for, the Far North. In previous generations, the cold and ice of the Arctic was taken for granted. People knew the North was a forbidding place and understood that human life there was precarious. Few outside the scientific community paid much attention to the idea that there were strong connections between northern conditions and southern climate, or worried much that the environmental changes evident in heavily populated areas might have an effect on the Far North. Indeed, the Arctic was widely celebrated for its pristine nature, for being “untouched” by civilization and industrialization—although environmentalists such as Bill McGibbon, in The End of Nature, recognized decades ago that northern ecosystems were being transformed by global pollution.

Scientists interested in the Arctic have been at the forefront of the global debate about climate change. Given funding, alterations in northern ecosystems are easy to monitor and, because of the relatively uncomplicated nature of the Arctic environment, fairly easy to describe. One of the standard images in the global debate about climate change—useful because it is so simple and so arresting— uses satellite images to document the retreat of the Arctic sea ice. Photographs comparing a surprisingly short period of time reveal a dramatic reduction in the once seemingly eternal polar ice cap. The ice cap used to be called “permanent,” but these images show that it is not. More recent images, drawing on Homer-Dixon’s evidence, show an even more rapid decline in the past few years. In 2006, John Falkingham of the Canadian Ice Service argued that the northern ice pack had shrunk at a rate of 3–4 percent per decade, accelerating to an 8 percent per decade decrease starting in 2000; others suggested a much more rapid decline. By September 2007, Mark Serreze, a senior researcher with the U.S. National Snow and Ice Data Center, declared: “The Arctic is on a fast track of change, and the Arctic sea ice is on a death spiral.”1 Both are moving faster than any of our previous models were telling us. We still don’t understand what’s happening up there.” As scientists look for ways of documenting the extent and speed of climate change, they have found no better and more readily understood symbol of human-induced ecological transformation than in the Arctic Ocean.

Of course, it’s not quite that simple. Much has been made, for example, of the rapid thawing of the Greenland ice sheet along the coast, opening up new areas for settlement and development (as well as potentially drowning Miami). Studies concluded in 2005, however, reveal that the loss of coastal ice was more than offset by additional snowfall at higher elevations. In fact, the total amount of ice and snow on Greenland actually increased, even though the highly visible thawing of ice along the coast suggested a significant decline in the Greenland ice pack. So, is this a bad thing for the world or a good thing? Scientists differ on this question.

Because of its stark beauty, the Arctic lends itself to provocative and attention-grabbing images of nature and the threats posed by global warming. Time magazine’s eye-grabbing cover of April 3, 2006—a polar bear stranded on a small ice floe, seemingly heading off to imminent death due to rapid warming of the Arctic waters— is a perfect illustration of the age and the messaging about the vulnerability of the Arctic. It is a perfect match—the majestic polar bear, the ultimate symbol of the High Arctic, cast adrift by the environmental wickedness of a callous human race. As a graphical illustration of the end of the world—both geographically and metaphorically—it is hard to imagine a more attention-getting image. But it’s also an image of the contradictions of the issue. It turns out that, far from legions of Nanooks drifting off to a dismal death, there are in fact more polar bears in the North than ever. Polar bears routinely live on the edge of the Arctic ice, where hunting is often at its best. They are fine swimmers and move easily between ice floes. But those pictures, however false the impression they may give, sell well at climate change conferences, and Nanook, perhaps happily off eating seal somewhere on the ice, has become the poster bear for global warming, appealing to our fascination with the exotic, our superficial affection for the North, and our need to reduce the scientific complexities of global warming to simple images and slogans.

Most northerners believe that climate change is only too real and they also believe, in the words of Mary Simon, “It’s not about polar bears. It’s about people.”2 The Inuit have no need for scientists to inform them of the major ecological transformations that they are living with. The reduced season for operating ice bridges— crucial means of getting supplies from the south to the diamond mines in the Northwest Territories—is but one example among many of the shifts in northern ecosystems. In 2006, De Beers Canada Corporation reported that warm weather had closed their ice roads for prolonged periods, leaving close to 25 percent of its supplies undelivered during the winter. Indigenous elders talk about changes in ice formation, the migration patterns of animals and birds, and the shortening of winter. While it may seem silly to complain when the North gets warmer, about a few more weeks of summer and fall weather, fewer weeks of –40-degree weather, more vegetation and animal life, northern residents realize that profound changes are under way. The fact that Kuujjuaq, a town in the far north of Quebec, bought air conditioners to help cope with summer temperatures above 30 degrees is certainly a sign of changing times. Traditional knowledge that has supported the region for many generations becomes less reliable when the herds do not show up as expected, when the ice does not freeze as reliably as in the past, and when precipitation levels change.

In some parts of the North, the Arctic thaw has become a matter of life and death. Baba Pederson of Kugluktuk, Nunavut, spoke about insects and birds never before seen in the region, changing ice and sea patterns, and new dangers for Inuit hunters. Speaking about two men from the community who died when their snowmobiles went through the ice, Pederson said, “I blame those deaths on global warming, and that is very scary when it causes people to die.

They were going in an area where they should normally be able to go and everything that they had learned before says it’s safe and it looks safe and they go over it and they drown. That’s scary. All their knowledge didn’t help them.”3 David Ooingoot Kalluk of Resolute Bay worried about global warming, observing that “the snow and ice now melt from the bottom,” making travel much more dangerous than before.4

Because Canada claims so much of the Arctic Ocean, and because the polar ice cap has figured so prominently in Canada’s self-image, the climate change debate has taken on an intensely Canadian focus. It is, after all, Inuit communities in the North that would bear the brunt of major changes in the Arctic climate. In August 2007, the leader of Canada’s New Democratic Party (NDP), Jack Layton, two other NDP MPs, and a left-wing academic from Vancouver toured the Eastern Arctic to meet with northerners and to draw attention to their party’s northern platform. As Layton observed at the end of his Arctic travels,

After years of Liberal inaction and Conservative indifference, Parliament must tackle the growing climate change crisis now. Climate change is threatening the way of life for average northerners and that’s undermining our sovereignty. We can’t protect our sovereignty if we don’t protect our land. As I’ve seen and heard today first-hand, the effects of climate change are a reality for Northern Canadians. We cannot afford to wait.5

Layton heard, as other Canadian politicians have before and after, that there are observable and substantial changes in the North, that the pace of change is accelerating, and that the Inuit and other northern aboriginal peoples will likely bear the brunt of the negative changes. He learned of Arctic communities nervous about the prospect of unstoppable change and the realization that ecological shifts, which are already under way, have the potential to undercut their social and economic system. And because Layton was speaking to the Inuit—an aboriginal population that has a positive international image and that attracts a great deal of global sympathy—he managed to get great press for his venture into the Arctic, as well as make a few pro forma digs at the larger parties.

The Arctic has long held great symbolic importance for Canada and the western world—and it retains its hold on the public’s imagination. Images of stranded polar bears, vulnerable Inuit villages, and despoiled northern landscapes play well with southern audiences. These same images, however, create space and distance from those same audiences. The number of southern Canadians who are going to trade in their SUVs, unplug their air conditioners, or take their bikes out of storage because new insects are making their way into the Arctic or because the harvesting cycles of a small number of Inuit are being disrupted is probably pretty small, though there are more of them every day. Put simply, Pangnirtung does not sell well in Lethbridge or Chatham; if it did, Canadians would have paid attention to the non-climatic crises in northern communities years ago. And if Canadians were truly exercised about threats to the polar bears, we would have had mobs on the streets thirty years ago, when the species did appear truly threatened. However much climate change in the Arctic plays on nationalistic and southern heartstrings, it is unlikely that the unique circumstances of the Far North will be the trigger that convinces Canada and other nations to revisit their emissions standards and to challenge their citizens to accept the drastic reduction in materialism and consumption necessary to address the real challenges of global climate change. Of course, the difference between Inuit children sniffing gas and houses sinking into melting permafrost is that the first problem is a northern one, while the second has implications that affect the south as well, which is the point of the picture of poor stranded Nanook.

