The Bell Curve Is a Curve Ball

There is no defense or security for any of us

except in the highest intelligence and development of all.

BOOKER T. WASHINGTON

My brother Hugh once told me about a professional football coach who stands before his players at the first session of spring training, holds up a football, and says, “Gentlemen, this is a football.”

I am particularly fond of this story because it is a reminder that most of us could use a little coaching to do our best, even at long-accustomed tasks. That is at least as true of parenting as it is of football.

Recent discoveries in neuroscience, molecular biology, and psychology have given researchers a whole new understanding of when and how the human brain develops. Their findings are a crucial kind of coaching that can show parents and other caregivers how to elicit a child’s full potential. The rest of the village can, if we listen in, pick up information and ideas that will help us to steer our communities’ efforts and our nation’s policies in a more productive direction for children. Above all, this new information makes clear that a child’s character and potential are not already determined at birth.

THE BELIEFS we hold about why children think, feel, and behave in certain ways have a tremendous impact on how we treat them. When those beliefs are inaccurate, the consequences can be dire.

During law school, I worked with the staff of the Yale–New Haven Hospital in Connecticut to help draft guidelines for the treatment of abused children. Sometimes these children were brought into the emergency room by parents who themselves had inflicted the injuries. Often the parents denied what they had done, but sometimes they tried to justify it. One father who brought in his badly injured three-year-old claimed that he had beaten the boy to “get the devil out of him.” Behind his horrifying actions lurked the belief that babies are born either good or bad. If their fundamental nature is “bad,” as evidenced by behavior like persistent crying, this crazy logic goes, they must be punished, beaten if necessary. (Never mind that the “remedy” generally has the perverse effect of encouraging “bad” children to live up to their label.)

That same year, I also studied children at the Yale Child Study Center. One of the people I was privileged to work with was the late Dr. Sally Provence, a pioneer in the field of infant behavior. I remember watching her work with a mother who had brought in her seven-month-old son because he was having trouble eating and sleeping. The mother was at her wits’ end and feared she might hurt her baby. She didn’t understand what was wrong with him, but instead of writing him off as a “bad” child, she’d had the wisdom to seek help.

Under Dr. Provence’s gentle questioning, the woman revealed that her first pregnancy, which resulted in the birth of a girl, had been a joyous experience, and her daughter was an “easy” child. But her second pregnancy had been strained by marital and other tensions in her life, which had persisted. Dr. Provence helped the woman to see that even though her son had a different and more difficult temperament than her daughter, the problems she was having with him stemmed mostly from his keen awareness of her feelings of distress when she was around him. The two of them were caught in a cycle, and as the months went by, the baby’s prospects for healthy development were spiraling downward.

With Dr. Provence’s guidance, the mother learned to change the way she behaved around her son. She learned how to soothe him when he became fussy by holding him snugly. She talked to him more, in a gentler voice. Her new way with him allowed him to relax and become more manageable, which in turn softened her attitude toward him and restored her confidence in her abilities as a parent.

It is not only parents who need expert “coaching” in children’s development. The rest of the village does too. In my years of work with children’s organizations—the Carnegie Council on Children, the Children’s Defense Fund, and the Arkansas Advocates for Children and Families, for example—I saw many dedicated souls trying to see that current knowledge guided practical decisions about children’s welfare.

Once, about fifteen years ago, I represented an Arkansas couple who wanted to adopt a four-year-old boy who had been in their foster care for three years. The boy had been badly neglected as a baby by his biological mother, who was overwhelmed by psychological problems. When he was less than a year old, she turned him over to the local social service agency so she could follow her boyfriend to another state. At that point, the baby showed all the symptoms of severe mistreatment: he had gained little weight since birth, he was unresponsive, and he shied away from human contact.

In his foster family, however, the boy began to thrive. He put on weight and began to allow people to touch him. He learned to walk and began talking. His foster parents fell in love with him and decided they wanted to adopt him, even though they had signed the customary contract with the state, which at that time prohibited foster parents from trying to adopt children in their care. The state adoption agency, reluctant to break precedent, had refused their request. At the same time, however, the agency decided not to return the boy to his birth mother, who had filed suit to get him back, claiming she had overcome her psychological problems and was fit to care for him. Instead, the state planned to take him from the security of the family he knew and turn him over to strangers whose names were on the adoption lists.

