An Ounce of Prevention Is Worth a Pound of Intensive Care

Health is number one. You can’t have a good offense, a good defense,

good education, or anything if you don’t have good health.

SARAH MCCLENDON

Dr. Betty Lowe, the medical director at Arkansas Children’s Hospital, who has been president of the American Academy of Pediatrics and, most important, one of Chelsea’s doctors, taught me many lessons during the past two decades. Her medical expertise and down-to-earth manner reassured me, and her common sense about preventive health care changed how I thought.

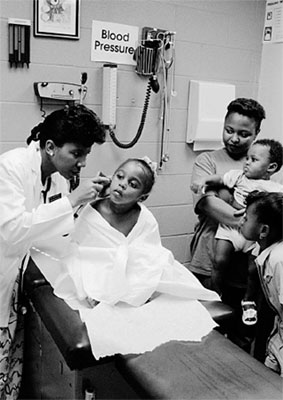

Years ago, we were both speaking to the Little Rock Junior League about children’s needs. After our speeches, a woman in the audience asked Dr. Lowe what she would do to improve the health of children. Without hesitating, she replied that she would guarantee them clean water and good sanitation; nutritious food, vaccinations, and exercise; and access to a doctor when they needed one.

Dr. Lowe explained that the vast majority of children she saw in the hospital ended up there because of adults’ failures to take care of them: the town that failed to clean up the sewage ditch behind some houses; the parents who failed to immunize a baby or to feed a toddler properly; the doctors who failed to accept Medicaid or treat the uninsured; the welfare worker who failed to protect a child from abuse or neglect; the landlord who failed to provide the heat promised in winter or to haul away garbage in summer; the teacher who failed to refer the belligerent or depressed teenager for help.

There’s probably no area of our lives that better illustrates the connection between the village and the individual and between mutual and personal responsibility than health care. Every one of us knows we should take care of our bodies and our children’s bodies if our goal is good health, and many of us try to do that. We also know, though, that we are dependent on others for the health of our environment and for medical care if we or our children become ill or injured. Knowing these things, however, does not always lead either individuals or societies to take action.

The effort to immunize children against preventable childhood diseases is a good illustration of the challenges before us. The American Academy of Pediatrics recommends that babies be taken for preventive checkups and receive appropriate immunizations when they are one, two, four, six, nine, twelve, and eighteen months old, then again at two, three, and four years. We’ve come a long way toward these goals from where we were a few years ago. Our national rate of immunization is higher than it has ever been, and as a result, we are at or near the lowest incidence ever recorded for every vaccine-preventable disease.

Some of this improvement may be due to the increased funding for immunizations and the outreach and education campaigns we have embarked on since my husband took office. We know that when funding for immunization decreased in the past, the incidence of serious disease increased. After the federal government’s immunization funding was cut in the 1980s, a measles epidemic between 1989 and 1991 struck 55,000 people and killed 130 of them, many of them children. Medical costs of the epidemic exceeded $150 million, more than was “saved” by the cutbacks.

Providing funding for the inoculations themselves is key, because the vaccines are expensive and getting more so. In 1983, the private cost for a full series of immunizations was $27. Today the cost is ten times that much for just the shots themselves, and nearly as much again in administrative fees. Although nearly all managed care policies cover immunization costs, about half of conventional health insurance policies do not.

I will never forget the woman from Vermont whom I met at a health care forum in Boston. She ran a dairy farm with her husband, which meant that she was required by law to immunize her cattle against disease. But she could not afford to get her preschoolers inoculated as well. “The cattle on my dairy farm right now,” she said, “are receiving better health care than my children.”

Convenience is also a factor. Until recently, private doctors referred patients without adequate cash or insurance to the public health clinic, the only place families could take their children for free inoculations. But that doesn’t mean the families went. Faced with a hodgepodge of providers, clinics’ inconvenient hours and locations, and long waits, many parents delayed having their kids immunized.

In 1993, as part of a larger initiative to improve immunization rates, Congress adopted the Vaccines for Children program, which provides free vaccines to needy children through private doctors as well as clinics. The initiative also includes state funding to improve outreach and education, lengthen clinic hours, hire additional staff, and expand services. But these advances are already under grave threat from budget cuts.

We have a lot of ground to cover as it is. In immunization rates, we still trail behind a number of other advanced countries and even some less developed ones. And although three out of four of today’s two-year-olds have the proper immunizations (up from about one in four in 1991), that leaves almost 1.4 million toddlers who have not received all the vaccinations they need.

Most parents are aware that immunizations are required for a child to enter school, but many of them, and even some health care providers, don’t know that 80 percent of the required vaccinations should be given by the age of two. That is why the village needs a town crier—and a town prodder.