The Opening of the Northwest Passage

If the prospect of doomed polar bears, the melting polar ice cap, and severe disruptions to Inuit communities will not galvanize the nation, having more foreign vessels sail through the Northwest Passage may do the trick. When Captain Henry Larsen sailed the St. Roch through the Arctic islands in the 1940s—twenty-eight months going west to east, eighty-six days on the return voyage— he completed an expedition that had long held the world’s imagination. But even for Larsen, travelling during the Second World War, the voyage was more symbolic and exploratory than commercial and substantial. From the days of Martin Frobisher, Henry Hudson, and William Baffin, the world had known of the treachery and danger of the Arctic ice and had long since abandoned the idea of using the Northwest Passage on a regular basis. From the 1960s to the 1990s, the Northwest Passage was a playground for tourists, adventurers, and scientists. There were fascinating questions to be addressed about the movement and depth of the Arctic sea ice, seasonal variations in open water, and the safety of small- and medium-sized craft in northern waters. Only a few people kept thinking of the potential of a shipping route through the Arctic, much more profitable than the route through the Panama Canal, and plotted the commercial use of the Northwest Passage.

How quickly things change in public affairs. In less than a decade, the debate about the Northwest Passage has changed from one of symbolism and sovereignty to one of commercialization and Canada’s ability to protect its northern seas. The reason is climate change and the melting of the polar ice cap. As late as May 2006, scientists forecast that Arctic temperatures would rise slowly over the next century, and safe summertime navigation of the Northwest Passage would be possible by 2070. By the following year, 2007, some observers were suggesting that regular navigation might be possible by 2050. And towards the end of the year, the figure, in a northern version of Moore’s law, had been cut again, to 2030 or earlier. In 2005, the Russians sent an ordinary ship to the North Pole without an icebreaker. Every few months scientists learn more about the pace of global warming and the rapid retreat of the Arctic ice. Passageways deemed all but impenetrable to northern navigation are now ice free for significant portions of the year. Five years ago few predicted that the Passage would be open this soon— twenty years seemed a radical estimate. Though admittedly on the basis of only a few years of data, the possibility of navigating the Northwest Passage regularly, reliably, and soon seems imminent.

Now, of course, Canadians, having paid little more than lip service to the matter for generations, seem keen to protect their northern waters. For years, Canada has not had to act decisively. It has the strongest set of regulations related to its Arctic waters of any Arctic nation, and has permitted zero marine pollution since 1970. But where Norway, Russia, Denmark, and the United States have substantial capacity for Arctic navigation—and where even Australia and New Zealand have substantial capacity for scientific navigation in Antarctic waters—Canada has an aging and underpowered Coast Guard fleet and only a small and scattered naval capacity in the North. In the past few years, submarines from the United States and Russia have been hard at work in the region. More prominently, cruise ships have come there, offering luxury travellers a unique opportunity to explore a part of the world previously available only to the hardiest adventurers. The cruise ships are bellwethers for the future: by making their way through the entire passageway without disaster, they have established the foundation for future commercial use of Arctic waters.

Now, suddenly, after decades of limited control, we are worried about the increased traffic into Canadian territorial waters. We have, for years, maintained that the Northwest Passage is part of our internal waters and not, as the Americans and others claim, a strait used for international navigation that must be available to all, like the Straits of Gibraltar and other critical passages. The UN Convention on the Law of the Sea spells out internationally accepted practices in such areas,6 but the rapidity of climate change in the North has forestalled the standard Canadian response, which is usually to protest loudly and to announce impending plans to build naval capacity for the North that die on the order paper before the next election. National politicians know very well that Canadian interest in Arctic sovereignty issues is shorter than an Arctic heat wave—rarely outlasting the voyage of the offending foreign vessel—and that there are few, if any, consequences from backing away from commitments to protecting the North from future intrusions. Furthermore, such concern is limited to academics and political groupies. But the “announce northern infrastructure and then forget it” approach is woefully inadequate in the present situation, for development pressures on the Arctic are increasing steadily with little prospect of an end to demands for an open Arctic waterway.

CGS Henry Larsen sails alongside HMCS Goose Bay during Operation “Lancaster,” August 2006. Prime Minister Harper declared that Canada’s territorial integrity “takes a Canadian presence on the ground, in the air and on the sea and a government that is internationally recognized for delivering on its commitments.” DND photo AS2006-0515

The prospect of regular navigation of the Northwest Passage has generated a great deal of debate. There’s huge money at stake. The Tokyo-London journey would be shortened from 20,930 kilometres (13,000 miles) via the Suez Canal or more than 22,540 kilometres (14,000 miles) by way of the Panama Canal to only 16,100 kilometres (10,000 miles) if the Passage stays open. This highlights the fact that not all effects of global warming are bad— think of the fuel saved when voyages are reduced by 40 percent. There is also a risk substitution issue at stake in the Northwest Passage debate. The rapid growth of the Asian economy has sent shipping traffic through the Malacca and Singapore Straits skyrocketing, with the number of transits expected to grow from 70,000 in 2007 to 140,000 in 2020.7 The opening of the Northwest Passage would reduce traffic in this overcrowded waterway, thus limiting environmental risk in the area. Some businesspeople applauded the commercial opportunities that would attend shipping to the North, and the resulting stabilization of the northern economy. Scott Borgerson of the U.S. Coast Guard Academy highlighted the positive aspects of global warming, particularly the prospect that the Arctic Ocean could “become the common body of water linking the world’s most important economies, all of which are located in the northern hemisphere.”8 For analysts like Borgerson, the opening of Arctic waters could easily match the construction of the Suez and Panama Canals in terms of the impact on global shipping and international trade, requiring only a suitable legislative and regulatory regime to protect national and security interests.

Other observers are worried about the potential environmental dangers—the sinking of a full-laden ship in the Arctic could cause severe ecological damage—particularly since, given the severity of Arctic storms, there’s no assurance that the waterways would prove reliable and safe. Moreover, the prospect of dozens, if not hundreds, of foreign-flagged vessels in Arctic waters each year raises a variety of security and defence issues that Canada is ill prepared to address. The prospect of a wide-open Arctic passageway was, of course, a logical extension of the long-standing American belief in freedom of navigation for its navy. America’s position that Canadian permission was not required to sail through the Arctic means that any “North Korean or Chinese ships [can] sail through North American waters without asking anyone’s permission. From a national security perspective, that’s a mad policy,” commented Rob Huebert of the University of Calgary. Furthermore, he added, the fact that Canada did not require ships to seek permission to enter the area made little sense: “It’s like asking speeders on a highway to report themselves.”9 For a smaller number of commentators, led by Huebert and UBC academic Michael Byers, the opening of the Northwest Passage also creates major security concerns. As Byers noted in January 2006, the creation of a major international shipping route could mean there was a “backdoor to North America that is wide open.”10