I argued on behalf of the boy’s foster parents that the best interests of the child should take precedence over both the birth mother’s claims of her biological rights and the state’s claims to its contractual agreement. I asked the judge to allow testimony from a child psychologist about the boy’s progress while he had been in the care of his foster parents, and about the possible consequences to his physical, intellectual, and emotional development if he was now separated from them. The judge, who had children and grandchildren of his own, did not think that he had much to learn about child development, but he agreed to hear the testimony.

The psychologist explained how disrupting warm and secure attachments like those the boy had formed with his foster family could irreversibly damage his emotional development. He described the symptoms and stages of grief that would typically accompany so great a loss at this age: anger and hostility, renewed withdrawal from human contact, depression and emotional detachment. At his stage of psychological development, the boy would also be inclined to believe he had been deliberately rejected by the foster parents he had come to trust and love. The testimony of the child psychologist riveted the entire courtroom, and it weighed heavily in the judge’s determination that allowing the foster parents to adopt the boy served his best interests.

The years since I had these experiences have been light-years in terms of the progress researchers have made in understanding children’s emotional and cognitive development. Unfortunately, much of this information is not yet known to enough people. At the risk of grossly oversimplifying the research, I want to summarize what is known, with the hope of reaching people whose attitudes toward and treatment of children might benefit from it.

Some of the most significant headway has been made in the field of biology, where researchers have begun to grasp how the brain develops.

At birth, an infant’s brain is far from fully formed. In the days and weeks that follow, vital connections begin to form among the brain cells. These connections, called synapses, create the brain’s physical “maps,” the pathways along which learning will take place, allowing the brain to perform increasingly complicated tasks. A newborn’s brain is like an orchestra just before the curtain goes up, the billions of instruments it will need to express itself in language, thought, and impulse furiously tuning up.

The first three years of life are crucial in establishing the brain cell connections. But they don’t form in a vacuum. Babies need food for their brains as well as their bodies, not only good physical nourishment but loving, responsive caregiving from their parents and the other adults who tend to them. They need to see light and movement, to hear loving voices, and, above all, to be touched and held.

As science writer Ronald Kotulak explained in a series of Pulitzer Prize–winning articles in the Chicago Tribune, “The outside world is indeed the brain’s real food…[which it] gobbles up…in bits and chunks through its sensory system: vision, hearing, smell, touch, and taste.” He quotes psychiatrist Felton Earls of Harvard University’s School of Public Health, who elaborates, “Just as the digestive system can adapt to many types of diets, the brain adapts to many types of experiences.”

Kotulak uses an analogy from cyberspace to make the process clearer. If we conceive of the brain as the most powerful and sophisticated computer imaginable, the child’s surroundings act like a keyboard, inputting experience. The computer comes with so much memory capacity that for the first three years it can store more information than an army of humans could possibly input. By the end of three or four years, however, the pace of learning slows. The computer will continue to accept new information, but at a decreasing rate. The process continues to slow as we mature, and as we age our brain cells and synapses begin to wither away.

What sets the brain apart from any computer in existence, however, is its fragile and ongoing relationship to the world around it. The brain is an organ, not a machine, and its “hardware” is still being wired at birth, and for a long time afterward. With proper stimulation, brain synapses will form at a rapid pace, reaching adult levels by the age of two and far surpassing them in the next several years. The quality of the nutrition, caregiving, and stimulation the child receives determines not only the eventual number of these synapses but also how they are “wired” for both cognitive and emotional intelligence. Synapses that are not used are destroyed.

As neuroscientist Bob Jacobs says, the bottom line is: “You have to use it or you lose it.” If we think of the brain as our most important muscle, we can appreciate that it requires activity in order to develop. Just as babies need to flex their arms and legs, they also need regular, varied stimulation to exercise all the parts of their brains.

When parents talk to their babies, for example, they are feeding the brain cells that process sound and helping to create the connections necessary for language development. A University of Chicago study showed that by the age of two, children whose mothers had talked to them frequently since infancy had bigger vocabularies than children from the same socioeconomic backgrounds whose mothers had been less talkative.

