Kids Don’t Come with Instructions

We learn the rope of life by untying its knots.

JEAN TOOMER

There I was, lying in my hospital bed, trying desperately to figure out how to breast-feed. I had been trained to study everything forward, backward, and upside down before reaching a conclusion. It seemed to me I ought to be able to figure this out. As I looked on in horror, Chelsea started to foam at the nose. I thought she was strangling or having convulsions. Frantically, I pushed every buzzer there was to push.

A nurse appeared promptly. She assessed the situation calmly, then, suppressing a smile, said, “It would help if you held her head up a bit, like this.” Chelsea was taking in my milk, but because of the awkward way I held her, she was breathing it out of her nose!

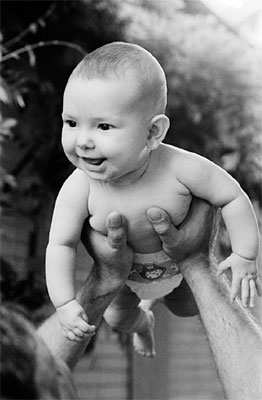

Like many women, I had read books when I was pregnant—wonderful books filled with dos and don’ts about what babies need in the first months and years to ensure the proper development of their bodies, brains, and characters. But as every parent soon discovers, grasping concepts in the abstract and knowing what to do with the baby in your hands are two radically different things. Babies don’t come with handy sets of instructions.

How well I remember Chelsea crying her heart out one night soon after Bill and I brought her home from the hospital. Nothing we could do would quiet her wailing—and we tried everything. Finally, as I held her in my arms, I looked down into her little bunched-up face. “Chelsea,” I said, “this is new for both of us. I’ve never been a mother before, and you’ve never been a baby. We’re just going to have to help each other do the best we can.”

In her classic book Coming of Age in Samoa, Margaret Mead observed that a Samoan mother was expected to give birth in her mother’s village, even if she had moved to her husband’s village upon marriage. The father’s mother or sister had to attend the birth as well, to care for the newborn while the mother was being cared for by her relatives. With their collective experience as parents, they helped ease the transition into parenthood by showing how it was done.

In our own American experience, families used to live closer together, making it easier for relatives to pitch in during pregnancy and the first months of a newborn’s life. Women worked primarily in the home and were more available to lend a hand to new mothers and to help them get accustomed to motherhood. Families were larger, and older children were expected to aid in caring for younger siblings, a role that prepared them for their own future parenting roles.

These days, there is no shortage of advice, equipment, and professional expertise available to those who can pay for it. If breast-feeding is a problem, for example, there are lactation specialists, state-of-the-art breast pumps, and more books on the subject than you can count. But nothing replaces simple hands-on instruction, as I can attest. People and programs to help fledgling parents are few and far between, even though such help costs surprisingly little. We are not giving enough attention to what ought to be our highest priority: educating and empowering people to be the best parents possible.

Education and empowerment start with giving parents the means and the encouragement to plan pregnancy itself, so that they have the physical, financial, and emotional resources to support their children. Some of the best models for doing this come from abroad. I’m reminded in particular of a clinic I visited in a rural part of Indonesia.

Every month, tables are set up under the trees in a clearing, and doctors and nurses hold the clinic there. Women come to have their babies examined, to get medical advice, and to exchange information. A large poster-board chart notes the method of birth control each family is using, so that the women can compare problems and results.

This clinic and thousands like it around that country provide guidance that has led mothers to devote more time and energy to the children they already have before having more. The fathers, I was told, have also been affected by the presence of the clinic. They are more likely to judge their paternal role by the quality of life they can provide to each child than by the number of children they father.

This community clinic program, which is funded by the government and supported by the country’s women’s organizations and by Muslim leaders, is a wonderful example of how the village—both the immediate community and the larger society—can use basic resources to help families. The honest, open, matter-of-fact manner of dealing with family planning issues that I observed in Indonesia provided me with a point of comparison to the approaches I have observed in many other places.