Most observers paid little heed to such comments, which asserted that northern tankers would make an attractive target for terrorists. The suggestion that Al-Qaeda operatives, drug smugglers, illegal immigrants, or other miscreants would enter North America from the High Arctic struck many observers as far-fetched, although caution about underestimating the determination of America’s opponents gave some credence to Byers’s observations. Paul Cellucci, former U.S. ambassador to Canada, urged Canada to adopt more of a military presence in the Arctic: “That would enable the Canadian navy to intercept and board vessels in the Northwest Passage to make sure they’re not trying to bring weapons of mass destruction into North America.”11 The more general warning about the opening of the waterway—that retreating ice would result in the testing of Canadian sovereignty and would likely show Canada’s capacity in the North to be seriously wanting—struck a stronger chord: “I don’t want Canadian policy to be decided on the fly,” Byers observed, “under a timeline that’s been set by some ship that’s registered in Panama or Liberia with a Filipino crew.”12

Many are inappropriately uncomfortable with the prospects of an open race to capitalize on the open waters of the Arctic. The Arctic Monitoring and Assessment Programme (AMAP) provides widely shared information on the state of the Arctic ice cap. Organizations like the Arctic Council and the Arctic Marine Shipping Assessment (AMSA) group call for unified research, monitoring, and self-regulation, in an effort to head off conflict and potential environmental catastrophes. The search for standards for Arctic shipping attracted interest from such diverse groups as the Russian Register, Lloyd’s Register, and the American Bureau of Shipping, with considerable agreement that collaboration on ship design, crew training, insurance, and the use of Arctic passageways was in order.13

Not everyone is going to lose if northern waters get warmer, though. So much attention has focused on the opening of the Northwest Passage that there has been little comment on some of the other consequences of global warming. Consider, for example, the long-neglected port of Churchill, Manitoba. Opened in 1931 and intended to capitalize on the global demand for prairie wheat, the port was long plagued by the short season and difficult navigation in Hudson Bay. For decades the port limped along, underutilized, dashing hopes for a central North outlet to Europe, leaving the community to survive on polar bear tourism. In 1997, the government of Canada gave up on the port, selling the facility to an American entrepreneur, Pat Broe, and OmniTRAX for a measly seven dollars.14 Broe’s investment may prove to be a brilliant one. The further opening of Hudson Bay navigation will lengthen the shipping season, reduce the hazardous ice buildup in the bay and the often treacherous Hudson Strait, and convert the Port of Churchill into a going concern. Even the Russians are getting into the act, with Igor Levitin, Russian transport minister, offering to use icebreakers to keep Churchill open year-round, mirroring the aggressive Russian strategy of investing heavily in the Murmansk port facility to improve access to international markets. By shipping directly from the two northern ports—Murmansk to Churchill—ships could reduce the trip from Russia to North America from seventeen to eight days, revolutionizing ocean navigation and transportation across the Arctic waters. In the Western Arctic, the retreating ice cap will make the Beaufort Sea oil and gas wells easier and less risky to develop, and improve access to the fields, particularly for tankers supplying the burgeoning Asian market.

While political pronouncements garnered national attention, a small but highly symbolic event occurred at Churchill on October 17, 2007. The same day that Prime Minister Harper’s government made bold statements about national commitments to the North, the Kapital Sviridov, a ship owned by Murmansk Shipping Company, arrived in Churchill. The Kapital Sviridov carried a load of fertilizer destined for the Canadian prairies. Using the “Arctic Bridge” route for the first time, the Russian vessel delivered its cargo at close to 10 percent less cost than the traditional southern Canadian option. Churchill mayor Mike Spence declared optimistically that the Kapital Sviridov was but the first of many ships that would capitalize on the retreating Arctic ice. Its arrival at Churchill provided one of the first and most tangible signs that, perhaps, a new North was emerging from under the retreating ice.

Arctic Resources: The New Imperative

In 1576, when Martin Frobisher first reached Baffin Island, he discovered impressive quantities of gold ready for easy collection. The gold turned out to be iron pyrites, and Frobisher ended up in disgrace because of his involvement with what his British countrymen saw as a massive fraud. Since the sixteenth century, the Arctic has become synonymous with a curious northern mix of overinflated expectations regarding resources and disappointment surrounding the reality of northern wealth. And so, through the post–Second World War era, there have been tentative but substantially unrealized efforts to develop Arctic resources. With a short-term but prosperous mine here and there, like Polaris and Nanisivik, promising oil fields in the Beaufort Sea and some meagre petroleum finds at Melville Island, the Canadian Arctic seemed destined to fulfill a pattern of glimmers of hope followed by crushing disappointments.

For decades, the Arctic presented a wide array of technological and climatic barriers to resource development. Thick ocean ice, difficulties with transportation, and high energy costs and wages were compounded by the lack of solid scientific data on the vast expanse of the region. But a conjunction of twenty-first-century developments has changed the equation with surprising speed. The rapid increase in resource prices has made once-marginal fields and properties commercially viable. Expanded scientific research and enhanced technologies have made it possible to define promising opportunities more precisely. The threat of shortages in southern areas, combined with the realization of the astonishingly huge untapped potential of the Far North, has given a sharp edge to the issue. The U.S. Geological Survey (USGS) originally estimated that the region holds up to 25 percent of the world’s undeveloped oil and gas reserves—although the USGS has since retracted this estimate and is undertaking further studies. Helge Lund of Statoil, the state oil company of Norway, has estimated the Arctic basin resources at 375 billion barrels, saying “It will never replace the Middle East but it has the potential to be a good supplement.”15 Manoucheher Takin of the Centre for Global Energy Studies in London is more optimistic, claiming that there could be between 50 and 100 million barrels of easily extractable oil and gas, accessible within a decade.16 An assessment by energy consulting company Wood Mackenzie in 2007 put the figure at 20 percent of the world’s reserves, most of it natural gas and most of that, almost 70 percent, within Russian control. Add to this improved communications, growing sophistication in the development of fly-in mining camps and removable mining facilities, better search-and-rescue capabilities, and Arctic projects suddenly became commercially and logistically possible. Of course, climate change has expanded the exploration season, opened shipping lanes for longer periods of time, and reduced the costs of operation due to reductions in cold weather and snow and ice. As British commentator Carl Mortished noted about developing the resources, “The physical danger is great and the cost gigantic, with $1 trillion a low ball estimate to recover the resource . . . But whatever the price, the oil majors must push north. The door to the Middle East is shut, biofuels pose a threat to food production and coal is dirty. If Shell, BP and ExxonMobil are to remain open for business, the Arctic is the only frontier left.”17

The northern resource rush, however, looks like none other in Arctic history. The Russians, ascendant in the North and looking for opportunities to enhance their economy, have increased their exploration activities, including along the seabed. American firms, aware that the Prudhoe Bay oil fields are running low, have eyed northern resources and the uncertain northern boundaries with growing interest. The traditional image of the lone wolf prospector—like Stuart Blusson and his partner, Chuck Fipke, who discovered diamonds in the Northwest Territories and founded the Ekati Mine—is giving way in the High Arctic to highly sophisticated multimillion-dollar exploratory teams, using satellite and other technologies to identify promising possibilities. Much of the work to date has been preparatory in nature, as oil and gas companies gear up for the gradual opening of the Arctic Ocean for full-scale exploration and development. There will be intense scrutiny of the environmental aspects of Arctic resource development, but most of the rich fields are a long way from the nearest indigenous settlement, so there should be none of the difficulties that have delayed the Mackenzie Valley Pipeline for over thirty years now.