Kiwanis International, the community service organization, has been both, working to promote the needs of children from prenatal development to age five through an international project called Young Children: Priority One. Among other efforts, the project has launched a national public education campaign, which features my husband on billboards and in public service announcements calling for “all their shots, while they’re tots.”

Two women I greatly admire have campaigned for more than two decades to make sure that children get the vaccinations they need, on time. Rosalynn Carter, a distinguished predecessor of mine who is compassion in action, and Betty Bumpers, the wife of the senior U.S. senator from Arkansas and an energetic advocate for children, have worked with spirit and dedication to persuade Americans to invest the money and energy necessary to ensure that all children receive their immunizations on time. When the measles epidemic began in 1989, they started a nonprofit immunization education program, called Every Child by Two, working with community leaders, health providers, and elected officials at the local, state, and national levels to spread the word about timely immunizations and to establish and expand immunization programs around the country.

We know that requiring children to show proof of immunization before they enter school guarantees that children get their shots by five or six. States and cities looking for similar ways to ensure compliance for toddlers are linking immunization efforts to social service programs. A program in Maryland requires families on welfare to show proof of immunization in order to receive benefits, a requirement I have long advocated. Recent studies in Chicago, New York, and Dallas show that coordinating immunization services with the Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants and Children (WIC) significantly improves immunization rates.

If we can see to it that cows get their shots, we can see that kids do too—before the cows come home.

Of course, cows don’t cry at the sight of hypodermic needles. It takes more than a village to persuade children that the sting of a shot is really in their interest. It helps to explain to the child in advance what the shots do, perhaps by illustrating it with her favorite dolls and stuffed animals. I know parents who take a favorite teddy bear to the doctor’s office to have its “shots” as well. That allows the child to commiserate with the bear when the needle is applied, and the bear to sympathize with the child when her turn comes.

PEDIATRICIANS recommend that children continue to get checkups at five, six, eight, and ten years. From the age of eleven on, the most explosive period of growth after infancy, they should be examined yearly. Between checkups, there are steps each of us can take to keep children healthy. From basic hygiene habits like frequent hand washing to healthier eating and exercise, prevention works.

Let’s talk first about food, as we love to do. This country dreams of food, thinks about it constantly—lemon tarts shimmering under meringue, ribs drenched in barbecue sauce, golden-brown fried chicken, mashed potatoes swimming in butter, and mile-high chocolate pies, beckoning us to indulge, indulge, indulge.

Our passion for food is a national obsession, and so is our guilt over it. Pick up a magazine or listen to the punch lines of talk show comedians, and you are left with the notion that America’s conscience is concerned chiefly with diet and weight. And with some reason: One in three adults is overweight, up from one in four during the 1970s. And one in five teenagers—up from fewer than one in seven—is overweight or close to becoming overweight, according to a survey conducted by the Centers for Disease Control between 1988 and 1991.

At the same time, it is estimated that one in twelve American children suffers from hunger. So while we will focus here on avoiding the health problems brought on by eating too much and exercising too little, let’s not forget those among us who have too little on the table to begin with. It is critical that we continue to give nutritional assistance, especially to pregnant women, infants, toddlers, and schoolchildren, through government programs like WIC, food stamps, and school lunches.

I GREW UP in the “clean plate” era. Today I look back at my family table, circa 1959—the pot roast and potatoes piled high and spilling over the edges of our plates—and see a catastrophe of calories, whose consequences my brothers and I avoided during childhood by walking or biking back and forth to school and around town and playing hours and hours of sports. We were expected to eat all of whatever we were served. If we balked, we heard, like a broken record, stories about starving children in faraway lands who would gladly eat what we scorned. My brother Hugh became a champion cheek-stuffer. Tony offered to mail his food to any country my father named. In the end, we ate whatever we had to in order to be “excused” from the table.

As with so many other aspects of family life in recent decades, the pendulum has swung to the other extreme—in this case, from the “clean plate” theory of nutrition to the “no plate” one. Many families rarely sit down to even one daily meal together at a table in their home. It’s easier to grab a doughnut on the run in the morning, a burger and fries at lunch, and then for dinner to graze on takeout, with one eye on the TV.

The majority of adults and teenagers, who do not drink excessively or smoke, can go a long way toward safeguarding their long-term health through diet and physical activity. As Dr. C. Everett Koop, the former surgeon general, has said, “If we could motivate the public to focus on achievable and maintainable weight, we would have taken a very significant step toward preventing one of the most common causes of death and disability in the United States today.”