What I am passing along to you is a bare-bones description of what scientists believe happens within the developing brain; the processes are more complex than I can do justice to, and they are not yet fully understood. But it is clear that by the time most children begin preschool, the architecture of the brain has essentially been constructed. From that time until adolescence, the brain remains a relatively eager learner with occasional “growth spurts,” but it will never again attain the incredible pace of learning that occurs in the first few years.

Nevertheless, as long as our brain stays healthy, we will have plenty of synapses left for learning. Even late in life, and even after a long diet of mental “junk food,” the brain retains the capacity to respond to good nourishment and proper stimulation. But neurologically speaking, playing catch-up is vastly more difficult and costly, in terms of personal sacrifice and social resources, than getting children’s brains off to a good start in the first place.

THE PICTURE of the brain as a developing organ that has begun to emerge from biological research dovetails with some key findings from the world of psychology. Nowhere is this more welcome than in the study of what constitutes intelligence, an area of inquiry that has been clouded by controversy, misinformation, and misinterpretation.

It has become fashionable in some quarters to assert that intelligence is fixed at birth, part of our genetic makeup that is invulnerable to change, a claim promoted by Charles Murray and the late Richard Herrnstein in their 1994 book, The Bell Curve. This view is politically convenient: if nothing can alter intellectual potential, nothing need be offered to those who begin life with fewer resources or in less favorable environments. But research provides us with plenty of evidence that this perspective is not only unscientific but insidious. It is increasingly apparent that the nature-nurture question is not an “either/or” debate so much as a “both/and” proposition.

Dr. Frederick Goodwin, former director of the National Institute of Mental Health, cites studies in which children who could be described as being “at risk” for developmental problems were exposed at an early age to stimulating environments. The result: The children’s IQ scores increased by as much as 20 points. A similar study, best known as the Abecedarian Project, examined this same process in a long and intensive research effort begun under the leadership of psychologist and educator Craig Ramey at the University of North Carolina in the early 1970s.

Ramey gathered together a group of more than a hundred newborns, most of them African-Americans. Their parents, most of whom had not graduated from high school, had an average IQ of 85. The majority of the families were living on welfare.

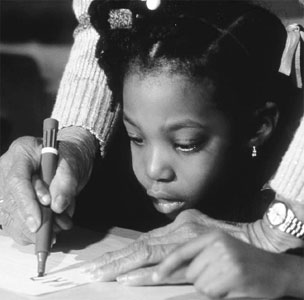

At the age of four months, half of the children were placed in a preschool with a very high ratio of adult staff to children. But it wasn’t only the attention these children were given that was special. When adults spoke to them, they used words that were descriptive and that were suited to the child’s stage of learning. They were doing precisely what responsive parents do when they communicate with their young sons and daughters.

The children in this group were given good nutrition, educational toys, and plenty of other stimulation, as well as the encouragement to explore their surroundings. A “home-school resource teacher” met with each family every other week to coach the parents on how to help their children with school-related lessons and activities.

By the time the children were three years old, those in the experimental group of children averaged 17 points higher on IQ tests than the other half of the original group, 101 versus 84. Even more significant than these impressive gains is their durability: the differences in IQ persisted a decade later, when the children were attending a variety of other schools. Dr. Ramey is continuing to follow the children to see what their further development brings.

Bear this research in mind when you listen to those who argue that our nation cannot afford to implement comprehensive early education programs for disadvantaged children and their families. If we as a village decide not to help families develop their children’s brains, then at least let us admit that we are acting not on the evidence but according to a different agenda. And let us acknowledge that we are not using all the tools at our disposal to better the lives of our children.

ANY DISCUSSION of how the brain’s processes affect cognitive intelligence tells only half the story about the first blossoming of intelligence. The other half is how we behave in our relations with other people—what is now being called our “emotional intelligence.”