The openness about sexuality and availability of contraception in most Western European countries are credited with lowering rates of unintended pregnancy and abortion among adolescent and adult women. By contrast, more than one hundred million women around the world still cannot obtain or are not using family planning services because they are poor or uneducated, or lack access to care. Twenty million women seek unsafe abortions each year.

In October 1995, I saw a striking example of the consequences when I visited the Tsyilla Balbina Maternity Hospital in Salvador da Bahia, Brazil. I learned that half the admissions there were women giving birth, while the other half were women suffering from the effects of self-induced abortions. I met with the governor and the minister of health for the state, who have launched a campaign to make family planning available to poor women. As the minister pointed out to me, rich women have always had access to such services.

We may think that our country is far from this end of the spectrum, but the statistics tell a different story. Two in five American teenage girls become pregnant by the age of twenty, and one and a half million abortions are performed in America each year. It is a national shame that many Americans are more thoughtful about planning their weekend entertainment than they are about planning their families. And it is tragic that our country does not do more to promote research into family planning and wider access to contraceptive methods because of the highly charged politics of abortion. The irony is that sensible family planning here and around the world would decrease the demand for legal and illegal abortions, saving maternal and infant lives.

As usual, the children pay. When too-young parents have children, or when families expand without the means to support their growth, children are affected by the burdens and anxieties of parents who cannot meet their obligations. Family planning, more than just limiting the number of children parents have, protects the welfare of existing and future children.

The Cairo Document, drafted at the International Conference on Population and Development in 1994, reaffirms that “in no case should abortion be promoted as a method of family planning.” And it recognizes “the basic right of all couples and individuals to decide freely and responsibly the number, spacing, and timing of their children and to have the information and means to do so.” Women and men should have the right to make this most intimate of all decisions free of discrimination or coercion.

Once a pregnancy occurs, however, we all have a stake in working to ensure that it turns out well.

THERE IS no experience more moving than to walk through a neonatal intensive care unit crowded with babies born too early—the whir of the ventilating machines, the rushing about, the smell of newborns mixed with the smells of hospital halls, the tangle of tubes inserted into wrinkled little bodies. I have walked through many such units in my lifetime, in Washington, Chicago, Little Rock, Boston, Oakland, Miami. The scenes are all the same—babies no bigger than my hand fighting for a life they’ve barely tasted.

In a 1992 study by the World Health Organization, the United States ranked twenty-fourth among nations in infant mortality. That means twenty-three countries, led by Japan, do a better job than we do of ensuring that their babies live until their first birthday. Seventeen countries, led by Italy, have better maternal health than we do. We shouldn’t be surprised at these results, since nearly one quarter of all pregnant women in America, many of whom are teenagers, receive little or no prenatal care.

We know that women who receive prenatal care, especially in the first trimester, are more likely to deliver healthy, full-term, normal-weight babies, while women who do not receive adequate prenatal care are more than twice as likely to give birth to babies weighing less than five and a half pounds, the definition of “low birth weight.” And women who do not receive complete prenatal advice on alcohol and drug use, smoking, and proper nutrition are also more likely to give birth to low-birth-weight babies. In 1991, such babies represented only 7 percent of all births but about 60 percent of all infant deaths, for they were twenty-one times as likely to die before their first birthday as babies born weighing more. Inadequate prenatal care also results in higher rates of preventable problems, including congenital anomalies, early respiratory tract infections, and learning difficulties.

We spend billions of dollars on high-tech medical care to save and treat tiny babies. In 1988, a child born at low birth weight cost $15,000 more in the first year of life than a child born at normal birth weight. It is a modern miracle that we are able to save thousands of babies who would have died if they had been born a few years ago and that we can help thousands more to develop normally. In many cases, however, good prenatal care and emergency obstetric services could have averted the need for medical heroics altogether.

FOR many pregnant women in America, prenatal care is not accessible or affordable. They live in isolated rural areas or in urban centers. Their employers do not offer insurance, and their families do not make enough money to buy it on their own. Even families who have insurance sometimes find that health care is out of their reach. A couple I met told me their story: Having limited resources, they decided to insure their children and the breadwinning father, but not the homemaker mother. When the mother unexpectedly became pregnant, they saved their money to pay the hospital bills and decided to forgo the expense of prenatal care and anesthesia during delivery. This purely economic decision put both mother and baby at risk.