It is far easier to begin good nutrition in childhood, when parents largely determine their children’s diet and the eating habits of a lifetime are established. It’s important, however, that diet not become a household mania. Every parent knows that children go through “eating phases,” which they will outgrow and the rest of us must endure. When Chelsea was in preschool, there were a few weeks when she would not eat anything for lunch but green grapes and a grape jelly sandwich on white bread. After a few days of observing her class, a worker from the state’s child care licensing division asked the head teacher why the parents of the curly-haired blond girl sent her to school every day with such an inadequate lunch. The teacher refrained, thankfully, from naming the parents and assured her that she would talk to them.

Most of us are more relaxed than our parents were about exactly what our kids eat and how much, but a greater leniency should not become an excuse for poor nutrition. Despite—or maybe because of—all the nutrition information bombarding people every day, there is a lot of confusion about what to feed ourselves, let alone our kids. Even in the face of good information, we may be resistant to change. Head Start teachers have told me that after they’d taught children about healthy foods, some parents complained that they couldn’t afford the foods their kids requested or that they just didn’t “eat that stuff” in their house.

Good nutrition does not have to be expensive. As part of the Shape Up America! program he started, Dr. Koop recommends making healthy eating a permanent part of a family’s way of life, not an occasional “diet.” There has been a revolution in the past decade when it comes to information about food, and many of us now grasp the basics: we should be eating more grains, beans, fish, fruits, and vegetables and less meat, fat, and sugar. We should encourage our families to fill their plates with a moderate amount of food—a sensible meat serving, for example, is about the size of a deck of cards—and to refrain from seconds. New nutrition labels help us choose lower-fat milk and cheese and select other products that are lower in fat as well as higher in fiber. Many restaurants offer healthier alternatives—lean or “spa” cuisine.

We need to teach children to take responsibility for their own weight, rather than passing the buck to genetics or a slow metabolism. Although diet is not an exact science, and we differ in the amounts and kinds of foods we can healthily consume, these physiological factors account for only a small number of overweight people. Most of us (including me) simply exercise too little and eat too much.

If your children need to lose weight, help them to set a reasonable goal and make a sensible plan for getting there. Parents of teenage girls, who often believe they are overweight even when they are not, should take particular care to prevent their daughters from dieting excessively or obsessing about their weight. As Richard Troiano, one of the epidemiologists who conducted the Centers for Disease Control survey, reminds us, “There is already too much of a culture of thinness leading to eating disorders in this age group.” Their risk of nutritional deficiencies is serious.

I have read advice like Dr. Koop’s a thousand times and know that I could do better in my own eating. Since moving into the White House, I have enlisted the ingenuity of chef Walter Scheib in concocting menus for official events and family meals that live up to nutritional guidelines as well as the expectations visitors have for presidential hospitality. For family meals, we moved a table into the second-floor serving kitchen, where we usually (but not always!) dine on vegetables, grains, fruits, lean meats, and fish.

Diet alone does not account for the dramatic increase in weight among Americans, however, especially among children and teenagers. The main culprit is a combination of poor food choices and too little exercise. In many American households, the juvenile couch potato whose only operating muscles appear to be in his jaws, chomping away hour after hour on high-calorie nonfoods, is a familiar sight. A study by the Centers for Disease Control confirmed this picture, showing that physical activity among children and teenagers has declined during the time average weight has gone up.

In a 1990 Youth Risk Behavior Study, only 37 percent of high school students reported getting at least twenty minutes of vigorous exercise three or more times a week, down from more than 60 percent in the 1970s. My home state of Illinois is the last to mandate daily physical education for all students, kindergarten through twelfth grade, although the Illinois legislature recently passed a law allowing local school districts to apply for waivers. In most states, requirements are already left up to local school districts, and the results are not encouraging. Only half of American teenagers are enrolled in physical education classes, and only one in five attend daily. More than one in three, however, report watching three or more hours of television or videos every school day.

I was not always happy to have to take physical education classes every day of my school life, especially when I had to rush to my next class, my hair still dripping from the heavily chlorinated old pool. But I am grateful in retrospect that I learned about different sports, developed some athletic skills, and, most important, exercised my body as well as my mind each day.

I regret the move away from organized physical education and the reduction of recess time for younger kids. All children, especially in today’s stressful world, need the joyful release of free play as well as healthful exercise. Mens sana in corpore sano, the ancients advised, and it still holds true—a strong mind in a strong body.