One unusual aspect of living in the Arkansas governor’s mansion was getting to know prison inmates who were assigned to work in the house and the yard. When we moved in, I was told that using prison labor at the governor’s mansion was a longstanding tradition, which kept down costs, and I was assured that the inmates were carefully screened. I was also told that onetime murderers were by far the preferred security risks. The crimes of the convicted murderers who worked at the governor’s mansion usually involved a disagreement with someone they knew, often another young man in their neighborhood, or they had been with companions who had killed someone in the course of committing another crime.

I had defended several clients in criminal cases, but visiting them in jail or sitting next to them in court was not the same as encountering a convicted murderer in the kitchen every morning. I was apprehensive, but I agreed to abide by tradition until I had a chance to see for myself how the inmates behaved around me and my family.

I saw and learned a lot as I got to know them better. We enforced rules strictly and sent back to prison any inmate who broke a rule. I discovered, as I had been told I would, that we had far fewer disciplinary problems with inmates who were in for murder than with those who had committed property crimes. In fact, over the years we lived there, we became friendly with a few of them, African-American men in their thirties who had already served twelve to eighteen years of their sentences.

I found myself wondering what kind of experiences and character traits had led them to participate in the violent and self-destructive acts that landed them in prison. The longer and better I came to know them, the more convinced I became that their crimes were not the result of inferior IQs or an inability to apply moral reasoning. Although they had not finished high school, they seemed to have active and inquisitive minds. Some had whimsy as well as street smarts. They showed sound judgment in solving problems in their work, and they plainly knew the difference between right and wrong. What, I wondered, had caused them to commit a crime that resulted in the loss of another’s life?

Now that I have read Daniel Goleman’s Emotional Intelligence, I am better able to understand what back then I could only wonder about.

Goleman brings to our attention new breakthroughs in psychology and neuroscience that shed light on how our “two minds”—the rational and the emotional—operate together to determine human behavior. Both forms of intelligence are essential to human interaction, and as any parent or teacher can tell you, both are constantly at work. If rational intelligence is unchecked by feeling for others, it can be used to orchestrate a holocaust, run a drug cartel, or carry out serial murders.

The power of emotion is equally dangerous if it is not harnessed to reason. People who cannot control their emotions are often prone to impulsive overreaction. They may be quick to perceive threats and slights even when none are intended, and to respond with violence. They are, in Goleman’s phrase, “emotional illiterates.” Many of the gang members interviewed as part of a recent study released by Attorney General Janet Reno to investigate the extent of illegal use of firearms fit this profile. More than one in three said they believe it is acceptable to shoot someone who “disses” them—shows them disrespect.

As with cognitive intelligence, the development of emotional intelligence appears to hinge on the interplay between biology and early experience. Early experience—especially how infants are held, touched, fed, spoken to, and gazed at—seems to be key in laying down the brain’s mechanisms that will govern feelings and behavior. Some experts speculate that the brains of emotional illiterates are hard-wired early on by stressful experiences that inhibit these mechanisms and leave people prey to emotional “hijacking” ever after.

Most of us don’t habitually react with impulsive violence, but all of us “blow our tops,” give in to irrational fears, or otherwise feel overwhelmed—hijacked—by our emotions from time to time. Why do we, as thoughtful human beings, allow emotional impulse to override rational thinking?

As Goleman explains, the temporary “hijackings” are ordered by the amygdala, a structure in the oldest, most primitive part of the brain, which is thought to be the physical seat of our emotions. This brain structure acts like a “home security system,” scanning incoming signals from the senses for any hint of experience that the primitive mind might perceive as frightening or hurtful.

Whenever the amygdala picks up such stimuli, it reacts instantaneously, sending out an emergency alarm to every major part of the brain. This alarm triggers a chain of self-protective reactions. The body begins to secrete hormones that signal an urgent need for “fight or flight” and put a person’s senses on highest alert. The cardiovascular system, the muscles, and the gut go into overdrive. Heart rate and blood pressure jump dramatically, breathing slows. Even the memory system switches into a faster gear as it scans its archives for any knowledge relevant to the emergency at hand.

The amygdala acts as a storehouse of emotional memories. And the memories it stores are especially vivid because they arrive in the amygdala with the neurochemical and hormonal imprint that accompanies stress, anxiety, or other intense excitement. “This means that, in effect, the brain has two memory systems, one for ordinary facts and one for emotionally charged ones,” Goleman notes. And he adds, “A special system for emotional memories makes excellent sense in evolution, of course, ensuring that animals would have particularly vivid memories of what threatens or pleases them. But emotional memories can be faulty guides to the present.”