Many pregnant women are not even aware that they should be seeking prenatal care. They may be teenagers in denial about their pregnancy or trying desperately to hide their situation from their families. They may be women who do not have husbands, family, friends, or others concerned and informed enough to encourage them to seek medical attention or, at the very least, to stop smoking, drinking, or taking drugs during the pregnancy. In general, women whose already chaotic lives have been further complicated by pregnancy tend to be reluctant to seek services until the last possible moment, leaving their babies vulnerable to much greater health risks.

Ultimately, we women must take responsibility for ourselves and our health, but many of us will need assistance and support from the village. Peer pressure can work. We all know instances where family and friends have consistently and firmly reminded an expectant mother to forgo an alcoholic drink or a cigarette. But such informal means of monitoring care are no substitutes for formal systems that have as their primary mission good health for all women and babies.

Examples of the village at work can be found in countries where national health care systems ensure access to pre- and postnatal care for mothers and babies. Some European countries, such as Austria and France, tie a mother’s eligibility for monetary benefits to her obtaining regular medical checkups.

While it is doubtful that our country will anytime soon develop a formal means of offering or monitoring prenatal care, there are things we can do now that will lower medical costs for all of us and prepare children for a lifetime of good health, starting before birth.

Some states, health care plans, community groups, and businesses have created their own systems of incentives to encourage women to obtain prenatal care. In Arkansas, we enlisted the services of local merchants to create a book of coupons that could be distributed to pregnant women. This “Happy Birthday Baby Book” contains coupons for each of the nine months of pregnancy and the first six months of a child’s life. After every month’s pre- or postnatal exam, the attending health care provider validates a coupon, which can be redeemed for free or reduced-priced goods such as milk or diapers.

The Arkansas Department of Health, which has run television and radio ads with a toll-free number to obtain the book, estimates that nearly seven out of every ten pregnant women in the state have received the coupon book. Preliminary reports indicate that women who have participated in the coupon program have had fewer low-birth-weight babies.

Businesses have also begun to recognize that preventive care saves health care costs in the long run. Many have begun to provide incentives to encourage their employees to seek prenatal care. Haggar Apparel Company in Dallas, Texas, for example, offers to pay 100 percent of employees’ medical expenses during pregnancy if they seek prenatal care during the first trimester of pregnancy. Levi Strauss in San Francisco offers pregnant employees a $100 cash incentive to call a toll-free “health line,” which provides information and advice to callers and screens them to identify those at risk for early delivery.

Insurance companies, particularly those offering managed care plans, are underwriting classes on healthy lifestyles for pregnant women and providing incentives like car seats and diaper services to encourage women to participate in baby-care training. Other insurance companies are offering one-on-one help, making nurse midwives or nurse practitioners available to pregnant women by phone around the clock.

Projects that team pregnant mothers with knowledgeable counterparts on the phone or in person have been greeted with much enthusiasm. People want to learn to be good parents.

In South Carolina, the Resource Mothers program has been linking pregnant teenagers with experienced mothers who live nearby since the early 1980s. The older women meet with the younger women before and after the baby is born, to teach them basic skills like bathing, changing, and feeding, and also to demonstrate constructive ways of interacting verbally and nonverbally with young children. The teens also receive counseling about the effects of substance abuse during pregnancy and information about child safety and development.

Resource Mothers has already had an impact both in improving the health of babies and in reducing the incidence of child abuse, which is often triggered by parents’ not knowing how to cope with the demands of child rearing. The program is supported by state and federal funds for maternal and child health care and by Medicaid.

In San Antonio, Texas, a program called Avance began teaching basic parenting skills to fifty mothers in 1973. By 1994, the program was serving five thousand individuals in the Mexican-American communities in San Antonio, Houston, and the Rio Grande Valley. Operating in public housing projects, elementary schools, and through its own family service centers, Avance not only enlists project graduates to pass on the basic skills they have learned but offers classes in child development, English-language tutoring, and employment training programs as well.