How can we achieve that for our children? For starters, turn off the TV, VCR, and computer, get up, and get moving—and get your kids to do the same. Brisk walking, hiking, and bicycling are all good exercise and are great ways to spend time together as well. Put physical education and recess back into the school day. Thirty minutes a day of exercise is recommended for adults or children of average weight, forty-five minutes for overweight people, but it doesn’t have to be all at once. You can build shorter periods into your and your kids’ regular daily routines. Walk them to the park, school, or store instead of jumping in the car to go two blocks. Take the stairs instead of the elevator. Try to plan vacations and outings around exercise—nature walks, hiking trips, or camping and canoeing in our national parks.

The knowledge that poor nutrition and inactivity are clearly implicated in the high incidence of arthritis and such serious and often fatal illnesses as cancer, heart disease, and diabetes should be enough to get us and our children to shut the refrigerator door and open the front door.

The village can do its part to help. The U.S. Department of Agriculture, which oversees school lunch and breakfast programs, has started Team Nutrition, a partnership between the federal government, states, school districts, farmers, and businesses to promote healthy food choices in homes and schools and in the media. Among other projects, Team Nutrition has recruited volunteer chefs from leading restaurants to concoct recipes for nutritious cafeteria food—lemon chicken, vegetable lasagna, oranges and strawberries in tangerine juice—that kids actually will eat. I tried some rice pilaf with lentils, beans, and chick peas with a group of fifth and sixth graders, who not only ate what was served but said they liked it.

The President’s Council on Physical Fitness and Sports is working hard to convince schools both to require physical education for all grades and to give younger students opportunities during the school day to play outside in safe, supervised settings. The goal is to get at least half of all schoolchildren participating in daily physical education. The council emphasizes that classes should include more activities that people can readily pursue over a lifetime, like swimming, bicycling, jogging, and racquet sports.

It also recommends that communities increase the availability and accessibility of facilities for these and other activities. Many churches, like my husband’s, Immanuel Baptist in Little Rock, have built family centers that include athletic facilities for exercise classes, basketball games, and jogging or walking. But community recreation centers, especially for teenagers, are nonexistent in many neighborhoods where kids need them most. I can’t understand the political opposition to programs like “midnight” basketball and other recreational activities. Providing funds to inner-city neighborhoods to give young people positive outlets for their energies under adult supervision sounds great to me, as a way not only to prevent health problems but to prevent kids from getting into trouble.

KEEPING CHILDREN healthy in body and mind is the family’s and the village’s first obligation. But we all know that no matter how conscientious a parent might be or how committed to preventive health a community might be, children will inevitably suffer from disease and injury. Then medical care is required.

Three tales of our era:

A Texas teenager suffered from high blood pressure and recurring stomach pain, but he was uninsured and his family could not afford the tests that would determine the cause of his problems. Then he developed difficulty raising his arms as well. When he needed immediate medical care, he went to the emergency room of the local hospital. His mother applied for Medicaid but was told that the family’s income slightly exceeded the state’s eligibility level.

A six-year-old Kansas girl developed a severe infection that required mastoid surgery. When she was released from the hospital, physicians prescribed antibiotics to be administered by IV at home, but the family’s insurance policy refused to cover the cost. Without the antibiotics, she developed seizures and inflammation of the brain, and ultimately lost many fine motor and cognitive skills, including the ability to speak. She now requires complicated therapy and nursing care to manage her condition.

A Virginia woman was unable to afford health insurance for her son, who suffered from severe asthma. When he had an asthma attack, she would take him to the emergency room, where doctors would treat him and prescribe medication for him to continue at home. But his mother could not afford to have the prescriptions filled, and even when the doctors gave her a free dose to take home she held off giving it to him until the last possible minute, knowing she could not afford more.

I could tell you many other stories that end in the same question: Is this the kind of health care system our children deserve?

Today there are more than ten million children, most with working parents, who do not have health insurance; that number has been rising by about a half million a year. The rate will accelerate even more if Congress’s proposed cutbacks in Medicaid, which provides government insurance for poor children, are enacted. That would channel even more children into overworked emergency rooms for basic care, where overworked staffs will eventually be forced to turn them away.

When I look into the eyes of parents whose children’s illnesses are not only taking an emotional toll but exacting a cruel financial cost because they could not afford insurance, I think, There but for the grace of God go I and everyone I love. The number of Americans who will face these heartbreaks is growing.

Some families who can afford to pay for private insurance are unable to find coverage. In Cleveland, Ohio, I met a couple who have two daughters with cystic fibrosis and a healthy older son. The father, a self-employed professional, provided health insurance to his employees and their families. The family could afford private insurance for themselves and their son and would have bought it for their daughters but could find no one willing to sell them a policy because of the girls’ conditions. They repeated to me the words of one insurance agent—words I will never forget as long as I live. “What you don’t understand,” the agent told them, “is that we don’t insure burning houses.”

