Children Are Born Believers

Every child comes with the message that God is not yet

discouraged with Mankind.

RABINDRANATH TAGORE

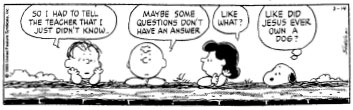

Some of the best theologians I have ever met were five-year-olds.

As children, my friends and I had long, serious discussions about what heaven would be like. One day a boy named David, who had bright-red hair and freckles, announced that he wouldn’t go to heaven if he couldn’t have peanut butter. We all argued over whether angels (which we all hoped to become) ever ate anything, let alone peanut butter. As the debate raged on, each of us sought guidance from a higher authority—our parents. When we compared answers the next day, we found that grown-ups could not agree on this critical theological point, either.

I sympathized with our parents years later, when Chelsea and her friends came to Bill and me with even weightier inquiries. By first grade, they were asking: “Where is heaven, and who gets to go there?” “Does God ever make a mistake?” “What does God look like?” “Why does God let people do bad things?” “Do angels have real bodies?” “Does God care if I squash a bug?” “Is the Devil a person inside or outside of us?”

Bill and I were struck by these questions, even as we struggled to provide thoughtful answers within the scope of a child’s understanding. They reflected a much deeper spirituality than we generally give children credit for. And they strengthened my belief that children are born with the capacity for faith, hope, and love, and with a deep intuition into God’s creative, intelligent, and unifying force. As child psychiatrist Robert Coles observes in his book The Spiritual Life of Children, “How young we are when we start wondering about it all, the nature of the journey and of the final destination.”

PEANUTS® reprinted by permission of United Feature Syndicate, Inc.

Like the potential to walk or to read, the potential for spirituality seems to be there from the beginning. A wonderful little book, Children’s Letters to God, contains messages that are filled with hope and trust, humor and sensitivity, and an awesome sense of familiarity. “Dear God,” writes one young child, “I bet it is very hard for you to love all of everybody in the whole world. There are only four people in our family, and I can never do it.” Another asks, “How did you know you were God?”

The inclination toward spirituality does not need to be planted in children, but it does need to be nurtured and encouraged to bloom. One way we do this is by teaching children to translate the spiritual impulse into the shared form of expression, in words and rituals, that religion provides.

Religion figures in my earliest memories of my family. My father came from a long line of Methodists, while my mother, who had not been raised in any church, taught Sunday school. During a recent visit, she joked that she had begun doing so in order to keep Hugh from sneaking out of his class. When a friend of mine asked her what the essence of her spiritual teaching was, she replied, simply and sincerely, “A sense of the good.”

We attended a big church with an active congregation, the First United Methodist Church in Park Ridge. The church was a center for preaching and practicing the social gospel, so important to our Methodist traditions. Our spiritual life as a family was spirited and constant. We talked with God, walked with God, ate, studied, and argued with God. Each night, we knelt by our beds to pray before we went to sleep. We said grace at dinner, thanking God for all the blessings bestowed. My brother Hugh had his own characteristic renditions, along the lines of “Good food, good meat, good God, let’s eat!” But despite our occasional irreverence, God was always present to us, a much-esteemed, much-addressed member of the family.

Bill is a Southern Baptist who feels as close to his denomination as I do to mine. Over the years, we have attended each other’s churches often, and Chelsea spent time in both until she was ready to decide, at age ten, to be confirmed as a Methodist. The particular choice was not as important to her father and me as was her commitment to being part of the fellowship and framework for spiritual development that church offers.

The anthropologist Margaret Mead felt that exposure to religion in childhood was important, because prayer and wonder are not so easy to learn in adulthood. She was also concerned that adults who had lacked spiritual models in childhood might be vulnerable as adults to the appeals of intolerant or unduly rigid belief. My own experiences confirm Mead’s conviction. I have known parents who were not themselves religious but who conscientiously ensured that their children were exposed to at least one religious faith for these reasons. I have also met people who had turned away from the teachings or structure of the faith in which they had been raised but were inspired to return by their own children.