Arctic resource potential can be readily seen in Hammerfest, a hitherto small outpost at the far north end of Norway that, remarkably for the North, achieved formal town status in 1789 and was the first in Europe with electric street lighting, in 1891. The construction of the Snohvit (Snow White) project, a close to $9 billion processing centre for liquefied natural gas, has drawn thousands of workers to the area. Snohvit, however, is intended to be the start, not the end, of Norway’s Arctic oil and gas exploration activities, with hopes running high that explorations in the Barents Sea and farther north than Spitsbergen will uncover additional oil deposits. The combined Russian-Norwegian undersea Arctic play, designed to produce gas for exports to the American Northeast, is the largest and more promising of the northern resource initiatives. Hammer-fest consultant Arvid Jensen noted, “Oil will bring a big geopolitical focus. It is a driving force in the Arctic.”18

Hammerfest is not likely to remain the only Arctic hot spot. Russia’s Yamal Peninsula holds an estimated 480 trillion cubic feet of natural gas, attracting the attention of companies like Repsol of Spain despite the formidable logistical challenges of operating in the Far North. Seasoned veterans cautioned against unrealistic expectations: “It will ‘feel great’ as the winters warm for the next YPF 20 years and we start tapping the reserves in the Arctic. But it will still cost $100 to $150 a barrel for it. The ice may be gone—but the Arctic is a harsh environment—and a long distance from where the markets are.”19

If this sounds like a booster advertisement for the happy side of global warming, consider the following vicious circle of events:

Greenhouse gas makes the climate warmer.

Warmer climate melts Arctic ice.

Less Arctic ice means that it’s easier to find and extract more oil and gas.

More oil and gas burned means more greenhouse gas, and so on . . .

The Arctic has more than oil and gas on offer. In the summer of 2006, Prime Minister Stephen Harper joined an impressive array of bankers, mining executives, and others for the opening of Tahera Diamond Corporation’s new Jericho Mine in Nunavut. Harper was roundly criticized for skipping an international conference on AIDS/HIV to attend the mine opening, but as one executive noted, “If he went to the conference, it would do nothing to speed up a cure for AIDS. [B]y coming here and announcing that the north is open for development, [Harper] will bring investment dollars to this part of the world.”20 The development of yet another diamond mine, with another opening in 2007 and other properties under consideration, fuelled southern investment in the North and generated near–Klondike-like enthusiasm for the Far North. Significantly, what set the new projects apart from their post–Second World War predecessors is that northern indigenous peoples played a significant role in the planning and operation of the mines.

It turns out that there is more than oil and gas under the Arctic ice, although the other resources have not yet attracted as much attention as the prospect of oil rigs and tankers working their way through the region. Preliminary investigations suggest that there are marketable mineral deposits and potentially coal on the Arctic seabed, though of course there’s no shortage of coal easily accessible on dry land; furthermore, it’s the worst possible fuel to burn from a global warming perspective. Moreover, the Arctic fisheries have barely been touched, raising the possibility of a major surge in activity in this area as well. Graham Shimmield, of the Dun-staffnage Marine Research Station in Scotland, and a leading scientist in the field, worries about the potential rush to exploit the hitherto untapped fishery: “There is strong evidence that there are still good reserves of fish such as cod and capelin in some regions of the Arctic. However, these are probably the world’s last refuges. We should restrain ourselves from catching them on an industrial scale until we learn more about how strong they are.”21 The signalling of major fish stocks in a largely unregulated ocean is likely to spark a rush into the Arctic as soon as ocean navigation becomes reliable.

A long-standing joke about the Canadian Arctic is that the average Inuit family consists of a man, a woman, their children, and an anthropologist. According to Guy d’Argencourt of the Nunavut Research Institute, the demographics have changed. The anthropologists have been replaced by geologists!22 The Arctic has long been an area of promise and hidden potential. True, developable properties are few in number and widely scattered, and the prospects for finding substantial quantities of oil and gas in the region remain a matter of hope and conjecture. But with the world rapidly running out of known and potential gas reserves, hope springs eternal that the discovery and development of Arctic resources will postpone the day of energy reckoning for several additional years. There is the possibility, as well, that the Arctic seabed has a series of what are called “hot smokers, super-heated water jets containing valuable minerals such as manganese, platinum and gold.”23

Rachel Qitsualik, an Inuit writer, offered a sarcastic commentary for those who assumed that the euphoria of the early twenty-first century would produce great wealth and opportunity. Writing from the imaginary perspective of 2020, she described the milita-rization of the North and major increases in sea mammal populations due to global warming, and then described a series of dashed dreams and unexpected twists: “It’s amazing to think back on all the saber-rattling between the United States, Denmark and Canada over rights to the Northwest Passage only to have so many ships ripped apart by unanticipated icebergs. In 2018 there was much hoopla over Canada’s new U.S. friendly licensing system for foreign usage of Canadian Arctic waters, even though America had already been using the waters since 2009. The issue only came to the forefront of public awareness in 2011, when [the Rose of Texas] an American oil tanker, was split open 300 kilometres from Gjoa Haven, ruining local fish stocks and poisoning coastlines.” She continued in a similar vein, describing the resource-inspired boom, abandoned mine and townsites, and writing, “As they retreated to the South again, pockets empty and with bittersweet memories of a beautiful but strangely unprofitable land, they were haunted by a single, frustrating mystery: the knowledge that they could never say exactly why the Arctic hadn’t been what they’d expected.”

Qitsualik offered a perspective on the northern resource boom rarely heard in Canada: “The truth is that the Arctic is warming— but I fear more for how the South will react to it than I do for Inuit.” The Inuit know, she said, that the Arctic is a harsh and unforgiving land, that the southerners’ visions of northern prosperity rarely come true, and the Inuit will remain long after the newcomers flee, with Arctic wealth or impoverished by unrealistic dreams. Casting her thoughts back over thousands of years of Arctic history, which included other periods of Arctic warming and cooling, she believed her people would adapt once again: “And they will adapt, even as they whisper a prayer over the skeletons of those who refused to do the same. For Inuit have never owned The Land, having learned of old that it is no man’s resource.”24

Canadians woke up to the new Arctic realities when anxious commentators declared that the hitherto benign Danes, marketers of teak furniture and fairy tales, had dared to lay claim to Hans Island, suddenly a crucial piece of Canadian territory. The contested ownership of this barren rock, lying almost exactly mid-channel between Greenland and Ellesmere Island, had actually come to light in 1972 when Canada and Denmark met to negotiate an agreement to delimit their respective continental shelves. Rather than getting hung up on this minor matter, the treaty negotiators simply left 875 metres (0.54 miles) of border in Nares Strait unsettled and concluded the longest shelf-boundary treaty negotiated to that time: a whopping 1500 kilometres (932 miles).25 While Canada had done more to exercise sovereignty over the remote island than its northern neighbour, the Danes have not renounced their claim. This did not raise the spectre of sovereignty loss, however, and discussions with Denmark on the issue were marked by a notable lack of urgency. Far from fighting over the barren island, the countries collaborated on the management of the local environment. The realization that a Canadian company, Dome Petroleum, was using the island as a research base sparked a classic Arctic-sovereignty reprisal by the Danes—they flew by helicopter to the island in 1984 and deposited a flag, a bottle of schnapps, and a note: “Welcome to the Danish Island.”26 So there, Canada! Scarcely a handful of Canadians had heard of Hans Island before 2004, but in that year, Canada’s ability to hold on to this tiny and isolated piece of windswept rock in Nares Strait became a test of national will and commitment to the North.