Avance places a special emphasis on helping young fathers connect to and stay involved with their children. It uses home visits to monitor the progress of young families, keeping open the lines of communication as infants move into early childhood. The success of the program has been measured in the positive attitudes of the young parents it reaches, who learn that their responsibility as parents includes creating a more nurturing and stimulating environment for children. Avance recently received a state grant to build centers in Dallas, Corpus Christi, El Paso, and Laredo over the next few years.

While programs like Resource Mothers and Avance contribute greatly to the success and good health of parents and their babies, there is much that hospitals can do to ensure that parents go home better equipped to cope with the demands of parenthood in the first place.

On a trip to the Philippines, I visited the Dr. José Fabella Memorial Hospital, in one of the poorest sections of Manila. Over the past decade, the hospital has kept newborns with their mothers, not in a separate nursery. In the maternity ward, dozens of new mothers lie in beds facing their babies. Mothers and their tiny ones learn each other’s touch, becoming comfortable together and starting to build a special intimacy.

The doctors and nurses at the hospital spend time at each bedside, patiently teaching mothers how to breast-feed. To my astonishment, I also saw one- and two-day-old infants, mouths pursed, sipping from cups. I learned that the hospital began training mothers who could not breast-feed to use cups once they discovered how difficult it was for poor mothers living in unsanitary conditions to sterilize and clean bottles and nipples. It was much easier and simpler for them to keep a baby’s drinking cup clean. With the money saved from closing the nursery, the hospital hired additional staff to teach basic parenting skills.

American hospitals have also instituted changes in recent decades that encourage both parents to begin caring for their babies in the hospital. Hospitals provide birthing rooms for both labor and delivery. Fathers are allowed to room in and are urged to be present at the birth. Most hospitals that provide delivery services offer basic classes in parenting and child care for new parents.

Hospitals, as the primary point of contact with parents of newborns, have a natural opportunity and a responsibility to help babies and parents get off to a good start. No mother should leave the hospital without being given the opportunity to ask every question she has about proper baby care. A wallet-sized card listing the immunizations a baby needs, when and where to get them, and how much they cost is a useful item hospitals could provide. They could also make available lists of affordable pediatricians in the area.

Perhaps most important, hospitals should evaluate the parent-child relationship to determine whether additional advice and help will be needed. This is critical for teenage mothers. Hawaii has pioneered such a program, Healthy Start, which currently screens more than half of the sixteen thousand babies born in the state each year.

Healthy Start’s workers ask to visit new parents while they are still in the hospital. Most consent to the visit and are grateful that someone cares enough to talk to them. The workers ask them about their family histories and their current situation, noting potential problems. “We look for parents who were abused or neglected as children,” explains Gail Breakey, one of Healthy Start’s founders and the director of the Hawaii Family Stress Center. “We know from research there is an intergenerational pattern.”

If the family is considered to be at risk, Healthy Start offers a follow-up home visitor. The home visitor helps the parents learn about their child’s developmental needs and acts as a liaison with other agencies to make sure that the family’s needs are attended to—from marriage counseling to employment training to drug abuse treatment. Healthy Start has been successful in reducing child abuse to less than 1 percent among the more than three thousand families who have accepted follow-up help over the last five years—far below the national child abuse rate of 4.7 percent. Healthy Start projects now operate in communities in more than twenty-five states.

While Healthy Start operates on a consensual basis, states might also consider making public welfare or medical benefits contingent on agreement to allow home visits or to participate in other forms of parent education.

Despite its proven success, funding for Hawaii’s Healthy Start is not secure. As the federal budget is cut and states are forced to pick up more costs, investments in prevention-oriented programs are likely to take a back seat to prisons, emergency medical care, or other programs with a political constituency.

It is interesting to note that all Western European countries provide some form of home health visitors. England has a long history of providing home visits through its national health service. After mother and newborn child come home from the hospital, a qualified nurse-midwife from the local hospital visits each day for a minimum of ten days. A “family health visitor,” a fully qualified nurse who is usually associated with the local clinic, is also available for phone consultation or home visits upon request from birth until the child goes to school at age five.