At a formal dinner recently, I sat next to a distinguished businessman who told me he had started reading the Hebrew Bible from the beginning. Even though he had been bar mitzvahed decades before, he had not thought of himself as a religious or spiritual man. But one day, while holding his daughter, he had pointed at the sunset and said, “Look at the beautiful painting God gave us tonight.” His little girl asked, “Who is God?” He decided that he owed it to her to introduce her to religious faith, just as his parents had introduced him. There is no substitute for this. If more parents introduced their children to faith and prayer at home, whether or not they participated in organized religious activity, I am sure there would be fewer calls for prayer in schools.

CHURCHES, SYNAGOGUES, mosques, and other religious institutions not only give children a grounding in spiritual matters but offer them experience in leadership and service roles where they can learn valuable social skills. A friend, reflecting on the role of formal religion in her childhood, remarked one day, “My church was my finishing school.” She recalled the first time she spoke in public, a one-line recitation as part of an Easter morning program when she was four. Each successive Easter, her part in the program grew larger. Her church leader showed her how to speak clearly and loudly. With every public performance, she gained greater self-confidence.

I knew what she meant. In my own church, I took my turn at cleaning the altar on Saturdays and reading Scripture lessons on Sundays. I participated in the Christmas and Easter pageants (learning a lesson in recovering poise the time I fainted in my angel costume in the overheated sanctuary) and read my confirmation essay on “What Jesus Means to Me” before the whole congregation.

Chelsea’s Sunday school teachers in Little Rock and Washington have helped her and her peers to explore and express ideas, worries, and fears, from getting along with parents who “just don’t understand” to dealing with teenage temptations. Churches are among the few places in the village where today’s teenagers can let down their guard and let off steam among adults who care about them. Churches that make kids feel welcome and supported are doing more than involving them in worship. As I have mentioned, a survey of teenagers’ attitudes and behaviors found that those who attend religious services regularly are less likely to experiment with risky behaviors like drug use. I wish more places of worship were open after school and on weekends to provide constructive activities for kids under adult supervision.

Some churches are becoming villages in themselves, offering members access to state-of-the-art technology, family centers, and adult discussion groups on topics like marriage and parenting. Many churches, like mine in Little Rock, offer preschool and day care programs, and some now include athletic facilities and even restaurants. These churches provide a social center for people of all ages.

But no matter how broadly churches and other places of worship are redefining and expanding their religious and social roles, the right to religious and spiritual expression extends beyond their boundaries. How do we protect that expression under the First Amendment’s guarantee of freedom of religion and its prohibition against any government “establishment” of religion? For children, this question often concerns the extent to which they may learn about religion and express their own religious convictions in our public schools. I share my husband’s belief that “nothing in the First Amendment converts our public schools into religion-free zones, or requires all religious expression to be left behind at the schoolhouse door,” and that indeed “religion is too important in our history and our heritage for us to keep it out of our schools.”

On the other hand, we run into problems when people want to use governmental authority to promote school prayer or particular religious observances or to advocate sectarian religious beliefs. When public power is put behind specific religious views or expressions, it might infringe upon the companion freedom the First Amendment guarantees us to choose our own religious beliefs, including the right to choose to be nonreligious.

To bring reason and clarity to this often contentious issue, my husband asked Secretary of Education Richard Riley and Attorney General Janet Reno to develop a statement of principles concerning permissible religious activities in the public schools. The complete guidelines, which are available at your local school district office or the Department of Education, include the following:

- Students may participate in individual or group prayer during the school day, as long as they do so in a non-disruptive manner and when they are not engaged in school activities or instruction.

- Schools that generally open their facilities to extracurricular student groups should also make them available to student religious organizations on the same terms.

- Students should be free to express their beliefs about religion in school assignments, and their work should be judged by ordinary academic standards of substance and relevance.

- Schools may not provide religious instruction, but they may teach about the Bible or other scripture (in the teaching of history or literature, for example). They may also teach civic values and virtue, and the moral code that binds us together as a community, so long as they remain neutral with respect to the promotion of any particular religion.