Colonel Norm Couturier, Commander of Canadian Forces Northern Area, briefs the media on details of Operation “Kigliqaqvik IV,” a long-range sovereignty patrol on and around Ellef Ringes Island in Nunavut, April 2005. DND photo IS2005-0039

And then things got a little silly. Starting in 2004, the Canadian media began running stories about Danish designs on the tiny chunk of contested rock, claiming that Canada had neglected its northern territory and that the Danes were moving in. The opposition Conservatives assailed the governing Liberal Party for their inability to defend the Arctic islands properly. The rhetoric inflated very quickly. Claims circulated that Canadian military exercises in the area were in response to Danish actions—they were not—and rumours circulated that the Danes had plans to move into the area. Canada’s minister of national defence, Bill Graham, visited the island in July 2005, followed quickly by a formal Danish complaint about Canadian incursions on Denmark’s territory. Further research concluded, appropriately given the slapstick nature of the “conflict” over Hans Island, that the island was neither Canadian nor Danish but probably belonged to both countries. The issue remains unresolved, with both countries still claiming sovereignty over the tiny piece of Arctic nothingness.

Canada, it must be noted, seems particularly drawn to conflicts with minor European powers, perhaps because we have too much sense to get into fights with bigger ones. In a 1994 controversy over fishing off Newfoundland, Fisheries Minister Brian Tobin actually ordered Coast Guard vessels to shoot over the bows of Spanish ships, arresting several and having them towed to harbour for impounding. The Hans Island affair fitted nicely with this pattern of Canadian sabre-rattling—a strong position over a seemingly inconsequential matter with a non-military rival whose own engagement on the issue was also haphazard. Few Canadians would have anticipated in 2005 that the minor squabble over Hans Island would be the opening salvo in a rapidly expanding conflict over the control of the Arctic.

Boundaries are assumed to be immutable. With a handful of exceptions—Kashmir between India and Pakistan, Somalia and several other failed African states—the lines drawn mostly in the nineteenth century have come to define the geopolitical outlines of the world. Funny, then, that the latest debate over the cartographic outline of the world would take place in two of the unlikeliest places in the world: underwater and in the High Arctic. Steve Gregory of Weather InSite commented in 2006 that “it’s becoming more and more obvious that we’ll be able to do drilling in the Arctic 161 to 322 kilometres (100 to 200 miles) off the coast, year-round. It used to be no one cared about borders and ownership up there, but now this leads to new problems, political fights. All the countries bordering the Arctic now care who controls particular areas and how do you draw those lines.”27

The United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea allows states to exercise exclusive jurisdiction over the resources on and under its extended continental shelf—the underwater extension of the landmass. (The technical wording is a “natural prolongation” of the continental shelf.) The recognition of the importance of the continental shelf through the creation of the EEZ had earlier allowed Canada to assert control over the fishery off the Grand Banks of Newfoundland, permitted Iceland to maintain effective management of its offshore fishery, and generally redefined the zone of national responsibilities around all maritime nations. Little public attention had been paid to the Arctic, primarily because of the doubtful value of underwater holdings trapped below many metres of solid ice, leaving the precise boundaries of the continental shelf in the Arctic undefined and hence unsettled. In fact, Canada has not yet completed the scientific research to delimit any of its shelf in the Arctic or in the Maritimes. The Convention gives us ten years from when we became a party to it, which happened in 2003. What is more, the complex underwater Arctic topography creates a formidable scientific challenge, as Richard Scott, a Cambridge University scientist observed: “The difficulty we have in the Arctic Ocean is that there are a lot of ridges and it is not clear whether they are attached to the continental shelves. The necessary data is missing at the moment. We have some information, but not very good information.” And getting that data was no easy feat, as Andrew Latham, a British energy consultant, commented: “The technology to even explore in that sort of location is fledgling to put it mildly. If you’ve got to run icebreakers just to do a seismic survey, then you are into horrendous costs.”28

In the summer of 2007 the public debate changed dramatically. In June, the Russians claimed that they had identified the precise nature of the Lomonosov Ridge, the underwater mountain range that rises some 3,500 metres (11,475 feet) from the ocean bed and runs between Ellesmere Island and Siberia. More dramatically, the Russians claimed that their discoveries documented the extension of the continental shelf in the Arctic. Eventually, they will make a submission to the UN Commission to assert their right to the resources within 1.2 million square kilometres (0.46 million square miles) of Arctic seabed. (Canada’s claimed area may amount to as much as 1.75 million square kilometres [0.68 million square miles].) Political scientist Michael Byers reacted to the news with alarm: “The stakes are simply too high and time is running out.” While some Canadian scientists described the announcements as “premature,” David Hik, of the University of Alberta, advised Canadians to take the Russian scientists seriously, noting that they have a “very credible history of scientific research in the North. We have to remember that almost half of the Arctic is in Russia.”29

A July expedition raised the symbolic stakes to the highest point yet. Reports surfaced that Russian scientists, working off the Akademik Fyodorov, the country’s most important research vessel, and accompanied by the icebreaker Rossiya, would use submarines and cutting-edge technologies to descend to the seabed directly at the North Pole. The expedition, led by Arctic scientist Artur Chilingarov, himself a politician and Hero of the Soviet Union, included two representatives from the Russian Duma and sought, in the words of politician Vladimir Gruzdev, to “remind the whole world that Russia is a great polar and scientific power.”30 Chilin-garov was more assertive: “The Arctic is ours and we should demonstrate our presence.”31 He declared that the expedition ranked among the greatest of all human feats of exploration: “We face the most severe and risky task, to descend to the depths, to the seabed, in the harshest of oceans, where no one has been before and to stand in the centre of the ocean on our own feet. Humanity has long dreamt of this.”32 The hyperbole suited the overheated rhetoric of the modern Arctic, for of all the world’s great geographical challenges, this one had probably fuelled more fantasies than any other. The Russians played the exploration metaphors to the point of excess, likening the descent to the first step on the moon—and even linking the submariners with Russians in outer space. The descent went as planned, using submersibles MIR 1 and MIR 2 to check out the seabed some 1300 metres (0.8 miles) below the surface. The scientists deposited a Russian flag, encased in a titanium container, on the sea floor, bragging that evidence of the Russian presence would be around for hundreds of years. Chilingarov and his team were treated to a hero’s welcome when they returned to Russia, a striking sign of the intersection of nationalism, science, and the Arctic in modern Russia.

Closer examination revealed some odd elements in the Russian expedition. The lustre of their accomplishment was tarnished subsequently when it was revealed that the television footage used by Russia to document the journey actually came from the movie Titanic. Furthermore, foreign businessmen Fredrik Paulsen of Sweden and Michael McDowell of Australia had paid upwards of $3 million for the privilege of joining the Chilingarov project.33 Indeed, despite the inflated rhetoric of the summer of 2007, international co-operation and the mingling of business, science and sovereignty seemed to be the order of the day. Almost all of the expeditions launched to explore the seabed involved more than one country—an oddity in the so-called race to the Arctic ocean floor.