An American friend of mine who was living in England during her pregnancy quickly came to appreciate home visits. Before having her baby, she was sure that all the books she was reading would explain everything she needed to know. In any case, she reasoned, her mother planned to arrive by the time the baby did. But her mother became too sick to travel, and my friend found herself home alone with her new baby. Like me, she found that the reading she had done, interesting as it was, left her with lots of unanswered questions. When the nurse came knocking at the door, my friend pulled the startled woman inside and began babbling at her: “Why won’t she sleep for more than an hour? Will she ever open her eyes? Do you think she can hear me?”

I cannot say enough in support of home visits, whether the visitor is a social worker or nurse from a program or an aunt who rides the bus on Saturday to see how her niece and the newborn are doing. Beginner parents need people to talk to and people to call on for help and encouragement.

THE ELECTRONIC village can play a role in assisting rookie parents as well. Radio and television stations could broadcast child care tips between programs, songs, and talk show diatribes. Imagine hearing this kind of “news you can use” sandwiched in the middle of the Top Ten countdown: “So you’ve got a new baby in the house? Don’t let her cry herself red in the face. Just think how you’d feel if you were hungry, wet, or just plain out of sorts and nobody paid any attention to you. Well, don’t do that to a little kid. She just got here. Give her a break. And give her some attention now!”

Videos with scenes of commonsense baby care—how to burp an infant, what to do when soap gets in his eyes, how to make a baby with an earache comfortable—could be running continuously in doctors’ offices, clinics, hospitals, motor vehicle offices, or any place where people gather and have to wait.

I saw another promising innovation in action in the South Bronx in New York City, when I visited Highbridge Communicare Center, which provides basic medical services to the poor residents of the area. Highbridge offers parents a card with a twenty-four-hour toll-free number that connects them to a doctor or nurse who can give them immediate medical advice and help in determining whether a medical problem is serious enough to require either emergency care or an appointment at the clinic. In just a few months of operation, the hot line decreased substantially the number of visits to the local hospital’s emergency room.

Can you imagine a hot line in every community? Local hospitals could pool their resources to sponsor one. Many hours of anxiety and millions of dollars in costs could be avoided if mothers and fathers had someone to call to talk through a baby’s problem instead of showing up at the only place they can think of to find help—the hospital emergency room.

NO MATTER how much advice and information is available to a new mother, she and her baby need adequate time to recover from childbirth before she can put it to use. Yet increasingly, American insurance practices are forcing hospitals to discharge mothers and newborns as quickly as possible. As insurance companies look for more ways to cut costs, new mothers are often rushed out of the hospital only twenty-four hours after an uncomplicated birth and three days after a cesarean. For many women, that just is not enough time to emerge from exhaustion, let alone to learn how to breast-feed properly or adjust to a new sleeping schedule and the other changes that arrive along with the baby.

I was hardly able to get around for the first three days after my cesarean. Fortunately, Bill roomed in at the hospital to care for both me and Chelsea. But almost as soon as I got home, five days after delivery, I had to turn around and go back to the doctor, with a high fever and acute pain from an infection.

A friend of mine who was pregnant with twins began hemorrhaging during labor and had to undergo an emergency cesarean under full anesthesia. After the delivery, she was severely anemic and was placed in intensive care. Even so, her insurance company, basing its decision on a “checklist” of medical factors, said it would not pay for more than three days in the hospital. In the end, the company did cover a longer stay, but only because her doctor spent hours on the phone arguing that it was medically unsafe to send her home. Some doctors won’t take on such battles, because they fear being dropped by the managed care companies with which they do business.

Another friend’s wife was covered for seven days in the hospital after a complicated childbirth. But the insurance company insisted on considering the baby independently of his mother. When my friend was told that meant the child would have to leave after three days, he asked, “Do you expect the baby to walk down to the parking lot and drive himself home?”