Problems arise because the amygdala often sends a false alarm, when the sense of panic it triggers is related to memories of experiences that are no longer relevant to our circumstances. For example, traumatic episodes from as far back as infancy, when reason and language were barely developed, can continue to trigger extreme emotional responses well into adulthood.

The neocortex—the thoughtful, analytical part of the brain that evolved from the primitive brain—acts as a “damper switch for the amygdala’s surges.” Most of the time the neocortex is in control of our emotional responses. But it takes the neocortex longer to process information. This gives the instantaneous, extreme responses triggered by the amygdala a chance to kick in before the neocortex is even aware of what has happened. When this occurs, the brain’s built-in regulatory process can be short-circuited.

Most people learn how to avoid emotional hijackings from the time they are infants. If they have supportive and caring adults around them, they pick up the social cues that enable them to develop self-discipline and empathy. According to Dr. Geraldine Dawson of the University of Washington, the prime period for emotional development appears to be between eight and eighteen months, when babies are forming their first strong attachments. As with cognitive development, the window of change extends to adolescence and beyond, although it narrows over time. But children who have stockpiled painful experiences, through abuse, neglect, or exposure to violence, may have difficulty enlisting the rational brain to override the pressure to display destructive and antisocial reactions later in life.

The answer to Goleman’s essential question—“How can we bring intelligence to our emotions—and civility to our streets and caring to our communal life?”—appears to be that, difficult as it may be, it is never too late to teach the elements of emotional intelligence. The structure imposed by the responsibilities of work and the enlightened assistance of concerned people in the prison system and at the governor’s mansion helped those onetime murderers I knew in Arkansas to achieve a greater understanding of and control over their feelings and behavior.

A number of schools around the country are incorporating the teaching of empathy and self-discipline—what social theorist Amitai Etzioni calls “character education”—into their curricula. In New Haven, Connecticut, a social development approach is integrated into every public school child’s daily routine. Children learn techniques for developing and enhancing social skills, identifying and managing emotions like anger, and solving problems creatively. The program appears to raise achievement scores and grades as well as to improve behavior.

WE ARE beginning to act—albeit slowly—on the evidence biology and psychology provide to us. But practice lags far behind research findings. As Dr. Craig Ramey notes, “If we had a comparable level of knowledge with respect to a particular form of cancer or hypertension or some other illness that affected adults, you can be sure we would be acting with great vigor.”

If, in scientific terms, the twentieth century has been the century of physics, then the twenty-first will surely be the century of biology. Not only are scientists mapping our genetic makeup, but new technologies are letting them peer into living organisms and view our brains in action. The question we must all think about is whether we will put to good use this accumulating knowledge. Can we find ways to communicate it to all parents, so that it can help them to raise their children and to seek out coaching if they need it? Will we give working mothers and fathers enough time to spend feeding their babies’ brains? Will we have the foresight and the political will to provide more and better early education programs for preschoolers, especially those from homes without adequate “brain food”? Will we challenge elementary school students with foreign languages, math, and music to reinforce brain connections early in a child’s life? Given the increasing level of violence and family breakdown we see around us, why wouldn’t we?

IN THE next few chapters I will explore what happens in families during the first few years of children’s lives—the period that we now know is so vital in giving them a solid start. Researchers may differ over how particular experiences influence a child’s development, but no research study I have ever read has disputed that the quality of life within the family constellation strongly affects how well infants and young children will adapt to the circumstances that confront them throughout their lives. On the contrary, the research underscores the critical importance of constructive stimulation during a child’s earliest years.

But if family life is chaotic, if parents are depressed and unexpressive, or if caregivers change constantly, so that children can rely on no one, their ability to perform the essential tasks of early childhood will be impaired. The next time you hear someone using the word “investment” to describe what we need to do for our younger, more vulnerable family members, think about the investments the village has the power to make in children’s first few weeks, months, and years. They will reap us all extraordinary dividends as children travel through the crucial stages of cognitive and emotional development to come.