However, the Russian activities did grab Canada’s attention. Foreign Affairs officials declared that the country’s sovereignty was long-standing, well established and based on historic title. As for continental shelf extension, Canada was just in the process of conducting its science. All submissions are subject to review and counter-evidence, which was being collected by Canadian and Danish scientists (a co-operative endeavour that showed how much Canada was getting along with Denmark, despite all the hoopla over Hans Island). For some observers, Canada was best served by falling back on its informal arrangements with the United States. Michael Byers argued that Canada and the United States should finally resolve the boundary line in the Beaufort Sea, collaborate on scientific research, and support each other’s claims to the Commission on the Limits of the Continental Shelf, created under the UN Convention on the Law of the Sea. Favouring a combination of a “serious investment of money and personnel as well as imaginative and proactive diplomacy,” Byers questions: “Is Canada a serious Arctic country? Are we in this race to win?”34

While Canadians dismissed the Russian activities as hollow symbolism and rejected the argument that Canada’s sovereignty over the region had been diminished, the reality was that Russia had taken a huge leap forward. Canada lacked both the icebreakers and submarines necessary to match Russia’s feat and was years away from having the capacity even to monitor the Arctic properly, never mind do anything there. Joe MacInnis, a Canadian diver with long-standing interest in the Arctic, described the Russian manoeuvre as “the world’s wildest land claim” and noted, “I’ve always taken the position that it’s one thing to claim sovereignty. It’s another thing to be able to go to the place that you claim. The Russians at least have got a sub that takes them to the bottom, that’s the place that they’re claiming.”35 MacInnis had participated in a Canadian expedition to the North Pole in 1974 where he swam under the ice and left a Canadian flag underwater. He returned in 1979, this time surveying the Lomonosov Ridge. He was not impressed with the Russian effort: “In the high Arctic Ocean, the rules of the land do not apply. The six months of sunless winter skies, the grinding ice, the fearsome winds, the freezing depths and the remote seafloor make this a place where sovereignty has a different meaning from sovereignty on land.”36

Peter MacKay, Canada’s foreign affairs minister, reacted angrily to the Russian manoeuvre: “This isn’t the 15th century. You can’t go around the world and just plant flags and say, ‘We’re claiming this territory.’”37 MacKay’s confident assertions tried to allay serious questions inside the country about the security of Canada’s claims to the Arctic, and he was definitive: “The question of Arctic sovereignty is not a question. It’s clear. It’s our country. It’s our water. It’s the ‘True North strong and free’ and they are fooling themselves if they think dropping a flag on the ocean floor is going to change anything.” The U.S. State Department dropped the bluster in favour of sarcasm: “I’m not sure of whether they’ve put a metal flag, a rubber flag or a bedsheet on the ocean floor” scoffed a spokesman.38 The Danes dismissed the Russians’ actions as a media stunt, an opinion, interestingly, that appeared to be shared by Russian scientists exploring the ocean floor. As the Daily Telegraph observed, “Mr. Chilingarov’s stunt was a provocative but humorous challenge. Canada and the United States spectacularly rose to the bait.”39 So did much of the world’s media, including The Independent (London), which devoted the front page to the story and greeted the descent with a large headline on July 31, 2007: “The North Pole A New Imperial Battleground.” But this is more serious than scoffers think. Of course it was a stunt. Stunts make news and set precedents. Was it less of a stunt than the various attempts at the Passage in the nineteenth century, the hunt for the source of the Nile, or the race to the North and South Poles? Sovereignty claims can grow from the seeds of such stunts.

The contest—portrayed in the press and the political arena as a race to the Pole—is really nothing of the sort. In truth, Canada’s claim on Arctic lands and maritime areas is as solid as international law provides. There is no question about Canadian ownership: neither Canadian lands nor our maritime area are in question. No foreign state claims them, with the exceptions of Hans Island and parts of the Beaufort and Lincoln Seas. Delimiting our extended continental shelf will take place according to international rules which all countries are respecting. Of course this means that Canada will have to negotiate on its northern boundary issues, just like hundreds of boundaries still being negotiated around the world. But the bottom line is that Canada’s ownership of its Arctic Archipelago and the water within it is without question.

Canada’s adoption of the UN Convention on the Law of the Sea set out a new time frame and process for recognizing control of its extended continental shelf. Countries have ten years from the point of adoption to make their submissions. Canada ratified the Convention in 2003, so the country has until 2013 to assemble its case, which will be placed before a non-partisan panel of scientists for adjudication. Signatories to the deal further agreed that claimants could bring forward evidence that documented the actual nature of the continental shelf. The research would be evaluated and, if a country’s case was scientifically proven, the claim to the extension of the continental shelf would be accepted and the national boundary expanded accordingly. Five countries—Canada, Russia, Denmark, the United States, and Norway—all have Arctic claims, although the United States is not a signatory to the Convention and therefore is not bound by the process. (Iceland, although generally viewed as an Arctic nation, is not deemed to have any northward claims on the Arctic seabed.) The 2007 debate about Russian claims to the Arctic altered American positions on the Law of the Sea and appears likely to result in the United States signing on to the accord, largely to ensure that the country has a means of securing its interests in the Western Arctic.

The Arctic countries have all started to survey the Arctic seabed to determine where their shelves reach. Norway has already made its submission. Russia is also very active, which is understandable because its new deadline expires in 2009. The United States also has made substantial research commitments in the High Arctic, despite not yet being a party to the Convention. Canada has also been active in the lead-up to our submission in 2013. The Russian government took a large step forward in 2006–7 when submarine explorations allowed it to demarcate the outer edges of the continental shelf in the Arctic. Media commentators in other nations with interests in the area, such as Denmark, Canada, and the United States, resented what they construed as Russia’s intrusion. But the bottom line is that Canada’s ownership of its Arctic Archipelago and the water within it is without question.

In truth, Russia made its claims in accordance with applicable rules, though the Commission on the Limits of the Continental Shelf did not approve its application as presented.40 To back their claim, the Danes added millions of dollars to the funds devoted to surveying the ocean floor.41 Canada has done the same. New scientific expeditions were launched to provide surveys of the polar seas, partially as a matter of national pride, but also to defend potential economic interests to the oil, gas, and mineral resources that might be found underwater. In February 2008, Andy Armstrong, an official with the American National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, announced a “big discovery” concerning the sea floor off the coast of Alaska—the sea floor stretched more than 100 nautical miles (115 statute miles) farther out than had previously been thought—and commented that Canada and the United States were on a “collision course” over Arctic Ocean. seabed rights in the Arctic Ocean.42

In March and April 2008, scientists and members of the Canadian Forces conducted research on the Ellesmere Island ice shelves. DND photo IS2008-3984

As debate rages on the ownership of the seabed, some commentators suggest that Canada’s claim is far from secure. Rosemary Rayfuse, of the University of New South Wales, Australia, offered a cautionary comment: “As a matter of legal principle, Canada has no greater claim on the Arctic than any of the other . . . Arctic states, or indeed any state in the world, quite frankly. Depending on the geological realities, Canada may have a geological claim on some extension of the continental shelf, although I think that Russia and Norway have the greatest amount, from what I’ve seen.”43

Who would have thought five years ago that the world would be squabbling over the undersea Lomonosov Ridge and that Canada, Denmark, Russia, and the United States would be jockeying for stature in the Far North? Perhaps lawyers who read the Law of the Sea, which explains the rights of coastal states to their continental shelf,44 or foreign policy specialists who acknowledge that states can have conflicting interpretations on boundaries, have their facts right. But the debate is important for a number of reasons, not least the fact that it has important security overtones. The British, anxious to assert their military presence, have run submarines under the Arctic ice since the mid-1980s, and they knew that the Russians were re-establishing their submarine capacity and extending operations in the region. The Arctic debates, surprisingly, alerted countries with Antarctic claims and responsibilities to the possibility of commercial and other opportunities there as well. By the fall of 2007, Britain was asserting continental shelf claims to a vast area of the southern seas, sparking an angry response from the Argentinians and likely signalling the start of a southern undersea land rush paralleling the Arctic furor. There are, however, fundamental differences between the two polar regions: “The South Pole is an expensive place to exploit and it was realized that if everyone agreed not to touch it, they could all rest easy about pouring millions into the area. This is not the issue with the Arctic. It is becoming easier and easier to exploit. Nations aren’t going to give up on these rich pickings.”45 Suggestions that the Antarctic model—governing the region through an international agreement that controlled development and protected the environment—be applied in the North have attracted little support.