Insurance companies claim that limiting a baby’s time in the hospital not only is a money-saver but also reduces exposure to hospital germs. On the other hand, most experts agree that a minimum of forty-eight hours is required to assess the medical risks for mothers and newborns. Generally, new mothers and babies who are discharged in the first twenty-four hours do not develop medical complications. But what happens if the baby develops an infection or other problem—like jaundice, which can cause permanent brain damage or death if it is not treated—that becomes apparent on only the second or third day after birth? What if the new mother has difficulty learning to breast-feed properly, which could result in dehydration or other serious problems for her baby?

In 1992, the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists and the American Academy of Pediatrics released a set of Guidelines for Perinatal Care, which recommended that discharge decisions take into account the medical stability of the mother and infant and whether the mother has learned to feed her baby adequately, been instructed in other basic care, and been informed about the availability of appropriate follow-up supports and services. All of these factors are dependent on the evaluations of doctors and nurses who care for mothers and babies, not of the accountants who pay bills or the patients themselves. (In the dizzying aftermath of childbirth, some mothers may decide they are ready to leave prematurely; others might choose to stay for weeks if permitted.)

Insurance companies point out that most new mothers are entitled to home visits by a nurse, who can help spot problems after they leave the hospital. But the reality is that many insurance companies cover only one home visit per patient; others simply provide for a phone consultation with a nurse in the days after childbirth. And cases have been reported in which the nurse or home visitor simply didn’t show up.

A retired transit worker in New Jersey, Dominick A. Ruggiero, Jr., told this story to the New Jersey legislature earlier this year: His niece had an uneventful pregnancy and childbirth and was discharged after twenty-eight hours. At home, however, her baby, Michelina, suddenly took a turn for the worse. A nurse was supposed to visit the home on the second day, but she never came. When the family called, they were told the visiting nurse wasn’t aware the baby had been born. Several times, the family called the pediatrician, who said the baby had a mild case of jaundice and did not need to be examined. The baby died from a treatable infection when she was two days old.

Thanks in part to Ruggiero’s testimony, New Jersey now has a law that will make sure that insurance covers mothers for a minimum of forty-eight hours in the hospital after uncomplicated deliveries and ninety-six hours following cesarean deliveries. Maryland passed similar legislation last spring, and Congress is now considering a bill that would enforce such provisions nationwide. This is not a partisan issue. Maryland had a Democratic governor and legislature when it acted, and New Jersey’s bill was passed by a Republican legislature and signed by a Republican governor. Pending congressional legislation has sponsors from both parties. Although some have suggested that such laws are another example of unwarranted government intrusion, it is difficult to dispute that the health of new mothers and infants is important enough to be safeguarded by the government.

THE WONDER, worry, and work of parenting does not end with concern about a baby’s physical health. Emotional health and development demand equal attention. The mother-infant ward I visited in Manila took special interest in promoting bonding, the initial contact between parents and child immediately following birth. Watching the mothers and babies there, I remembered how minutes after her birth, Chelsea was cleaned up and handed to me and her father to hold. This initial contact began our lifelong commitment to our child.

My mother, like most American women giving birth in hospitals during the 1940s and ’50s, was under general anesthesia for each delivery. She didn’t breast-feed, because at the time breast-feeding was not encouraged, and she doesn’t remember even seeing me until she was able to walk to the nursery, the day after I was born. She is understandably skeptical about the significance of immediate bonding, but she subscribes wholeheartedly to the importance of establishing in a child’s first year what psychologists call a “secure attachment.” Secure attachment is the foundation of the love and trust children develop in response to warm, dependable, sensitive caregiving. It develops over the first weeks and months of a child’s life, not in the first few minutes.

Our country’s favorite pediatrician, Dr. T. Berry Brazelton, describes how, in the islands of Japan’s Goto archipelago, a new mother stays in bed for a month after delivery, wrapped in a quilt, warmly snuggled with her baby. During that time she has but one responsibility—to feed and hold her newborn. All her female relatives attend her. She herself is considered a child during this time and is spoken to in a sort of baby talk.