This last point is particularly important, because it defines an area in which the role of religious institutions overlaps with the role of parents, schools, and the rest of the village: the responsibility of helping children to develop moral values, a social conscience, and the skills to deal with the issues they will confront in the larger world. Just as it is appropriate, often necessary, for schools and other institutions to help build character by teaching the values at the heart of religious creeds, it is also necessary for churches to connect the development of personal character to life in the world beyond home and church.

My church took seriously its responsibility to build a connection between religious faith and the greater good of a society full of all kinds of people. I received my earliest lessons about how we were expected to treat other people by singing songs like “Jesus loves the little children / All the little children of the world / Red and yellow, black and white / They are precious in His sight.” Those words stayed with me longer than many earnest lectures about race relations. (To this day I wonder how anyone who ever sang them could dislike someone solely for the color of his skin.)

My church’s youth minister, the Reverend Donald Jones, arranged for my youth group to share worship and service projects with black and Hispanic teenagers in Chicago. We discussed civil rights and other controversial issues of the day, sometimes to the discomfort of certain adults in the congregation. Reverend Jones took a group of us to hear Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., speak at Orchestra Hall (despite some church members’ suspicion that King was a Communist). We argued over the meaning of war to a Christian after seeing for the first time works of art like Picasso’s Guernica, and the words of poets like T. S. Eliot and e. e. cummings inspired us to debate other moral issues.

I wish more churches—and parents—took seriously the teachings of every major religion that we treat one another as each of us would want to be treated. If that happened, we could make significant inroads on the social problems we confront.

Many parents do make the teaching of these values an essential component of religious instruction, and many others see them as a focus in themselves. Like me, however, they have undoubtedly learned to recognize the look of young eyes glazing over at the first hint of a long-winded explanation of some principle. Better a story that demonstrates the spiritual and human qualities we wish to transmit to young people. In our bedtime reading and prayer ritual when Chelsea was younger, Bill and I read children’s versions of Bible stories to her. Cain and Abel exemplified envy and its consequences. David’s conflict with Goliath illustrated the power of faith in the face of overwhelming odds. Queen Esther’s courage in saving the Jews underscored the need for courage and careful planning before taking risky action. The Good Samaritan parable is an example of compassion toward people who are of different backgrounds. Religion is not just about one’s relationship with God, but about what values flow out of that relationship, how we follow them in our daily lives and especially in our treatment of our neighbors next door and all over the world.

Stories about contemporary or historical figures can also make the point about the power of faith to give courage. One of my heroes when I was growing up was Margaret Chase Smith, the first woman elected to both the U.S. House of Representatives and the Senate. I admired her courage in standing up to her fellow Republican Senator Joe McCarthy and his political smear tactics. In her essay “This I Believe,” she explained the core of her courage. “I believe that in our constant search for security we can never gain any peace of mind until we secure our own soul. And this I do believe above all, especially in my times of greater discouragement, that I must believe—that I must believe in my fellow men—that I must believe in myself—that I must believe in God—if life is to have any meaning.” I would add to Senator Smith’s eloquent statement of her belief that she translated it into action, and so must we if our convictions are to have meaning beyond ourselves.

Preaching is a distant second to practicing when it comes to instilling values like compassion, courage, faith, fellowship, forgiveness, love, peace, hope, wisdom, prayer, and humility. By putting spiritual values in action, adults show children that they are not just for church or home but are to be brought into the world, used to make the village a better place. It is not always easy to live what we believe, however. For example, while I believe there is no greater gift that God has given any of us than to be loved and to love, I find it difficult to love people who clearly don’t love me. I wrestle nearly every day with the biblical admonition to forgive and love my enemies.

THE STRUGGLE to live up to the spiritual values we profess is not only an individual one. Groups of people, even nations, can suffer from an absence or misuse of spirituality. The great physician and philosopher Albert Schweitzer likened the condition of the soul in modern life to sleeping sickness. He warned against the indifference and apathy that can overtake our lives in the absence of love for one another and for God.