Largely missing in the debate over the Arctic is the global nature of the continental shelf controversy. The UN Convention, often cited as stimulating the latest race to the North Pole, has wide international implications, for countries from Russia to Australia, Brazil to Australia have already made their claims to continental shelves, with many others soon to follow. As Scandinavian scientist Lars Kullerud observed, “This will probably be the last big shift in ownership of territory in the history of the earth,” with total claims exceeding the size of Australia. Yannick Beaudoin, a colleague of Kullerud’s at GRID-Arendal Foundation, noted, “Many countries don’t realize how serious it is. 2009 is a final and binding deadline. This allows you to secure sovereignty without having to fight for it.”46 Only Russia has a 2009 deadline in the Arctic, but many commentators are playing up the need for urgent action by other circumpolar states, preying upon fears that they will lose out in “this great Arctic gold rush.”47 While media attention focused for a time on the Arctic, subsequent disputes in hotly contested areas like the South China Sea, Easter Island, and Madagascar have the potential to make the Law of the Sea a hot topic in the coming decade.

Article 77 of the UN Convention explains that coastal states already have sovereign rights over their continental shelf in terms of exploration and exploitation of natural resources, regardless of occupation or “any express proclamation,” but this does not give pessimists much comfort. Other commentators, such as Hans Corell, who was responsible for supervising Law of the Sea matters at the United Nations, are less sensationalist. “The United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea is the comprehensive multilateral regime that applies in the Arctic,” Corell observes, and “there is nothing to suggest otherwise. As far as the rights of coastal states are concerned, the convention distinguishes between territorial sea, the exclusive economic zone [EEZ] and the continental shelf. Apart from the territorial sea, which extends 12 nautical miles (13.8 statute miles) from the baselines, the questions that arise in the Arctic are definitely not about territory over which states have sovereignty.” Although states have the right to exploit the resources in or on the seabed itself in their exclusive economic zones or on their continental shelf, they do not have a legal right to control the freedom of navigation on the high seas. Sea areas in the Arctic that lie beyond the exclusive economic zones and continental shelf of circumpolar states “are referred to in the Convention as the common heritage of mankind. There are clear provisions to the effect that no state shall claim or exercise sovereignty or sovereign rights over any part of this area or its resources.” In Corell’s view, ideas that competing powers are “racing to carve up the region” which could “erupt in an armed mad dash for its resources” are “not only misleading” but “utterly irresponsible.”48

Why is it, then, that Canadians are so concerned about losing their Arctic inheritance? Canada has relied so long on the assumption that the 141st meridian that divides the Yukon and Alaska simply extends to the North Pole that it has prepared minimally— psychologically and militarily at least—for any challenge to its sovereignty in the area. As earlier chapters revealed, Canada reacted to various sovereignty and security crises during the Cold War out of fear that our circumpolar neighbours threatened our national interests. Because Canada has generally neglected the region in terms of development and defence, focusing on southern Canadian priorities whenever it could, this meant that any perceived encroachment was bound to trigger a reaction. Often these anticipated “threats” reflected our inability to acknowledge that our Arctic counterparts also had interests, and that we’d have to negotiate with them when those interests conflicted with ours. The current debate, it seems, is based on similar confusion. Canadians have interests, as do our neighbours, but we’re worried that we’re falling behind in a “race” to protect ours. The debate has practical issues as well. Neither Canada nor the United States has the scientific capacity to match current Russian investigations of the Arctic. The possibility remains that if the Russians are as prepared and determined as their actions to date suggest, they will move unilaterally into the area and will test the old adage that possession is nine points of the law.

A Globe and Mail report on the status of Canadian capacity in the Arctic, published in October 2007, revealed the puny nature of Canada’s military presence in the Far North. A map of land-based defences shows a tiny base at Resolute Bay, a small camp for the cadets and Junior Canadian Rangers in Whitehorse, and the Joint Task Force North headquarters in Yellowknife. The map also identified all of the RCMP stations in the North, most of them with only a handful of officers on station. Aerial defences included a substantial advanced radar detection system, major bases in the south (Cold Lake, North Bay, and Bagotville) with northern responsibilities and a series of Forward Operating bases, to be used in times of emergencies, at Yellowknife, Rankin Inlet, Kuujjuaq, and Goose Bay. Canada’s Arctic naval capabilities, most depressingly, consist of ships stationed at Esquimault, near Victoria, B.C., and Halifax, Nova Scotia—plus a proposed Arctic deep-water port at Nanisivik, Nunavut. Despite the hugely expensive second-hand submarines bought from Britain a few years ago, the report noted that Canada had no Arctic submarine capabilities.49 One need only to contrast Canada’s meagre presence in the region to the American military establishment in Alaska or, more appropriately, given the size of the country, Australia’s military facilities in the Northern Territory. By any appropriate international standard, Canada’s capacity to defend and protect its northern region is woefully weak. It is hardly a surprise, consequently, that Canadians are worried about a major challenge to Canada’s control over the region.

Military operations in the Far North are resource intensive. Far beyond the national highway and rail network, heavy transport aircraft provide essential support to sustain exercises. DND photo IS2008-3002

The Conservatives and the New Northern Policy

“Use it or lose it” is how Prime Minister Stephen Harper summed up Canada’s options in the Far North. The blunt message is characteristic of the Conservative government’s approach to sovereignty issues, although the policy and investments have, so far, lagged behind the rhetoric. The reality is that Canada has not had a significant presence in the Arctic for years. As political editor Andy McSmith commented in The Independent (London) in July 2007, Canada “looks like being the loser in a race to conquer planet Earth’s final frontier.”50 There have been useful steps in the past—supporting the creation of the Arctic Council, the establishment of Nunavut and land claims settlements in the Northwest Territories, assisting with the early development of the University of the Arctic— but the overall level of commitment has been minimal compared to Canada’s circumpolar neighbours. The Arctic sovereignty debate has dovetailed nicely with the Conservatives’ growing concern about the state of national defence, a desire to improve the facilities and capacity of the Canadian military, and a stronger belief than previous governments in the importance of independent action in the North.