Personally, I could do without the baby talk, and a month strikes me as too long to be wrapped in a quilt, but I do admire the way this ritual celebrates and supports a new mother’s most important task: helping her child establish a secure attachment with at least one adult. The secure attachments babies form in the first year give them the security and confidence they will need to explore the world and to develop caring relationships with others.

The smallest attentions to infants’ needs—picking them up when they cry, feeding them when they are hungry, cuddling and holding them—promote the kind of positive stimuli their brains and bodies crave. A psychologist at the University of Miami recently studied two groups of premature babies. Both groups of infants were given state-of-the-art medical care and proper nutrition, but one group also received gentle, loving stroking for forty-five minutes each day. The babies who were touched warmly every day gained weight and developed so rapidly that they were ready to go home six days earlier than babies in the other group. (This simple human contact, resulting in early hospital release of these infants, also saved medical costs of $3,000 a day.)

Gentle, intimate, consistent contact that establishes attachment takes time, and as much freedom as possible from outside stress. The more rushed and harried new parents are, the less patience they will have for the considerable demands of newborns. Infants, of course, have no way of knowing the causes of their parents’ stress, whether it be marital conflict, depression, or financial worries. But we know that babies sense the stress itself, and it may create feelings of helplessness that lead to later developmental problems.

Researchers at the University of Minnesota, one of the premier centers for the study of attachment, have followed almost two hundred people from birth into their twenties. Their findings echo the conclusion reached by scientists conducting research in the area of emotional intelligence: there is a connection between aggression and the lack of secure attachment. “To really understand violence in children,” explains psychologist Allan Sroufe, “you have to also understand why most children and people aren’t violent, and that has to do with a sense of connection or empathy with other people…that is based very strongly in the early relationships of the child and maybe most strongly in the earliest years of life.”

Like other aspects of parenting, establishing a secure attachment with an infant may not come naturally, except in the sense that we are likely to do to our children what was done to us, unless someone or some experience gives us a different model. However, with an open mind and informed guidance, most parents can learn to relate better to their children, regardless of temperament.

Dr. Sally Provence, the child development expert I observed at the Yale Child Study Center, had a gift for reading the subtle signs of babies’ discomfort in the way they reacted to being fed or held, and for teaching parents to do the same so that they could adjust their own behavior accordingly.

I remember standing behind a one-way glass, watching her work with a mother whose baby kept crying and arching his body away from her. The child looked as if he was trying to propel himself into space. I observed how Dr. Provence soothed the baby, speaking to him the same way she touched him, gently but firmly. She translated what she did into simple instructions, for instance showing the mother how to hold the baby less stiffly by using her whole hand instead of just her fingertips. If that kind of hands-on instruction were readily available to more parents, many behavioral and emotional problems could be prevented.

THE VILLAGE can do much to give parents the time they need to establish their children’s well-being in the first weeks and months of life. The Family and Medical Leave Act, the first bill my husband signed into law as President, on February 5, 1993, enables people who work at companies with fifty employees or more to take up to twelve weeks’ leave in order to care for a new child, a sick family member, or their own serious health condition, without losing their health benefits or their jobs. Although the leave is unpaid, and employees at smaller firms are not covered at all, this is a major step toward a national commitment to allowing good workers to be good family members—not only after the birth or adoption of a child but when a child, parent, or spouse is in need.

My husband and I have heard from hundreds of Americans whose lives have already been helped by this historic legislation. One father pushing his daughter in a wheelchair on a tour through the White House saw the President and asked to speak with him. He thanked my husband for making it possible for him to spend time with his little girl, who was dying of leukemia, without fear of losing his job. This is real “family values” legislation.

WE CAN GO much further to allow and encourage parents to be there when children need them, most critically in the earliest weeks and months of life. Children do not arrive with instructions, but they do confer the immense and immediate responsibility of figuring out how best to care for them. Parenting does not all “come naturally,” but ready or not, it comes. The village as a whole owes expectant and new mothers and fathers its accumulated experience and wisdom, and the resources they will need to tackle the important and exciting task ahead.