For the United States, that same warning was sounded by Lee Atwater, one of the political strategists credited with the victories of Ronald Reagan and George Bush. When Atwater was dying, he told a Life magazine reporter: “Long before I was struck with cancer, I felt something stirring in American society. It was a sense among the people of the country, Republicans and Democrats alike, that something was missing from their lives, something crucial…. I don’t know who will lead us through the ’90s, but they must be made to speak to this spiritual vacuum at the heart of American society, this tumor of the soul.”

I cut out that passage and put it in a little book of sayings and Scriptures that I keep. And I think the answer to his question—“Who will lead us out of this spiritual vacuum?”—must be all of us. Not just our government, not just our institutions, not just our leaders and preachers and rabbis, but all of us must renew our own sense of spirituality and work to live up to its expectations and values.

As we engage in that renewal, though, we have to beware of the misuse of religion to further political, personal, even commercial agendas. If we employ it as an excuse for intolerance, divisiveness, or violence, we betray its purpose, as did the extremists who employed religious rhetoric to justify assassinating Prime Minister Rabin of Israel. The “true believer” who proclaims that God or the Gospel or the Torah or the Koran favors a particular political action and that anyone who opposes him is on the side of the Devil is asserting an absolutist position that permits no compromise, no deference to the will of the majority, no acceptance of decisions by those in authority—all necessities for the functioning of any democracy.

Religion is about God’s truth, but none of us can grasp that truth absolutely, because of our own imperfections and limitations. We are only children of God, not God. Therefore, we must not attempt to fit God into little boxes, claiming that He supports this or that political position. This is not only bad theology; it marginalizes God. As Abraham Lincoln said, “The Almighty has His own purposes.” Even in dealing with political issues that have serious moral implications, we must be careful to avoid demonizing those who disagree with us, or acting as if we have a monopoly on truth.

People of faith belong to the larger village along with other citizens, the majority of whom share many—but not all—of their values. Our laws are designed to permit us to live in harmony, even when we have serious differences over religious and political matters. But to achieve that harmony, more than law is required; mutual tolerance and respect are also necessary.

I have been privileged to meet some of our world’s great religious leaders, among them Roman Catholic, Protestant, and Orthodox Christians, Jews, Muslims, and Buddhists. Despite their profound differences, each speaks from a deep wellspring of love that affirms life and yearns for men and women to open their hearts like children to God and one another. Indeed, given the spiritual inclination of children, it is fitting that in many religious traditions they lead the way to spiritual awareness and enlightenment. As the Bible says, “And a little child shall lead them.” When we find ourselves growing impatient, ungrateful, or intolerant, children can remind us to appreciate our daily blessings, to practice kindness, even to love our enemies. As children’s spirituality blossoms, it will—if we let it—open in the hearts of adults a greater capacity to care for all children, to take responsibility for them and to pray for their futures. And when we pray for others, we often find in ourselves the energy to put ourselves to work on their behalf.

At the same time, prayer allows us to let go of our children and to let them find their own ways, with faith to guide and sustain them against the cruelties and indifference of the world. In her book of prayer, Guide My Feet, Marian Wright Edelman looks back upon a childhood that was a marvelous mixture of spiritual joy and exuberant, though disciplined, family and communal life. She writes: “We black children were wrapped up and rocked in a cradle of faith, song, prayer, ritual, and worship which immunized our spirits against some of the meanness and unfairness…in our segregated South and acquiescent nation.” I have seen that immunity at work in my own life and the lives of others. But someone must inoculate each new generation, and then administer “booster shots” through example and ritual.

In the first part of her autobiography, I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings, Maya Angelou recounts the rape she experienced as a child, which left her mute for several years. Her life today represents a triumph of spirit that she attributes in part to the deep spirituality she developed as a traumatized child. “Of all the needs…a lonely child has, the one that must be satisfied, if there is going to be a hope of wholeness, is the unshaking need for an unshakable God.” Amen.