The Harper government has held to the long-standing Canadian position that the Northwest Passage is internal waters and consequently under Canadian control. Brad Morse, a leading legal scholar, says of the Canadian position: “Canada’s claim is reasonably strong but far, far from being airtight as Canada has consistently paid little attention to the Northwest Passage and the High Arctic.”51 In a bad case of the revenge of the past, the country’s long-standing neglect of the Far North has the potential to shape Canada’s future. Alex Wolfe, of the University of Alberta, puts it simply: “The current levels of interest and activity would make such a claim at present laughable to other polar nations. Canada has neglected the North, its people and its relevance at large for generations. We are simply paying for it now.”52

Other commentators believe that Canada should be more confident, emphasizing that Canada’s relationship with the United States has been generally positive in the North, and that the Americans do not have malevolent designs to usurp Canada’s Arctic regions. In this vein, “agreeing to disagree” remains a feasible strategy. There is no conventional military threat in the Arctic, nor will Canada solve its boundary disputes with the force of arms, but Canadians need to invest in military capabilities in the North so that it can operate in all parts of the country. Furthermore, the Canadian Forces plays a supporting role to civil authorities, namely, the Coast Guard and the RCMP, which have a limited presence and capabilities to deal with criminal activities or emergencies in the region. The rationale for a more robust military presence should not be so that Canada can stand up to the United States and its circumpolar neighbours with modern naval ships, intimidating them into submission with the latest weaponry. Everyone in the region has national interests at stake, but that should be self-evident. Instead, being a good neighbour means having the ability to control your territory and waters so that you don’t have to rely on your friends to do so, which, in Canada’s case, usually makes us jittery and launches another round of sovereignty crises!

For his part, Prime Minister Harper has discovered what all Canadian politicians learn in the cradle: that standing up to the Americans makes both for great theatre and successful Canadian politics, particularly for a party considered to be far too chummy with the Republican administration of the despised George W. Bush. As the Toronto Star editorialized, “Still, it’s all grand politics. Canadians—even those who have never traveled north of Bloor St.—maintain a sentimental attachment to the Arctic. Nothing gets the blood stirring more than the idea of nefarious Yankees trampling all over this particular national icon.”53 Rob Huebert, of the Centre for Military and Strategic Studies, summarized the situation succinctly: “Some issues go beyond rationality. Any sign of an affront to northern sovereignty is absolutely guaranteed to get on the front page of all the newspapers.”54 Historian Jack Granatstein weighed in with his thoughts: “The Danes are trying to get Hans Island, and do not accept our claims in the Arctic—they claim the North Pole. The protection of the Arctic is a key national interest.”55

The government’s position largely ignored a crucial reality, described in detail earlier: the fact that Canada had for decades tolerated American military incursions into the Arctic, in kind of a “Please Ask, Do Tell” approach to Canadian sovereignty. As U.S. president Ronald Reagan indicated, the sovereignty issue should be put to the side, with the Americans agreeing not to act in the Arctic without Canadian permission. John Noble, a Canadian diplomat assigned to the U.S. Relations Branch, observed of the growing problem: “Rather than trying to make a big issue out of this matter, both countries should be proclaiming that the Arctic is an area where we do co-operate and have come to a pragmatic solution to a difficult legal problem.”56

In December 2004, Prime Minister Paul Martin issued a comprehensive northern strategy. The policy called for more money for northern affairs, but little change in direction. The goals were all laudable—protect fragile Arctic ecosystems, expand research activity, and empower aboriginal communities and regional governments—but the strategy lacked both a sense of scale and urgency. The audience for the strategy was internal; it was designed to demonstrate to Canadians that the federal government was serious about the North. While Prime Minister Martin had a strong personal commitment to the North, the policy represented a small advance on long-standing approaches to the Arctic. It did not, in any real way, represent a bold assertion of Canadian interests in the Far North. Martin, like prime ministers before him, was hamstrung by a simple political reality: there are precious few votes in the Arctic region and little southern interest in the North generally. Until and unless Canadian control of the Arctic is questioned, Canadians are generally very happy to continue in a “fit of absence of mind” about their vast northern lands.

Stephen Harper, elected in January 2006, made the defence of Canadian sovereignty a significant part of his pledge for “Canada’s New Government.” Harper addressed Arctic questions in the first press conference after his January 2007 election, mincing few words in sending a strong message to the United States. He criticized U.S. ambassador David Wilkins for repeating the long-standing American rejection of Canada’s claims to the Northwest Passage. “The United States defends its sovereignty. The Canadian government will defend our sovereignty,” Harper said, laying down a firm challenge to his American counterparts. His minority government had strong plans for the Far North, promising to build military icebreakers, upgrade underwater and aerial surveillance capabilities, build a deep-water port, and expand Canada’s military presence in the area. Gordon O’Connor, Harper’s defence minister, commented, “There certainly is a need for us to play in the world and represent Canada in the world, but we also had to make sure that at home we had enough resources to ensure reasonable security, and to protect our sovereignty. In the south, we’ve got to think about terrorism, but in the north, there are issues of sovereignty.”57

At the same time, Canada stepped up military activities in the North. As one soldier, Master Corporal Chris Fernandez-Ledon, observed, in a classic statement on the nature of Canada’s military approach to the North, “Down there [Afghanistan] it was war fighting we were doing. Here you don’t have to worry about people shooting you and ambushing you. You just keep an eye on each other and have fun.”58 National Defence also launched Operation Nunalivut (“the land is ours”) in the late winter of 2006. The expedition involved forty-six military personnel, including over thirty Canadian Rangers, travelling in five separate patrols over land and ice to reach Resolute Bay. Major Chris Bergeron then led an even smaller seven-person group to Alert Bay, at the tip of Ellesmere Island, where the Rangers deposited a metal Canadian flag—yet another symbolic assertion of Canadian sovereignty, of the sort that has been made for the past hundred years. It was, for Canada, an impressive $1-million display of national interest in the North, and a symbolic training exercise for a country that had questionable capacity to respond to military or civilian crises in the North. Compared to the growing Russian military presence in their Arctic and the formidable air and land resources stationed in Alaska by the Americans, critics saw our military effort as pathetic—a pitiful reminder of Canada’s limited capacity to operate in the Far North.

Members of 1 Canadian Ranger Patrol Group at the magnetic north pole off Isaachsen, Nunavut, in 2002. Enhanced sovereignty patrols encourage Rangers to extend their surveillance over parts of the Arctic that are rarely visited by human beings. Photo 1 Canadian Ranger Patrol Group

The Conservatives had proposed a major investment in defence in their 2006 election campaign and, in office, announced their determination to proceed. They proposed to spend over $5 billion on the surveillance system and a port in Iqaluit—although subsequent Conservative budgets did not set aside the required funds. It was not immediately clear if the government would opt for icebreakers—used primarily for civilian purposes—or for naval vessels designed for military operations. Canada’s aging and small fleet of Coast Guard icebreakers, none with the capacity to operate in the thick ice of the High Arctic, had become a national embarrassment, leaving the country as the only Arctic nation without the capacity to work properly in the region. The government committed $720 million in its February 2008 budget for a new icebreaker, which would give Canada the capability to go “anywhere, anytime” in the Arctic, but critics told journalist Bob Weber “that splashy polar programs have been promised before, only to be quietly cancelled once they’ve been milked for political gain.”59 If it takes Canada as long to develop a military presence in the North as it has to replace its Sea King helicopters, there will be no ice at all, and perhaps palm trees, in the High Arctic before any troops arrive at their new base. Norway, in contrast, is investing heavily in new-generation Arctic vessels, under development at the Aker Yards, which will have enhanced capacity to navigate in thick ice conditions. President Vladimir Putin indicated that Russia intended to play in these waters as well, declaring an intent to expanding facilities for the construction of ships capable of working in the Arctic Ocean.