I find this attitude deplorable. What kind of message does it send to hardworking people who love their children but cannot protect them? And if we are willing to write off these children, whose will be next? That is a question for all of us to ponder, because as research in genetics continues to advance, scientists will soon be able to tell us which of our genes predispose us to cancer or diabetes or many other serious diseases. Will those of us who carry such genes and the children we pass them on to eventually be denied insurance too?

When I met seven-year-old Ryan Moore of South Sioux City, Nebraska, I knew I had encountered a young person of heroic disposition. Ryan was born with a congenital syndrome that produces multiple birth defects. His father, Brian, was able to provide his family with good health insurance until Ryan was a year old, when the company Brian worked for went out of business. Brian searched for work but was unable to find a job because companies were wary of his son’s health care needs. “It’s like they looked right through me and only saw my son,” said Brian. “I have a lot to contribute, and I couldn’t even get work as a janitor.”

Seven-year-old Ryan, however, did find work. He has become a local celebrity, mainly by being himself—hopeful, happy, and resilient in the midst of all his troubles. Ryan has been working with the Children’s Miracle Network and raising money to support his high medical and travel costs. This brave little boy loves to quote Piglet from Winnie-the-Pooh: “It is hard to be brave when you are such a small animal.”

Another small, brave soul I met was four-year-old Mike Bebout, who came to the White House for a children’s health event. He has suffered all his life from short bowel syndrome, which prevents his body from absorbing the nutrients it needs. His parents could not get private insurance to cover his treatments. His older brother, another Ryan, told me that he thought every kid should get the health care he needs, and he had come up with an acronym for the cause—MIKE—Medical Insurance for Kids Everywhere.

The lack of adequate health care for many Americans forces us into an emergency situation on every level. People use emergency wards as clinics, overburdening hospitals’ resources and often receiving, in turn, inadequate preventive or follow-up care. Infants and children end up with serious conditions requiring expensive care because we don’t invest in prevention. Toddlers don’t get their immunizations on time. School-age children don’t get the nourishment or exercise they need to feed their growing minds and bodies.

Many people believe that we cannot guarantee health care to all because of cost. In fact, a sensible universal system would, as in other countries, end up costing us less. That’s because most children who become ill or injured are eventually treated somewhere, even if they are given too little, too late, and at a greater cost than they—or we—would have paid if we had made sure their symptoms had been treated earlier. But until we are willing to take a long, hard look at our health care system and commit ourselves to making affordable care available to every American, the village will continue to burn, house by house.

You can already get a good look at the fallout from our procrastination by visiting the emergency room of any large urban hospital. On display are not just the medical crises for which an emergency room is designed but dozens of children, from infants to teenagers, who don’t appear to have any serious ailment. Why are they there? They have fever, earaches, stomach upsets—the kinds of aches and pains that are better treated by a school nurse or at a doctor’s office or clinic, or, better yet, warded off with good preventive care.

But most schools no longer have nurses, and doctors cost money—and even people with insurance find that many policies do not cover routine preventive services for children. Most public health clinics are not open at hours that are convenient for working parents. The for-profit clinics sprouting up in shopping malls keep longer hours but require cash or verifiable credit and are not always easily accessible.

If the number of uninsured Americans continues to rise and the influence of profit-driven medicine continues to grow, many nonprofit hospitals will be forced to close, and ultimately those who cannot afford the cost of expert care will be forced to fall back on low-tech, hands-on solutions. Ironically, less developed nations will be our best models for the home doctoring we will then need to master. If this scenario sounds farfetched, let me tell you that it is already happening. When I visited the International Center for Diarrheal Disease Research in Bangladesh, funded in part with American aid, I met a doctor from Louisiana who was there to learn about low-cost techniques he could use back home to treat some of his state’s more than 240,000 uninsured children.

I started this chapter with Dr. Lowe’s prescription, and like all the remedies she’s ever prescribed for my child, I’ve found it sound: Commonsense prevention in our homes and schools. A reformed health care system that guarantees all children the medical care they need. Money would be saved from both these approaches instead of the billions of dollars we now spend to fix problems we could have avoided in the first place.

I’m not sure we will follow Dr. Lowe’s prescription in the short run, but I know we will eventually. One of the reasons I worked so hard on health care reform was that I could not stand the fact that there are millions of children who do not have health insurance and millions more who are dependent on Medicaid, which may not be as available in the future if the current Congress gets its way. Our society will not be able to afford the moral or economic costs of intensively caring for children who should have been, in Dr. Lowe’s words, “treated right in the first place.”